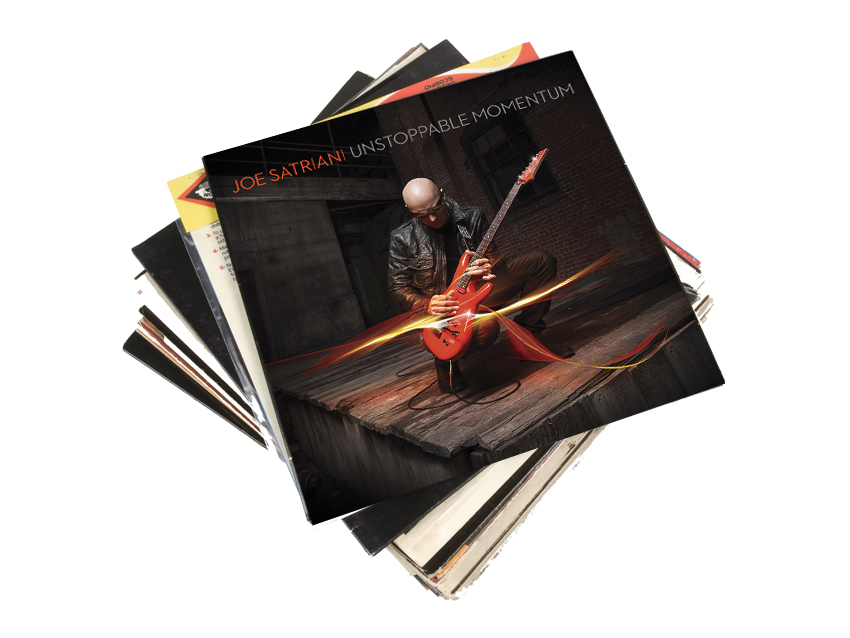

Joe Satriani on Unstoppable Momentum track-by-track

Joe Satriani writes a lot of riffs. Some become songs, a few even become stone-cold classics, but the majority of them get tucked away, hoping for their day in the sun. Late last year, the guitarist came up with a twisty, hooky chord pattern that sounded so unbelievably right to him, and it happened so spontaneously, that he knew it couldn't be contained.

"All at once, the riff just consumed me," Satriani says. "I played it over and over again. I wanted to play it 100 times a day. It felt good, it sounded good, it looked good on the guitar – all the things you want a riff to be. I had visceral, spiritual and intellectual reactions to it all at the same time."

As soon as Satriani completed sketching out the rest of the song, a simple yet bold phrase entered his thoughts that seemed to express everything he was feeling: unstoppable momentum. "The words fit the song, but then I realized that they meant so much more," he says. "They applied to the rest of the album, the album that was going to be. Forward motion, unlimited potential – that kind of vibe just carries you away."

The 11 songs that appear on Unstoppable Momentum, culled from upwards of 60 musical ideas in various forms of completion, cover considerable, and even surprising, sonic and emotional ground. More so than ever before, however, a pronounced, sustained feeling of buoyancy informs the set, even on songs that are dead serious.

"I had to be brave enough to be lighthearted," Satriani notes. "But how do you do that and still be heavy? The Beatles did it. Lennon and McCartney were so good at that. Beck is the same way. Some artists have a way of being entertaining while dropping something heavy on you. They make the weight available to you, and if you want to find it, it’s there. Exploring that is pretty interesting."

Earlier this year, Satriani returned to one of his favorite studios, Skywalker Sound in Lucas Valley, California, to record the new album. With him were a couple of trusted colleagues from past projects, co-producer and engineer Mike Fraser and versatile keyboardist Mike Keneally, along with a couple of wild cards: Jane's Addiction bassist Chris Chaney and drumming icon Vinnie Colaiuta.

Despite the players’ impeccable credentials and acclaim – this is especially true for Colaiuta, the recipient of hosannas and huzzahs from every drummer on the planet – Satriani admits that he had no idea how the whole thing would pan out. "It’s always a guessing game," he says. "What makes a band work well together can be a real mystery. But you just have to trust a feeling that everybody is going to play off of one another, and it's going to click."

Not only was Satriani elated at the musicians' chemistry with one another, but he was particularly struck by their response to his material. "Everybody was approaching the songs in very inspiring and interesting ways," he recalls, "which let me settle back and not have to tell people what to play. Every time we did a take, everybody would play something different, and I would say, ‘Wow, that was really great!’ Seeing them so inspired rubbed off on me, and I became more excited as we went along."

Unstoppable Momentum will be released on 7 May. You can pre-order the album at this link. On the following pages, Satriani talks in-depth about the writing and recording of all 11 tracks.

Unstoppable Momentum

“As soon as I started playing the riff, it put music to a feeling I had in my chest about being so excited to create something. It was a physical sensation in anticipation of moving forward; I didn’t know what I was doing, but I had no doubt that it was going to be incredible.

“The joy and giddiness I felt were impossible to contain; the emotions couldn’t be stopped. It was as if a huge, 200-story ball of something was coming right at me. I could either jump on that thing or let it crush me. My attitude was, ‘I’m jumping on and going for a ride!’

“A lot of times, when people are overwhelmed by something rolling towards them, it tends to be destructive. But I thought, ‘What if this thing sailing at me creates nothing but great stuff? Opportunity, happiness, fun, love – everything you could want.’ I kept that in my mind as I was propelled into writing the rest of the song.

“Recording it in the studio was sheer bliss. The take we used was number six or seven. By the time we played it, I hadn’t really defined the outro yet, so I got on the talkback mic, which I could use as we were playing together, and I said, ‘Why don’t we keep it going? And Vinnie, maybe you can kind of freak out and keep playing the line.’

“What happened was, everybody played the whole song differently, and Vinnie went totally crazy at the end. As the song finished, as the cymbal died down, I screamed, ‘That was fucking awesome!’ That line didn’t make it in – sorry.

“When I planned my guitar solo, I was thinking of something more ethereal sounding. Sitting down to actually record it, I wasn’t moved in quite the same way. I used one of my JS guitars with a Sustainiac, and I went for total guts on it, nothing but teeth and gnarliness. [Laughs]

“I did a thing I call ‘the meat cleaver,’ which is actually something I taught Chad Smith in one of our videos. He wanted to learn something on the guitar, so I showed him just the most ridiculously useless thing ever [laughs]. And there it was – I was in the studio, and I was doing ‘the meat cleaver.’ So I guess it wasn’t so useless after all.”

Can't Go Back

“This is a piece of music that I wrote right after Carter [Chickenfoot co-manager] had passed away. I had it on the back burner but hadn’t really thought about it. When I was in the middle of demos for the album, I found that I suddenly kept coming back to it. I told myself, ‘You’ve really got to call it something… ‘ But what?

“I think I was trying to disassociate myself from how the song came about, but I kept thinking there was something cool about it. I started to think about the book You Can’t Go Home Again [by Thomas Wolfe], and I re-channeled my feelings about the song more towards that kind of idea – how difficult it is, once you’ve grown, to return to your home base and see it and experience it in the same way.

“Once I got to this point, I was free to explore the melody, and that was a really good day. It was so clear, so articulate, the way it came to me. I played the melody one time, and there it was. It was a real musical moment that I had to keep.

“One of the things I talked to Mike Fraser about on this song was that I wanted to use guitars as background singers. The melody I'm playing is one thing, but there are these answer guitars that really deliver and explain the message of the lead singer. It’s crystallized in those little bits. There’s a lot of rhythm information that’s going on that is gorgeous to listen to.

“It’s a reflective song in that you’re telling yourself you can’t go back, yet you’re always going back. We face the future by examining the past, but we also take that next step by saying, ‘We must go forward.’”

Lies And Truths

“The song is about how you deal with people who are lying to you – what are lies and what are truths, both in the world and on a personal level. That’s why the song has a night and day aspect to it: the chorus is more uplifting with a little bit of melancholy – it’s the truth side – but the verse is disjointed and rough, because that represents the lies.

“I played a neat little experiment on everybody with this song. I could seed the environment of the tracking sessions by revealing certain song titles but not all of them. The working title of this one was ‘Fast Robot.’ It had nothing to do with what the song is about, but I think it had something to do with the original demo’s Pro Tools file that I had built upon.

“I thought it would be funny if I played the song for somebody and they looked at the title ‘Fast Robot’ – they would have a certain feeling about what to expect musically from those words. So I decided that I wasn’t going to tell people that the song is called Lies And Truths until we’ve arrived at some particular spot.

“So we’re making the record, and on the morning we were to cut this song, Vinnie showed up, sat down and arranged his drums, adjusted cymbals, and while he did this he listened to the demo to get his ideas down. He not laboring over it; he’s just vibing and getting into it, getting ready to play. But he sees that it’s called Fast Robot, and he starts playing like that. At the end, he was playing like a robot gone haywire. Inside, I’m saying, ‘This is working. This is great.’

“Everybody was playing in a certain way, except for Mike Keneally, who has this weird, Jedi-like ability to read into my inner psyche and figure out what the song is really all about. When the guys read about this, they’ll probably say, ‘Damn, that Satriani!’” [Laughs]

“In one part, I play a thing on the guitar that harkens to the days when I did a lot of tapping on the neck. I like using the edge of the pick – it sounds a bit like icicles. Because of the key we were working in, I had to go up really high. I had my JS2400, so I could go all the way up to the 24th fret. I was using a SansAmp, so I was just monitoring it through Pro Tools – the guitar was DI. When I sat back and listened to it, I was like, ‘Whoa… that’s the part!’ It turned into this really beautiful centerpoint.”

Three Sheets To The Wind

“This is a piece of music that I wrote when I was working on a new guitar for Ibanez, one that’s very Stratocaster-like. I was having a ‘Texas moment; I was in a very Eric Johnson frame of mind, where I had this beautiful tone through a little Fender amp. I wrote this melody, and I thought it was pretty cool as a little guitar piece. I didn’t think anything of it until I realized that I was walking around humming the melody.

“I sat down to really look at it as a full-on melodic statement, and I thought it was great, but I also said, ‘I’ve got to get rid of the way it was written.’ It shouldn’t be on the guitar like that. It’s been done. Eric’s said that kind of thing beautifully. If I was going to do this, it had to be very different.

“There were weeks where I played the song on every conceivable instrument, trying to figure out if the melody survived on piano, on a B3 or farmed out to several guitars. I was like, ‘Is it an acoustic song? Should it be distorted? Should it go back to the Strat-y/Tele-caster-like thing?’ Somewhere along the line, I came up with the idea of a horn section.

“I had Kontakt 4 up, and I took a journey through a horn section – not quite New Orleans, not quite Tower Of Power, but it was some new kind of a thing. I worked on it as an intro piece. Now, the song that it went into was something I hit a million different ways. Two months later, I came up with the idea of the Sustainer playing the melody with the honky-tonk piano. I did an arrangement where that starts the song, and then the band comes in, but there’s only one verse; there’s only one time with that Stevie Ray Vaughan-type melody.

“For the rest of the song, it goes into this other journey, because I realized that what I was thinking about was this guy who’s dressed up in a hat and tails; he’s had a few cocktails, he wanders out of his urban apartment, he gets into a lot of trouble, but he winds up unscathed. He ends the night by sipping a glass of champagne. There’s a real story going on, and that’s why you hear noise effects, sirens, wah-wah guitars, all kinds of stuff. Suddenly, it vanishes, the horns come back in, and the song gets a little tipsy again.

“It’s a very cinematic piece, but it started out so simply. I kept it in my mind that it had a bit of a Sgt. Pepper album aspect to it: an orchestra, backwards stuff, an acoustic guitar, an electric guitar, horns, honky tonk piano, Texas blues – there’s a lot going on.”

I'll Put A Stone On Your Cairn

“It was difficult to find a title for this song. Although it was deeply moving to write, at the same time, I had to recognize it as being part of myself. It’s like when you draw something in your sketchpad, and somebody looks over your shoulder and says, ‘Why did you draw that?’ You examine what you did and figure out where it came from.

“The process of writing it was all about realizing there was a part of me that needed to prepare for a farewell, but then it shifted to wanting to stay very positive. How do you celebrate the contribution of life while acknowledging that, although it’s certainly an ending, it’s also about the memory that you’re going to carry around with you?

“I had all kinds of titles – Farewell, Goodbye – but it was all too negative. I wasn’t able to connect with the right word or words. Then I came across something about the pile of stones as a marker, and I thought, ‘Yes, that explains it.’

“The piece was done innocently. I improvised it on keyboards, and then I sat back and listened to it and said, ‘Wow, what is that?’ Because it started with this Beatleseque organ, so it was very drifting and full of attitude. I picked up the guitar – and it was the first thing I think I ever recorded with the Sustainiac – and it just took off. I turned the volume on the guitar down and tried to get a more subtle tone. Then it was like, ‘Whoa! Where did this come from?’

“It felt so real, the recording, but I thought it needed some type of orchestra. I wanted something different, though, and so I focused on the trumpet, trombone, English horn, French horn. The song was getting closer to what I was describing in my head. I wanted the music to make people feel good; it shouldn’t be a bummer. If anything, it’s supposed to be a celebration.”

A Door Into Summer

“The title came from Robert Heinlein’s wife – Robert’s a great science fiction writer. As the story goes, his wife was complaining about a bitter winter, and she said, ‘I wish there were a door into summer.’ He wrote a book with that title, although it was about something else altogether. Being a big reader of science fiction, I thought it sounded cool.

“It’s funny, because Summer Song was going to be called A Door Into Summer, but I changed it. For some reason, I thought at the time that it was just too much. Also, I remember riding with one of the promo guys for Relativity, and he said, ‘If I could just have that one summer song... ' That stuck in my head. I was reminded of the original title when John Cuniberti and I were doing this massive remastering of my catalogue. There it was on these boxes of tapes: A Door Into Summer. I remember writing it years ago, thinking about that very first day of summer.

“I brought the song to Chickenfoot a while back. I thought it would allow me to chug more on the rhythm, setting Sam free in a lyrical sense so he could really talk about a story. But it just didn’t click, and I tucked it back in my pocket. I knew I had to figure out parts of the puzzle, and a big chunk of that was taking the rhythm guitar and making four versions of it.

“If you listen carefully, there isn’t just one riff; there’s three ways of playing it, and they’re kind of going all at the same time. In that way, I avoided sounding like certain songs that were inspirational – there’s a bunch of Van Halen songs where Eddie led the band with one big rhythm guitar. He writes great, heavy riffs and really pulls that who thing off. David Bowie’s Rebel Rebel, too, which is a two-chord song as opposed to this, a three-chord number.

“So I’ve got three positions and three different voicings, which wound up making the whole thing bigger and gave more freedom to everybody else in the band to move around. Summer Song was more rigid in that I got locked into meticulous double-tracking of left and right guitars. This one had to be more relaxed, expressive and open. That was the simplest part of it; the hardest aspect was the fact that the song is so lyrical; there’s so much melody guitar.

“I was bearing down on my hyper-melodic trip. That’s what this whole record is about – these nice long melodies that develop, not short little things. On the flipside of it, because I had a super-long, lyrical verse and a very long chorus, and there’s no harmony anywhere, the solo had to be light and playful. Over the verse patter, I decided to just go super-expressive all over the neck. That allowed the rhythm guitars to lie back a little bit and be kind of undisciplined.

“I like how lightly Vinnie plays, especially on this song, but he also plays with such weight and meaning – it’s a neat trick. A lot of us have chased after the Bonham thing – ‘Bonhamesque this’ and ‘Bonhamesque that’ – and that’s cool. But Vinnie goes for interpreting the song in his own compositional sense; we didn’t lock him in with any kind of restrictions or directions. We just waited to see what he’d come up with, and we were always thrilled.”

Shine On American Dreamer

“It was one of those moments when I was down in my studio playing this riff, and the whole song kind of unfolded in my head. I was thinking of the tragedy here in America over the last decade and what greed and stupidity have done to generations of families, in both their ability to make a living and build a life.

“Leading up to writing this song, I must have read 10 books on the economic collapse and how everything led to the crash of 2008. I really developed a historical view of situation and how it went back several administrations; how the lessening of control over Wall Street opened a Pandora’s Box of greed.

“And it’s not fair. It’s not fair to families who are leading good lives, raising families and living the American life, only to get undone by this small group of people who will do anything to make a little more money. This needs to be rescued; it needs to be fixed. The American dream, which is a work in progress, has to be re-dreamt every day. We’re still a young country, but we have to be tweaked, and we have to constantly look out for the nasty elements that are dragging us down.

“I know that’s really heavy, and obviously, I didn’t want the song to be this crushing weight. It turned out to be pretty upbeat and relentless, just powering along. The chorus is this ascending thing with these big chords, and it has a bit of a heartland vibe to it. The verse is quite dreamy. I always say it’s very ‘Joe’-like – a little rough around the edges, not quite defined, and it leans a lot on the delays. If I could only have that in my daily life – a huge digital delay! [Laughs]

“The ride-out is very minimalist. I always think that a guy doing a guitar record would be compelled to solo all the time. But we’re just playing the riff, and there’s power in that. It’s what the song needed, just this big killer riff driving it home.”

Jumpin' In

“The song comes in two parts. I conceived it that way, but then I forgot about it. One day I had a creative spurt, and it was all about swingin’. I was enthralled with the idea of a guitarist being the saxophone player in a big band, where a guy stands up with the tenor sax and leads everybody with a head, just like in Satch Boogie.

“As I was playing with the riff, I knew I wanted to present both lighter and darker sides to it, along with some rhythmic shifts. I decided that I wasn’t going to make it about a deep subject that you have to consider as you make your way through the song. It was going to be a musical celebration.

“I had a great time with parts, starting out with this countrified thing into a half-time/double-time thing, and then suddenly it breaks down into a dreamy bit, which then goes into a funky thing – it’s a lot! When the song ends, it kind of wipes your memory clean of how the song started. It’s like a dream that comes to a dramatic finish.”

Jumpin' Out

“It’s wacky and out-there. I was working on the crazy ending for Jumpin’ In, having a great time and thinking that I could do a whole album like it, and then I was looking at the file and I thought, ‘Wait a minute… What’s this?’ There was a title that said, ‘A Harmonic Minor,’ which turned out to be wrong. But as I listened to it, I thought, ‘Wow, that’s even crazier than Jumpin’ In.’

“We ended up using the guitar that I recorded at home for the main part, which is like a tenor sax part, and the end solos were done live. The two songs then made sense together because they both work off of that swingin’ guitar idea.

“In my mind, they're very similar in that they’re all about jumping on a beat. The first one makes you go, ‘Holy shit, what did I just listen to?’ And then you have to go back to the beginning to figure it out. I really like that.”

The Weight Of The World

“There were a couple of songs that were written in the kitchen. I was having some work done downstairs, and it was loud and annoying, so I sat at the kitchen table with my guitar and played around with some things. I came up with an interesting bit, and then once everybody had left, I went downstairs and checked it out. I thought, ‘Wow, can you really write a verse where it’s all chords?’

“I made the verse very stabbing rhythmically, and I think that allowed the chorus to have a bigger release. Ever since high school, I’ve had love-hate relationship with the rules of counterpoint. When you follow the rules, you get a great, beautiful, fabulous result, but you’re kind of stuck there. When you try to push things a little bit, you get a more modern result.

“A lot of the songs that I brought in had keyboards; it was just the way that I worked. I was very concerned about intonation and timing, so I thought, ‘I’m not going to start with some weird, out-of-tune guitar part and force everybody to be in tune with it.’ I wanted to begin with things that I knew would be in tune, and as I added stuff, I could see how far I could stretch intonation.

“Mike Keneally came up with really beautiful organ stuff and a gorgeous, drifting pad thing. I had on my demo these single-coil guitar chords along with a Genesis-like keyboard part that does these stabs – everything was pretty worked out. When Mike came into it, he decided to do clavinet, which we thought was pretty interesting. Vinnie’s playing was very light and dry, which we also thought was cool.

“In the end, all of this turned out to work because it allowed the solo section to completely blow up. I used the JS2400, and I went right up to the last fret. Also, I’m using the Big Bad Wah. The solo is a real release. It’s got angst and energy, and when it’s over it completely dissolves.”

A Celebration

“I had the hardest time finding a spot for this song. I kept thinking that no matter where it went on the record, you couldn’t listen to anything else after it for a while – it’s got so much energy. Also, there’s no bridge, so there’s no reflective side to it.

“Originally, the song was less than half the tempo than it is now, and it was all acoustic instruments. It started out after I purchased a Republic Resonator guitar, which I wrote two songs with. One I labeled ‘Texas’ and the other I called ‘India.’ I listened back to them and thought it would be great to combine them somehow.

“I recorded a version where I did just that, where the verse was ‘Texas’ and the chorus was ‘India,’ but they didn’t really go together. I even thought that I should call Sonny Landreth to see if he could play it; maybe it should go on his album or something.

“A while later, right around when I was finishing the demo process, my son, ZZ, had come home from school. I was cooking a family dinner – I was making lobster tails [laughs] – when it occurred to me that the song was in the wrong tempo. I also decided that there shouldn’t be a ballad on the album. So I went downstairs and did this super-uptempo version of the song, and suddenly it all made sense.

“Later on, after the dinner, we were watching a movie, Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Killer, and as I’m sitting there, my mind wanders downstairs. This scene came up in the film where they’re on the train; the train is on fire, the bridge is on fire and the vampires are attacking. ‘That’s it!’ I said. This was the confirmation I was looking for, because the train was going, ‘chug-a-chugga-chug-a-chugga,’ and the song has the same kind of thing. I took that as a direct sign from the universe that I was on the right track.

“The melodies and solos were done that day. We redid the rhythm guitars, and Vinnie came up with a new way of doing the ‘chugga-train-down-the-track’ thing. Mike Keneally left blood on the keyboards, doing a Fats Domino kind of deal, except really fast.

“There were parts that I was concerned about: Half of the solo is an ensemble. It starts out over the verse pattern, and then the descending line starts. It’s so major key, which made me kind of proud, actually: ‘Yeah, I’m playing in a major key – so what?’ I started to think that the ultimate exotic key is not exotic; it’s here, it’s home grown.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.