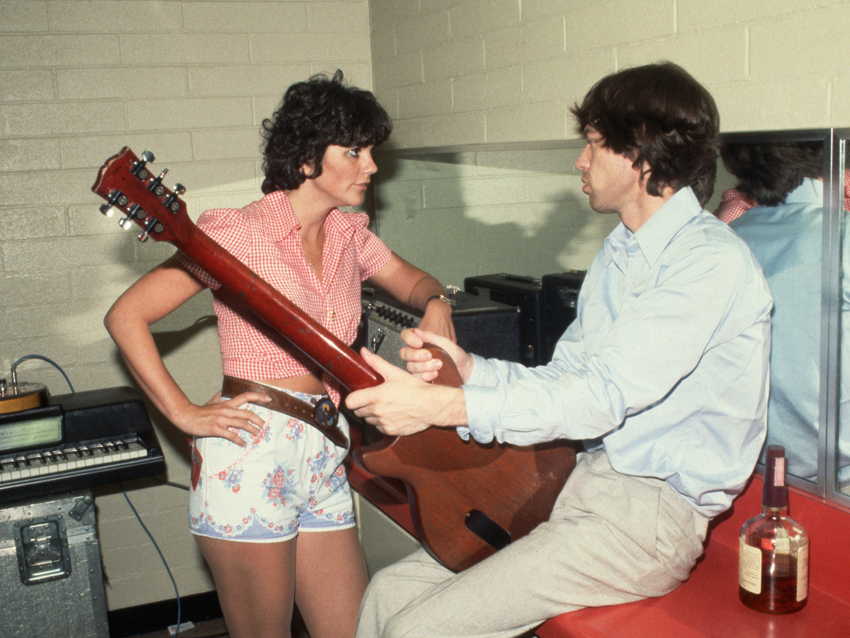

Linda Ronstadt talks '70s songwriters, her career and memoir, Simple Dreams

“I don’t think I was very good when I started out," says Linda Ronstadt with astonishing frankness. The legendary vocalist, whose catalogue of '70s recordings, an impeccable blend of country-tinged, R&B-flavored pop-rock that showcased such emerging songwriters as J.D. Souther, Warren Zevon, Don Henley and Glenn Frey, and caught the mainstream by the scruff of the neck, makes it clear that she is not one for self-serving hyperbole.

"I’ve never been happy with the quality of my work," she says. "I always felt as though my musicianship was lacking and that I should have worked harder at it when I was younger. As I sang and sang, I improved."

In Ronstadt's view, she started to find her true voice after 1980's new-wavish Mad Love and later that year when she tackled the demanding role of Mabel in Joseph Papp's production of The Pirates Of Penzance. She would continue to flex her vocal muscles on groundbreaking recordings that spanned every conceivable genre: the big band songbook of Nelson Riddle, traditional Mexican folk, jazz, Afro-Cuban, Cajun – nothing seemed outside her reach.

Ronstadt traces her creative journey in exacting detail in a just-released book, Simple Dreams: A Musical Memoir, and much like the way she regards her recorded work, she says that the writing process was one of evolution and discovery. "I started writing, and I got better," she explains. "I’d never written before. I couldn’t even make an outline – I thought it was hopeless. So I started at the beginning, and because I knew what happened next, one thing led to the next. And I decided to focus on the music because that’s the only thing worth sharing, really.”

Ronstadt sat down with MusicRadar recently to talk about Simple Dreams and to share her reflections of music making in the '70s. Additionally, she discussed the state of her health – prior to the book's publication, she disclosed that she's been battling Parkinson's disease and has lost her ability to sing.

As you point out, you focused on the music in your book. But did you ever consider weaving more personal relationship stories into the narrative? Not the dirt per se, the usual sex and drugs thing…

“I just decided to write a book about the music, that’s all. To me, that’s the only thing that’s interesting. If people want that sort of thing, there’s other books out there [laughs]. My goal was to put down my musical observations. People have often written about me, that I did this for this reason and that for that reason, and they’re usually 98 percent wrong.

“The idea that I would make any of these decisions and make certain records as career moves is ridiculous. They were terrible career moves. [Laughs] But my manager and my record company, to their credit, helped me carry out my whims once they saw that I was determined to do it. The Mexican songs that I was getting and the American standards songs that I loved to sing were mostly better than what I was being offered in contemporary mainstream pop at the time.”

You established yourself early on as an interpreter of other people’s songs. Did you ever try to write more of your own material?

“Songwriting wasn’t my gift. I think you have to cultivate a gift; you have to practice and develop craft around your gift it so that you can execute it in more convenient, efficient ways. I just didn’t wake up and say, ‘I’ve got to write a song.’ Jackson Browne wakes up and writes a song down on a napkin – that was his gift. I used to live with J.D Souther, and I would watch him write. He’s be sitting, he’d say something, and then he’s write it down. That’s craft.”

Linda Ronstadt talks '70s songwriters, her career and memoir, Simple Dreams

The early to mid-‘70s was such a zeitgeist period for songwriters, many of whom you knew and worked with. What’s your take on songwriting these days?

“I think everybody finds their milieu – their buddies and their cronies and people with similar sensibilities. Talent never deserts the gene pool, not unless you get so much lead poisoning that you’re not able to act on it. Those people weren’t stars or part of a particular movement; they were just my pals, and they were writing good songs.

“Jimmy Webb is a master. He’d had success early on, and of course, writers like J.D. and Jackson and Don Henley all revered Jimmy. They thought he was ‘the guy’ – and he was. What a good writer.”

I’m curious – did LA in the ‘70s feel like a particularly creative time? I liken it a little to what was happening in England in the early ‘60s.

“No, not really. We knew who our peers were. The people who were at one side of the Troubadour, we were all kind of chasing country-rock. I wanted to do country songs with a rhythm and blues feel, and that was my idea to mix up rhythm and blues with a pedal steel guitar and a fiddle. My voice was suited for that; it’s not suited for short bursts of rock ‘n’ roll while you’re waiting for the lead guitar solo.

“A guy like Mick Jagger doesn’t need such a generous melody, because who cares what his voice sounds like? He’s a great communicator. He’s not a particularly good singer; he’s not a particularly good dancer, guitar player or musician; but he’s a sum of the parts, a dream maker.”

You did a pretty good job of singing Tumblin’ Dice yourself.

“Well, but it was a real underuse of my ability in terms of what I can do. You know, if you’re Waddy Wachtel, you wanna play Tumblin’ Dice because you can do a lot of posturing with your guitar. As a singer, there wasn’t much for me to do. It’s an interesting song, and I think it’s well written. I think that Mick and Keith are really clever. They’re excellent for that kind of thing, but it’s not a singer’s vehicle.”

Linda Ronstadt talks '70s songwriters, her career and memoir, Simple Dreams

Peter Asher was your producer and manager at the time. How did the two of you look for material? Did you have a particular process?

“Peter didn’t do it; I looked for material myself. Nobody chose songs for me except for me, not until I started working with Emmylou Harris, and then she would always bring a great song. And then when I worked with Ann Savoy, she would always bring great songs. But those two individuals were the exceptions of my career.”

What’s interesting is, the songwriters in the ‘70s wrote deeply personal songs that connected with a mass audience.

“I think it might be like the film business. Films that are written by the director have a more singular vision, instead of a corporate thing where the suits all get involved, and they grind what they can out of several writers. I don’t think that’s real healthy, although collaboration can be quite good.”

You mentioned Waddy Wachtel. You worked with the second coming of the "Wrecking Crew," if you will – guys like Waddy, Danny Kortchmar, Russ Kunkel –

“The Section, yeah, they were great. Danny Kortchmar, what a brilliant, brilliant guitar player. Every time I played with him, I got better. He played on Mad Love, and he did such wonderful work. My singing wasn’t quite there yet, but it was getting there. On that record, it was starting to move into another room.”

I’m glad you brought up the Mad Love album. I love that record, but I remember you getting a lot of flack for it at the time. It was your flirtation with new wave, which rubbed some people the wrong way.

“Again, it wasn’t any decision to be trendy; those were simply the songs that were being brought to me. I haven’t heard that record since I made it, but I do remember at the time that Danny’s work was stellar. I was also so happy with him on the road because we could play off of each other really well.”

There were three Elvis Costello songs on Mad Love. Obviously, you were responding to him as a songwriter.

“Well, sure – he’s a good songwriter. I looked for good writers. If I found a song with beautiful craft and it had something that I could do to it with my voice, I was gonna grab it. I didn’t care who wrote it.”

Linda Ronstadt talks '70s songwriters, her career and memoir, Simple Dreams

You recently disclosed that you have Parkinson’s Disease. How are you doing? Are you feeling OK?

“I’m doing fine. If I can wake up and walk and talk, I think that’s pretty good. I’ve given up on the idea that I’ll be able to sing again. I knew that something was wrong for years, and I didn’t know what it was, and I’ve been dealing with it for years. It’s not like the feeling is new; it’s just that the information that’s causing the feeling is new.”

When you say that you can’t sing anymore, do you mean to the ability you once had, or do you mean not at all?

“It means I can’t even sing Happy Birthday. If you ever look up anything about how vocal cord projection works, there’s an exquisite confluence of muscle repetitive movement and coordination that takes place, and it all happens unconsciously. To produce a note, you need that muscle agreement, and then, of course, you bring in your own colors and textures, and you try to phrase and make some sort of rhythm impulse. It’s really impossible for me to even produce a tone. I can’t even call my cat in the backyard.”

I’m sure you don’t want sympathy and people feeling sorry for you, but still, to hear all of this is heartbreaking.

“Well, I am 67 years old, and at that age, something’s gonna get you. We’re all going to die. I could get hit by a bus tomorrow, and then it wouldn’t be this. But like I said, I wake up, and if I can walk and talk, that’s pretty good. [Laughs] There will be a time when I won’t be able to, if I live that long.”

Congrats on the nomination to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. What are your feelings on the Rock Hall?

“It’s not an issue for me. I never felt defined by rock ‘n’ roll. Other people made it an issue – I never did. You don’t sing for prizes; you sing to process. Art is there to help us identify our feelings, to help us through our workday, to help us with a lot of things. I mean, nobody likes to work in a vacuum. It’s nice to have your work acknowledged, even if it’s in the room where you are. But it’s not necessary for the work.”

Linda Ronstadt talks '70s songwriters, her career and memoir, Simple Dreams

Of your classic hits, is there any one in particular that holds a special place in your heart?

“I don’t like any of them. It’s not that they’re bad songs – I chose them and did the best I could with them, but I don’t think I did very well. Before 1980, my phrasing just wasn’t very good. I started to do the Nelson Riddle stuff in particular to work on my phrasing; I think I succeeded to a degree.

“I wasn’t the world’s greatest phraser. I still wasn’t as good as Bonnie Raitt. I love Bonnie – she’s fabulous. I’m going to take her to lunch next week. I’m delighted that she can phrase better than I can. And same with Jennifer Warnes. I heard her sing at the Troubadour the same night I heard Bonnie. I had already heard Jennifer on the Smothers Brothers show, and we played together at a little beatnik dive called The Insomniac. I remember seeing her warm up outside, and I thought she was very dedicated. There are these people that make you go, ‘I’m never gonna be that good.’ But so what? You just do the best you can.”

Are there any current singers you like?

“Of course, there’s Adele. And there was Amy Winehouse, poor girl, who was better than any of us. There’s a singer I love from Spain named Estrella Morente She’s a very traditional flamenco singer, and she’s just fabulous – a very beautiful girl. I listen to her all the time now. And there’s a really good singer in Mexico City named Natalia Lafourcade. She’s very urban. I mean, there’s some really good people sticking their heads up out there. Like I said, talent never leaves the gene pool.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.