James Taylor talks new album Before This World

The songwriting great on his playing and writing process

Introduction

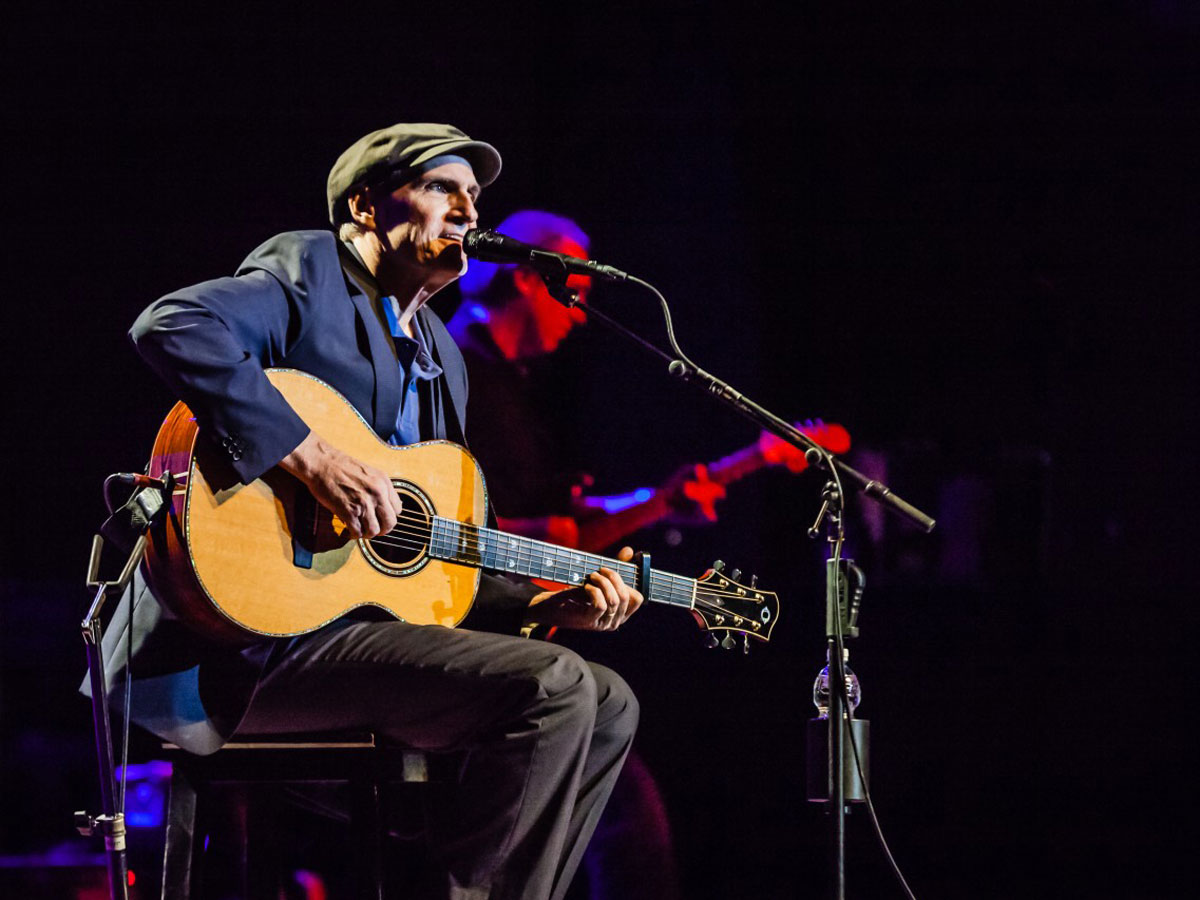

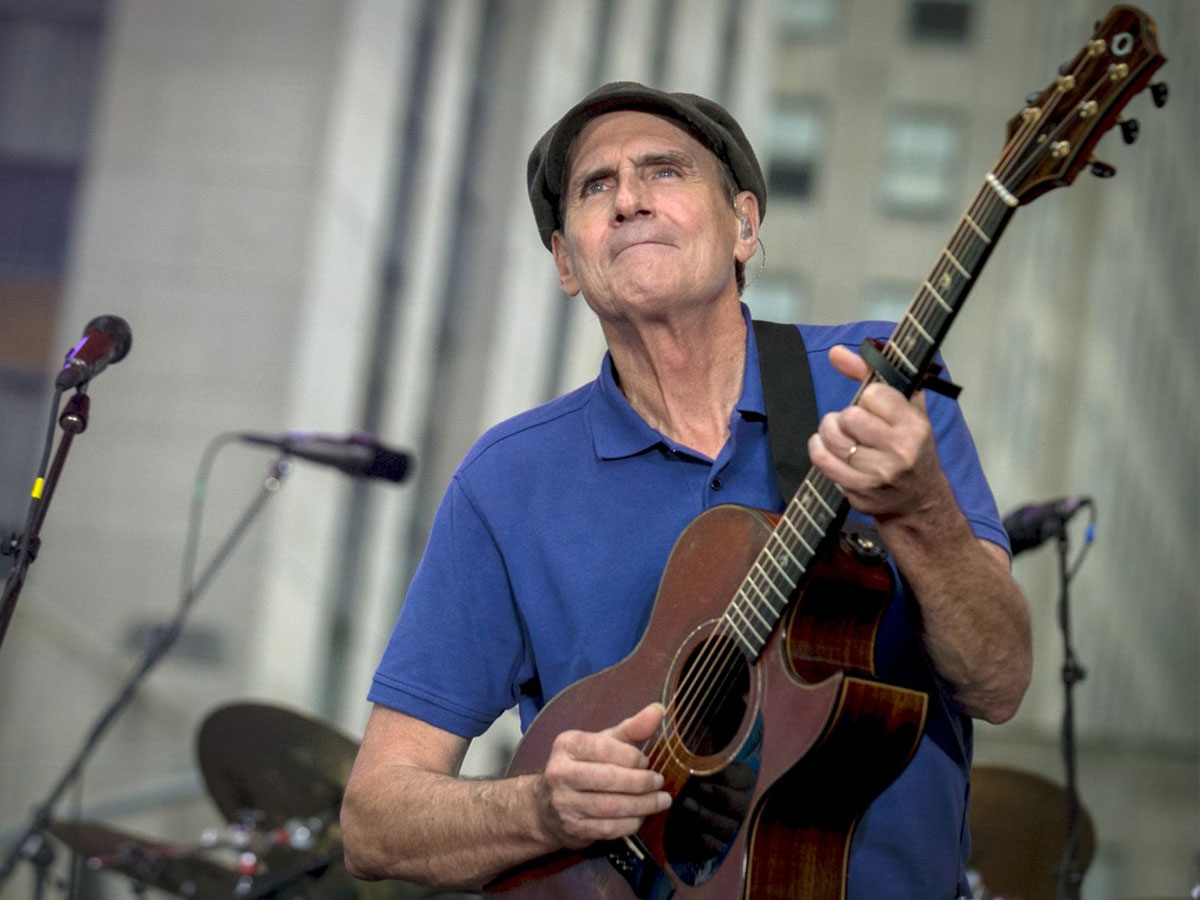

With Before This World - his first album of original compositions since 2002’s acclaimed October Road - James Taylor is back on form: vocally, as a great fingerstyle guitarist and as composer of deeply personal songs.

James talked exclusively to Guitarist about the new record, his stunning band, and what it’s like for an erstwhile acoustic minstrel working in the digital age...

"While Dylan and Donovan played straight major and minor chords, Taylor’s style brimmed with major and minor 7ths"

It’s rare for an artist to define an entire genre, but when it comes to guitarist-singer-songwriters one man stands apart. This quiet, self-effacing minstrel from Boston, Massachusetts came to prominence when the 60s were all but done.

The joyous pop of the decade had given way to self-indulgent blues-rock, deafening stacks of amps and 15-minute guitar solos. Even Dylan had gone electric. The time, it seemed, was ripe for a subtler, more introspective style.

While Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Judy Collins, Carole King and a host of others were plying their trade in the coffee shops of New York and Los Angeles, it was Joni Mitchell and the tall, quietly spoken intellectual James Taylor that defined their respective genders’ role in this new singer-songwriter movement.

A famously troubled individual, Taylor’s life and music would be informed by bouts of depression, psychiatric institutions and chronic drug abuse. Yet his lyrics and music, while deeply personal and often cryptic, connected with a generation let down by hippy promises and hedonistic excess.

His music was sophisticated, too: while Dylan and Donovan played straight major and minor chords, Taylor’s fingerpicked guitar style brimmed with major and minor 7ths, slash chords and intricate trills and figures that stamped their mark on every song. It sent a million wannabes scurrying for that old flat-top under the bed.

Man Of The World

With over 100 million album sales to his credit - his Greatest Hits sold over 12 million copies in the US alone - Taylor has been selling out concerts for over 40 years now.

"I’m a bit nostalgic for analogue, but I doubt I’ll ever go back"

Attracting the world’s finest musicians like moths to a street lamp, his band is always populated by the finest players of their era. His 1997 Grammy Award-winning Hourglass marked a new high both writing and production for the artist; its follow-up, 2002’s October Road, was similarly well received, but Taylor has not released any original work until now.

Continuing the tradition of fine song construction, state-of-the-art production and fabulous playing, Before This World tackles personal and world issues with equal care. But how does James Taylor go about creating an album in these digital days?

“I’m a bit nostalgic for analogue, but I doubt I’ll ever go back,” Taylor begins. “It’s all going to be digitised eventually. Recording digital gives you much more editorial capacity to manipulate things afterwards, and it’s just too good from the mixing point of view.

“The point about analogue is that the microphones, the speakers, the amplifiers, and all the things that manipulated the signal evolved together. And then when they made this divide, where there was the analogue side going to digital, it took digital a long time to integrate. But with faster sampling rates and higher bit rates, it’s getting so much better.”

Born In A Barn

Taylor now records in a studio in his barn at home on Martha’s Vineyard, an island off the Massachusetts coast near Boston.

“Hourglass was the first album we made on available home studio machinery,” he elaborates. “It was totally revolutionary. About $20,000 bought you an entire studio, so from that point on I’ve always tracked in my own space.

"My kind of recording is the consensus approach of teaching the players the tune and seeing what happens"

“That sense of the meter running in the old studios was a drag, so it’s nice to be able to relax into it and feel as though you have all the time you need. The barn is one I used for storage and rehearsal, but it turned out sounding so good that we’ve used it more and more.”

Is a James Taylor album a layer-upon-layer affair, or do he and his band play largely live?

“I tend to want to track with as many of the instruments playing as possible,” he reveals. “The other way is to write everything out and ask everybody to ‘play the ink’, or put down a drum machine, guitar and voice and then selectively layer things on. But my kind of recording is the consensus approach of teaching the players the tune and seeing what happens when they bring their own take to it.

“They get to use their musical choices and it turns out to be far more interesting. But it takes musicians who are willing to listen to each other and maybe let somebody else have the reins.”

Taylor teaches the songs to the band a number of ways. “Sometimes I make a demo, and the guitar suggests the expanded arrangement,” he continues.

“Other times I’ll cut demos with just Steve Gadd and Jimmy Johnson, to make a good first iteration of a song. They take notes and write their parts out in whatever form they can most readily read and remember it.

"We have Jimmy Johnson and Steve Gadd playing bass and drums, Larry Goldings on keyboards, and Mike Landau playing guitars"

“It’s been a long time since I wrote out chord charts but I used to chart out the songs, make copies and pass them out to the band and they would play it and we’d discuss it.”

On bigger shows Taylor takes out as many as 13 musicians, including four backing vocalists, brass and percussion. But the nucleus of the production is a quartet of A-list virtuosi.

“It’s amazing,” says Taylor, as if in disbelief at his own pulling power. “We have Jimmy Johnson and Steve Gadd playing bass and drums, Larry Goldings on keyboards, and Mike Landau playing guitars of all stripes. That’s the basic group, and I have my four singers, plus percussion and horns.

“I did the Covers albums [Covers in 2008 and Other Covers the following year] because I wanted to record those 13 people live. Before This World has those four main players and myself. We cut a track a day for 10 days and that’s 90 per cent of what you hear on the record.”

Refining The Process

Even once they’re learned, Taylor likes to refine the songs further before they’re committed to ‘tape’.

“Well, you’re recording the song for all time, but this is the first time everyone’s played it. If you could tour a batch of songs for 20 or 30 gigs I’m sure that things would settle. In the studio you’re trying to do that first time, so we tend to do a lot of takes - 20 takes or so for each song.”

"I buy a notebook for every song I write, open it up so there’s a blank page to my left and to my right"

As Taylor is so involved and knowledgeable about digital recording, the writing process surely involves laptops, iPads or even mobile phones?

“No, no iPads,” Taylor states emphatically. “I buy a notebook for every song I write, open it up so there’s a blank page to my left and to my right, put down what I’ve got now and then start making changes on the left-hand side.

“I use lined paper, and on the line opposite I’ll put an alternative, then flip the page over and do it again. Eventually, you can see the song develop; how the form of it has changed and how I’ve edited the lyric together.

“Things will have a working title,” Taylor continues. “Far Afghanistan was called ‘Irish Heroic’ - I was thinking more about Ralph Vaughan Williams than anything else there. The working title of Montana was ‘Three-Four Folky’, and Angels Of Fenway was called ‘G Nation’, for some reason. So I’m aware of what the character of the song is going to be.”

Star Power

A staggering roster of celebrity singers has joined Taylor on his records over the years, from various Beatles, Joni Mitchell and Carole King, through to his ex-wife Carly Simon, Stevie Wonder, Bonnie Raitt, Simon, Garfunkel, JD Souther, Crosby, Nash, issue 392 cover star Mark Knopfler and many others.

Sting contributes vocal harmony on the new album’s title track. Taylor becomes uncharacteristically animated when talking about singers and singing - harmony vocals in particular.

"That’s a great part of my thing, arranging vocal choral music. I spend a lot of time at it"

“I worked with Graham Nash and David Crosby on two albums - In The Pocket and Gorilla. They sang on Mexico - and that sounds like Crosby, Stills & Nash with those three voices, even though Stephen Stills’ voice has such a strong character.

“The surprising thing is that people in a stack of vocals will glue it together in a way that you wouldn’t expect. Carole King is a great person to have in a stack of vocals, as is [renowned backing vocalist] David Lasley. I’ve worked with a lot of great singers - George Jones, McCartney and Harrison - and that’s a great part of my thing, arranging vocal choral music. I spend a lot of time at it.

“These days I tend to sing all the parts. I use a pitch shifter to drop the key down so I can sing the high parts, then shift it back up so it’s in key, then we’ll re-record it [using the backing singers].

“Actually, on Angels Of Fenway I kept a lot of my Melodyne vocals to build that harmony stack. It’s a great tool to be able to sing all the parts, even beyond your own range.”

Fingerpickin' Good

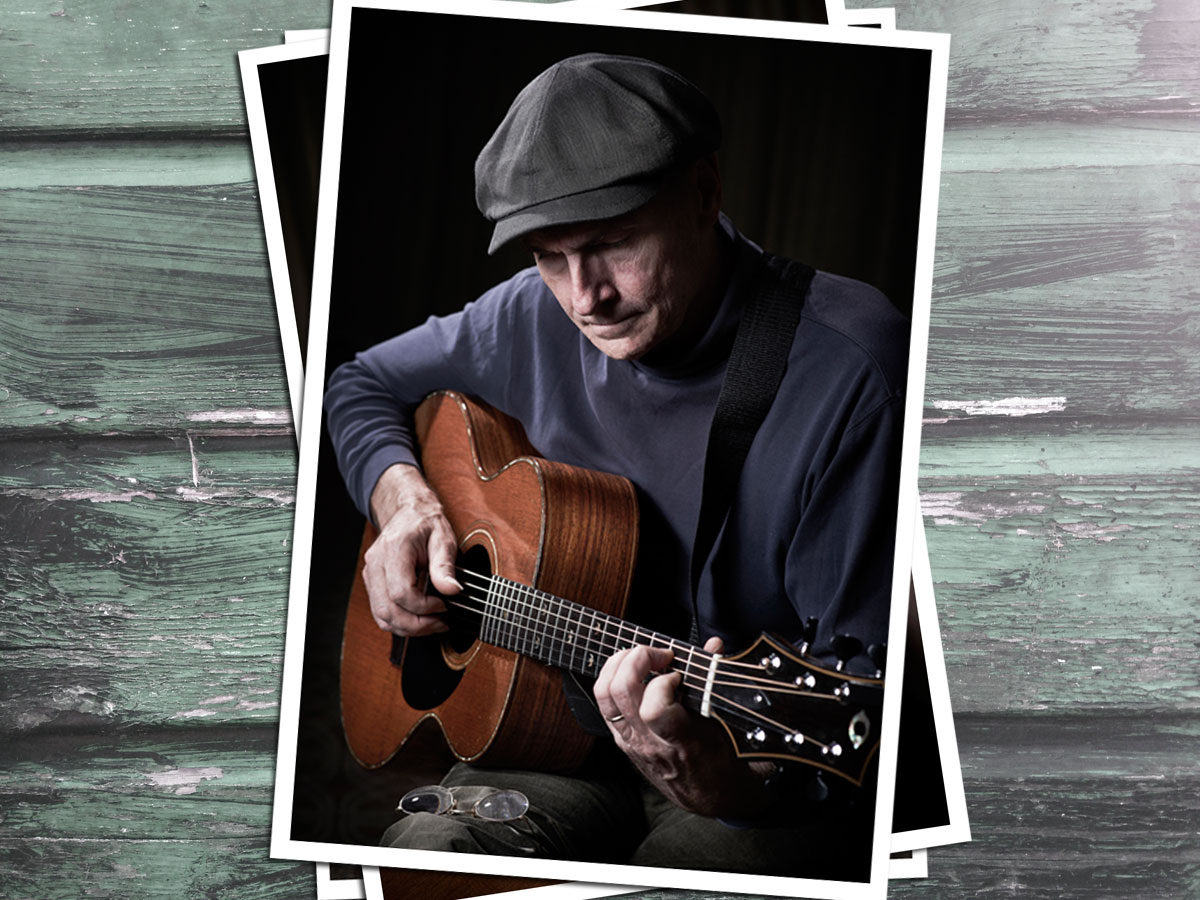

We know Taylor to be a fine acoustic fingerpicker. But he also plays electric. Could he surprise everyone by knocking out a stinging solo on a track like Steamroller Blues?

"Thumb and strum is what I tend to do. I very seldom actually strum - I’m always using my thumb in that ‘flailing’ type of style"

“No, probably not. Sure I can play a solo, but it’s just a slightly punched-up version of what I’d play anyway. I’m not a virtuoso guitar player; I’m an accompanist, not a soloer. I play a bassline with my thumb and play internal lines with my index and middle fingers. I’m basically bracketing the arrangement on the guitar and using it to accompany myself.”

But what about strumming - would he ever grab a pick and bash out a tune?

“Again, no. Thumb and strum is what I tend to do. I very seldom actually strum - I’m always using my thumb in that ‘flailing’ type of style.”

Apart from the occasional drop D, Taylor is not known for open tunings, either...

“I have written a few songs in G tuning - which to me is really an A tuning but down a whole step,” he reveals. “Love Has Brought Me Around [from Mud Slide Slim And The Blue Horizon] and a couple more. So I tend to stay with regular tuning, but I do like the drop D.

“Occasionally, I write on piano - I can’t play it, but I can write on it. Then I show it to a keyboard player and he works out how to play it properly. You And I Again on this album was written that way.”

Cutting The Chords

Since his very early days, Taylor’s chords and progressions have been marked by a harmonic sophistication uncommon in ‘folk’ styles.

"From a very early time I was simply constructing what I wanted to hear, chord-wise"

“You find that if you play a V chord over a I, that is a I in the bass and a V chord on top - say, a D chord over a G bass - you get a major 9. I love that sound. I also like playing a II chord over a I bass - say, an A chord over a G. It’s a sound that really wants to resolve and you really hear the thing drop into place when it does.

“When I learned to play the guitar, I learned some of my chords from other people, but some of them I’d just construct - like I knew I needed this note in the bass and I needed a chord above it.

“Also, I don’t play a D or A chord like anybody else; I play the 3rd in those chord shapes with my index finger, so you can really pull off and hammer on strong. So, from a very early time I was simply constructing what I wanted to hear, chord-wise.

“It wasn’t unusual for me to play an F chord and take the ring finger and put it over on the G bass note to create a IV over V [or 11th]. The other thing is that my playing is very ‘straight 8ths’, in that it has almost no swing at all. That ‘straight-up-ness’ means I have to really hammer on strong - as on Fire And Rain.”

Take It To Church

Taylor’s list of influences ranges from Cuban and Brazilian to... English Church music?

“I’m a folk player, which means I’m sort of drifting and responding to a lot of different sources,” he points out. “A Cuban ‘tres’ player - that’s a six-string guitar with three pairs of double strings - called Nadar Arsenio Rodriguez was a huge influence on me.

"I’d say at the base of it all is the Church of England standard hymnal. That was the first thing I played"

“Then there was Jobim; that sound of the bossa nova guitar was also a huge influence. Then Kootch [Taylor’s guitarist friend Danny Kortchmar] taught me blues and gave me a really strong sense of that stuff, exposing me to it in a major way. So these things come along.

“But I’d say at the base of it all is the Church of England standard hymnal - Jerusalem, A Mighty Fortress Is Our God, Once To Every Man And Nation. That very standard Western sound was the first thing I played - Christmas carols, too. I was also exposed to a huge amount of show music - Broadway music - when I was a kid; my parents listened to a lot of that and our record collection was very rounded.

“Angels Of Fenway reminds me of that loping ‘trot’ type meter of Surrey With The Fringe On Top [from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!]. It has a simple melody line and the first iteration is in the key of G; it then has the same melody in the relative minor [E]. That’s a trick I use a lot - the same melody line with different chords underneath.

“The opening song, Today Today Today, uses the same melody line when it falls into the bridge but over very different chords. If you had to play that melody over and over again it would drive you nuts, but it’s a vocal vehicle.

“Far Afghanistan reminded me of a Vaughan Williams Fantasia On Greensleeves or something. How it ended up being a song about a soldier preparing to go to war is because it’s something I just can’t stop thinking about, what it must be like to be in that situation. So, influences come from far and wide.”

World Class

While chatting to one of the great songwriters it seemed obvious to ask Taylor what, in his view, makes a great song, and which tracks on Before This World stand out to him. “A song either hits you or it doesn’t,” he suggests.

"The thing I like to think about it is that this is the thing I’m meant to do. To write, record and perform music"

“A song can be really carefully prepared and balanced; the lyric can be offset by a contrast in the harmonics beneath it. It can be like Cole Porter’s You’re The Top, that’s just a delight to listen to, or it can break all the rules and still work. But you can’t decide ‘I’ll like this or I won’t’.

“That’s why music is empirically true; that’s why it gives us the release that it does. It’s of the real world; it’s a human language but it follows the laws of physics; and what is harmonic to us, while somewhat culturally determined, in the end I think is more about mathematics.

“On this album I’d say my best songs are You And I Again, Far Afghanistan and Snowtime. But Angels Of Fenway, Stretch Of The Highway and Before This World surprised me also.

“The thing I like to think about it is that this is the thing I’m meant to do. To write, record and perform music. And I just want as many people to hear it as possible. Not to force it down anyone’s ear but to make it available. For some reason I still find that compelling.”

Full Circle

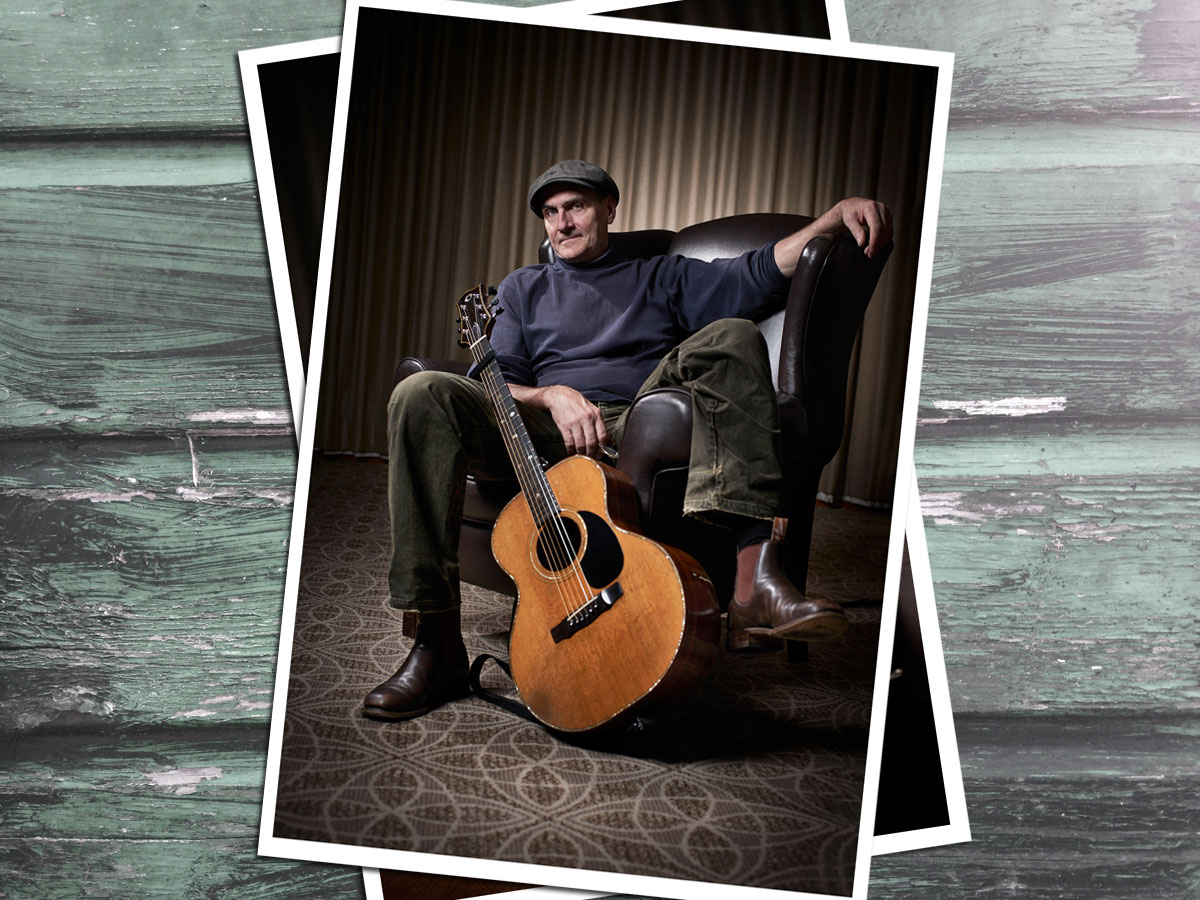

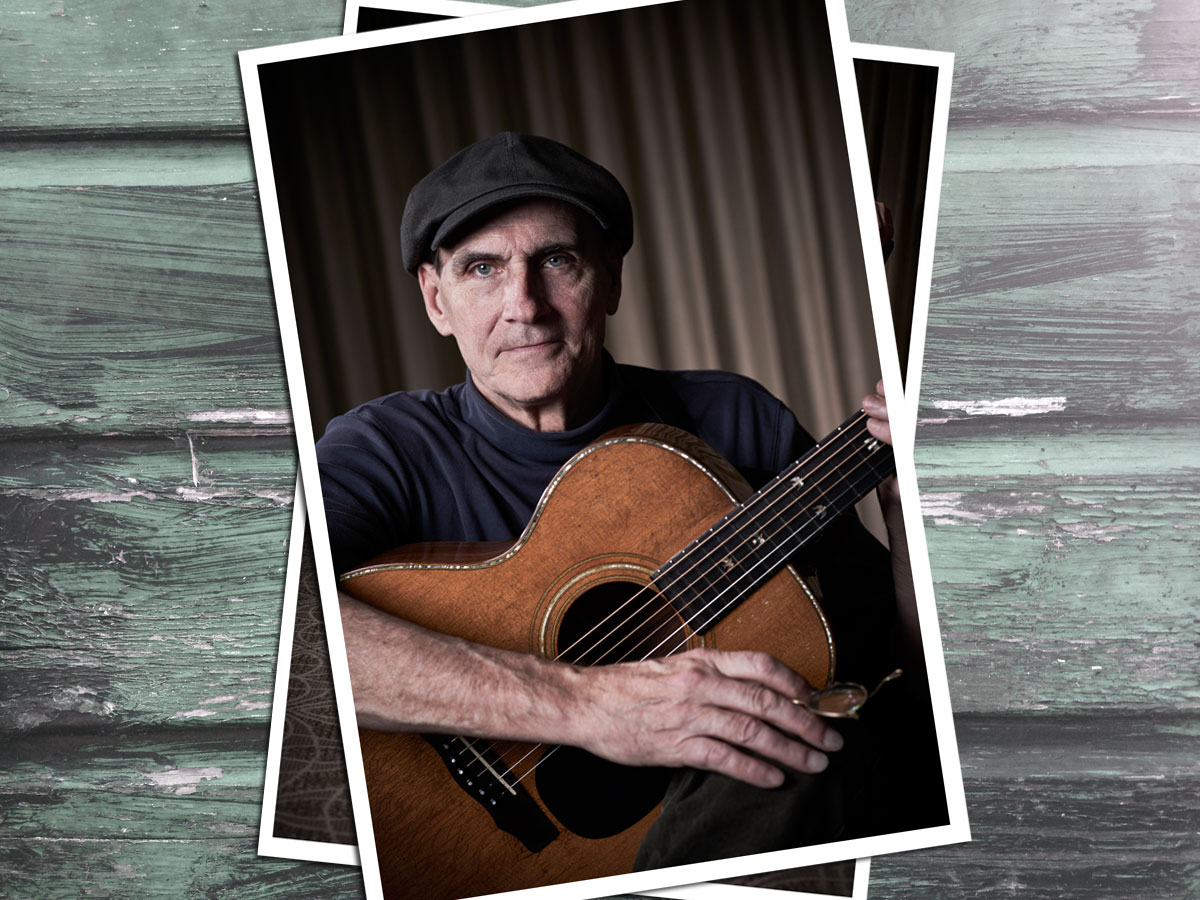

Over his long career, James Taylor has used a variety of guitars to shape his sound. When he first came on the scene in the late 1960s, his guitar of choice was a sweet sounding but light-toned Gibson J-50.

"James Olson had gotten this guitar into my room, and when I picked it up and played it I knew I had a great new guitar"

He’s remained faithful to just three main acoustic guitar brands since then, but has been playing instruments built by luthier James Olson of Circle Pines, Minnesota since 1989.

“I used my Gibson J-50 for the first 12 years or so, then John McLaughlin introduced me to a guitar builder called Mark Whitebook [the jazz-fusion guitarist worked with Taylor on his 1972 album, One Man Dog, on which he played a stunning acoustic solo on the track Someone].

“Mark built two guitars, one for me and another for my then wife [Carly Simon]. Hers was actually a little better than mine so mostly I played that one. But when we got divorced, understandably she wanted it back.”

Then in 1989, after a gig in Minneapolis, Taylor arrived back at his hotel only to find a surprise on the bed - a guitar made for him by James Olson.

“He had gotten this guitar into my room, and when I picked it up and played it I knew I had a great new guitar. It’s slightly wider at the nut than normal so it fits my hand better.

“It has a cedar top and rosewood back and sides. It rings and has a very bright sound but it’s balanced, which means you can get a good bass note out of it. The action is low. I like it just on the clean side of buzzy.”

James Taylor’s new album, Before This World, is available now on Concord Records. Visit www.jamestaylor.com for more information.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues