Jason Aldean discusses expanding his sound on new album, Old Boots, New Dirt

"I'm constantly gonna go out and try to make each record sound different and have fun"

Jason Aldean discusses expanding his sound on new album, Old Boots, New Dirt

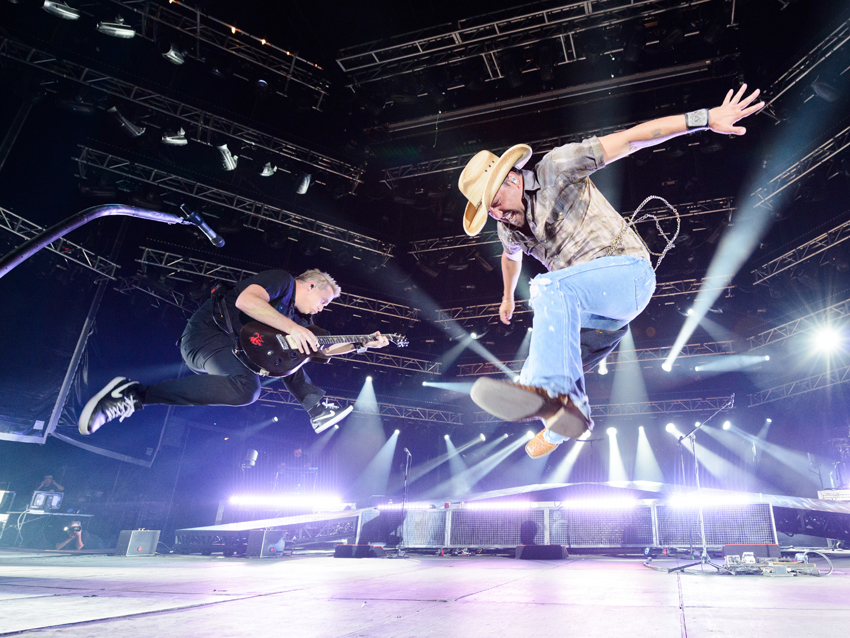

Jason Aldean just made his sixth album, Old Boots, New Dirt, with the same core trio of musicians who played on his first project, his fifth and each and every one in between. Drummer Rich Redmond, guitarist Kurt Allison and bassist Tully Kennedy are also the guys who flank him on arena and stadium stages and help put on his bruiser of a hard-rocking country show.They toughen up his music videos, too.

Aldean wanted to be the kind of country superstar who had a real, permanent, integrally involved band, which was a rare breed of country superstar indeed when the Georgia native debuted in the mid-‘aughts. That and the fact that he’s been working with the same producer, Michael Knox, all along have branded Aldean with a sound that’s remained aggressive even as it’s incorporated textures like programmed drum loops – and even as he’s dabbled in country-rapping on a few big singles, like Dirt Road Anthem.

MusicRadar asked the 37-year-old singer how and why his way of doing things has worked for him over the past decade. (Old Boots, New Dirt will be released on October 7. You can pre-order an exclusive signed copy of the album, and a digital download of the record at Jason Aldean's online store. You can also pre-order the album at iTunes.)

There’s not a very long list of country superstars who’ve ever reached the point of being able to sell out stadiums as a headliner. You may well have been the first male artist of your generation of country superstars to get there.

“I know when I was younger and going to concerts, George Strait was doing a stadium tour. Garth Brooks was doing some of that stuff. And then Kenny Chesney went on to do it a little later on. In the country music world, that was about it. So to think that you can get to a level where you start playing stadiums, that’s almost, like, an afterthought.

“You’re happy to be able to go into arenas and sell those out – small arenas, like, 8,000, 10,000 seats. You start doing amphitheaters and you sell those out for a couple nights in a row. Then you start thinking about, ‘Man, we could do two or three nights in an amphitheater, or we could do one big show in a stadium.’ And that’s when it really starts to hit ya: ‘Man, this has gotten way bigger than we ever thought possible.’”

You played your first stadium dates after you’d made Night Train. Did reaching that level change anything about the way you approached making the new album?

“I think every album we’ve ever made has been basically the same mindset. It’s all about finding great songs. Once you find the songs, everything else kind of falls into place. Whenever we finish an album, we immediately start looking for songs for the next record. We spend a couple years, at least a year, year and a half trying to find these songs. We typically have been able to stockpile great songs that way, by looking for ‘em over the course of a year or two."

The drum loop on Burnin' It Down

“The mindset of going in to record an album is, you find great songs, you go in and record ‘em and you sort of put your stamp on ‘em, make ‘em sound like you. It’s one thing to go in and do something and it not work, and then you back up and reassess everything. But for us, the things we’ve done always seem to have worked well. So there’s really no reason to change our approach.”

Do you think at all about the kind of territory you want the songs to cover and how you want the song sequence to flow?

“It’s not like I go in and go, ‘Well, this is gonna be the theme of this album.’ I don’t go in looking to have a theme for the record. It goes back to the songs. I think the songs you find sort of dictate what direction the album takes.

“You narrow it down to the 15 songs that you feel like represent you and what you do, and things that you feel like you can pull off and that really are gonna add to your show, or you think are gonna be great singles. Some of ‘em you know aren’t gonna be singles and you’re like, ‘Man, that’s just a really cool thing for the album.’ We go through hundreds and hundreds of songs to find 15. You wanna make sure you’ve got a few tempos, some ballads, some mids, kinda change it up a little bit.

“In the case of this album, Burnin It Down is just a completely different-sounding record. Then we’ll have some of the more rock stuff, the My Kinda Party stuff. Then we’ll have some of the more traditional things. It’s that formula that we’ve used for every album. Then when you get ‘em all done, you sit down and figure out how you want it to flow.

"You don’t want to pile up a bunch of slow songs in a row. You want to kinda spread it out where you’ve got a tempo and maybe a mid and a ballad or two and then another couple tempos. You want it where when people listen to the record, it doesn’t get boring. We spend a lot of time listening to the album in different sequences trying to figure out what sounds the best, what’s gonna get their attention and keep their attention for a while.”

You brought up Burnin’ It Down, which is almost an R&B jam. For you, that’s a different kind of feel for a lead single.

“Yeah, it is. It’s amazing how much putting a drum loop on a song can change the sound of it. Obviously, a lot of things in the hip-hop, R&B and pop worlds, all that stuff is very loop-driven. It’s rare that you even hear a live drum on anything. With this song, Burnin It Down, it’s so predominant. It’s not like it’s sorta hidden in the track. It’s very much in your face and letting you know that this is a drum track. And that was done intentionally – it doesn’t sound like anything else we’ve ever cut before."

Provoking a reaction

“Same thing when we put Dirt Road Anthem out. You had this group of people that loved it and thought it was the coolest thing they’d ever heard, and then you had this group of people over here that hated it and thought you were ruining country music, because it had hip-hop in it. That, to me, is exactly what I want. I want people to love it or hate it. I get just as much joy out of somebody going, ‘Man, I hate that song’ as I do with somebody saying they love it. Because at least you’re hittin’ a nerve with ‘em. At least they’re not just sittin’ there saying, ‘It’s OK.’ I think that’s the worst thing anybody can say about your song, that it’s ‘OK.’ To me, that means it’s elevator music and it didn’t do a thing for ‘em.

“You’re gonna have some guys that come out that are gonna be traditionalists, that are gonna stick to that very right-down-the-middle approach to makin’ records. And I’m just not that guy. I’ve never been that guy. I’m not gonna be that guy. I’m constantly gonna go out and try to make each record sound different and have fun when I’m in the studio and have fun with the songs that I record.”

When you arrived on the scene, it felt like the first time that not just arena rock influence, or the Eagles’ influence, but harder rock had a presence at the center of country music. What felt right about that combination to you?

“Well, I think everybody else noticed it probably more than I did. To me, I didn’t realize we were doing anything that different really. I thought it was cool. I knew that the stuff we were recording didn’t really sound like anything else out there, that it was a little edgier. But I mean, I didn’t realize it was that big of a difference. Because that was the way I’d always done it.

“I’d always been a fan of rock and southern rock and blues and R&B and whatever. So when I was learning to play musically, basically in the clubs as a kid, I was playing all the stuff I liked. And it could’ve been an Allman Brothers song. It could’ve been an Alabama song. It could’ve been a Guns N’ Roses song, Waylon [Jennings] or whatever. Whatever I felt like playing at the time, that’s what we played. It just seemed like a lot of the stuff we did, it was almost like a rock band with a country singer. And that’s kinda what it ended up being.

“Came to Nashville and hooked up with a group of guys that are my band now that really sort took that sound to the next level. Those guys were just better players. Really, between what I brought to the table and what they brought, it was magic pretty much. I mean, we got in the studio and it came out the way it did. We felt like we were onto something really cool.”

On his band

You used the phrase “a rock band with a country singer.” That’s definitely the image your music videos have portrayed. From the beginning, they’ve featured your band playing with you.

“Those guys are just as big a part of everything as anybody. They’re the ones that sort of helped me create the sound. Without those guys, it would sound a little different. They play on all the records. I also wasn’t gonna be the guy that makes my band all wear the same outfit, these little bolo ties or whatever you call them. I just told those guys from day one, ‘Be yourself. I don’t care what you wear on stage. All I care about is that you go out and help me put on a show for people. That’s all I care about.’

"Because those guys going out and helping me entertain people sort of takes some of the weight off of me a little bit. We’re like anybody else – there’s nights where I go out and maybe I’m sick; I’ve got a cold or something. So it helps to have those guys come out and help you carry the show.

“They had been doing this music thing as long as I had. So they had a good idea. And I think that’s really why it worked. We all kind of knew the way we wanted to be sort of portrayed in videos and all. And really, we’re a band. I’m the guy that’s out front. It’s my name on the records and all that stuff. But I mean, ultimately, when we get on stage, we’re a band. Those guys have been huge in helping create that sound and the live shows and all that stuff.”

If you count the years you were doing demos and showcases with those guys, it’s around 15 years you’ve been playing together.

“I met those guys in ’98, ’99. We started playing shows together in ’99, I think. Played a lot of showcases. That’s sort of where we started to dial it in a little bit. The more you play in a band with somebody, the more you start to figure out what they’re gonna do before they do it.

“When I got my record deal, it was kind of a no-brainer: ‘Let’s go. This is what we’ve been waitin’ on, so let’s get to work.’ Those guys were ready to go. I didn’t have to go out and throw a band together with guys that I didn’t really know, and get in somewhere and rehearse for a couple months. When we first got started, there was me and three other guys, [bassist] Tully [Kennedy], [guitarist] Kurt [Allison] and [drummer] Rich [Redmond].

"We were all on a bus and we were a four-piece band out there playing. We since have added a couple pieces to it. But early on it was just the four of us, and we went out with a guitar, bass drums and acoustic guitar, and just went out there and gave it everything we had and created this sound like we had this huge band – and we really didn’t. But the one thing we did have was – I don’t know – chemistry, I guess.”

On "traditional country"

Your longtime producer, Michael Knox, came from a song publishing background. Do you feel like he’s also been an important piece of the puzzle for you?

“Oh, absolutely. Michael, he’s the guy that I can count on. The thing with Michael and me is, we’ve worked together for so long. He knows the kind of songs that I’m into, the types of things that are close. There will be songs that he hears that he thinks we should cut.

“Dirt Road Anthem – I mean, that was Michael’s brainchild. He knew that it was different; he knew that it could be a hit at country radio, and he knew that there was an audience for that out there. That’s the thing with Michael – he’s not scared to take chances, and he’s very opinionated on what he likes and what he doesn’t like. He’s a guy that I trust when it comes to songs. We’re not always on the same page, but 95 percent of the time we are. And it’s cool to have somebody like that, that you feel is kind of your partner in the business.”

Dirt Road Anthem was the first song of its kind to go number one on the country charts.

“Dirt Road was a career song for me. It’s been the most downloaded song of my career. I think it sorta opened the doors for a lot of other guys to be able to come out with songs – guys like Florida Georgia Line – to come out and sorta do stuff in that same vein.”

People heard a different side of you when you recorded Going Where The Lonely Go for the Merle Haggard tribute album last year. It was an up-close, intimate vocal performance. What was that like for you?

“When people listen to the albums I make, the thing they don’t realize is, my dad was a huge traditional country music fan. I grew up listening to it, singing it. That’s how I learned to play guitar, by playing those songs. Silver Wings by Merle Haggard was one of the first songs I ever played on stage. Just because I don’t record traditional country music doesn’t mean that I don’t love it and that I don’t enjoy playing it occasionally and listening to it. I mean, I still listen to it, a lot.

“Doing something like the Haggard tribute record was a cool thing for me, because it allowed me to go and record music in a way that I typically wouldn’t on my albums. I liked it because I knew a lot of people were going to be like, ‘Wow. This is a completely different sound. This is traditional country.’

“Well, yeah. I love that stuff. I’ve never said I didn’t love it, but it’s just not what I wanna go out every night and play on stage for two hours. We just got a chance to go out on tour with George Strait, and I got a chance to get up on stage with him and do a couple of his songs with him. And that’s awesome. I love doing that stuff.”

On the band Alabama

You also got to pay tribute to one of your big influences on that Alabama tribute album.

“Anybody who’s followed my career knows Alabama was my favorite band of all time. That’s my biggest influence, probably ever. One of the things I loved about ‘em was the fact that they could take country music and sort of blend it with southern rock and create this sound that was unlike anything else that was on the radio at the time. The effects they’ll use on Jeff [Cook]’s guitar. And they’ll use flange on the vocals. I don’t even know how they were getting some of the sounds they were. The drums sounds they were getting were so weird and electronic sounding. It was just different. I think that’s what was cool about it.

“I got a chance to go and record on that tribute record. That was one of the highlights of my career – we recorded Tennessee River. I don’t think that song was much of a stretch from what we do as much as the Haggard stuff was. But to go and play songs that I grew up playing – I never in a million years dreamed that I’d be in a studio recording with Alabama.”

Did the fact that Alabama were a band make you want to have a band?

“I think so. I like the idea of it. I know the Mountain Music album had the four of them on the front of it, and they’re sitting there with their arms around each other. A very ‘70s picture, but it’s really cool. I always thought the image of a band was really cool.

“Honestly, had I had the opportunity to be a part of a band and be a singer for a band, or even be a guitar player in a band, I think that [would’ve been] cool. For the same reason as me growing up loving sports; it’s that team effort thing and the camaraderie with the guys. Some of the best times I’ve ever had were just traveling around on the bus, just me and my band.”