Jerrod Niemann talks "whacked-out demos," EDM beats and country music humor

"The real weird-sounding stuff is usually what makes it from the basement to the album"

Jerrod Niemann talks "whacked-out demos," EDM beats and country music humor

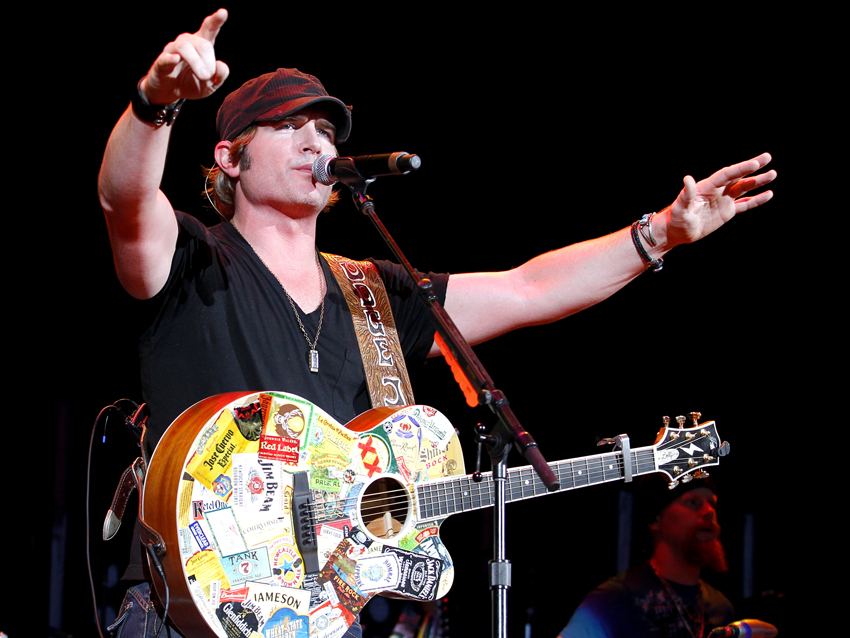

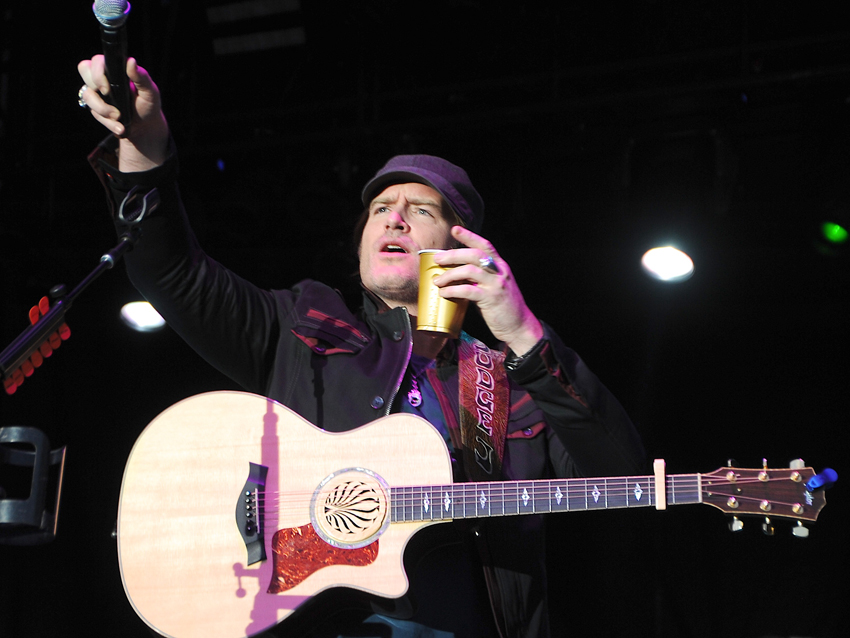

It ought to say something that Jerrod Niemann’s official fan club is called the Dehydration Nation. We’re not talking about canteen-packing wilderness survivalists here; these are folks more likely to demonstrate feats of endurance while partying hard. Small wonder, then, that the Kansas-bred country singer had his most recent number one with the amped-up, EDM-influenced tune Drink To That All Night. It was the lead single from High Noon, his third album on Arista/Sea Gayle, and it’s recently been given a second life with a remix by Latin pop-rap act Pitbull.

Amidst the daytime revelry at the CMA Music Festival the first week of June, Niemann’s current single – the equally danceable and far jokier Donkey – was being plugged all over downtown Nashville on everything from hand-held paper fans to “Ride it!” ads on the backs of pedicabs for hire. And the song is apparently already quite the attention-getter live.

Lest you get the impression that Niemann is one-dimensional, behind these two singles are a singer, songwriter and producer with broad tastes, a good ear, a vivid imagination and a healthy sense of humor, whose compositions have been cut by the likes of Garth Brooks and Blake Shelton, and who knows how to build tracks that don’t sound quite like anybody else’s.

(You can purchase Jerrod Niemann's LP High Noon at iTunes and on Amazon.)

A lot of the country party songs I’ve been hearing lately take themselves surprisingly seriously. But Donkey has a ridiculous sense of humor. What appealed to you about the combination of danceability and humor?

“I love double entendre. That song, lyrically, kind of reminded me of For Everclear or The Buckin’ Song on my first album or Real Women Drink Beer on my second. And I just wanted something for the third album that some people would think was funny, hopefully. I didn’t have any songs that I thought would make people smile like that.

“I had Donkey on my iPod for a year when we were rolling around on the bus. We’d stop in all these different cities, and it’d come on randomly in the playlist. And no matter where we were or who we were with, people would always say, ‘What is that?’

“I’ll watch movies now that I saw when I was a kid that have so many double meanings when it comes to adult stuff. So what’s funny is everybody around me that’s been reacting to Donkey is, like, my 3 year old, my 5 year old, my 8 year old love this song. …So I don’t know if that’s good or bad. And the crowd, while Drink To That All Night was at number one for two weeks, there were people yelling out Donkey during the whole show every night.”

On spoken-word songs

I saw a YouTube video where your banjo player stepped up to the mic wearing a donkey head. When you have something like that going on live, what does it do to the double entendre of a line like “riding that ass”?

“Obviously, performance is performance, but visual arts as well. You can be a little more risqué at club shows. If you’re at an all-ages show, there’s certain ways to tone it down, you know, make it more tongue-in-cheek than what it really is.

“The donkey, he’s not humping around on anybody or anything. He’s just high-fiving people. It may actually tone it down to some people. That’s the thing – music is such an interpretation. Everybody has an opinion, and the crazy thing is, every opinion is right, because it’s what you want to listen to. Hopefully we’ll get enough people that think it’s borderline okay.”

EDM-style production wasn’t one of the stylistic flavors present on your previous album, Free the Music. At what point between that and wrapping up High Noon did you decide that those kinds of beats ought to be in the mix this time?

“I started working with a different producer, Jimmie Sloas. I record at my house and then bring him the tracks; then he juices them up, enhances them, I guess. He was bass player of the year for the ACM Awards last year, and he really gets the driving force of what music can be.

“Throughout history, if you think of spoken-word songs in country music, way before hip-hop was even a genre or format, you had Johnny Cash doing One Piece At A Time and A Boy Named Sue, and you had Charlie Daniels doing Devil Went Down To Georgia and Uneasy Rider, and they were all classics that were around before rap even existed. And they were that tempo, you know, just cookin’. You look through time at Orange Blossom Special, Working Man Blues – I mean, they’re cookin’, uptempo songs. People want something to get their feet going, and their weekend going.”

Time-tested music

How much influence has hip-hop had on your delivery, as opposed to the earlier rhythmic country recitations you were talking about, more recent country acts like Big & Rich and even Beck’s wryly rapped ‘90s hit Loser?

“You’re exactly right. All the songs that I named and that you named – even Beck. That’s a great song. I’m glad that came to mind.

“I would be a fool to say, and I would be lying to say, that hip-hop really influenced my music, because I know how hard people work in every type of music, and I’m sure it would be an insult to them to even put myself in the realm of what they do. They’d probably laugh if they heard some of those songs. So to me, it’s much more influenced by our country music heroes and our founding fathers. At the time when those songs came out, and I mean The Devil Went Down To Georgia and A Boy Named Sue and even When You’re Hot You’re Hot, some of those songs that Jerry Reed sings, they were meant to make people laugh. They were funny back then.

“Anytime you’re different, people are gonna have a problem with it. But if you can hang around and fight the fight and get over that hump, people begin to trust your musical influences and your sound. It just takes hangin’ in there – enough people to finally go, ‘Oh, I get it.’”

You seem to really identify with the thread of forward-looking creativity throughout country music, which isn’t necessarily the first quality the rest of the world associates with country. What’s made you look at things that way, and what difference has it made to your music?

“Garth Brooks – I heard him one time say that time is good to music. If you hear a song that’s 30 years old, it begins to start sounding special because it’s kinda time-stamped in that day, and the way the economy was, and the technology. You think about that when you record music, that over time, time will be good to the tunes.

“That being said, the songs that really stick around, that you’ll hear played at the Tin Roof by a cover band at 10 or 11 at night is Dixieland Delight, Mountain Music – Alabama songs – because they had such brilliant pop melodies. They had every country instrument at the time and great country harmonies, so as time went on, those pop melodies stood the test of time, and they still do. That’s what people react to, the melody.

“So I just try to listen to stuff that I think, as crazy as it sounds, will stand the test of time. Because you go through eras and phases, and your music’s gonna be included with other songs during that time. I just think that you’ve gotta do your thing and hope that you’re recording music that people give a shit about.”

Making demos

At this point, it’s pretty much expected that performers will draw in flavors from outside the contemporary country realm. But you reach beyond the typical rock and pop sources. Honk Tonk Fever is a great example – it’s even got post-war jazz flavors. How is it that you seem so comfortable collecting and incorporating all of these stylistic elements? What do your record collection and iTunes library look like?

[Laughs] “A lot of traditionalists wouldn’t realize I’ve immersed myself in traditional country music my whole life. And the thing that allows me to make these decisions easily is – I don’t feel like I’m taking chances at all, because like I said before, it’s all been done.

“There’s other times that people have brought horns in, but one of the big impacts was with Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys, when he mixed country music and swing. We all know Johnny Cash has used horns, Hank Jr., even Garth and George Jones. Everybody’s used horns. And I just thought, ‘This is an important part of our history that people don’t realize.’

“I really don’t feel like I’m doing anything that different, because I know that it’s already been done throughout the history of country music, and that’s why you have Johnny Cash and Bob Wills and Elvis Presley all in the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. The people that really get bent out of shape – and I love it, because it means they care – about new music, if they really knew their history, then they’d understand that all this is repeating itself.”

You’ve described the recording you do at home as making “whacked-out demos.” What pieces of the puzzle do you put in place in your studio before bringing collaborators into the process?

“Well, I will write a song there, and I’ll figure out the tempo, and I’ll put a little percussion track together, just to have a template. I’ll sing to that, me and my acoustic. Then I’ll replace the acoustic and replace the vocal; then I’ll add a bass part; I’ll put a couple guitar parts and a couple piano parts or something, then mix it down, add some harmonies. Then I’ll take them to Jimmie [Sloas]. I don’t attempt to record them at studio quality. Sometimes we luck out and get like this real crazy sound that we can’t do again. So the real weird-sounding stuff is usually what makes it from the basement to the album.

“I do think that a piece of what sounds unique has to be some of that, just because we can’t re-create it ourselves. So maybe you just luck out and get these little textures sometimes, and it’s a lot of fun. Because then, by the time the song’s done, I know pretty much every note on every instrument, what’s being played, although the listeners will never be able to hear all that stuff mixed together.”

Audience expectations

It sounds like it’s not necessarily a matter of bringing in session guys to lay down basic tracks, then doing a few overdubs. There’s a lot more layering going on than that.

“Oh yeah, because once I take it to Jimmie Sloas, we’ll go to, like, [drummer] Chris McHugh’s house, get those guys in there all at once and let them hear the stuff that I played and just try to enhance it. Then after we do all that, Jimmy takes it to his house, and then he kinda does the same thing I did. Before you know it, we both really kinda have our stamp on it.

“What really makes me feel good as an artist working on a project together is there’s no ego involved where I think, ‘Ooh, we’ve gotta use this guitar part I made’ – I don’t care about that, because I want it to be the best. And he has no ego in saying, ‘No, we need to use that guitar part, because it’s cool.’ We just want it to be the best music together. And if you are gonna bring in different tones and sounds, you’ve gotta know your stuff, and you’ve gotta make sure the lyrics are there, because you are asking people to take a chance on something different.

“I’m not calling myself the gateway drug to country music, but there’s gotta be some artists out there that are reaching out and bringing people in. The last thing you wanna do is upset the people that already are supporting country music. You wanna do something for the real country fans, clearly, because they’re the ones that allowed all of us to be doing this. But also someone [might] hear Donkey and be like, ‘That’s crazy. I don’t like country music, but I like this song.’”

I know you used CLASP (Closed Loop Signal Processor) on Free The Music – the idea being to get the best of both analog and digital worlds. I’m not sure if you used it again on High Noon. How would the average ear recognize the impact of that on what you do?

“It wouldn’t be really consciously. It’d be subconsciously, just because it’s more of a fat analog sound. It’s the actual true record quality, back in the day. So basically, what we’re doing is we’re capturing the analog sound and instantly converting it to digital. You do get the best of both worlds.

“The thing is, when you record, you use a little compression, and then when you’re mixing it, compression, mastering, more compression. And then the radio stations compress it too. By the time you hear a song, there’s no life in it. It’s just a flat sound. What we do is we try to reduce the compression. We probably use a third or half as much as everybody else. So that way it still has dynamics. Like I said, it may or not matter. It’s just that we consciously do it because the records that we love, that we grew up on are all done a certain way. You want it to have that kind of quality.”

You’ve said you see it as your job to give people music they can party to. When and how did you get the sense that that’s what your audience wants from you?

“The truth is, what someone wants from you and what you have to offer sometimes aren’t the same things. My first gigs were playing acoustic shows in bars. Like 18 [years old], on stage, always in bars… You kind of just become a human jukebox, and when you do that for a decade, then all the sudden, because it’s all bars you’ve been playing, you kinda only know how to talk to drunk people. [Laughs]

"Also, I was raised in a household that had a lot of fun, and everybody laughed a lot. I’ve also been to a bunch of boring shows before. I’m not saying mine isn’t boring, but we attempt to make it a show for everybody that wants to be involved out there and have a good time. And really, it’s the entertainment industry. People are wanting to get something off their mind, whether they know it or not. It would be bizarre to me, and ironic, if people that were stressed came out to see you to get something off their mind, and all you do is sing sad, stressful songs all night.”

Today's country music fans

Sometimes it can be cathartic to hear someone sing a song that reflects the emotional burden you’ve been carrying.

“Yeah, a lot of times you hear those songs a couple times and you get the point. But if it’s a party song, like Friends In Low Places – when you’re out at night at Lonnie’s karaoke, you’re probably gonna hear Friends In Low Places.”

There’s a skit on your 2010 album called “A Concerned Fan” that portrays a female fan saying you ought to do more songs of interest to women listeners (i.e. non-drinking songs). You immediately follow that with a song whose hook is “What’s so wrong about one more drinking song?” How aware have you been overall of tensions between different audience segments wanting to hear different kinds of country songs? What role does that play in your decision making?

“I listen to songs and make an album as a country music fan myself. And that’s the thing – a country music fan can’t be defined anymore, you know, with one definition. I just try to look at it as the kind of country fan I am. I do try to think of others too, but I’ve got to stick with what I know, or else I’ll be playing a guessing game. You definitely don’t want to be someone that you’re not… When I make an album, when I get done with it, I listen to it all the way through – try, attempt to – as, like, a first-time listener, and I go from there.”

You were wearing a black cowboy hat on the cover of the first album you self-released, which is a very different look than the caps you wear now. Then there’s your song Old School, New Again. Did you ever picture yourself going down a more trad path stylistically, doing more of a hat act thing?

“Maybe. I don’t even really know, to tell you the truth. I worked on a couple ranches in Kansas growing up. You just sort of felt like that’s the way you’re supposed to look. I realized in Nashville, ‘Man, I’m not working on a ranch anymore. I’m playing music and sitting around in my living room with friends. This is how I’m dressed. So why don’t I just wear what I’m comfortable in?’

“Old School, New Again, it’s not saying ‘Everything needs to sound like Lefty Frizzell,’ who I even name check. It just means, ‘People who were old school were original. Why can’t everybody realize that everybody’s different and… people step forward and have their own voices?’ There’s nothing wrong with that. Traveling around to all those bars for all those years, it becomes who you are. You’re a mix of all your influences, but you still can be yourself.”