All Nick Drake needed was time. Before his tragic death aged 26, the preternaturally gifted singer-songwriter had yet to find his audience, his three albums having failed to capture the imagination of the early '70s public.

And yet, in the years after his death, he was to become one of the most influential English guitarists of his generation, his experimental tunings, unique chord voicings and fluid finger-picking establishing his reputation as a phenomenal talent.

Joe Boyd, his manager and the producer of his first two albums, Five Leaves Left (1969) and Bryter Layter (1970), worked extensively with the enigmatic guitarist and has recently compiled Way To Blue: The Songs Of Nick Drake, an album of live performances by artists including Vashti Bunyan, Robyn Hitchcock and Danny Thompson culled from a series of tribute concerts. We caught up with Joe to discuss recording Nick Drake and the release of Way To Blue…

How did you come to be working with Nick Drake?

Well, it was the winter of '68, '69, and the Fairport Convention bass player Ashley Hutchings actually saw him play and got his phone number and came into my office, handed me the number and said 'call this guy, he's interesting', so I did. He bought me a tape, and I put on the tape and it was pretty instantaneous - I was just stunned by the tape, it was pretty amazing, so I called him up and said let's make a record.

He was still at university when you first met right? Did you have a lot of work to do in building a set for that first album?

He was at Cambridge. He had all the songs, he had a whole album plus worth of songs. I knew we wanted to have strings, I wanted it to be a full, proper record, and I started by hiring a professional arranger. We did three tracks with him and it didn't work very well. Nick then said he had a friend at Cambridge who had arranged some of his songs already, and as Nick put it 'the arrangements aren't too bad', and that was Robert Kirby, who in fact turned out to be total genius and did these beautiful arrangements. We would do two or three songs at a time, and then sort of sit back and look at where we were with the album, have some more new ideas and then go back in and do some more. We brought in various people like Paul Harris, the pianist who was working with me on another project. He fell in love with Nick's music, and you can hear him on Time Has Told Me and Man In A Shed. And Richard Thompson played guitar. We did it little by little; we took over a year to make the record.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Was it easy to find those other players?

Yeah, they came in, you know I knew we would want a bass player and some point and of course Danny [Thompson] would be the one I would go for in any situation. He and Nick got along very well. We'd talk it through, I'd throw out an idea like having percussion on Three Hours and he's say 'oh yeah, that's good, let's have some percussion,' so I'd call up Rocky Dzidzornu and he would come in. Most of the stuff was done pretty much live in the studio. Even the string parts were not overdubs, it wasn't like you laid down a track and then overdubbed strings, you recorded in the room with strings.

Joe Boyd produced two of Nick Drake's albums, as well as acting as his manager.

That must have been quite technically difficult to do?

Well not really, not to me, that's the only way to do it! I think it sounds much better. People would comment on a track like River Man, they comment on how three dimensional it sounds, but you can't get it to sound that way unless you record it with everybody in the room, including the singers, where so many sounds are getting recorded from different angles by so many different microphones. That's the way you get those rich full sounds. If you don't have a really good engineer it can all go very sour if you try to do too much in the room at the same time, but to me that's the only way to do it, and in fact making this live record is the closest I get these days to making records the way I like to make records, because so few people are willing to do it that way. To me, it's the only way to of.

Nick Drake has a delicate voice and an intricate guitar style, was it difficult to capture that with everything else going on in the room at the same time?

Nick was the least problem, of course you mic'd him close but the point was that he never made a mistake in the studio. He never sang out of tune, he never missed a guitar note. You could really forget about monitoring him - you really monitored everybody else to make sure they didn't make mistakes, and if they did you'd stop and go back to the top, but Nick you didn't even have to bother with. And then you could have the pleasure of listening to the whole thing, including Nick, at the end.

He must have been incredibly prepared going into those early sessions.

He was very, very focussed, he practised endlessly and he had this incredible technique. His hands were huge, his hands were very strong, he was very athletic and he just played such clean parts. There's never any missed notes or blurred notes, it's just there they are, and you can hang a mix around the guitar.

How did the sessions for Five Leaves Left contrast to the Bryter Layter sessions?

Well the biggest difference is the drum kit - there's drums on mist tracks on Bryter Layter. And you know it's funny, I don't remember making that decision, making a conceptual choice, I think we started by doing something and we said well, let's have electric bass and drums on Chimes Of The City Clocks or something like that, and then once we had that and it worked and we were very happy with it, somehow we got into that mode for making that record. It seemed right to keep on doing things with a different feel. I don't think it was a conscious decision to make it more 'rock-ish' or something like that, it just seemed to work out that way.

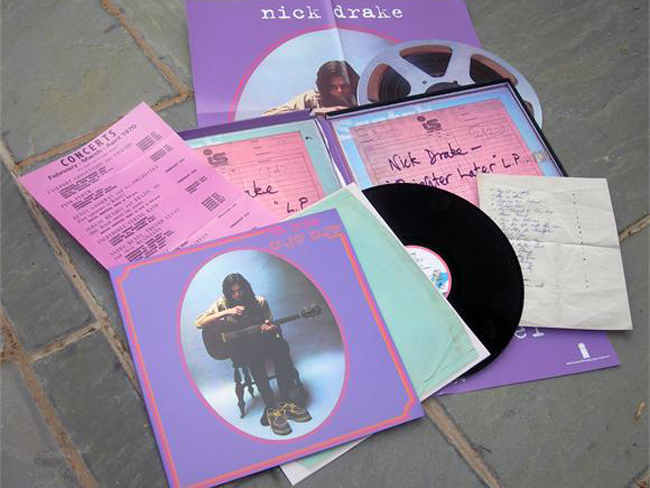

Bryter Layter has been reissued on vinyl.

Did the drums change the studio dynamic you'd established with the earlier sessions?

A little bit, not too much. At Sound Techniques there was a very good set up for the drums, there was a place with high ceilings where we had baffles around the drums. Horns and strings were overdubbed on Bryter Layter, but we didn't change it to drastically.

You often read about Nick Drake being very withdrawn - was he like that in the studio?

He was full of comments. He spoke quietly and he sometimes hesitated before speaking, but he would always make his views known, like 'I'm not sure about that take I think we'll have to do it again', something like that. And we'd do it, because we had huge respect for Nick and his taste and his vision for his music, so we would always listen to what Nick had to say.

Was he comfortable in the studio?

He loved the studio, I think he was probably happier there than most places.

As well as producing you were managing Nick as well at the time. How did that relationship work?

Well unfortunately there wasn't a great deal to be done. I think when I first started working with him he did a few gigs, I think he played at Les Cousins a couple of times and I know he played up in Cambridge a few times. The problem was that he didn't really enjoy performing, he wasn't confident or comfortable. So basically the plan such as it was, was that we'd put a record out because I felt that the only way to get an audience that would sit still and listen quietly while he tuned his guitar and never told a joke would be created by the successful release of a record.

So we did that, we put the record out and then he performed opening for Fairport Convention at the Festival Hall, and the audience there was very respectful and very quiet. He was brilliant, he got an encore, everybody loved him and it was a stunning success. So we thought ok, now we can get started here, so we booked him a small tour of small clubs, colleges, universities et cetera and nothing had changed. He still didn't have anything to say, it was really hard - people didn't come just to see him, they were there for the event or for other people on the bill, people clinked classes or talked and he lost the audiences. The record didn't sell, so our vision that the record would create the audience didn't actually happen, so the only plan B I had was to make another record. Then that didn't work, and by the time that came out he was getting more depressed.

What made now a good time to release Way To Blue?

It started with an invitation from Birmingham Town Hall to curate an evening of Nick Drake's music. He grew up near Birmingham. It worked out great. We had a great time doing it, we didn't record it - it was just one of those things, a moment that if you weren't there, you missed it. People loved it so much that we got an offer to do four more concerts the following year around England, including a London Barbican concert that the BBC filmed.

The fact that they recorded meant that I was aware they had a recording, but I thought there was not quite enough there for a record. Eventually we did some more dates in Britain and Italy, and we got invited to go to Australia and did the Sydney Opera House. Australian Broadcasting recorded more concerts in Australia, so then I had three concerts recorded properly, and I figured I'd try mixing them. I was very pleased with the results, so I played it to the artists involved and they said sure, release it, so we did. It wasn't a big plan, there wasn't a big moment where we said this is the strategy, and after three years we'll have a live record. It was more 'oh, we have a live record, let's put it out!'

What are the standout tracks for you?

Well this is a selection of really good takes I think, I pretty much like everything that's on there. To me it's most interesting when you have somebody who is very different from Nick and the song is radically altered from the way it sounds on Nick's records. I always make sure people here Black Eyed Dog by Lisa Hannigan and Time Has Told Me by Krystle Warren, because they're so different from Nick's. We were going to have two singers from Australia, and we were listening to all kinds of female voices and I don't know where I got this CD from but I stumbled across Luluc, and I just loved her voice. The Australian promoter had never heard of her, but she was terrific and that's the opening track.

Way To Blue is available now, as is a boxed vinyl reissue of Bryter Layter, which includes a copy of the original shop posters used to promote the record, a reprint of Nick Drake's handwritten set list and reproductions of the master tape reel and tape box lids.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track