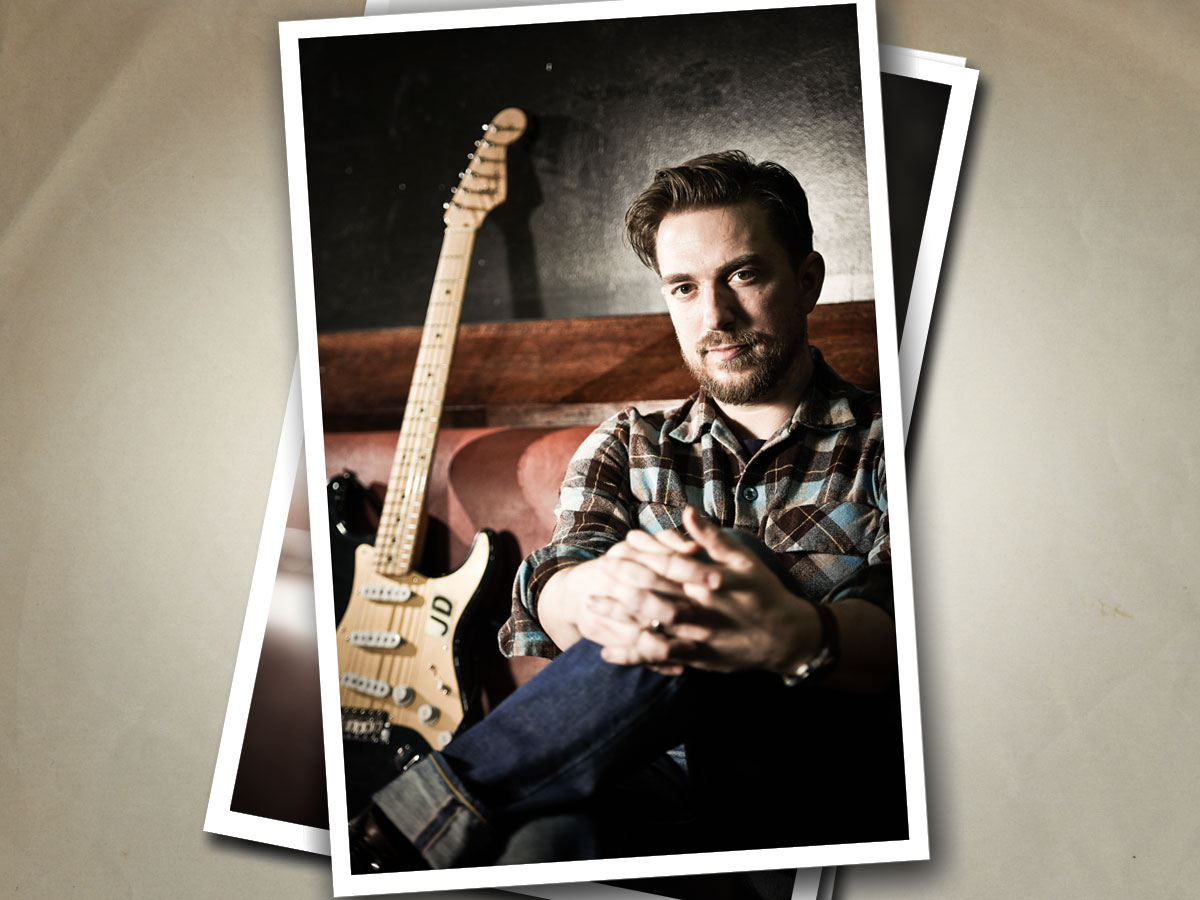

JD McPherson talks Strats, trips and Let The Good Times Roll

The R&B rocker on recording with Mark Neill

Bad medicine

Eschewing the slavish-yet-stylish retro worship of his first album, Signs And Signifiers, JD McPherson's second record, Let The Good Times Roll, loosens the tie with a mad melding of rhythm 'n' blues, Black Keys and bad medicine

"I don't tend to take a lot of medication. It's not a thing - I just don't," says Oklahoma's R&B rocker JD McPherson. "But then one night I was in pretty bad shape, so I found some cold medicine and I just took it - no big deal."

"Some jazz guys were on heroin, The Beatles were smoking grass and I'm writing stuff on over-the-counter cold medicine!"

Or so he thought. "It turns out that it was a couple of years expired and I just went on this horrible, horrible trip. Time slowed down; I could hear my heart beat, like ‘clunk... clunk'; I had cold sweats; I had this hyper-focus and I felt like I wasn't blinking."

Lest you wonder where this is going, JD is sat with Guitarist pre-gig in Band On The Wall, Manchester, recalling the inception of his second album's title track, Let The Good Times Roll.

"I was watching this episode of Frasier where they're doing Shakespeare," he chuckles. "And I had this whole alternate storyline to Romeo And Juliet, where Romeo's dead and he's expecting to see Juliet's ghost. So I wrote that song in a cold medicine stupor about that. Isn't that square? Some jazz guys were on heroin, The Beatles were smoking grass and I'm writing stuff on over-the-counter cold medicine!"

Give me a sign

The story is neatly representative of the new record's direction. While JD's first album, 2012's Signs And Signifiers, saw the Broken Arrow, Oklahoma man slavishly fashion a vintage-correct 50s-style rhythm 'n' blues collection, Let The Good Times Roll is about taking that clean-cut base and getting just a little weirder with it.

"It was like picking and choosing the weirdest stuff that happened pre-1964"

"It was just loving all of these different sounds but wanting to write better songs and experiment a little more, which is what I think it's all about," he says. "I wanted to take rock 'n' roll to art school a little bit and see what happens."

Retro freaks need not, err, freak, however: it's still a lush, analogue record packed full of honeyed Fender tones, stunning vintage outboard gear and bold, unobscured songwriting - and, in that sense, it's truer to the spirit of rock 'n' roll.

"It can be argued that it's still 100 per cent this idea of vintage recording," explains JD.

"But I pulled a lot of influence from Allen Toussaint's production with Irma Thomas, some of Owen Bradley's productions with Roy Orbison, plus a lot of country music influences. Maybe not in the singing or the songs, but in some of the sounds - the weird fuzz guitar sounds that were on early 60s country. It was like picking and choosing the weirdest stuff that happened pre-1964."

Second Time's A Charm?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the more experimental nature of the writing and recording, attempts to recreate the atmosphere of Signs And Signifiers' straightforward sessions did not go smoothly.

The first record was produced by Hi-Style Records honcho Jimmy Sutton in his Chicago studio, an experience that led to Sutton playing bass in the band full-time, but this time around it wasn't working.

"Mark Neill has one of, if not the greatest vintage analogue studios in the country"

"It completely crashed and burned," recalls JD. "It became apparent that we needed another treatment. That's when we started looking at outside studios and producers and we found the right one in Valdosta, Georgia with Mr Mark Neill."

Mark Neill is the engineer/producer behind The Black Keys' 2010 breakthrough Brothers, the man who designed both London's Toe Rag Studios and Dan Auerbach's Nashville base and, before any of that, the creator of numerous garage-rock and psych hits.

"Mark Neill has one of, if not the greatest vintage analogue studios in the country," says JD, with some authority.

"He's been doing it since the 70s when it was cheap and no-one wanted that stuff any more. Capitol Records was auctioning off, like, [ jazz/ swing great] Louis Prima's conga drum, and he got it. Microphones, microphone stands, he built his own console, he's got all the Ampex [reel-to-reel] stuff, he's got two EMT plate reverbs... It's like recording with Owen Bradley."

Neill know-how

"It's not just the equipment," JD emphasises. "Studio equipment is important, of course, and you should be pragmatic, but it's really about the engineer and the knowledge of how to record and how to make sounds happen. And Mark definitely has that."

"It's always like: ‘Don't touch that, for God's sake! Don't you turn that amp knob! You wanna get shocked!?'"

A disciple of the oldest arts of recording know-how, Mark Neill is of the ‘read a f **king book' school of production. A believer in designing rooms according to the rules of the golden ratio, he quite literally knows the maths behind a mind- blowing kick drum sound. Recording with this kind of personality at Neill's Soil Of The South studio was, as JD says, an "intense" experience.

"Valdosta, Georgia is a sultry Southern town with hot, damp air," says the songwriter. "You go into Soil Of The South and it's like a municipal building from the 1950s. It's got wood panelling on the walls and old stuff everywhere, but it's very clean and orderly.

"Mark is very meticulous. A lot of his stuff is modded and he makes you feel like anything could explode at any moment. It's always like: ‘Don't touch that, for God's sake! Don't you turn that amp knob! You wanna get shocked!?'"

Under My Thumb (Piano)

We picture a scene akin to Marty McFly laying down tracks, while Doc Brown mans the desk, but JD says it was also Mark Neill's attitude that made him a good fit for Let The Good Times Roll.

"He understood that we didn't want to make reenactment records. He was into this stuff, but he's not afraid to push the envelope a bit."

"I used a Fender Blackie-style Strat and a Rickenbacker, and I fell in love with both of them"

Which is good, because this is an album that reels in everything from African thumb pianos (Bossy), to Auerbach-ian staccato riffing (Head Over Heels), and on the soulful Bridgebuilder, Brian Wilson levels of tenderness.

"That one was a lot of fun to make," says JD of Bridgebuilder. "It was probably the first one I wrote after Signs..., and Dan from The Black Keys helped me write that song, but it wasn't working until we went to Mark's... He really instilled a lot of confidence in me about my singing and songwriting, made me feel a bit more confident in what I had to offer."

That new-found confidence in the songwriting is apparent in the simple palette of instrumentation. Thumb pianos aside, JD - a lifelong Tele devotee - became totally enamoured with a Blackie-style Stratocaster owned by Neill, a fact he's still recovering from.

"I used that and a Rickenbacker, and I fell in love with both of them," explains JD. "The Rick was a really nice one. I don't know the model number [likely a 300 Series], but it was a 50s or early-60s style - one of the great big semi-acoustic ones with checkerboard binding.

"It's one of the most versatile guitars I've ever seen. I was getting Link Wray sounds out of it, Mickey Baker sounds. You can play almost everything. That guitar and the Blackie Strat through a 50s Magnatone amp is it. That's all I used! And a Gibson acoustic."

Magnificent Magnatone

Magnatone has been making something of a comeback since the brand was revived in 2013, but Neill is a longtime convert, meaning that despite JD hauling his 15-inch speaker, hand-built Fender Pro-style Texotica combo nigh-on 1,000 miles from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma to Valdosta, Georgia, it still didn't get a look in.

"If Mark likes the sound of something, he'll use it, it doesn't have to be period-correct"

"It's the only amp in Mark's studio and that's the only amp anyone's allowed to use!" says JD of the mystical Magnatone. "We brought a van full of amps down there and we didn't use any of them. Mark might let you compare them, but I tell you, I wish I had that Magnatone in my collection, because it was just magic. He just moves it, so it's either in the hall or in the room, or another part of the room, or facing one way, facing another way - and it totally changes. He knows it inside out."

One of our favourite tones on the record is the soul-shaking tremolo sound on Precious and, having conjured up images of a beaten-up AC30 ageing gracefully in a studio corner, we're now somewhat perplexed about its origins.

"That's actually one of Mark's pedals. It might have even been a Boss [TR-2], which you would never think!" reveals JD.

"If Mark likes the sound of something, he'll use it, it doesn't have to be period-correct. He had this weird little fuzz box that plugs directly into your amp and then you plug into it. The paint had worn all off of it, but it's just the size of a matchbox. It's some little thing he bought for 20 bucks in the 70s, but that's his fuzz."

The thrice is right

While the gear decisions were, er, streamlined by Mr Neill, Let The Good Times Roll was still a challenging record to make.

Despite the help of Dan Auerbach, the aforementioned Bridgebuilder had about three or four lives before it was finalised, while Let The Good Times Roll was recorded at three different studios.

"This is a terrible analogy for a man to make - but they say that with childbirth, you don't remember the pain!"

"When we first did that, everybody said, ‘That's going to be the first single' and I was like, ‘Well, that's really great, but I really wish we could get it right!'" laughs JD.

"We went into the studio with no demos. Nothing was fleshed out. Everything was up here [points to head] and we were trying to get things worked out, and sometimes it happened and sometimes it didn't... They say - and this is a terrible analogy for a man to make - but they say that with childbirth, you don't remember the pain!"

It nevertheless feels like a hit, as though Let The Good Times Roll could do for rhythm and blues what The Black Key's Brothers did for blues-rock. So, despite the accidental trips, Mark Neill's "intense" genius and the maddening re-writes - what made him realise that he'd birthed a worthy successor to Signs...?

"My wife," he concludes after a pensive moment. "When I would play her tracks back. She's the last editor for me. I put the headphones on her and played her the tracks and she looked up and was crying. That was when I was like, ‘Okay! We're good!' That was the best review I could get. I don't care what anyone else says!"

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.