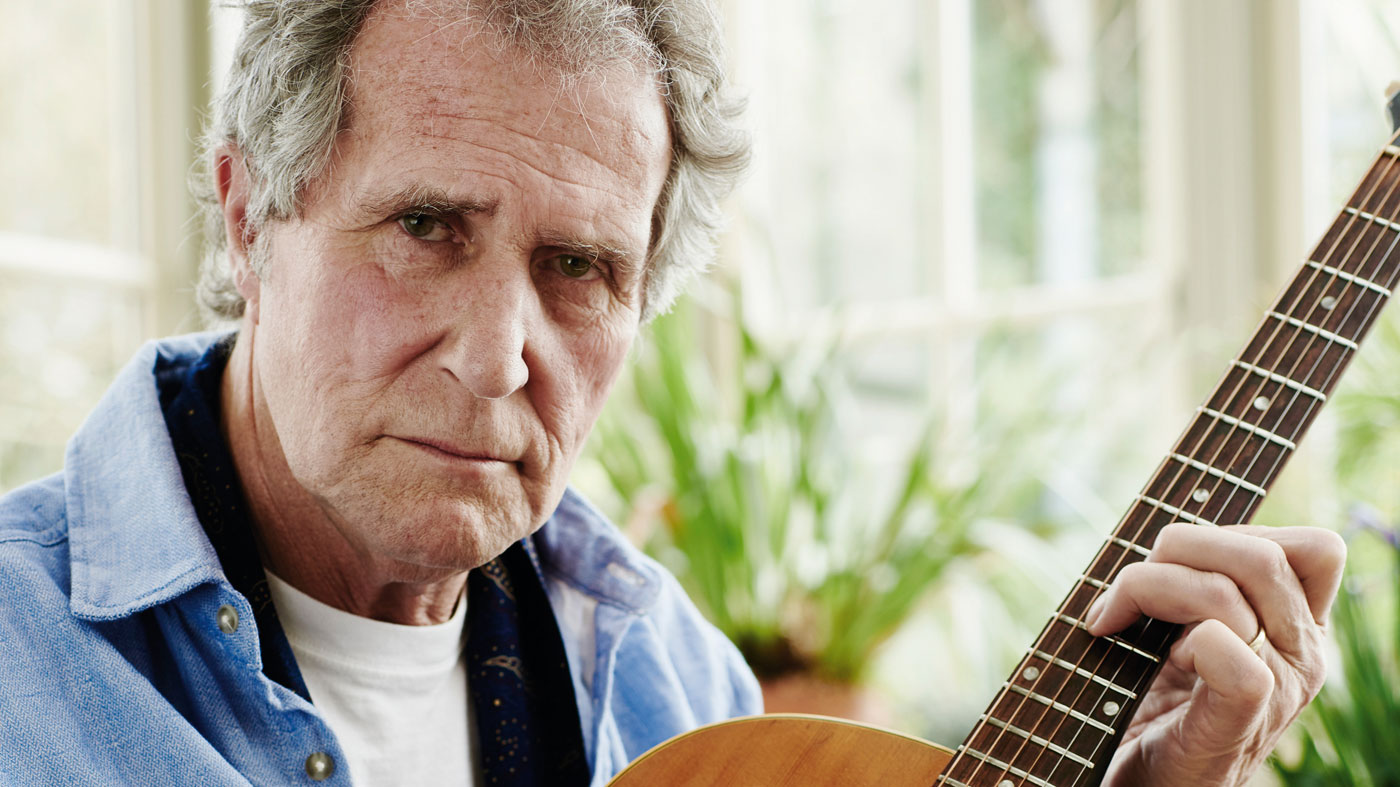

John Illsley talks Dire Straits, Long Shadows and favourite gear

The bassist on his past, present and future

Introduction

The Dire Straits bassman reflects on the glory days of huge world tours and his latest solo album, Long Shadows, as well as giving us a look at a few choice pieces from his guitar collection

We’re sitting in the conservatory of John Illsley’s Hampshire home and mulling over the subject of how some bass players begin their careers on the instrument. We remember how Paul McCartney once said quite a few started off as guitarists, deferring to bass when they found that all the guitar jobs were already filled in the bands they auditioned for.

I just thought about music all the time and I couldn’t help it - and, as a consequence, I left school with very little apart from an Art A Level

“You know, I think what Paul said is probably quite relevant,” says John. “I think a lot of people end up being bass players because there’s already a guitarist in the band and if you want to join you have to play the bass - and that’s exactly what happened to me.”

After a considerable tenure with Dire Straits, John has now put his own band together in order to tour with his new solo album, Long Shadows, on which he plays both bass and rhythm guitar.

“I’ve often thought with this band I’ve got now whether I should play the guitar or whether I should play the bass,” he says. “It’s quite a difficult decision to make, but I said, ‘Nah, I’ve got to play the bass because then I know that the engine room is solid…’”

So, going back way before the days of touring the world with Dire Straits, what piqued your interest in music?

“I started listening to music in ’60 or ’61 when I was 11 or 12, I suppose. Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry and then, of course, The Beatles and The Stones came along. So, I grew up at what I think was probably one of the most exciting times for music. I wasn’t particularly academic, so I wasn’t crazy about reading or chemistry or physics or anything like that.

My brother, who is incredibly good at woodwork, built me a bass in the woodwork department and I used that for a bit

“Essentially, I just thought about music all the time and I couldn’t help it - and, as a consequence, I left school with very little apart from Art A Level and the ability to throw a few chords together. It became a pretty big obsession in my life and I just absorbed everything that was going on.”

Did you go through the whole high-school band thing?

“Yeah, that’s where I started, really, playing things like Lawdy Miss Clawdy and Roll Over Beethoven, and all that sort of stuff. You discover that’s where a lot of people start and that’s the reason why I started playing bass, because my brother was in a band playing guitar.

“There was another guy who was trying to play electric guitar in the band, as well as a drummer and a keyboard player and they said, ‘Well, if you want to join you’ll have to play the bass.’ And, funnily enough, I borrowed a violin bass; one of the other kids in the school had one of the McCartney Höfners.

“So, I borrowed that for a bit and then my brother, who is incredibly good at woodwork, built me a bass in the woodwork department and I used that for a bit and then I bought something of my own.”

Don't Miss

Going Strait

How did you end up meeting Mark Knopfler and forming Dire Straits?

“I was living in a council flat in South East London and David Knopfler [Mark’s younger brother] was my flatmate. Mark used to come down at weekends and we used to hang out. At the time, he was playing in a band called the Café Racers, a rockabilly band, and I joined them for a couple of gigs because the bass player was away doing something or other.

“Mark and I would just play together in the flat a lot. Things were feeling right between the pair of us and we realised we enjoyed the same kind of music. One thing led to another and we said, ‘Why don’t we get our own band together?’”

Dire Straits had its beginnings in what has become known as ‘the punk era’. Was it difficult to break through?

[People call it] the punk era as if nothing else was going on. But you’ve got Graham Parker and The Rumour, and you had The Police… Dire Straits was just a part of all that

“There was a lot of other music going on apart from punk. The problem with history is that it tends to put things into pockets and they labelled that whole era - from 1975 up to about ’79 or ’80 - as the punk era as if nothing else was going on. But you’ve got Graham Parker and The Rumour, and you had The Police… Dire Straits was just a part of all that.

“But it was very difficult to get gigs back then, because you’d ring up and say, ‘We’d like to come and play there.’ And they’d say, ‘What are you? A punk band?’ ‘No, it’s not a punk band, we write our own stuff and…’ ‘Oh no, we don’t want that kind of thing, we just want punk’.

“But then we played at The Hope And Anchor [in Islington] and they loved what we did. Then we played at The Rock Garden in Covent Garden and they gave us a residency. We played at The Marquee Club, too, so there were places to play. It was all going on. Then, of course, the punk thing fizzled out. Everyone thought, ‘That’s enough of detuned guitars and bad language.’ So everything has its time.”

When we interviewed Mark, we were talking about Brothers In Arms - he said he thought the success of that album was pretty much due to the fact it was one of the first big albums released on the new CD format - would you say that was true?

“Yeah, I think so. The CD revolution then was pretty major, but don’t forget the band had already had four albums out there - five if you count Alchemy - and had already notched up a serious amount of record sales. There was a big audience for Dire Straits then.

Brothers In Arms could have been written any time, but what a fantastic view of that part of our world.

“We’d done a lot of touring, a hell of a lot of touring. We were literally on the road all the time in the early 80s before we settled down and did Brothers In Arms, so people were buying albums. Also, there were some pretty good tunes on that album. Brothers In Arms in itself is probably one of the best things that Mark’s ever written and Money For Nothing was a pretty seminal moment with MTV coming out.

“It was an observation of a particular time in the music industry and really captured people’s imagination and, of course, Brothers In Arms could have been written any time, but what a fantastic view of that part of our world. That song could have been written 50 years ago; it could have been written 50 years from now. It would still be relevant and it will always be relevant, because it resonates.”

The tours you did with Dire Straits were absolutely mammoth. Do you miss all the intense activity from that period?

“Well, I’m not sure I’m fit enough to do them any more [laughs]! I think I’d be a liar if I didn’t say I missed a bit of that, but it was of its time, and when there’s that kind of energy going along, you either become a part of it and go for it, or you don’t. You’re fit and young and healthy. It’s like every schoolboy’s dream, isn’t it? And you just go along with the journey. You couldn’t have dreamed that one up.”

Big and small

A lot of people who have spent long years on the road doing huge gigs in stadiums say they miss the romance of doing small gigs - is this the case with you?

“Well, this is true, actually, and I have to say I’m having the time of my life at the moment. It is incredibly pleasing to have people three or four feet away from you. Apart from anything else, it makes you really concentrate, it makes you very aware of how vulnerable you are, in a sense.

Our manager said, ‘These are all your trucks. There’s 48 artics…’ and I went, ‘48 artics? Okay. Now it’s big.’ And I thought, ‘Where can you go from here?’

“Whereas when you’ve got this great machine going on with the lights and there’s a 30-yard gap between you and the audience… It’s all very nice with your planes and your cars and your crew and everything like that. I’ll never forget at the end of the On Every Street tour - we were in Rotterdam, I think, and because of the scale of the staging we had to have two sets of equipment. This meant we could leapfrog stages and lights and the rest of it, and still be able to play four or five nights a week.

“There was one time when all that stuff came together and I got picked up at the hotel. We were on the way to the gig in Rotterdam and we were doing two or three nights in this enormous 80,000-capacity place or whatever it was. It was at the culmination of the tour.

“We drove into what I thought was a lorry park and I was with my tour manager and I said, ‘Why are we driving through a lorry park? Where’s the gig?’ and he said, ‘No, no. These are all your trucks. There’s 48 artics…’ and I went, ‘48 artics? Okay. Now it’s big.’ And I thought, ‘Where can you go from here?’”

You’re out performing your own music now and playing smaller venues. What’s the contrast like?

“It is what it is, you know? I can’t command big audiences, that’s the fact. If I went out as a Dire Straits tribute band, of which there seem to be quite a few these days, then obviously I’d pull, but that would be dishonest of me. I’m making my own music and writing my own songs. I’ve got enough music to do a whole show of my own stuff with no problem at all. I choose to play some of the Dire Straits songs because I really love playing them and I think people would probably expect to hear them, too.

I can’t command big audiences, that’s the fact. If I went out as a Dire Straits tribute band, then obviously I’d pull, but that would be dishonest of me

“I’ve really enjoyed the last few years; I really enjoyed getting back into music - I gave it up for a while in the early 90s because I just needed to cleanse myself a bit, and I started painting. So, I did that for a while and then, when I got back into music, I started writing and started really enjoying that part of it and I think I’m getting better at it. It’s a bit late in life to discover that you write some pretty decent songs, but that’s fine and I’m really pleased with this last album.

“So, I’m enjoying the process, I’m enjoying putting together a band. I’ve got a really nice bunch of people I’m playing with now: Robbie McIntosh is a great guitar player, which you probably know; Paul Stacey is playing with me this time, which is great; and the rhythm section is me and Stuart Ross, the keyboard player Steve Smith and Jess Greenfield doing the vocals with me. It’s very low key, because that’s the way it is.

“If I suddenly started commanding audiences of 1,000 people that would be marvellous, but right now it’s anything from 250 up and that’s great. It’s a small crew: two guys and a van, a tour manager and a six-piece band. It’s very manageable.”

Gretsch Country Gentleman

“This came from John Entwistle and I’ve used this guitar on just about every album that I’ve ever made - it’s either a ’65 or a ’67, I can’t remember.

“The electronics on these things are so weird - there are only a couple of people who know how it all works! It’s got a sound that is completely unique.”

1963 'Dire Straits' Jazz Bass

“This is the guitar that I used pretty much from the mid-80s and the strings haven’t been changed since, so they’ve been on there for 30 years!”