In the first part of our interview with John Fogerty, the music legend talked at length about the making of his superlative new album, Wrote A Song For Everyone, on which the original chooglin' man duets with a glittering array of stars - Brad Paisley, the Foo Fighters, Miranda Lambert, Bob Seger, Kid Rock and others - on a generous selection of Creedence Clearwater Revival and Fogerty solo-period gems.

In part two on our conversation below, Fogerty opens up about how he crafted some of Creedence's music and worked with his former band. These are subjects he hasn't always warmed up to: Following CCR's acrimonious breakup in 1972 and a protracted serious of legal battles with Fantasy Records, Fogerty refused to perform his old hits live. It wasn't until 1997 that he began to reconnect his back catalogue and make peace with the astonishing first chapter in his creative life.

You've played a lot of different guitars during various phases in your career. Were there any go-to models you used for Wrote A Song For Everyone?

"Probably my Telecaster. I'll just loosely say 'Telecaster,' because I used a few different ones. When I played with Brad Paisley, I was using a Bill Crook Telecaster. Brad kind of put Bill Crook on the map. Bill does all of those wonderful Paisley guitars that Mr. Paisley plays [laughs]. I was inspired because Brad is certainly my idol, you know.

"These are some other fellows that make these guitars; they're all takes on Leo Fender's original idea. I played a few different Telecasters throughout the album, but certainly overall I played that one more than any other single guitar. Playing with Brad, playing on Train Of Fools - that's another Tele. On Mystic Highway, I'm playing another Tele. At the end of that song I'm playing a cheap Tele that wouldn't stay in tune - it just refused.

"I remember staying up late one night trying to finish the tail end of the song. The guitar wouldn't cooperate, and it kept getting later and later. I was so depressed about it, and I was running out of time, and they were going to take the record from me. The last weekend that I had a shot to finish, a guitar arrived from a guy named Chad Underwood. He may be a little under the radar, but the guitar he built may be the best Tele I've ever played. So I played it in my little office and was like, 'Oh, my God!' It was so magnificent - and it stayed in tune. I put it on Mystic Highway, and it sounds incredible. I'll be playing that guitar a lot from now on."

During your Creedence years, you used Rickenbackers, Les Pauls - the black '68 Les Paul Custom, of course. Did you have a particular favorite out of that bunch?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Well, I'm schizophrenic. For a certain kind of sound, which I still really, really love, it's a Rickenbacker through a very chimey kind of amplifier. In the beginning, I was playing a Rickenbacker through my Kustom amp - I did a lot of that. That's what Suzie Q is, that's Born On The Bayou, and that's also I Put A Spell On You.

"But a little later, the more chimey kind of rhythm sound, like what I did on the electric guitar on Who'll Stop The Rain and… if I could just think of a few more… Now, a lot of the British bands, including The Beatles, were getting that sound from a Rickenbacker through a Vox AC30, or even a 15. I didn't have a Vox yet, but I had a Kustom that was kind of chimey. Later, I got a Fender Deluxe Reverb that did pretty well.

"I went to the chimey sound rather than the tubey sound of Bayou and I Put A Spell On You. I mean, I recorded those songs that way - that is a Rickenbacker. But then I switched my allegiance, because I had at least heard that Clapton and Page and Beck were playing Les Pauls through Marshalls, and then I started playing my Les Paul through a fuzztone Kustom amp."

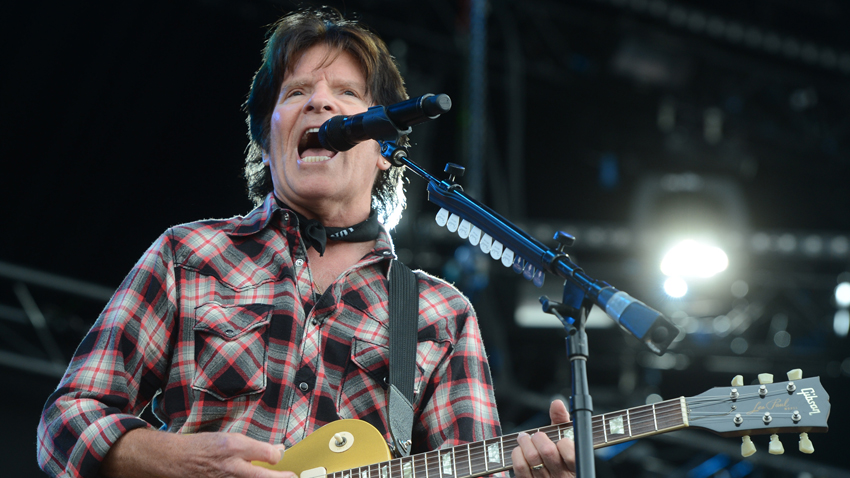

"I went at it with a vengeance," Fogerty says of his Creedence years. "By releasing so much good music to the radio, the competition was over." © Rune Hellestad/Corbis

Those early Kustoms were pretty cool looking - they had the padding on them.

"It's funny - I think I've said this apologetically: I think I'm the only guy who ever had a successful career and got a good sound playing out of one of those amps. For some reason, it all worked for me, but I used to get letters from people: 'Dear John, I went out and bought one of those amps because of you. Thanks, John.' [Laughs] And you could just hear the sarcasm. They were trying and trying, and they just couldn't make it sound like I could; I don't know why.

"The thing with that amp was, it was really clean acoustic when I played it clean, but when I stepped on the fuzz, that's when I went to the neck pickup on my Les Paul - the black Les Paul Custom - and that's when you heard something like Grapevine or Bayou."

Speaking of Grapevine, was that done in one take? It's such a long jam.

"We did it in one take, and it was really great, and then we decided to do it one more time, and that one was even better. That was it. On the second one, there's no overdubs - well, there's congas and cowbells and piano and also the vocals, which I did all of that. But as for the band jamming, that's one take.

"I'm pretty sure I destroyed the first take. The reason why I did that was because I think I'd heard what happened to Buddy Holly. They're always digging up these lost tapes, and they're never as good as the real hit. I didn't want that to happen - foretelling what Fantasy would probably do with these things."

I know you've had your problems with Fantasy, but when you were actively making the Creedence records, did they interfere in the creative process? Was anybody coming by to see if you had "the single"?

"No. No, no, no. Not one iota. They had a tin ear. I mean, this was a jazz label that Saul Zaentz had bought with some buyers, I guess - he was the only guy we knew. He'd been the sales rep of the former ownership, and now he was the boss. But the way conversations went - and this was before the noose tightened on us and we began to see, like, 'Uh-oh, the jig is up. We've been had.' - the feeling was, 'We're all in this together.'"

"You know, we were all dirt poor and going for the gold. It was a shared discovery. We never thought that things would go down the way they did; to us, it was all a joint partnership. Of course [laughs], then it all changed drastically. But Saul didn't mess with the music at all. As a matter of fact, it started right away. We made the first album, which came out on my birthday in '68. I wanted Suzie Q as the single, and Saul couldn't make up his mind, so he put out two singles at once. Suzie Q and I Put A Spell On You were both released at the same time as singles. Suzie Q got traction first, and I Put A Spell On You sort of rose through the 50s, I guess. After that, I came with the songs that I wrote."

With the songs you wrote that were singles, you had the distinction of having an incredible run of double-sided hits. With two strong songs on any given single, was it a toss-up sometimes deciding which one got the A-side?

"Put it this way: I have to give you a mindset. I had looked at our situation - this was probably late summer of '68. Suzie Q was a hit, and it was also kind of defining our vibe. Here was this band with this guy who had the country pickin' thing going on - Suzie Q had the cool little riff that I'd learned from Dale Hawkins, or James Burton, really. A guy on the radio even used that phrase: 'Listen to that good ol' country pickin' on that song.' I felt really proud of that. I knew that this kind of music was connecting.

"I looked our situation. I said, 'Man, we have no manager. We have no publicist. We have no producer. We're on the tiniest record label in the world.' I felt almost death to my bones, to my toes. I thought, 'We're in the position of being the next one-hit wonder.' Our next thing had to be good. I said, 'OK, if I don't have all the things that The Beatles have or the Stones have, I guess I'm going to have to do it with music.'

"I went at it with a vengeance; that was my marching orders. Therefore, since The Beatles always had two good sides, and Elvis in his heyday would have two good sides, I thought that was the way to go. I didn't think of it as getting split play; I thought I was covering the market. By releasing so much good music to the radio, the competition was over. We won! [Laughs]

"I did that for eight singles in a row. Starting with Proud Mary, it was Born On The Bayou, Bad Moon Rising, Lodi, Green River, Commotion, Fortunate Son, Down On The Corner. Somewhere around the fourth single, Billboard, which had been listing the songs as separate numbers, started listing them as the same number. I took that as a slap in the face. It was like we couldn't have two different songs in the Top 10 like The Beatles."

"I played a few different Telecasters throughout the album," Fogerty says he the guitars used on Wrote A Song For Everyone." © Denny Mack ./Retna Ltd./Corbis

Creedence were very well received in England. For a bunch of guys who grew up loving The Beatles and the Stones, was that mind-blowing?

"Oh, absolutely. To go to the Royal Albert Hall and do very well, and to hear people say such nice things, it was incredible. We were accepted by the very people we admired. I think I remember reading something John Lennon said: 'I love Creedence. They make lovely Clearwater music' - something like that. I met George a couple of times - this was later on, of course. At the Palomino one night, I made my way into the cloak room, and George was hiding in there having a smoke. I said, 'Hi, good to see you,' all that, and he said to me, 'Well, the band really liked your band.' I thought about that later - The Beatles really liked my band. It was like he was back in his 14-year-old shoes relating to my band, probably in our 14-year-old shoes."

Musically, were Creedence an easy band to work with? Did the other guys know instinctively what to do with your songs, or was it a struggle sometimes?

"Here's the funny thing: Everybody knows that I grumbled for years and years afterward; I was grumbling at the time, though, because the guys in the band were so clearly starting to break away. They were starting to make noises about writing songs and acting really angry or belligerent. I didn't get it: 'Why is everybody acting this way?'

"It was hard for me to understand because I was providing something that made us winners. Here we were, succeeding at something that we sat around the coffee table and talked about, probably from the time we were 16 - it was such an unimaginable goal. Nobody we knew was at the place we were at as far as worldwide acceptance. So when the guys talked in such an angry way, there were some words and emotions that weren't in my lexicon. This took years, when I talked with Julie and she pushed me into seeing a shrink. The shrink gave me a word; he called it 'betrayal.'"

"Julie was simpler about it. She just said, 'They were jealous.' All I knew was, I was uncomfortable. There was anger in their voices. But you know, here's the curious thing: We could show up at a soundcheck in Davenport, Iowa, and start to play Born On The Bayou, and we'd be awesome. It sounded just like the record. But I could show up at a rehearsal place with two new songs - 'Hey, I've got a new song, Lodi.' Or 'Let's learn this one, it called Green River' - and in minutes we sounded like the rank, Top 40 band we were a year earlier when we played some club on the outskirts of Sacramento. It was clumsy. There was no understanding of how it had to go.

"Piece by piece, I would show everybody what to play so that the things could rock out. It's kind of like a hitting coach to a team. The batter can hit the ball, but you have to show him the film - 'That's wrong. Do it this way.' When we got the cylinders running smoothly, it all worked, but it always surprised me how, whenever we had to learn something new, it was so awkward again. We would spend two weeks on two new songs for them to become recordable."

Which is pretty amazing when you consider how much music the band put out in such a short period of time.

"I was quite a taskmaster with the band. But I was also hard on myself. I looked at all the stuff and realized that I wasn't getting any help. Like I said before, 'God, I guess I'm gonna have to do it with music.' I pushed myself like a mad scientist - writing, writing, writing, every single night. I'd be up to four AM working on inspirations and arrangements. And I was always trying to stay one step ahead: 'Here's another new song. We have to learn this 'cause in six weeks we have to record it.'

"I look back at it now, and I'm kind of in awe. When I was 23 or 24, I had a wife and an infant, but the whole time I was doing music. I was doing it as if my life depended on it - with a vengeance."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I’m drawn to melody and drama - AOR and yacht rock”: Tobias Forge says the new Ghost album combines smooth ’80s sounds with Black Sabbath-inspired lyrics

"The demo had my singing on it. When I played it to the band, the look on their faces said, 'We’re in trouble, boys'": Mike Rutherford and producer Chris Neil remember the making of Mike & The Mechanics' All I Need Is A Miracle