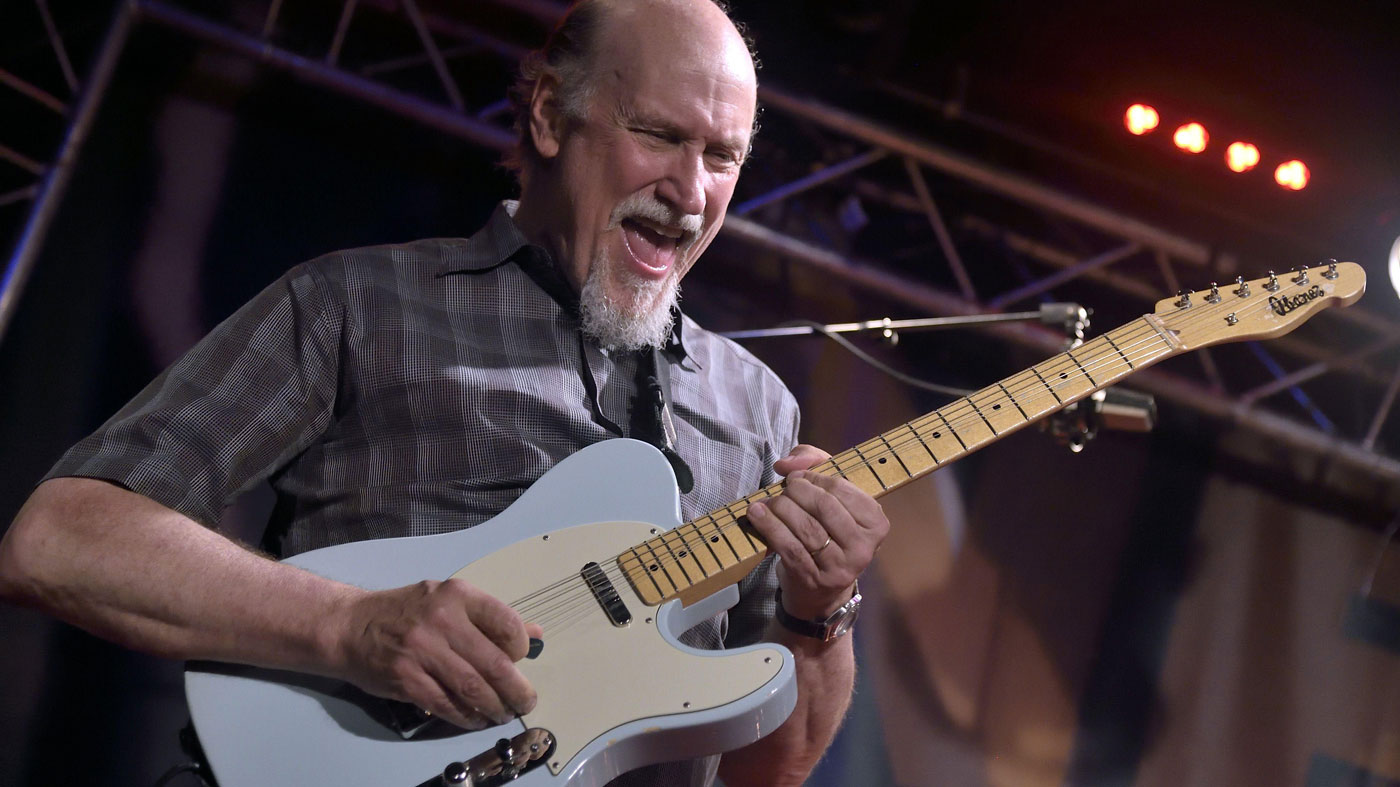

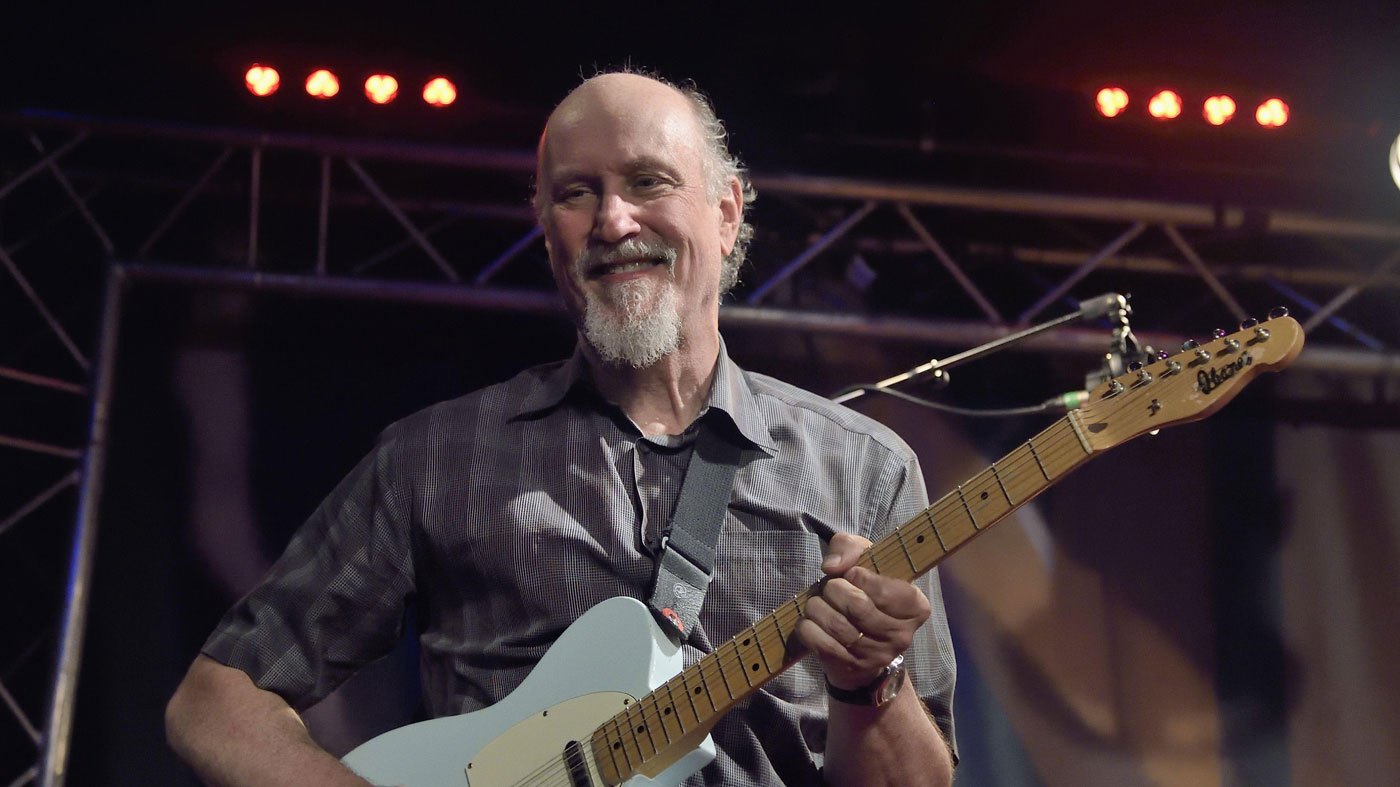

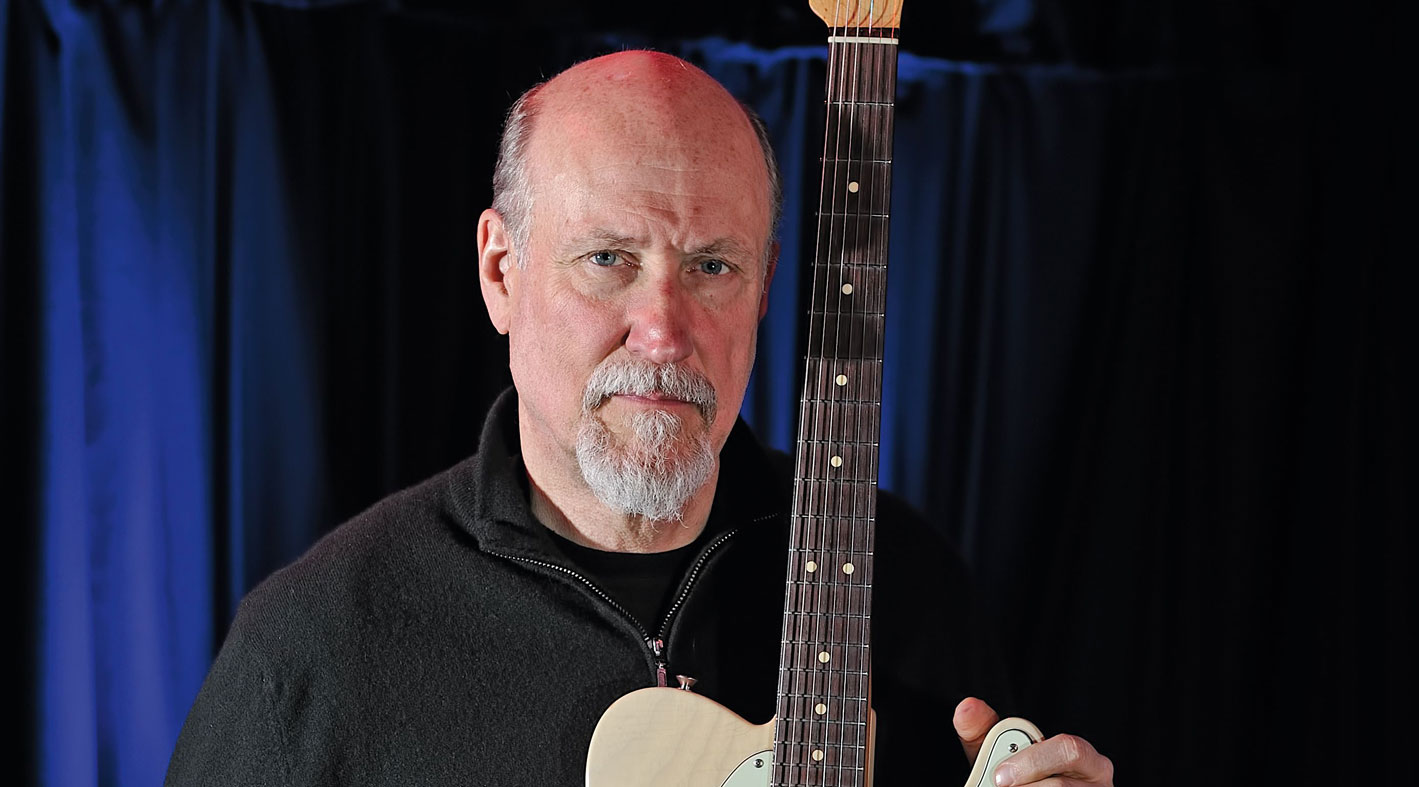

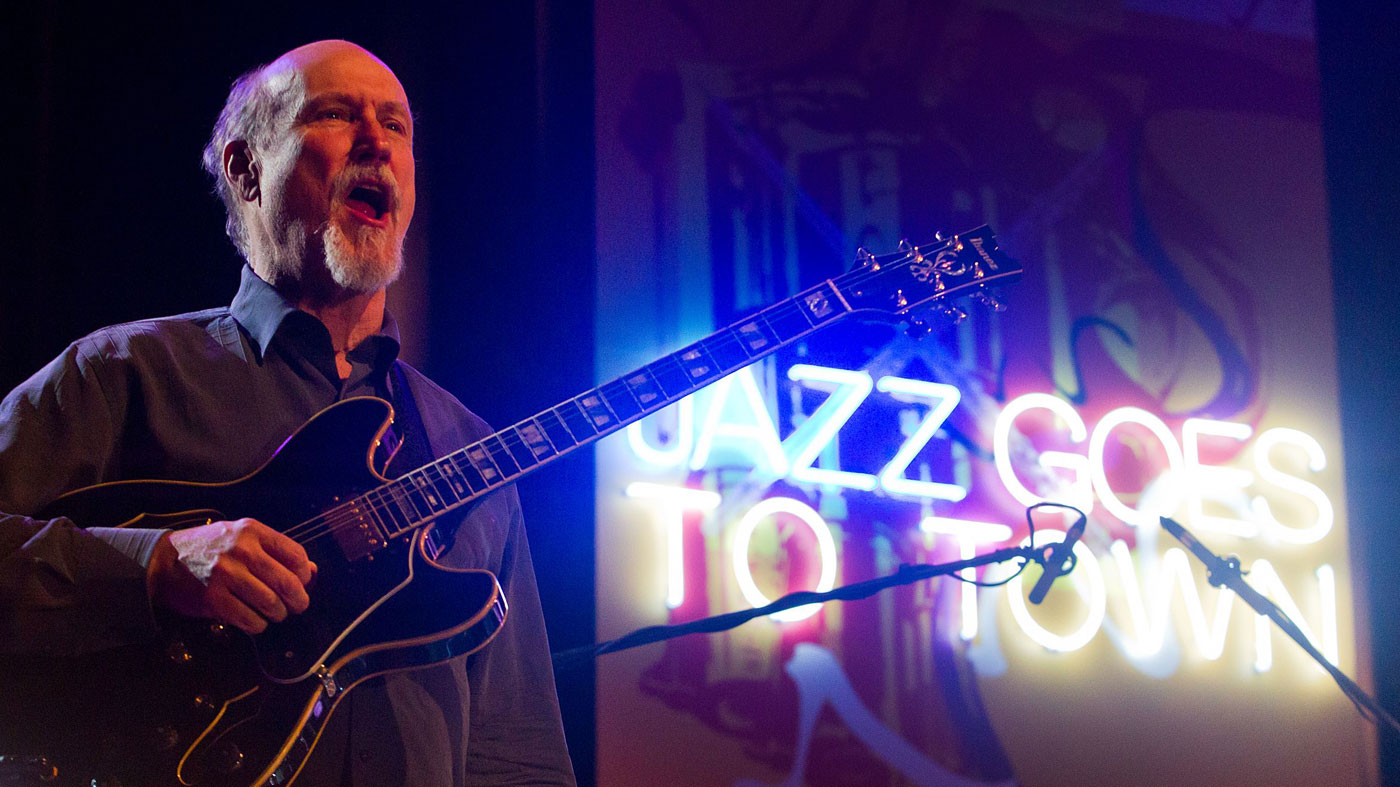

John Scofield's 9 tips for guitarists

Wise reflections from the fusion fret wizard

Introduction

For his most recent album, Past Present, master fusion player John Scofield decided to revisit one of his earlier line-ups by inviting tenor sax player Joe Lovano and drummer Bill Stewart into the studio.

Along with fellow fusioneer John McLaughlin, Scofield’s playing is regarded by many as a vital step in the evolution of post bebop jazz

The quartet was completed with Sco’s mid-90s touring partner Larry Grenadier on double bass and the result is, as you might imagine, another sublime example of highly polished playing through nine original compositions.

Along with fellow fusioneer John McLaughlin, Scofield’s playing is regarded by many as a vital step in the evolution of post bebop jazz. As such, he is the perfect sounding board to reflect on the genre’s current status. Is the culture of jazz still alive and kicking? Or was Zappa right when he noted that, “Jazz isn’t dead, it just smells funny…”?

Don't Miss

John Scofield on his workhorse Ibanez and advice to his younger self

1. Face up to the challenges

“I think the problem with jazz music internationally is we have this incredible history and it weighs very heavily on the player who falls in love with jazz but then has to come up with something to play that’s compelling music.

You get into the thing of changing music just for the sake of change and sometimes it ends up being not so good.

“If they play a lot of the music they fell in love with, they’re just playing the same old stuff and maybe not as good as the masters who did it. It’s easy to be part of a movement; you’re on this train, it’s moving and you just play. So that leaves you with a few options: either you just play standards and get into it and say, ‘What the hell? I’m just going to do that…’ - and that’s a noble endeavour - or try and change it, and then you get into the thing of changing music just for the sake of change and sometimes it ends up being not so good.

“On a good note, I think there are incredible young musicians out there that are so capable on their instruments, and people who have gotten jazz together so quickly because of the availability of material, online and all. I mean, just astounding capabilities; it took me years and years where it takes other people a couple of years. I’m pretty amazed.”

2. Be cool for school

“If you’re going to learn jazz, Charlie Parker learned to put his shit together by really serious study, and he was a genius. Thelonius Monk put his music together from serious study, too. It’s not like blues or church music, where it’s all about soul.

Jazz is about a bunch of things, but I think unfortunately, it’s gotten academic and it’s taken away a lot of the personality

“Jazz is about a bunch of things, but I think unfortunately, it’s gotten academic and it’s taken away a lot of the personality and soul. Some of the aura of jazz, when I was growing up, was this really cool thing that these very, very exotic people originated and I just loved it and wanted to be part of it.

“Everybody who played it was this kind of wise person that had gotten to a place, an understanding, because they were great artists. But I’m 63 years old and nothing is as idealised as it is when you are a kid!”

3. Keep your ears open…

“I went to music college - I went to Berklee. I wanted to play more than anything and I wanted to play from listening to the records and hearing jazz musicians play.

People that were saying it’s bad to learn music theory and it’s bad to learn to read music - it’s really a dangerous fallacy

“If you’re stupid enough to go to music college and expect them to teach you how to play, then you are never going to be any good. You go because you have the passion and the desire.

“Everybody has to play by ear. Some people that were saying it’s bad to learn music theory and it’s bad to learn to read music - it’s really a dangerous fallacy to promote that. To play jazz, you have to play by ear. I don’t care if you’re the greatest theoretician, if you’re Coltrane - who was a theoretician - or Charlie Parker, who knew everything about music.”

4. …but keep the brain engaged

“Every jazz musician has to learn to play by ear or you can’t improvise, you’re just improvising bullshit, you’re moving your fingers around.

People might say they’re not utilising theory, but they are. It may be just some home-grown system

“That development of the ear is essential, but we also have brains: when you sing a melody you realise it goes up, and if you think about it, after a while you realise it goes up in steps.

“They say George Benson plays by ear. He totally understands whole steps and half steps and minor 3rds and the construction of chords, and sings it and plays it all the time. Of course you play by ear, but your mind is also thinking about the geometry of music. The mathematics involved in going up a whole step or a half step or a minor 3rd or a major 3rd and the 12 keys, the cycle of 5ths.

“First of all, people might say they’re not utilising theory, but they are. It may be just some home-grown system, but it’s one that’s helped them to understand.”

5. Write with purpose

“I write on the guitar and it starts by coming up with the chords and the notes at the same time.

When I just write music without any assignment, it’s harder

“Beforehand, I usually give myself an assignment: I need a fast tune, I need a slow tune, I need a waltz, I need a straight-eight kind of feel, and then I try to come up with something. When I just write music without any assignment, it’s harder. When I write music, I just write notes and the sound may be melancholy or happy or somewhere in between those, but it’s a feeling, a musical feeling.

“I never draw from life and I think Duke Ellington, when he would say, ‘This is a song that sounds like the Harlem air shaft’, I mean I really admire him, he was a genius, but I think he was bullshitting when he did that. That’s just a way that instrumental musicians have of trying to help the audience so that people will like their music.”

6. Pick your titles carefully

“I think that [Tchaikovsky’s] 1812 Overture was not really about cannons and about the 1812.

I think that music comes from another place, has its own language and it may sound like something after the fact

“He may have assigned himself, ‘I’ve got to write something and they want this piece of music that’s supposed to be about this battle, so I’ll write some stuff that’s explosive.’

“He might have done that, I don’t know. But I think that music comes from another place, has its own language and it may sound like something after the fact. That’s how I title my tunes. My wife helps me and says, ‘How about this?’ and then we come up with a title that reflects something of the feeling of the song, but it’s never about anything.”

7. Stay in the moment

“You can’t play good music without having roots and all these styles and things that came before. And that’s the past. Good music, in a way, is history and a really good jazz musician is supposed to have this vocabulary of music.

In order to play music, you have to be in the moment. Otherwise, you’re just reciting

“We do have vocabularies, expansive vocabularies, and that’s reflecting what we love, which means it’s from the past. But, in order to play music, you have to be in the moment. Otherwise, you’re just reciting. That’s just a little bit dead, if you’re reciting what you already know.

“When you improvise, which is the main thing I’m trying to do, you get into this mindset of really being in the moment, so what comes out is coming through you and it comes from your past - but it’s in the moment if it’s going to be any good. Not that you’re inventing the music but you’re letting it come through you.”

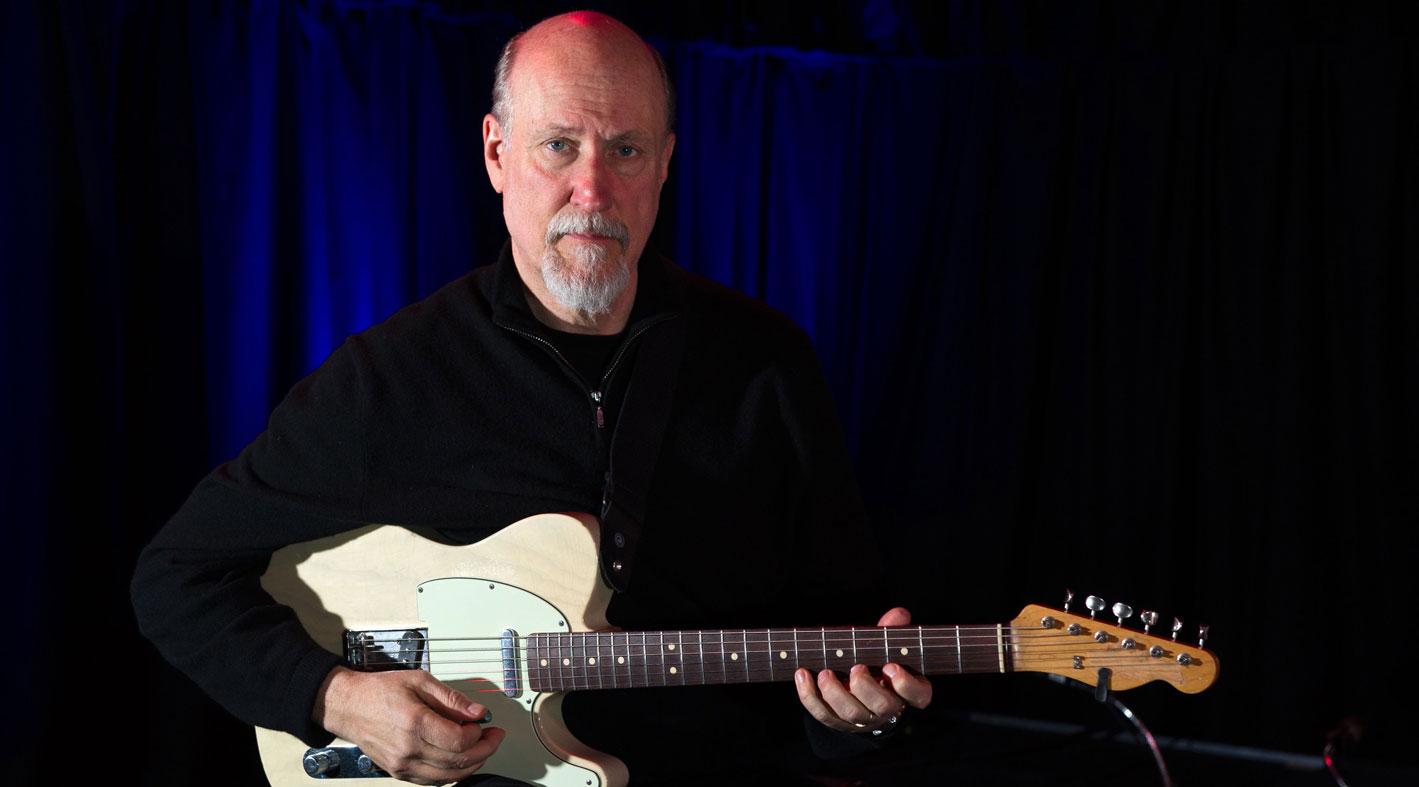

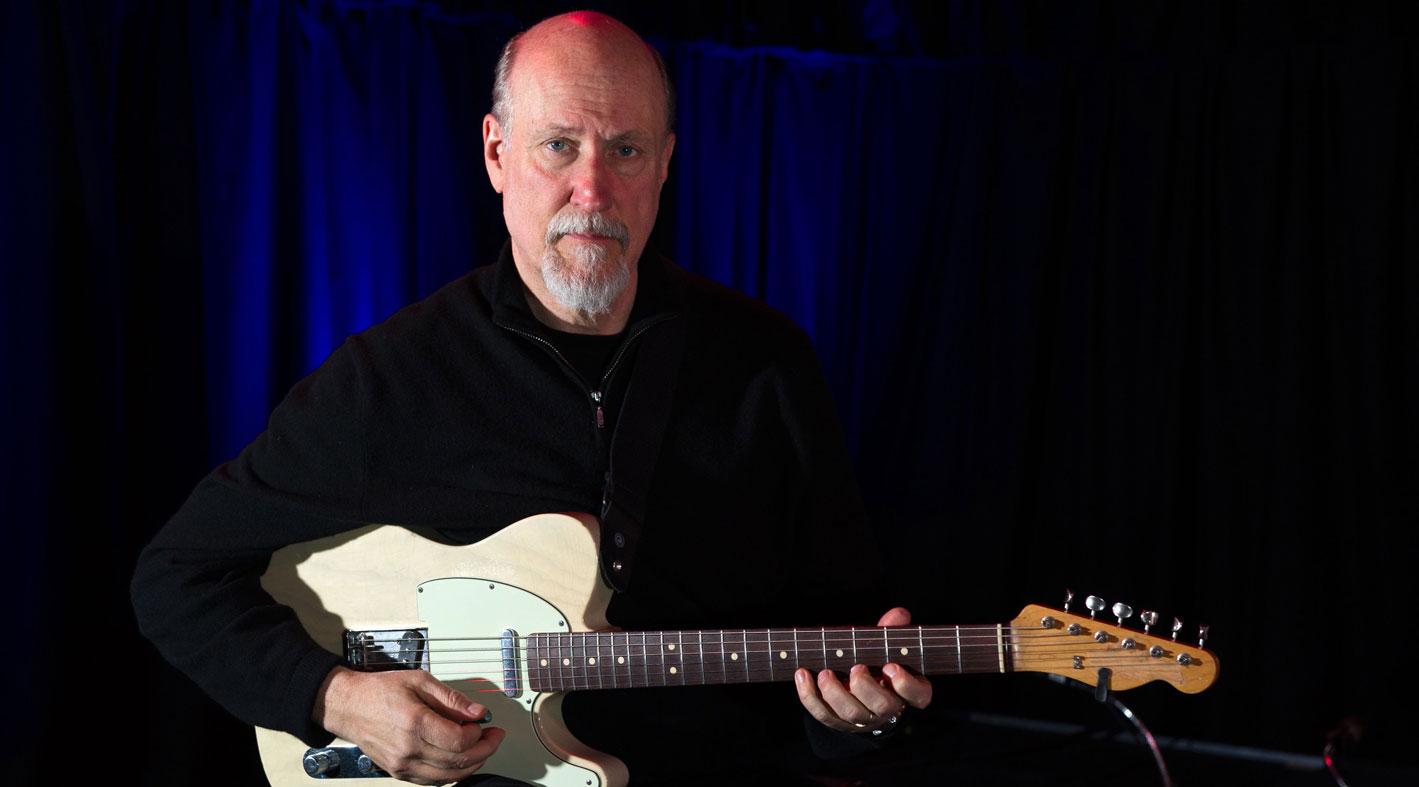

8. Keep refining your gear

“I play an old Ibanez that came from before they made the Signature Model. It was called the AS200 and it’s from the 80s, a 1986. I have two of them, one from 1982, the Sunburst, and a black one from 1986.

I played through a Deluxe Reverb amp that I have; that’s from 1964

“I changed the pickups on the ’86 and I put on these Voodoo pickups in that are really cool, I think - they sound like old Gibson humbuckers. [On the latest album] I played through a Deluxe Reverb amp that I have; that’s from 1964 and there’s no pedals or anything. It’s just right through the amp.

“I used to use distortion pedals but lately, the last 10 years, I’ve been playing amps like the Fender Deluxe or the Vox AC30, which I like a lot; it’s just louder. But they distort naturally, you just turn them up and there’s a little fuzz going.”

9. Remember, music is a vocation

“I think any of us that get into music do it because we have to and that’s essential. You have to be ready to wash dishes for your whole life, really!

If you just sit in your room and wait for your big break, it’s not going to happen

“When I was a kid I just wanted to be part of the scene. I was ready to give guitar lessons at a shitty music store and have that kind of existence and I’ve done a lot better than that and I’m really grateful.

“The other thing is, if you want to play music, get your ass to a place where there are musicians a lot better than you and hang out with them and that’s how you do it. But if you just sit in your room and wait for your big break, it’s not going to happen.

“You have to be on some sort of scene, so if you were in England you would probably go to London… I went first to Boston, but then down to New York as soon as I could. And I think playing with other musicians will make you get better way fast.”

Don't Miss

John Scofield on his workhorse Ibanez and advice to his younger self