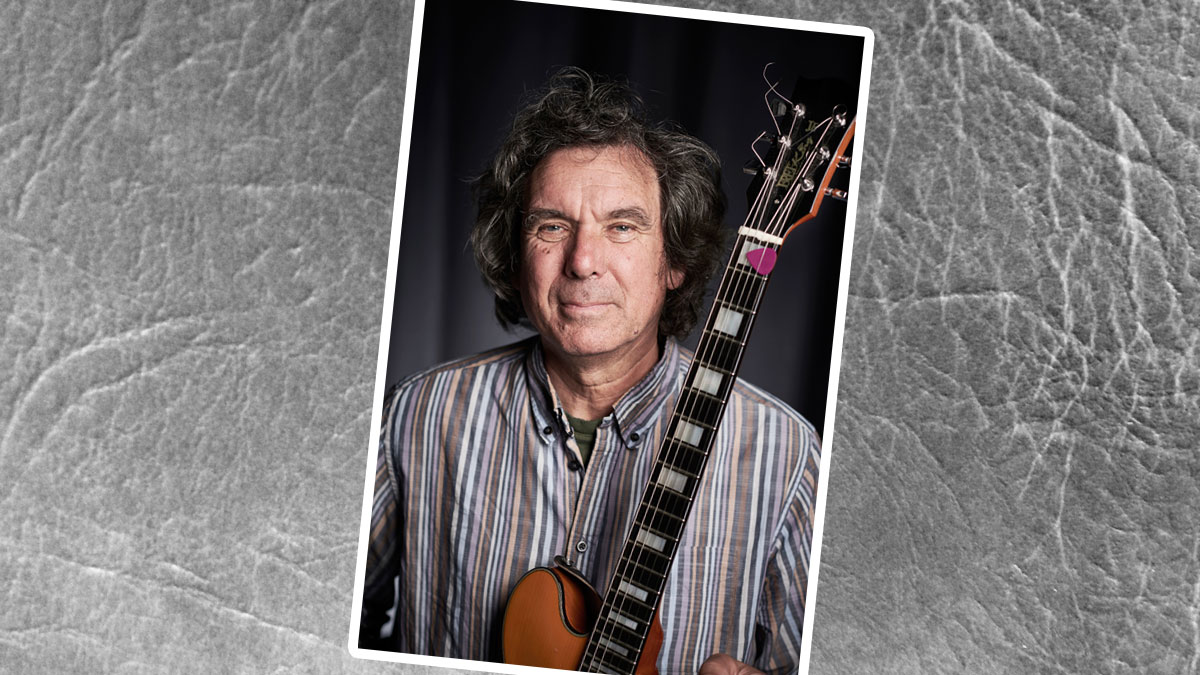

John Etheridge talks Soft Machine and London's 60s six-string scene

The jazz-rock luminary remembers his roots

Introduction

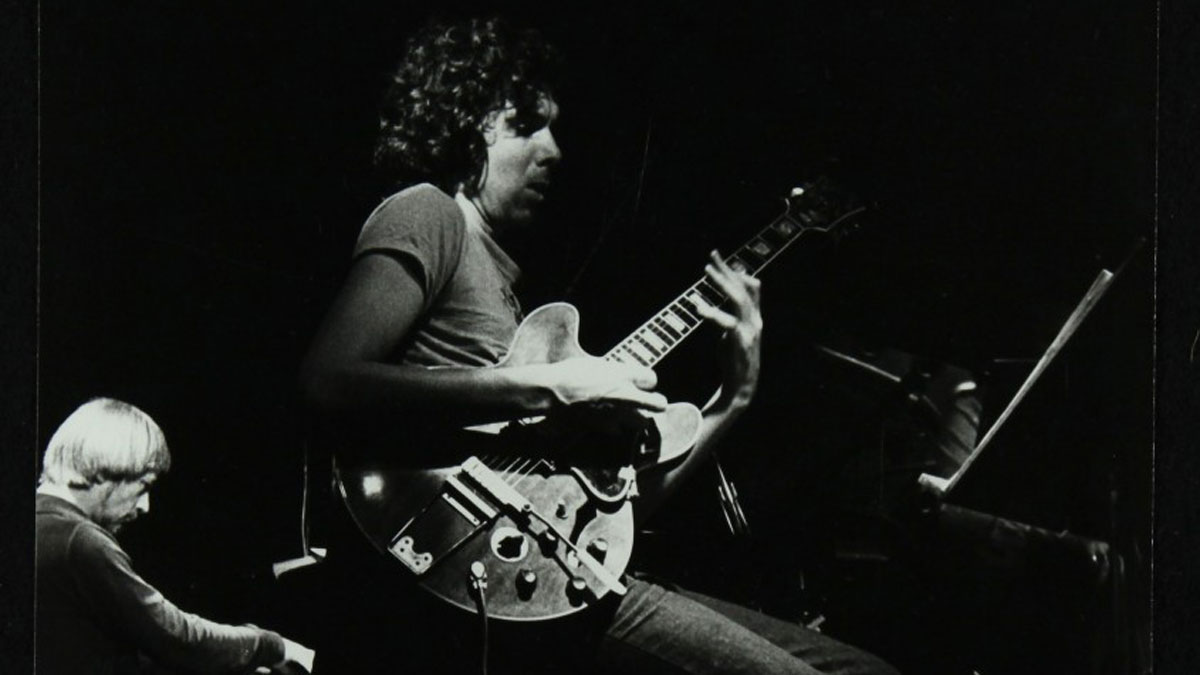

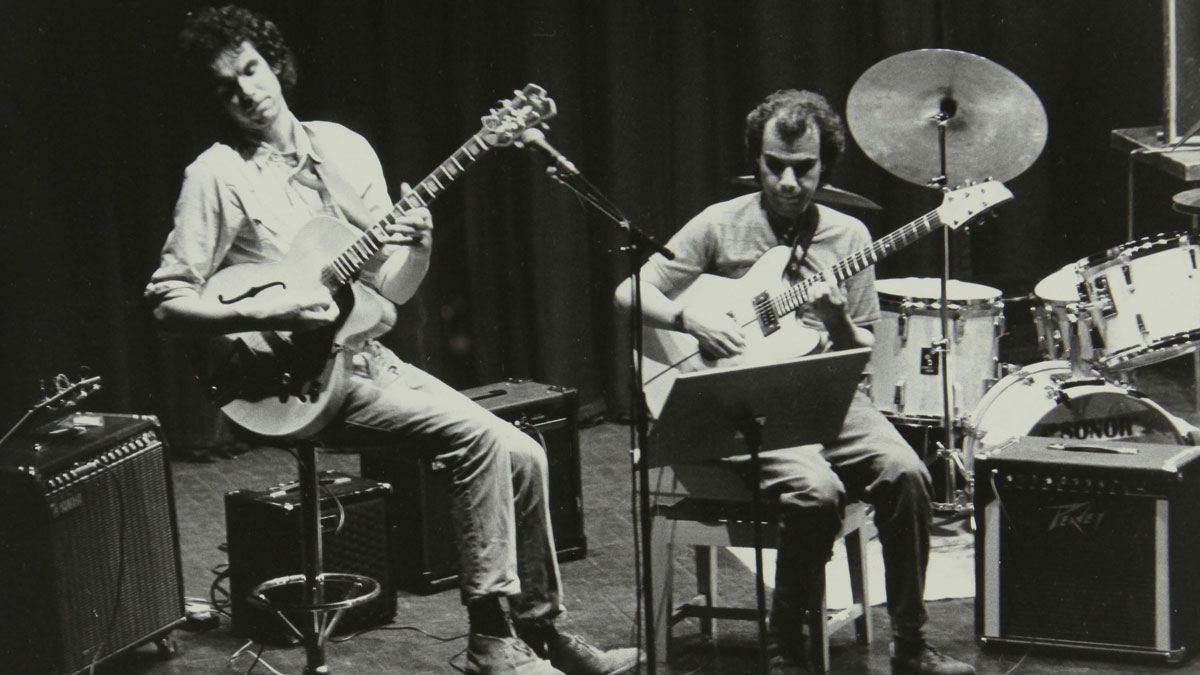

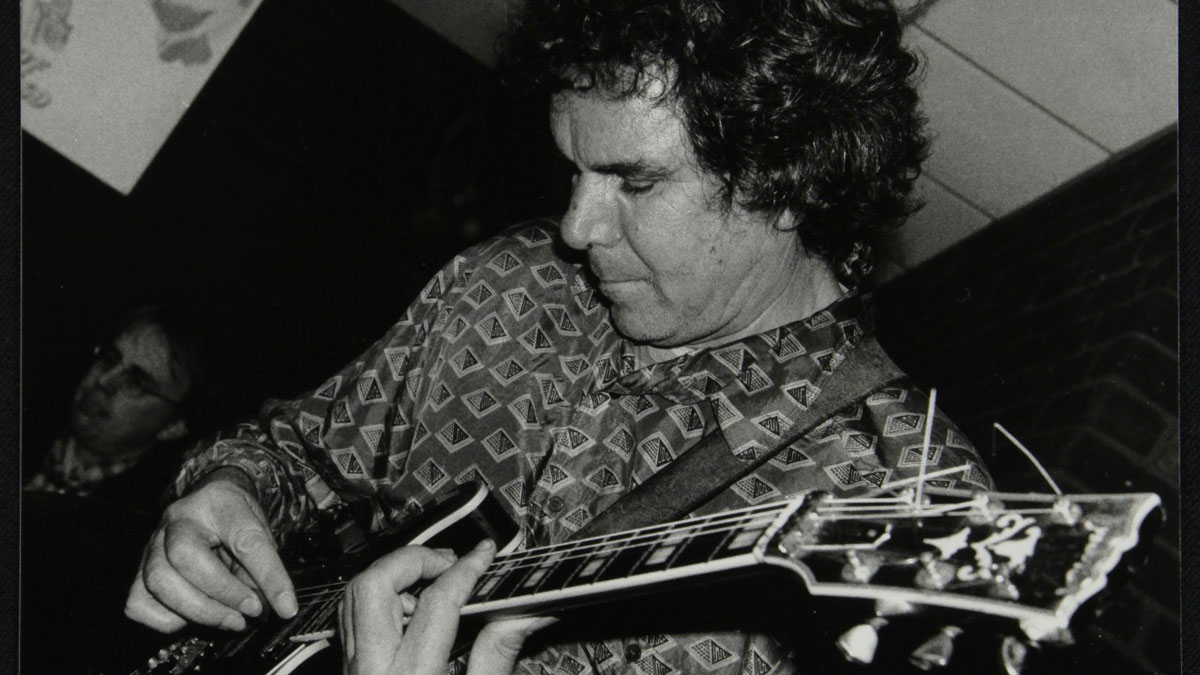

John Etheridge’s musical path has taken him all over the world with the likes of Stéphane Grappelli, classical maestro John Williams and the group with whom he’s most famously associated, jazz-rock pioneers Soft Machine.

Equally at home on acoustic, solidbody and archtop electric, and just about everything in between, John Etheridge has been involved with some of the world’s finest musicians over his 45-year career.

Stylistically, he’s played the lot - including solo jazz, fusion, gypsy and even touching on world music on occasion - and to have such a vast range of styles available to him, his influences have to be pretty diverse, too. We sat down with him and asked him how it all started…

Is it true The Shadows were your first musical influence?

I’d been playing about five years, was an okay guitarist and had heard some great players, but Eric was something else entirely

“No, they were my first inspiration; my first influence was Django Reinhardt. In my first band, the rhythm guitarist’s dad heard the rubbish we were playing and said, ‘Have a listen to this bloke Django.’

“On every level I went, ‘What?!’ I was totally knocked out with the rhythm, his insane chromatic runs that still sound amazing. My dad didn’t like it, he preferred Charlie Christian. I remember him saying, ‘We used to hear Django in the 30s. We thought it was novelty music!’

“The blues boom was just starting, too, so I heard Buddy Guy and others, but when I finally went to college, a mate talked about this bloke Eric Clapton. I knew The Yardbirds stuff and thought he was good, but my friend took me to The Manor House to see Eric. At the time he’d just joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.”

So, this would’ve been 1965, then?

“November ’65, before the ‘Beano’ album. There he was with a Les Paul/Marshall setup and I was completely blown away. I’d been playing about five years, was an okay guitarist and had heard some great players, but this was something else entirely, just totally unbelievable.”

The gig that changed it all

It sounds as though that gig had a massive impact on you…

“Oh, that was it - we were all in tears. This gets forgotten, but at the time, it was something that hadn’t even been conceived of. No-one was doing anything like it. Of course, we now know where Eric’s inspiration came from, but this was something new: the sound and the place he’d taken it to was unique.

Whatever people say now, he was the first guy to use overdriven guitar. That whole ‘Clapton Is God’ thing was really true

“Check out the live version of Stormy Monday and remember he was only about 20 or 21 years old. It was like it was from another planet - it was just stratospheric.”

Why was it so different?

“In a way, it was like a lucky accident. You’ve got these brand-new Marshall amps, which very few people had back then. It’s only 30 watts, so he’s turned it up full and then he’s got the Les Paul, which - people forget - nobody wanted back then; it was a failure and had been discontinued by the time Eric got his.

“Suddenly, he’s got this sound. Whatever people say now, he was the first guy to use overdriven guitar. That whole ‘Clapton Is God’ thing was really true. Within a year, everybody had a Gibson Les Paul and was ripping Eric off.”

Hendrix handover

Did you get to see Hendrix in the clubs around London?

“Yes, his whole thing was so balletic. The way he would play and conduct himself, it all flowed so beautifully - quite unbelievable. Of course, Jimi’s arrival freaked Eric out somewhat, because Jimi kind of replaced him as the king.”

That’s ironic: Jimi’s motivation for coming to England was to meet Eric…

The genius in both Hendrix and Clapton was a short-lived thing. That’s not to downplay them, I think that’s true of anyone. It doesn’t last and most of us get nowhere near it in the first place

“And the first thing he did was get a Marshall amp! Both Eric and Jimi were geniuses. I believe that great players keep their talent, if they have it, but genius is something that flashes through someone and then it’s gone.

“Everyone says of Jimi, ‘Oh, what he could have done if he’d lived…’, but I think they’d see him like they see Eric - a great player who survived. The genius in both of them was a short-lived thing. That’s not to downplay them, I think that’s true of anyone. It doesn’t last and most of us get nowhere near it in the first place.”

What about the jazz players coming up in the 60s? Wes, George Benson, Joe Pass?

“A major thing for me was hearing the Joe Pass album called For Django. I listened to it constantly for about five years. To me, it’s the best straight-ahead bebop jazz-guitar album ever. I couldn’t get enough of it and learnt all the solos by ear. Again, it was a flash of genius.

“The next big moment for me was hearing John McLaughlin’s album Extrapolation in 1969. It’s an amazing album. McLaughlin’s playing on it has such a force to it - fantastic.”

The big Mac

Isn’t it incredible that guitar-based music went from Marvin to McLaughlin in the space of eight or nine years?

“I think that’s partly because guitarists then didn’t have much access to the past. Guitarists couldn’t learn a solo by slowing it down or watching the internet or whatever. They just got on with it and made the music they could under the circumstances. There was a real explosion as a result.

None of us were schooled properly and all developed weird ways of playing through a combination of watching players at gigs and interpreting little bits

“They were bound to come up with something fresh as they would have little fragments of lots of things floating around rather than the luxury of studying one person or piece of music. I think that’s why so much original and exciting music comes from that period.

“It’s similar with technique. None of us were schooled properly and all developed weird ways of playing through a combination of watching players at gigs and interpreting little bits we’d picked up from records.

‘The way that musicians are trained these days is great for them, because they learn all aspects of negotiating any chord progression and correct technique, but it’s not so good for individuality.”

So, here we are, into the early 1970s and, as a player, you’re in the vanguard of a new rock-flavoured jazz movement, which leads us on to Soft Machine…

“It was 1975 and Allan Holdsworth had just left and passed them my number. I’d been with [ex-Curved Air] Darryl Way for a few years and Chris Welch from the Melody Maker was really into my playing, so I’d been getting a bit of attention and was offered the gig.

“They’d auditioned all the jazz guys on the scene but they weren’t right. It needed someone coming to jazz from a rock perspective, not the other way round. It was pretty hard work at the beginning, though.

“We were promoting the album Holdsworth had recorded and it had these endless guitar solos; it took me a while to get into it.”

Making the 'Machine

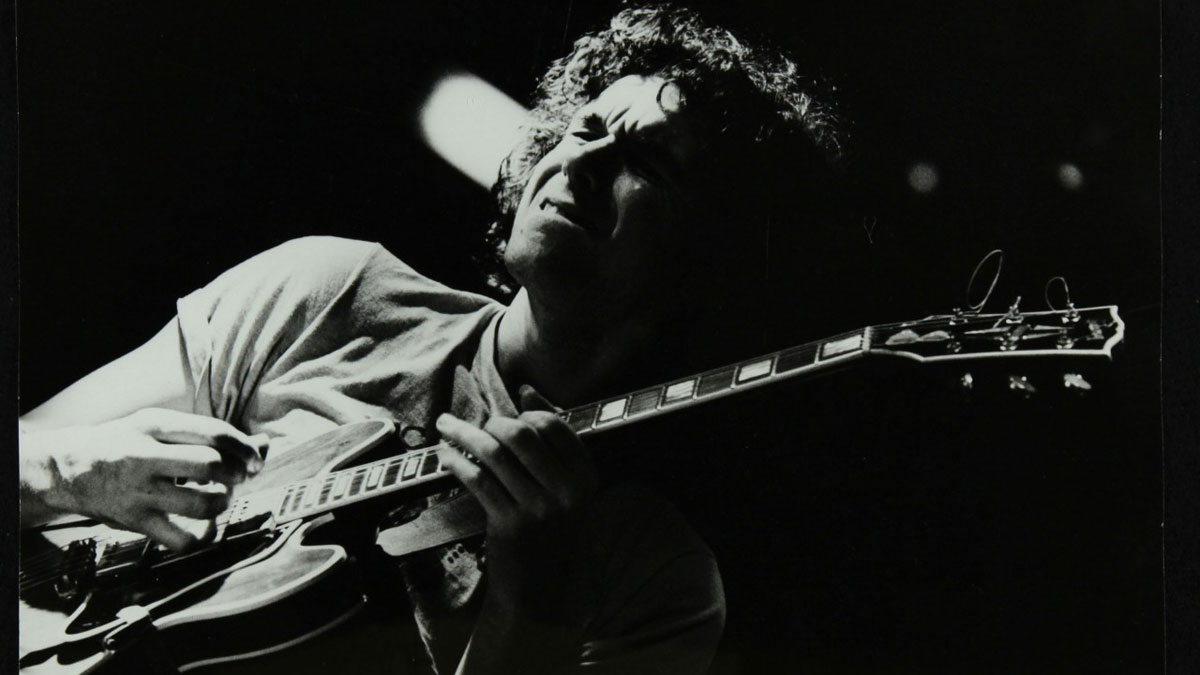

Do you recall what your gear setup was in the Soft Machine days?

“By then, I’d got my Gibson SG Custom - a great guitar I could really fly around on. I used a Marshall 50-watt head and a 4x12 cabinet. That was simply because it was the ‘band amp’ - I inherited it. I plugged straight in, no pedals, although by the time of the album Alive & Well, I’d got an MXR overdrive pedal that I used as a boost for solos.

Grappelli’s music is nothing like Soft Machine, but Pete Shade was raving about me, so Diz called

“Effects were frowned upon in Soft Machine - you were supposed to get your sound with just guitar-lead-amp. The Marshalls didn’t have reverb then, either.

“On stage, I would screen the amp off so I could hear, and play off the drums more. Being able to hear less of myself really helped me dig in and play. I always felt that I could play with more intensity if I couldn’t hear myself so well.”

So, with you being at the forefront of the jazz-rock scene, how did you end up with Stéphane Grappelli?

“Diz Disley was with Stéphane at that time. He bumped into my mate Pete Shade [jazz vibraphonist] on the street one day. Stéphane was looking for a replacement for Ike Isaacs and Pete told Diz about me as he’d just seen me on the TV with Soft Machine.

“Of course, Grappelli’s music is nothing like Soft Machine, but Pete was raving about me, so Diz called. I didn’t even have an acoustic guitar then, so I borrowed one.

“Diz had an original Maccaferri. We went to Hamburg to meet Stéphane and, after a few tunes, he said, ‘Yes, I like that fast business - it amuses the tourists!’.”

Django-go

Did you feel you were having step into Django’s shoes in that band?

“No, not at all; that worked in my favour. The last thing Stéphane wanted was a Django-style player; he wanted to hear new things. For example, it was the late 70s and that whole quartal voicing thing was happening, which, although he didn’t play that way, he loved.

I remember Les Paul came backstage and was chatting away. Stéphane turned to me and said, ‘Who is this guy?’ - he was a very funny man

“He encouraged me to play the way I wanted to, which was lovely. Having said that, he was very proud of his association with Django. Every guitarist wanted to work with Stéphane.

“I remember, in New York, Les Paul came backstage and was chatting away then came and sat in, unannounced, on the gig. Stéphane turned to me and said, ‘Who is this guy?’ - he was a very funny man.”

Your career then took another eclectic turn when you began working in a duet with classical legend John Williams…

“John lived near me and was thinking of doing something with another guitarist, so he suggested we get together and have a play. Actually, originally it was a quartet with bass and drums playing African music. I found that very hard, because there’s little to do but it has to be spot on, rhythmically.

“Anyway, after a while, it got whittled down to a duo; we commissioned some new pieces and had a solo spot in each show, too. Of course, John just sight-reads anything that’s put in front of him - talk about not being in your comfort zone!

“We did a live album once with no separation at a guitar festival, with people like Paco Peña in the audience. It came out great, but it was terrifying. Ultimately, it works well: we both play to our strengths. John has the most phenomenal technique; it’s absolutely perfect with the minimum of effort.”

Keeping busy

What keeps you busy these days?

“I’m recording right now with a great singer, Vimala Rowe, and I continue to work with the Soft Machine Legacy, which is a mix of players from different periods in the band’s history.

Every guitarist has a different physical technique, so don’t worry about that ahead of the music.

“We’ve made a lot of albums with that group. John Williams is semiretired, but we still do concerts together. I also do a lot of solo-guitar gigs, which I love. I have a group called Sweet Chorus, a tribute to Stéphane of sorts. Actually, last year, I toured with Hawkwind.”

You’ve had a busy and varied 45-year career to date. Any advice?

“First, you should find an instrument that complements you and lets you play naturally. The difficulty today is that there’s so much information on so many areas of playing. If you don’t look out, you’re going to get bogged down.

“I think it’s about finding a musical area that really appeals to you and going with it. Every guitarist has a different physical technique, so don’t worry about that ahead of the music.

“On paper, Wes Montgomery, Django Reinhardt, Pat Metheny and tons of others have a technique that’s ‘incorrect’. Metheny’s a great example of someone whose technique looks odd, but listen to him - he’s fantastic.

“We didn’t worry about correct technique when we were growing up, we just played!”

For more information on John Etheridge and the Soft Machine Legacy, visit the website www.johnetheridge.com