Leland Sklar on studio ethos, big gigs and working with music legends

In-depth with the legendary bearded bassist

Introduction

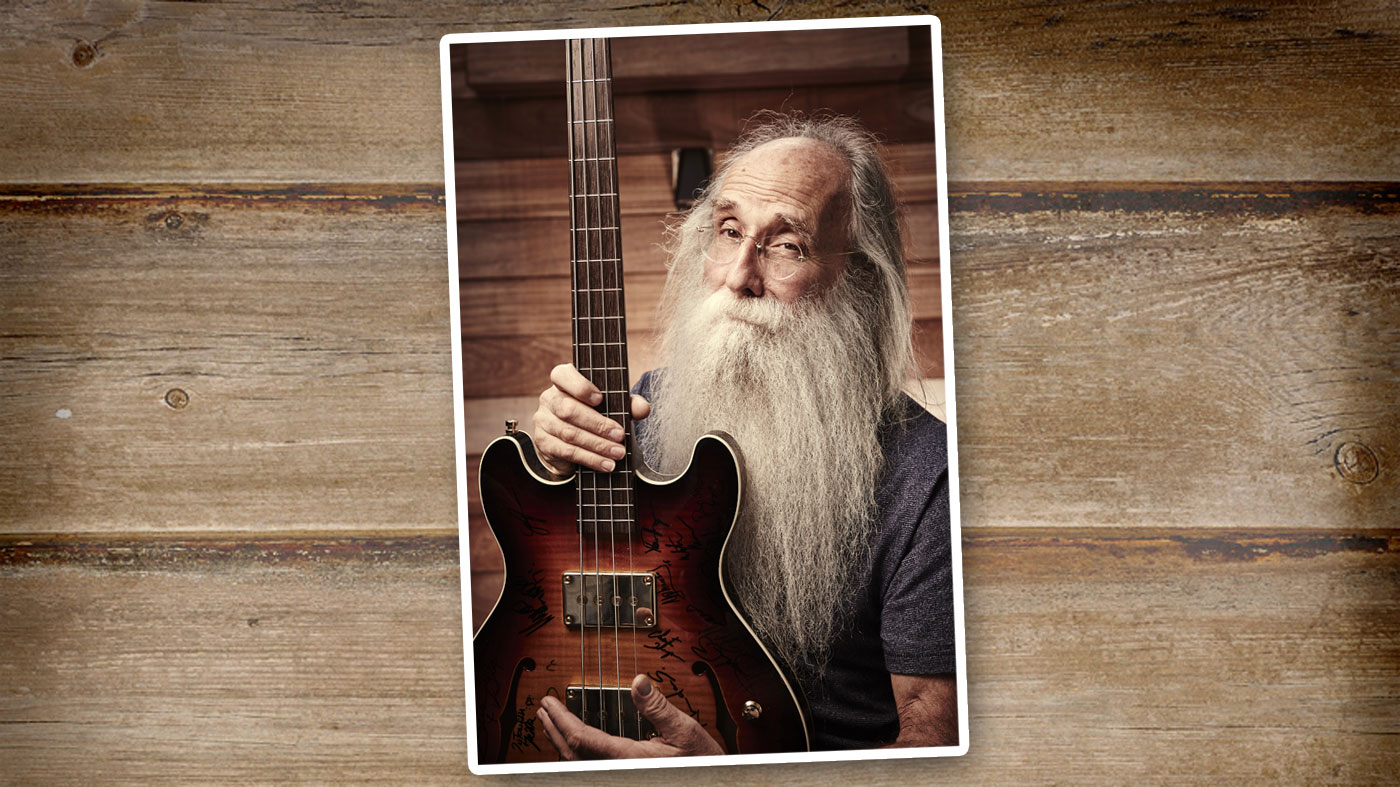

The list of hit albums he’s played on is even longer than his beard - but you won’t meet a more down-to-earth legend than session bass supremo Lee Sklar. Guitarists of the world take heed: Lee has some advice for you, and it works as well for six strings as four…

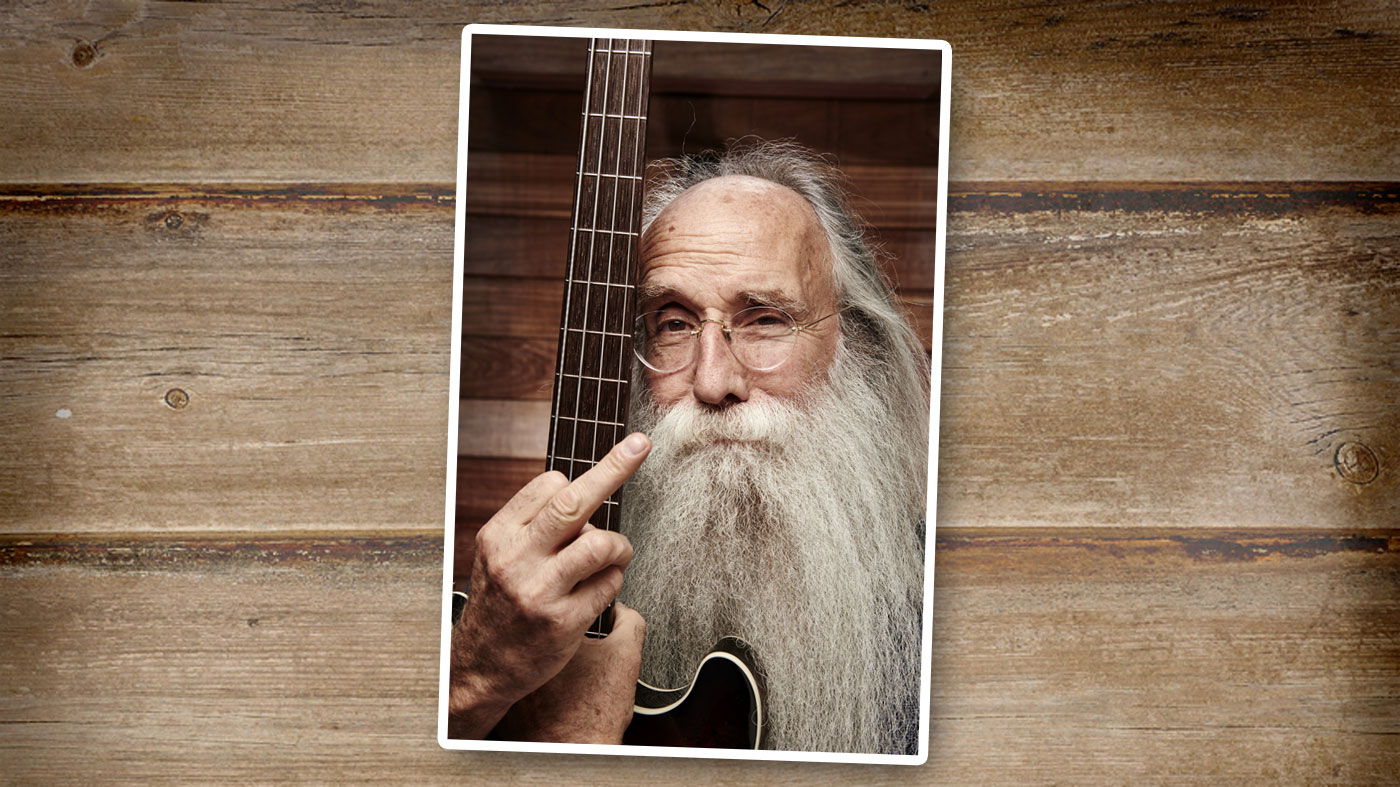

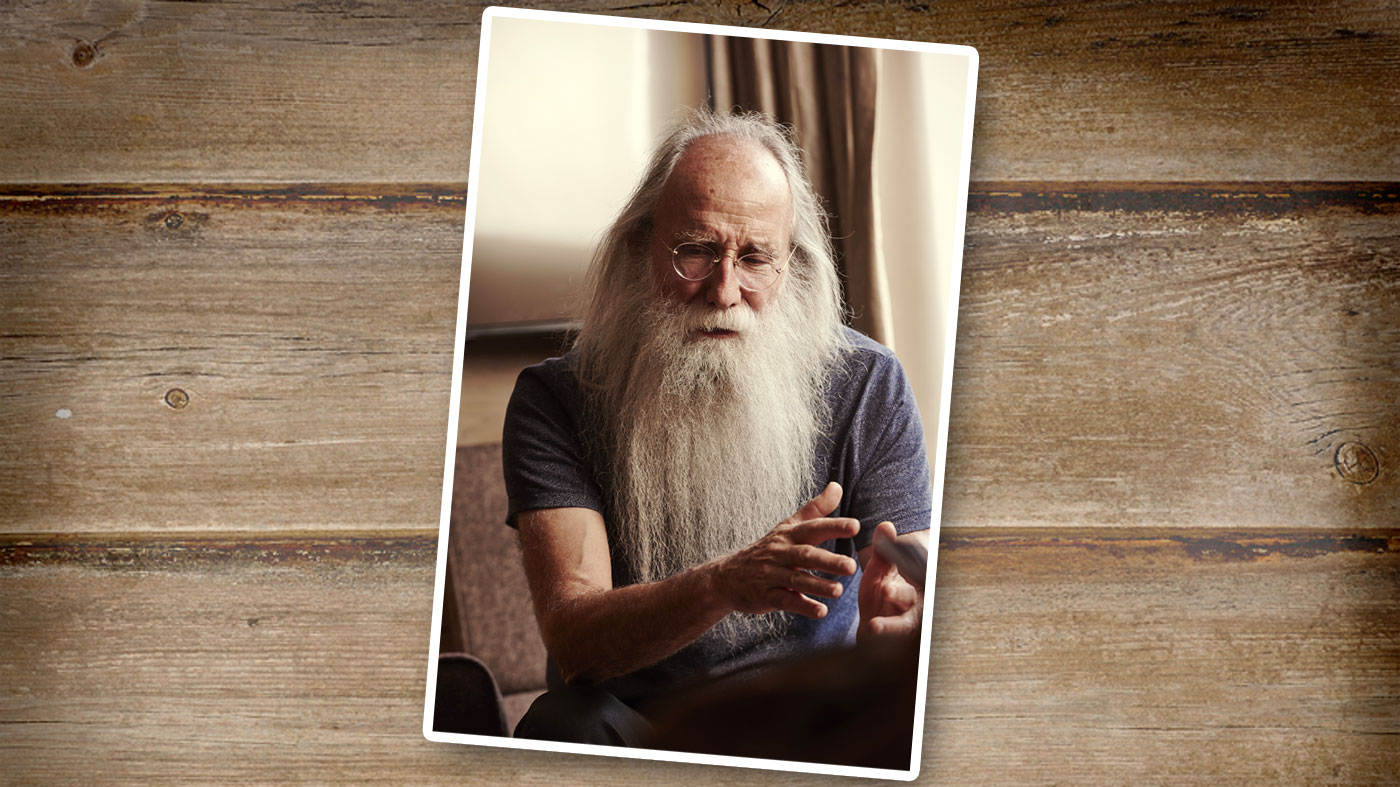

Despite his penchant for a ribald gesture, Lee’s one of the most intelligent, thoughtful commentators we’ve met

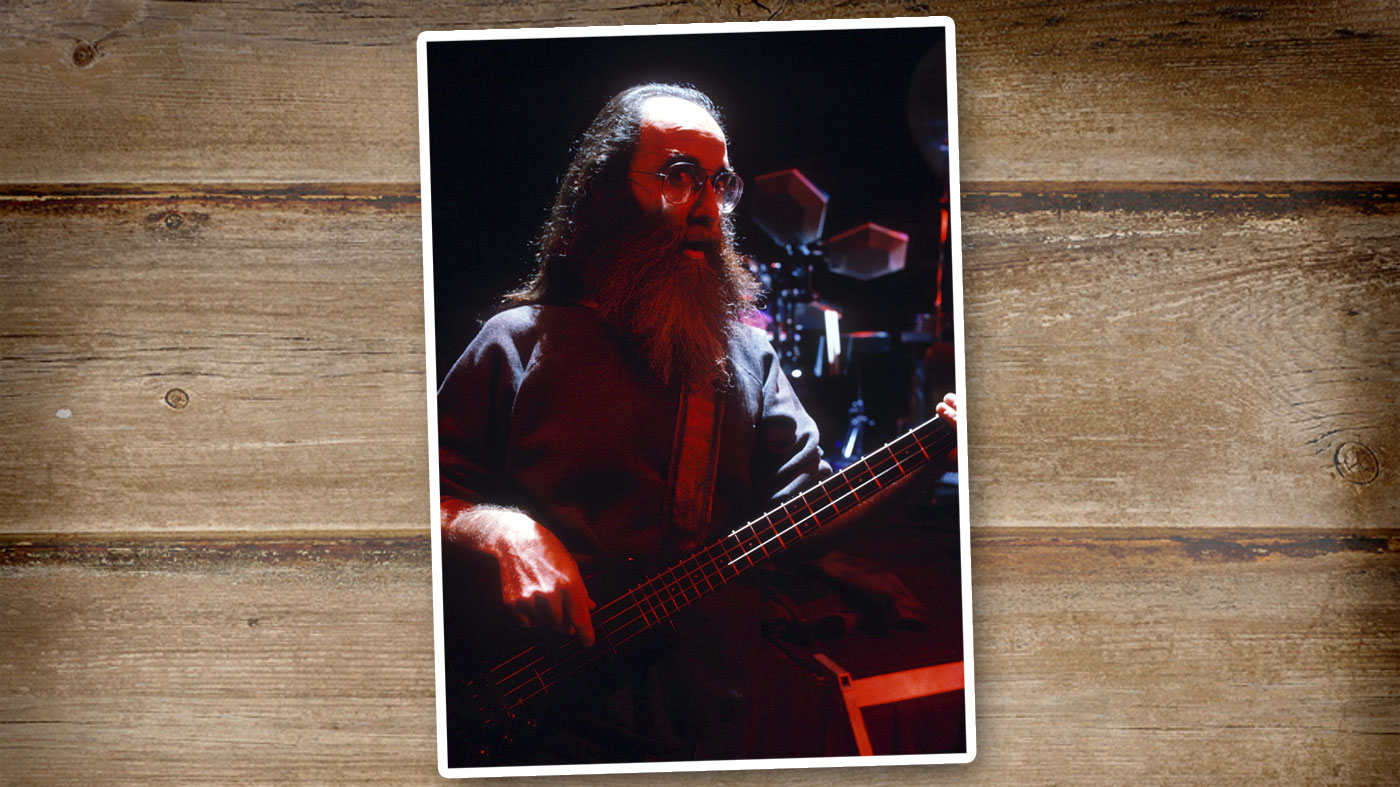

If you’ve switched on the radio at any point in the past 30 years, chances are you’ve heard Lee Sklar’s bass playing. The man has played on over 2,000 albums - let’s just let that sink in for a moment - and has waxed hits with everyone from Ray Charles to Rod Stewart, plus over a dozen milestone albums with long-time musical compadre James Taylor.

When we meet Lee, he’s poised to play a show with singer-songwriter Judith Owen at London’s trendy Hospital club, owned by Dave Stewart. To indicate how little Lee’s behemoth career has affected his sense of humour, we’ve only been chatting for a few minutes when he ropes us in to his ongoing project to take portraits of everyone he encounters on his travels, from mega stars to room service, ‘flipping him the bird’ - otherwise known as giving someone the middle-finger salute… We duly oblige, of course, and Lee kindly returns the favour during our photography session for this feature (in case you’re wondering).

Despite his penchant for a ribald gesture, Lee’s one of the most intelligent, thoughtful commentators we’ve met on what it takes, musically, to transform a good song into an all-time hit and how to become a better, more responsive player. We join Lee to try to put our finger on it…

Don't Miss

Lee Sklar's top 5 tips for bassists

Bass legend Leland Sklar on sessions, gear and getting hired

Taylor Made

“I never thought I was going to be a studio musician. I was in college studying art and science. I was either going to be a medical illustrator or an oceanographer. That’s really where I was headed.

All of a sudden my whole life changed when I met James Taylor

“All of a sudden my whole life changed when I met James Taylor, but I had to learn real fast how to be a studio musician, because suddenly I was in the studio every day. I was really, really lucky.

“Peter Asher insisted our names appear on the records. Before that, there weren’t very many records that had people’s names on them. Suddenly, when James became this huge hit - he’s on the cover of Time magazine, he’s the darling of the media - people could pick up his LP and look on the back and see Leland Sklar, Russ Kunkel, Danny Kortchmar… all our names. When they would get a guy like Jackson Browne, they would say, ‘We want him to have that James kind of vibe,’ so they would call us.”

Going For A Song

“I’ve always considered myself a song player. The song really is everything; the song dictates to me what I need to do.

“I was fortunate that when I met James I was only in rock bands. I was into Cream and Hendrix and Ten Years After, and then all of a sudden I end up with a guy who’s this completely sensitive singer-songwriter, acoustic guitar player.

James Taylor is constantly playing basslines with his thumb. I had to figure out, what am I going to do?

“The interesting thing, for me, was that unlike most of the guys - like the Paul Simons and so many of those guys - is that James has a style of guitar playing that’s so comprehensive. He’s constantly playing basslines with his thumb. I had to figure out, what am I going to do with this guy? Because he’s already covered the bass.

“It required me to think a little bit differently. Even though I always felt like a melodic bass player, because it harkens back to McCartney and Jack Bruce and players like that, this really took it to another level. So, when I would listen to a song I would just try to find what the song wants.

“I was also fortunate that period of time was pre-digital: it was pre-clicks and drum machines and all that, so we never felt that it was a hindrance to have songs that sped up during the chorus and then pulled back. You did what felt right and let the singer carry it.

“Now, some of the singer-songwriters were not that competent as musicians, and they really depended on the players to help create what they needed. But others of them were really, really strong players, and you allowed their performance to dictate what you were going to do.”

Stills Life

“I was always a huge Buffalo Springfield and CSN fan, so to be able to do some stuff with Stephen Stills was really great. It was dead of winter, so we were stuck in the studio pretty much.

Stephen Stills and I are still friends. I’ve worked on stuff over the years with him, but he’s very intense

“You walked outside and you were in a snow drift, but it was great. Stephen really had his own focus and what he wanted to do on this stuff - as compared with James, who would just sit and play his guitar and we would create the parts around him.

“Once in a while, he would come up with a thought on stuff, but for the most part he let us run with what we thought was right. Whereas Stephen wants specific parts and ideas. He wasn’t afraid to grab your instrument out of your hand and show you what he wanted on it, which can be exasperating at times - but I look at it as: it’s his project. I want him to be happy.

“Stephen and I are still friends. I’ve worked on stuff over the years with him, but he’s very intense. You’ve got to be ready for Stephen when you work with him. I’ve worked with every kind of personality in this business, so I subordinate that stuff. I go, ‘Look guys, we don’t have to go to dinner after this. Let’s just make the best record we can and then see you later.’”

Follow The Leader

“I’ve always felt as an accompanist you’re not dragging the artist along, you’re sitting right behind them and following their lead. Like when we’re cutting with Judith Owen, we’re not cutting to clicks or anything like that.

As a studio musician, you really have to subordinate your ego about things

“You’re going for a performance and not: ‘We’re going to assemble this later. We’ve got 20 takes of that song and now we’re going to sit for two weeks, and cut and paste it all together.’ This is really honest performance material.

“That’s how I’ve always approached these things. I listen to the song and think, ‘What does it need?’ If it only needs whole notes, I’m really good with that. I don’t want people to be hearing bass parts independently of the song.

“I want that bass part to be an integral part of the song, and not just a guy showing off his chops. That’s a tough thing in this day and age. There again, I do tons of projects where we are playing to dead-on clicks and everything is completely gridded out.

“I don’t have a problem with that, either. As a studio musician, you really have to subordinate your ego about things. Every day I walk into a different kind of situation, when I’m doing studio work.”

Taking On Toto

“For me, the really challenging jobs are things like when I went out with Toto a few years ago. They called me and it was five days before the tour started. I had to learn their show in five days.

“That kind of stuff is challenging, where you’ve got to hunker down and just focus on material. The tour I just finished with them, there were no rehearsals, so I had to learn the show, and the first time I ever got to play the show was on stage in Brussels.

Rather than me faking it I go, ‘Why don’t you call this guy? Because he eats that stuff for breakfast every day

“The only rehearsal I had was a couple of minutes at soundcheck. That kind of stuff is stressful, because you want it to be great and you’re also stepping into a seat where a guy’s been playing for the past couple of years, and playing the shit out of it.

“For the most part, while studio work can be challenging, it’s never been one of these things that’s really difficult. Once in a while you get called in on a project and you feel you’re a little bit over your head on it. I’m pretty honest about these things.

“If I think there’s a guy who I think would be better on the album and I show up there I’ll say, ‘Why don’t we just call so-and-so and have them come in?’ If there’s a ton of slapping and stuff, I’m not great at that. So, rather than me faking it I go, ‘Why don’t you call this guy? Because he eats that stuff for breakfast every day. It’ll turn out better.’”

Duty Calls

“One of the things I’ve always thought about is when that phone rings you have two options: you can say yes or no. If you say yes, there are obligations that come with that ‘yes’.

“You want it to be the best project it can be, and I may not always agree with the process that they’re doing, or I think there could have been a better take or something like that. It’s not my call. I have to go in and do the best job I can for what they want.”

On Difficult Chemistry

“There have been people that, musically, I dread. If I walk in and I see their gear in the room, I know it’s going to be like pulling teeth that day.

At the end of the day it’s not about that person or me, it’s about the artist. They’re living and dying by that day

“They’re great players, it’s just for some reason we don’t gel or it doesn’t feel right, or their concept of what a song needs to be is so different than mine. You try to massage that the best that you can, just because at the end of the day it’s not about that person or me, it’s about the artist. They’re living and dying by that day. So, you do the best you can and you try to work and work the stuff out.

“There are other times where if somebody calls me and go, ‘Is there a keyboard player you could recommend?’ I know who I’m not going to recommend. That’s the only thing you can do at that point is have a ‘do-not-play-with’ list. But it’s a very short list. It’s like life. There are always going to be those few pant-loads that you just go, ‘No, please not him.’”

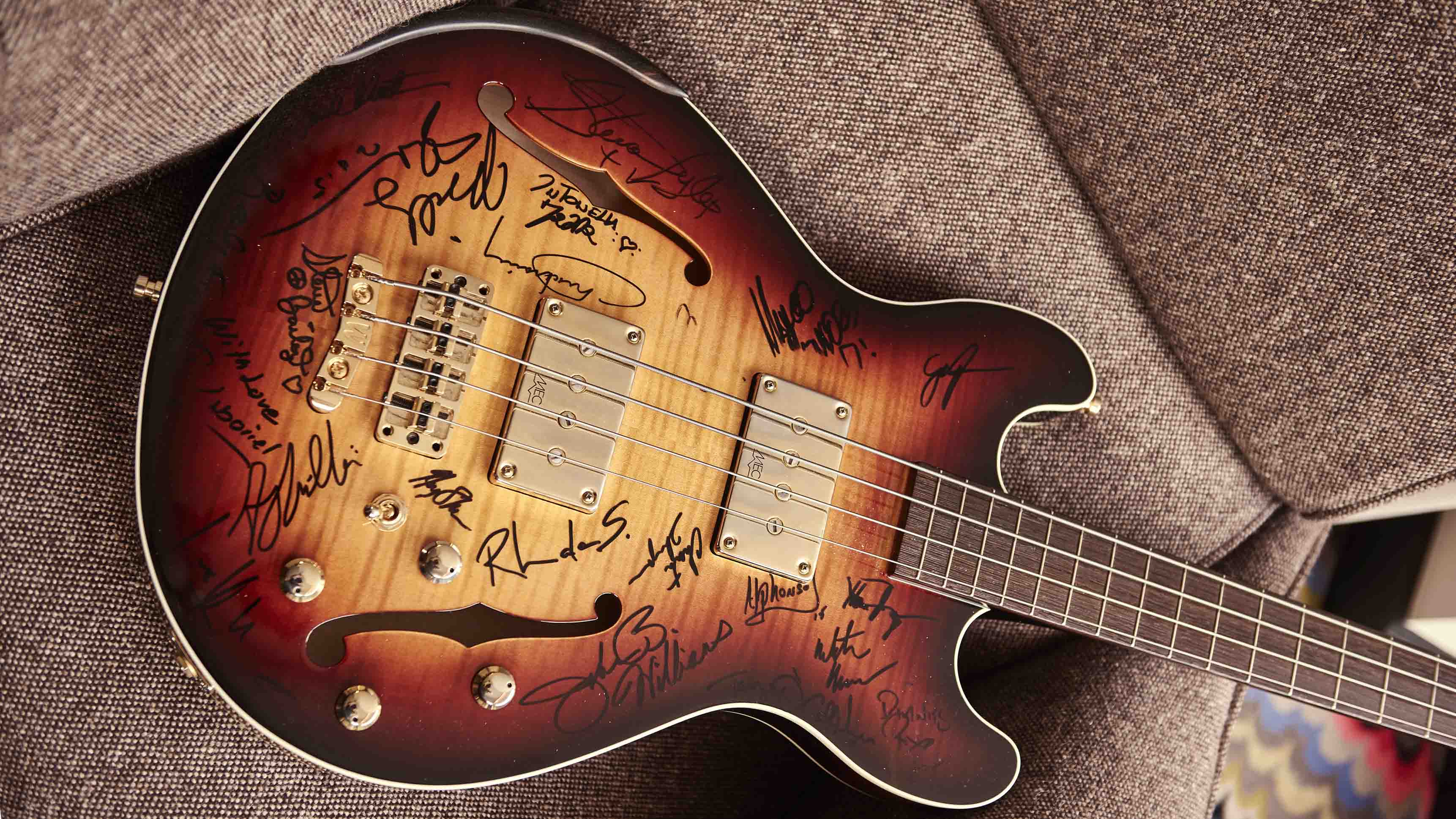

Creating ‘Frankenstein’

“For some reason I ended up with a ’62 Precision Bass neck. I’m not a P-Bass guy. I like a jazz bass. I had a ’62 Jazz Bass.

“The great watering hole in Los Angeles for musicians, in the old days, was Westwood Music. Fred Walecki owned the place and his main repair guy was a guy named John Carruthers. I ended up with this neck and I thought, ‘Gosh, I should do something with it. It’s a really good neck.’

“This is when Charvel first came out doing replacement parts. They were in an area called San Dimas, which wasn’t that far from me, so I went there. I looked and there was a stack of these older blank P Bass bodies sitting there. I just picked each one up and I hung them from a piece of wire and just hit them.

I always call it Frankenstein in my interviews, because it’s really like body parts assembled into a person

“Just one of them went ‘boom’ and so I said, ‘I’ll take this one.’ I then took it to John and we contacted Rob at EMG and we got two sets of Precision pickups. They were the very first pickups where they had a big EMG embossed on the top of them. We just worked on this thing. I always call it Frankenstein in my interviews, because it’s really like body parts assembled into a person.

“We decided to put the two P pickups where the Jazz pickups would’ve gone, but I thought by the nature of the E and the A string, they could use more clarity than the D and E, so we flipped them over so that the bottom half of each of those pickups was closer to the bridge.

“We used the P routing that was in the thing and put two nine-volt batteries in that. And while this was being done, I brought in my ’62 Jazz and we took a template off that neck. John was reshaping that neck into a Jazz neck. In order to do that, he stripped the frets out of it.

“While he was doing that I just walked around his shop and I saw all these spools of fret wire. I said, ‘What’s this wire?’ and he said, ‘It’s mandolin wire.’ So I said, ‘Let’s try that.’ And he said, ‘That’s not good,’ but I said, ‘Let’s try it. The worst that happens I’ll pay for another fret job if this sucks.’

“Well, it was the greatest thing I ever did. That bass I’ve used on probably 2,700 albums and toured with it for years - and I’m on my third refret. It’s not like because they’re small they got ate up - I’ve always used round-wounds and I play hard - but the thing was, you could lighten your touch and you could do glisses where people would say, ‘I’d swear that’s a fretless.’”

Don't Knock Collins

“I love working with Phil Collins. He’s one of my favourite artists I’ve ever worked with, as a drummer.

Phil Collins' philosophy was always that the first audience of the tour deserves as good a show as the last audience of the tour

“Now he’s thinking of re-entering the workforce, although I don’t think he’ll be playing that much drums, because he’s had so many problems since his back surgery. To me, he could just stand up there, play a little piano and sing; his pop sensibility is so strong.

“I cherish all the years I’ve spent with Phil. I’ve never known a guy who cared more about an audience than he does. His philosophy was always that the first audience of the tour deserves as good a show as the last audience of the tour.

“We would spend a month just 12 to 15 hours a day fine-tuning a show, so that first show would be killer rather than bands that go out and say, ‘We’ll spend the first two weeks working out the show.’ It’s not fair to people that have dropped some dough to see you. It’s really uncool as far as I’m concerned.”

Way Of Life

“I feel so blessed at what I’ve been able to do in this business and the fact that I’m still at this point - I thought I’d be out to pasture a long time ago. The only time it’s ever frightening is when you walk by a reflective surface, and you go, ‘Who’s the old dude? Somebody broke into my house.’ Then you realise it’s you. It’s a funny business, but I wouldn’t give it up for anything.”

Don't Miss

Lee Sklar's top 5 tips for bassists

Bass legend Leland Sklar on sessions, gear and getting hired

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.