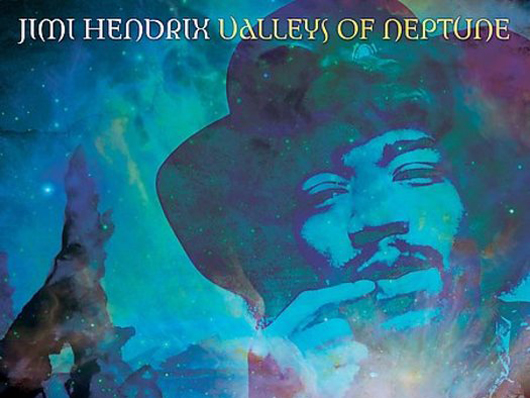

Valleys Of Neptune: intro

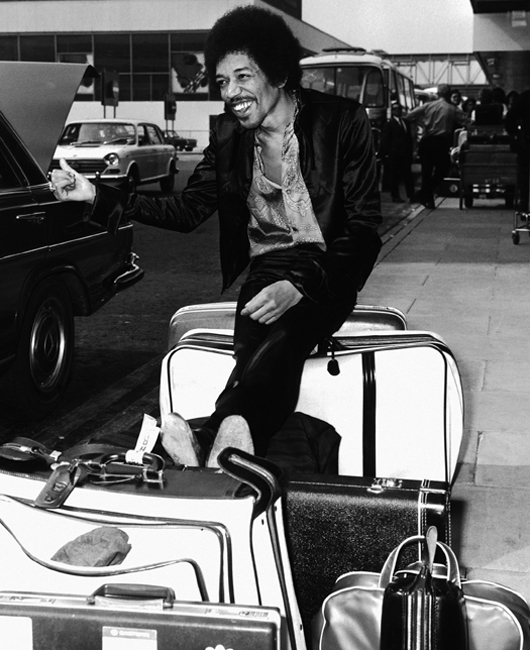

We are thrilled to review Jimi Hendrix's new album for 2010, Valleys Of Neptune. But what is especially thrilling is to come right out with the startling fact that one of the best albums of 2010 was recorded 40 years ago.

Painstakingly curated and produced by engineer/producer Eddie Kramer, John McDermott and Janie Hendrix, Valleys Of Neptune includes more than 60 minutes of music never commercially available on a Jimi Hendrix album, and it's a vital addition to the artist's astonishing catalogue.

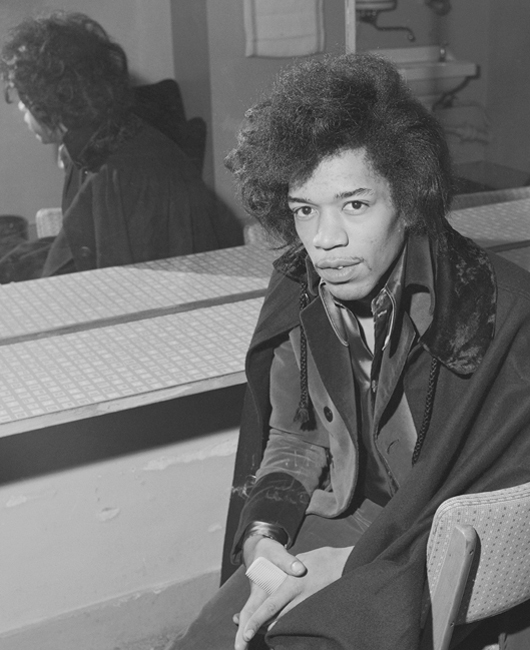

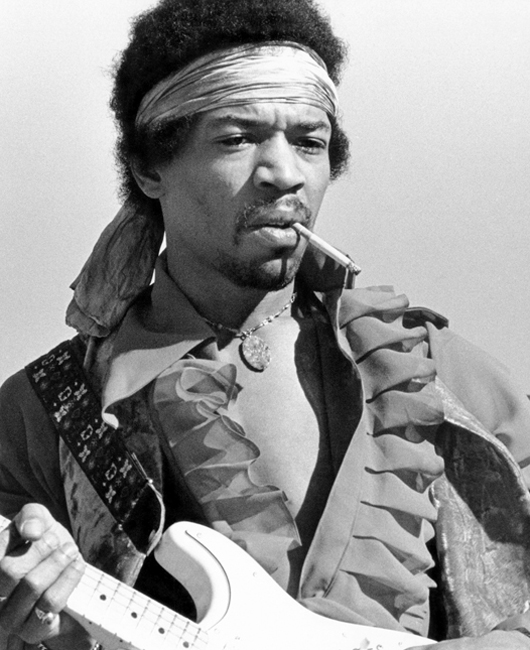

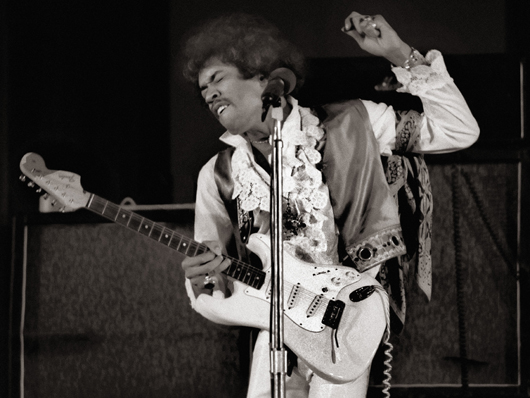

To listen to Jimi Hendrix is a sensation that never gets old. As it is in all art forms, or even sports for that matter, witnessing fantastically gifted people, wound up and at the peak of their powers and displaying feats of magic that we can only marvel at, fills the senses with all kinds of possibilities.

Hendrix was one of those such people. He caressed his guitar strings with the same flair that Picasso wielded a paintbrush, and even when his attack was intense and brutal, he had a way of making every note seem like inspired improvisation. In his hands, a guitar was a shape-shifting instrument of change, and Valleys Of Neptune proves this from beginning to end…

Stone Free

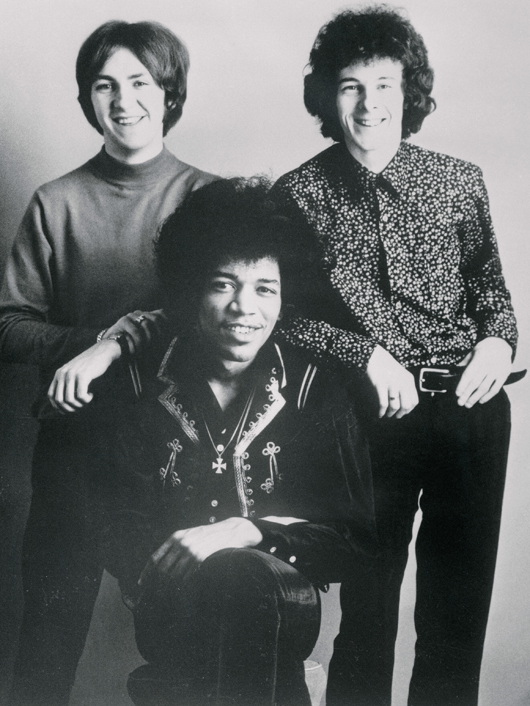

Stone Free was the first song Hendrix wrote when he arrived in England in 1966, and one of his earliest recordings with the Experience. Produced by his then-manager, Chas Chandler, it appeared as the B-side to Hey Joe.

Apparently, the guitarist felt he had a better take in him, and this recording, from April and May of 1969, puts things right. Jimi’s old army buddy, bassist Billy Cox (replacing the soon-to-be jettisoned Noel Redding) finds air between Mitch Mitchell’s drum fills that never before existed. This getting-to-know-you performance is one of playful discovery.

The tempo is slower than the original and the production is stripped down (gone are the percussive overdubs), but the mood is both intimate and party-like. Hendrix’s vocals are pure, sustained elation; he’s on the verge of becoming, transcending, and he knows it.

The gritty, gnarly guitar solo is a mini star-turn, and when Hendrix lets out a excited “whoo!” in the middle there can be no doubt that he just blew his own mind.

Valleys Of Neptune

While a demo of this cut was released on the album Lifelines, we now have what might amount to the fullest band version that will ever exist, one Hendrix had worked on from September 1969 to May of 1970.

A clean-sounding rhythm guitar drives the track, which is spacious and slightly jazzy in places. Actually, it’s a deceptively complex arrangement, full of subtle zigs and zags, with Mitch Mitchell’s nimble drum rolls providing keen punctuation.

There is no guitar solo per se, and the way the song fades it sounds as if Jimi might have been anticipating something special - a vibrant dazzler he never got a chance to realise.

Still, it’s a sassy, cosmic number, and a strong hint of what might have been.

Bleeding Heart

Incomplete, smoothed-over versions of this Elmore James cover have appeared on other posthumous Hendrix releases (Jimi Hendrix: Blues, South Saturn Delta and War Heroes), but this recording from April 1969 packs a wallop. One can only hope this is how Hendrix intended it.

The guitarist had tinkered with the song before, but now, working with Billy Cox and drummer Rocky Isaac (from a Maryland based group called The Cherry People), he quickens the chugging tempo and elongates the arrangement, most of which is an orgy of fuzzed-out, wah-wah-wonderful soloing.

Hendrix’s uncanny ability to combine guitar lines that are by turns raw and refined, spontaneous and shrewdly crafted is a thing of rare beauty. On Bleeding Heart, his artistic impulses are driven by so much emotion that it‘s a wonder the song can contain them all.

Hear My Train A Comin'

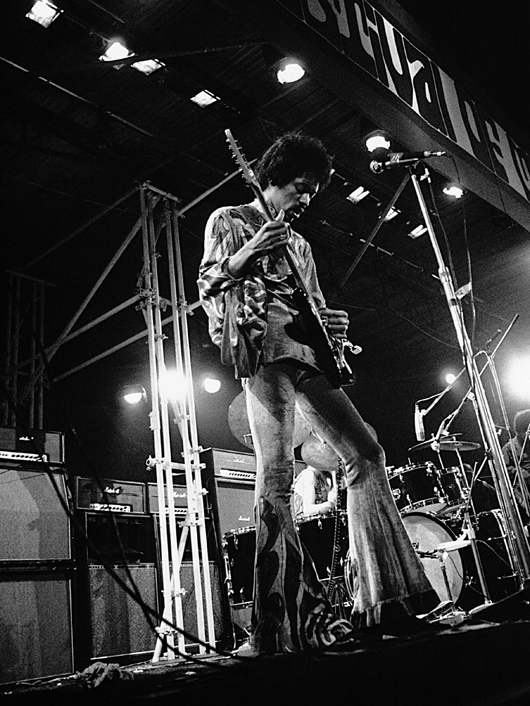

Jimi had begun formulating this original in 1967, and that year he cut an impromptu 12-string acoustic version that has been featured on several releases. But this full band rendition, recorded at the Record Plant in April of ’69 with Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, is earth-shaking electric blues, and it serves as definitive proof that, despite the rancor that may have been dividing them, the Experience could still get the job done.

In addition to pulling off some of his finest, full-throated singing, Hendrix scats impressively over a portion of the frenzied, off-the-rails guitar solo. But the real fun starts at the six-minute mark when he slows things down and lets his amp snap, crackle and pop. The man’s tireless quest for the sonic unknown is the heart and soul of this seven-minute-plus masterpiece.

Mr Bad Luck

One of Jimi’s earliest compositions, its structure at times recalls that of Purple Haze. Although Hendrix’s 1967 performance is intact, the rhythm parts were upgraded by Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding 20 years later.

Even so, the group sounds remarkably tight, organic and punchy, and Jimi’s guitar work varies from swift, crunchy chordal jabs to tubey, stinging solos. Hendrix would later develop this song into Look Over Yonder (featured on Rainbow Bridge and South Saturn Delta), but it’s fascinating to hear Mr Bad Luck in its embryonic state.

Sunshine Of Your Love

Hendrix and the other members of the Experience were huge fans of Cream, and they played this hit many times on stage. In February of 1969 at Olympic Studios, during a particularly fruitful session, they finally got around to laying it down, filling out the arrangement with percussionist Rocki Dzidzornu, who had worked with The Rollling Stones.

A Jimi Hendrix instrumental is seldom a bad thing, and in this case, it’s a a very, very good thing indeed. Each band member gets to razzle-dazzle - Mitchell’s drumming is all swinging and summersaults, while Redding digs into some grooving, distorted basslines.

As for Jimi, his playing is astonishingly elastic. At times he takes the melody far from home but he always returns to its foundation. While not besting Cream, this sure comes close. And it's one of the surprising standouts on the album.

Lover Man

Like so many of his songs, Hendrix tracked numerous versions of Lover Man, but this rendition, also cut at Olympic Studios, is more fleshed out that the recording that appeared on South Saturn Delta.

The pace is a shuffle, and the song is a good two minutes shorter, but there’s purpose behind this take. Mitch Mitchell seems to anticipate Jimi’s every tangled lick and bend - he’s got his back and he doesn’t let one second slip by.

At times, drummer and guitarist even sound as if they’re playing in unison. Jimi’s vocal is cocky, dripping with sex, and his intricate soloing is broken up by splashes of flashy rhythm-lead work.

Ships Passing Through The Night

14 April 1969 marked the last recording session by the original Jimi Hendrix Experience, and it yielded this mid-tempo, never-before-released track.

At first, Jimi’s main chordal guitar riff sounds like he’s being backed by a Hammond B3. In reality, he fed his rhythm guitar through a Leslie speaker, creating a jumping, hallucinatory effect.

Even so, Ships Passing Through The Night is perhaps this album's weakest offering. Too much of the time, it feels like Hendrix is trying to fight his way out of a box, as if he can somehow will his divine solo passages to complete the song’s fractured structure. He doesn’t get there all the way, but as always, his playing is charged with guts and determination.

Fire

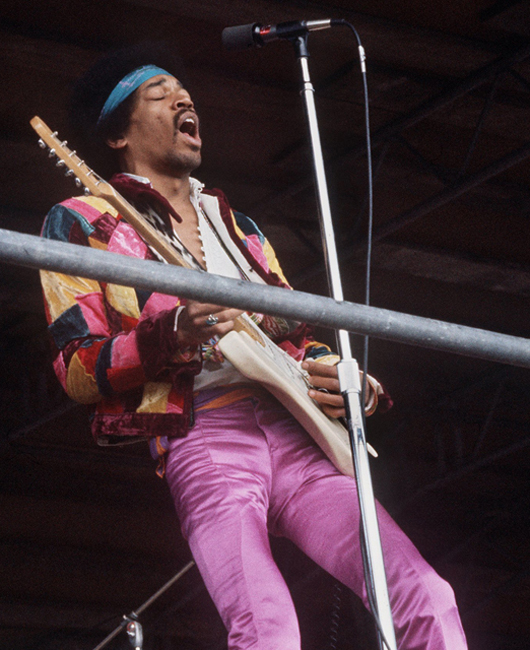

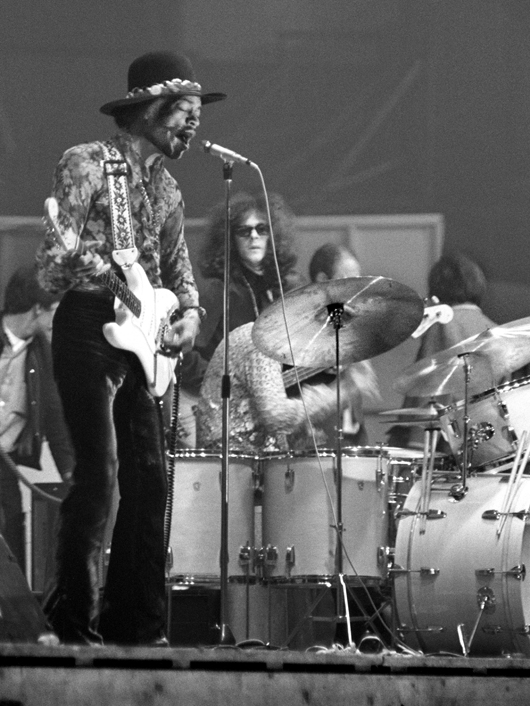

The night after recording Sunshine Of Your Love, Hendrix and the Experience returned to Olympic Studios and tracked a couple of songs from their repertoire in preparation for two concerts at London’s Royal Albert Hall, both of which were to be filmed for theatrical release.

To say the band is absolutely killin’ in this breakneck reading of Fire is like saying that cougars are fast. All three members sound as if they were shot out of the same canon, and that they manage to land on their feet together and handle their near-impossible acts of daring-do is what makes listening to this trio such a supreme pleasure.

Red House

Most listeners are familiar with the 3:44 version from the UK release of Are You Experienced? and the US album Smash Hits, but Hendrix always liked to let this song breathe on stage. Here it not only breathes, it comes at us like a slow, invigorating, sustained gust of spring air.

Not to imply that the playing is mellow. Hardly. By the time the song fades, after eight minutes of remarkably intuitive musicianship, Hendrix has unleashed so many frighteningly direct, bravura strokes and senses-altering acts of show-off skill, all you can do is say, “More, please!” So we'll say it: More, please!

Lullaby For The Summer

Also known as Ezy Ryder, Lullaby For The Summer was originally called Slow when the Experience attempted it in February of 1969. This recording from April of that year was recently uncovered.

Over a driving rhythm (and remember, Noel Redding was a week away from exiting the band), Hendrix lays down two contrasting guitar parts that bounce off each other but form a cohesive whole.

The highlight here is his skillful use of the Octavia for his lead guitar. Over a decade before the world ever heard of The Edge, Hendrix was pioneering the ways that guitarists could weave pedal effects into music. An absorbing listen, this work-in-progress.

Crying Blue Rain

Tracked at Olympia in February 1969, this song, once called In From The Storm, like Mr Bad Luck, received rhythmic updates from Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding in 1987.

Over what begins as a simmering piece of low-down blues, Hendrix doesn’t so much play the guitar as he acts with it, and he’s a authoritative communicator. Towards the three-quarter mark, the pace quickens and Jimi, using a relatively clean tone on his amp, goes wild on double-stop bends and a flurry of bass-note runs.

Musicianship aside, the song comes off as unfinished; its fade seems artificial, and after such an exhilarating ride, it's only natural to expect a rousing climax, a big bang. But an ellipsis in Jimi Hendrix's world is an exclamation point in anybody else's, and it leaves one to ponder what might still be left in the vaults. Hopefully, we won't have to wait too long to find out.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.