Jimi Hendrix producer Eddie Kramer talks People, Hell & Angels

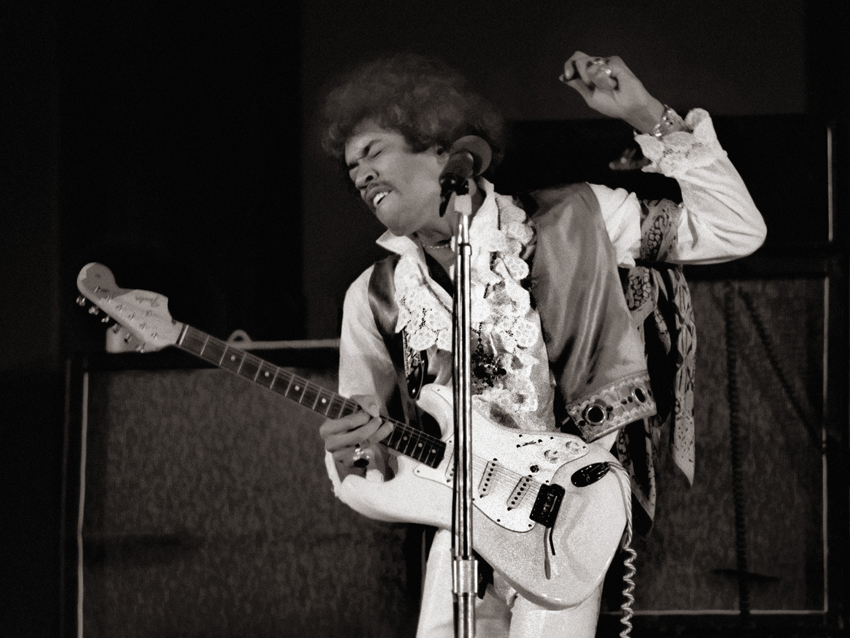

Guitarists can be hard to please, but if there’s one thing that unites us all, it’s a love – or at very least a deep appreciation – of Jimi Hendrix. So when a new release comes around, it’s kind of a big deal.

People, Hell & Angels, the latest and, according to producer Eddie Kramer, the last of the Hendrix studio-type albums to surface, throws a particularly fascinating light on the dearly departed guitar genius. Soulful, bursting with incendiary blues workouts and with flashes of horns and expanded band arrangements, this is Jimi as we’ve rarely heard him.

To celebrate the release, MusicRadar went along to the newly-reopened ‘60s hangout of legend, the Bag O’ Nails club, to see BBC 6 Music’s Shaun Keaveny interview producer and Hendrix Associate Eddie Kramer.

Click through for the full interview, pictures of the night and news of what might be next to be released from the Hendrix archive…

First impressions of Jimi

What were your first impressions of Jimi?

Ha, my first meeting with Jimi Hendrix! I was a young engineer at a studio called Olympic down in Barnes. We’d just opened to studio in January ’67, and I was upstairs in the control room. I got a phone call saying ‘hello Eddie, there’s this American chap here with all the big hair, and you do all that weird shit so why don’t you do him!’ That’s how I got the call to do Jimi Hendrix! I remember when he first walked into the studio - obviously his reputation preceded him. I didn’t do the first single or the b-side, but we started right after his initial success.

He walked into the studio, he was wearing this sort of rather grubby white raincoat, belted over. He was very shy, he sat in the corner, didn’t say too much. The next thing, I was looking out the doors of the studio, and there was Gerry Stickles, his roadie, carrying a couple of Marshall stacks. So I got a bit scared about that, but once we got going and set up, and Jimi started plugging in and getting sounds, it’s was like ‘yeah, this is amazing!’ The sounds that were emanating from the amplifier was like, wahey!

Obviously you captured such an incredible, raw guitar sound via his fingers, via the Stratocaster, via the Marshall, and people were bringing him pedals all the time. What are the challenges of getting that tone onto tape as far as an engineer’s concerned?

It was a challenge, only in the sense that when it got loud, you just had to be set. Jimi was very adept at controlling the volume, so even though the amp might have been set at ten – don’t anybody go to 11, please – he was able to control the volume from the Strat. So for instance, like on Little Wing, he would pull the volume back specifically, and not have it all cranked. Then when the solo comes, woof! You’d always be expecting the unexpected, that was the thing with Jimi. He loved messing around with pedals, Roger Mayer was always in and out of there, tweaking, getting the soldering iron out, and we were able to create some sounds that nobody else had.

He would get a sound out in the room, I’d mic in up and I’d run in the control room and start twiddling around – I think they’d call me a knob twiddler – and I’d get some EQ and some compression and some reverb, fatten it up and do my thing to it. We would go back and forth, upping the ante and trying to top each other, seeing who could top each other in terms of getting crazy sounds. It was always like that. But the one thing about Jimi I have to quickly say, his sense of humour, he had this marvellous, absolutely acerbic sense of humour. He would take the piss out of me, Mitch, Noel, and he’d take the piss out of himself too and make the session run really light.

It comes through a lot, the playfulness, in the music as well. But People, Hell And Angels, you mixed all of that, you were in the room and engineered a lot of it. What’s different about this particular compilation? To the casual observer, they might think they’ve heard some of these songs before, but they’ve never heard these performances have they?

Well, the whole idea of what we were trying to do for this album was to find as much material as was left in the vault – and we’ve been looking at this stuff a long time, we know where all the stuff is, John McDermott, myself and Janie Hendrix, the three who do all the records – so we had planned this a while back. We kept cataloguing and putting stuff aside, knowing that we were going to do, eventually, the final studio album. We found all these great performances, and we probably had about 15 or 16 songs, and we whittled it down to the 12 best.

It’s an unusual record in the sense that it’s stripped down to Jimi in the studio, just bass drums and guitar for the most part. Then there’s surprises with the horn section, his friend Lonnie Youngblood. He’s actually done a track in ’66, before he met Chas Chandler in New York, before he was discovered, he’d done a track with Lonnie Youngblood as well. So to hear him play, riffing like a jazz musician, against Lonnie Youngblood, it’s really cool, because he understood how a jazz musician thinks, and he sublimated his ego into this role of rhythm guitar. He was a session guy playing rhythm, and then when the solo comes, woof, off you go.

You’re right, that’s one of the great things about that particular track, Let Me Move You, he’s vamping, playing a lot of rhythm guitar. We hear a lot of Billy Cox and Buddy Miles as well, as it’s particularly evident in Hear My Train A Coming, it’s such a heavy rhythm. We’re used to Mitch Mitchell playing all across the kit..

OK, imagine you were Jimi Hendrix and you had done Are You Experienced, Axis, Electric Ladyland, all in a period of 18 months, and Electric Ladyland was no walk in the park, that was a double album. And so towards the middle of ’68, Jimi’s searching, he’s looking for stuff that is not quite like the Experience. He experimented with musicians and friends of his who were not in the Jimi Hendrix Experience to change the direction. He was a restless soul. And thank goodness the studios were available, he would call up the Record Plant or Hit Factory or whatever, and jam, which was fantastic – this is the result, what we have here.

And you’ve got Steven Stills on bass on Somewhere.

Can you imagine Steve Stills on bass? It’s so cool. Steve Stills was a good friend of his, and it gives it a different tone, a different vibe, and that’s what Jimi was looking for, he was trying to figure out ‘what’s my next move?’ And you’ll find by the end of 69 it peaks with Woodstock, and three or four months after that you’ve got the Band Of Gypsies, so you can see the direction he was going in.

Jimi does jazz

There was much talk at the time about Jimi collaborating with Gill Evans and going into a jazz direction..

He wanted to, yeah. It’s a funny story. He wanted to play with Miles Davies, and the word came down from Miles Davis’s office “Miles wants $50,000 or he ain’t coming down,” so that session went, see ya!

It’s also interesting to hear Jimi play with another guitar player on some of these tracks.

Larry Lee was an old friend, he played with Jimi at Woodstock. God bless Jimi he was such a sweet guy, he had a heart of gold, he was a really sensitive human being, really quiet, self-effacing, and he never let his friends down. If his friends needed a hand like Larry, he’d say ‘come and hang out’. He might not be the most amazing guitar player in the world, but he was Jimi’s mate.

A selection of questions from the floor followed:

Those very old tapes that you work with, I’ve heard they have a tendency to stick together?

Not these!

Why is that?

Because we were lucky, number one, and number two, there’s a scientific reason, I won’t bore you with the details but it has to do with whales.

The animal or the country?

It was the actual whale oil that was part of the formula for tape up until the mid ‘70s. And then of course when the whale ban happened, the tape manufacturers had to switch to something else, and that’s when we ran into trouble. But fortunately, up until 1970, we were good. We never baked one of Jimi’s tapes ever.

What's left?

Question (from Guitarist's very own Charles Shaar Murray): Eddie, one track I remember from the hideous, vandalised Alan Douglas albums of the early 70s, which I always wanted to hear a real version of, was Peace In Mississippi.

Well, it’s always possible, let’s put it this way

You can do better than that! Did Douglas screw it up that badly?

I shall never mention that name in public because if I do I’ll begin to throw up. However, I will say that we’ve restored anything that the previous administration had managed to screw up so royally, and restored it back to its original glory. So you can now hear what Jimi intended.

You mentioned that you chose from 16 unheard tracks – does that mean there’s a chance there might be another album released with tracks we haven’t heard before?

We probably even had more than 16 or 17, but the mantra is pick the best stuff, and whatever doesn’t make the album probably will not come out. Not if I have anything to do with it, because we want to keep the standards as high as possible. Now I know there are some rabid fans out there, but I work for the estate, give me a break!

Will that mean this is the last album then?

No, no, no, goodness gracious me, who said that? This will be the last of the studio type albums. Guess what folks, we’ve got a bunch of stuff in the can that’s gonna blow your mind. We’ve got tons of live stuff, and fortunately not only is the live amazing performances, but most of these performances were filmed and we have the film as well. I’m working on two at the moment, but I can’t tell you anymore because I’ll have to kill everybody and myself, and that’d be a pain. These are great. Of a scale of 1 to 10, they’re at the 10 level, and filmed.

When Jimi (nearly) met Miles

If they had actually got together, what do you think Jimi and Miles Davies would have sounded like? Did they ever talk?

I do believe they did talk, and there was always this idea of this concept of Jimi and Miles getting together. The story I told you is a small portion of what was going on between the management companies, and they just couldn’t get it together, which is a shame. But showing Jimi’s proclivity for fitting in, I think it would have been phenomenal, Lord knows where it may have gone. Those two huge egos in the studio at the same time? I would have loved to have done that one! I’m sure it would have been very challenging and very exciting, it could have changed the course of music but it just was not to be, sadly.

Were you a party to any other big-name musicians coming into the studio to jam?

Not on this particular batch, obviously there's the famous Steve Winwood Jack Casady stuff. Jimi was very clever about how he did his jams. There’s a wonderful story about Voodoo Chile. There’s a famous club in New York called The Scene, at the time it was the place, and Jimi would go there and jam virtually every night. Because, you know, we’d have to studio booked for 7:30, 8, 9, 10, 11, where the hell’s Jimi? He’s round the corner jamming! But he was jamming very specifically, searching for musicians who he felt he could rely on and would be up to his level.

This one night, he was jamming at The Scene, and Steve Winwood and Jack Cassady was there. We had the studio all set up, everything was ready, and at about midnight, Jimi comes out of the Scene club, walks down 8th avenue with the guitar, the hat, the pants, the whole deal, dragging like 20 people behind him – including Winwood and Casady – they walk into the Record Plant two blocks away, they plug in, do one run through, one take, and that’s it. That’s the master. It’s live on the floor, he’s singing live, and you can hear it – you can hear the amplifier resonating throughout the whole room. But that’s how clever he was, he would plan this out. He had this big yellow legal pad that he would write down all the instructions about where, when, how, what part of the verse was gonna be where – that man was prepared.

The picture painted in the media is of a man who, towards the end, was spiralling out of control. But in the studio that obviously wasn’t the case.

Jimi was in control, it was his album, he was the boss – you had to listen.

Will we see the Royal Albert Hall released before we die?

Before we die, yes. That’s all I can say!

There was talk of him doing much bigger projects – did he ever talk to you about these plans?

He didn’t specifically, but I know that he wanted to expand his musical horizons into big orchestral things. We mentioned the stuff he wanted to do but never got to do – the closest he got in terms of horns was that experimental thing I did at the Record Plant which is actually on the purple box set, and the stuff on this record. But Jimi, I think had he lived, would probably have had his own film company, his own TV company, and been a huge powerful force in the industry. He loved technology, and I always had this feeling that he wanted to make a movie and do all the music for it. He was a composer and a genius, to me that was going to be the next thing. Had he lived, he probably would have embraced every conceivable part of the music industry.