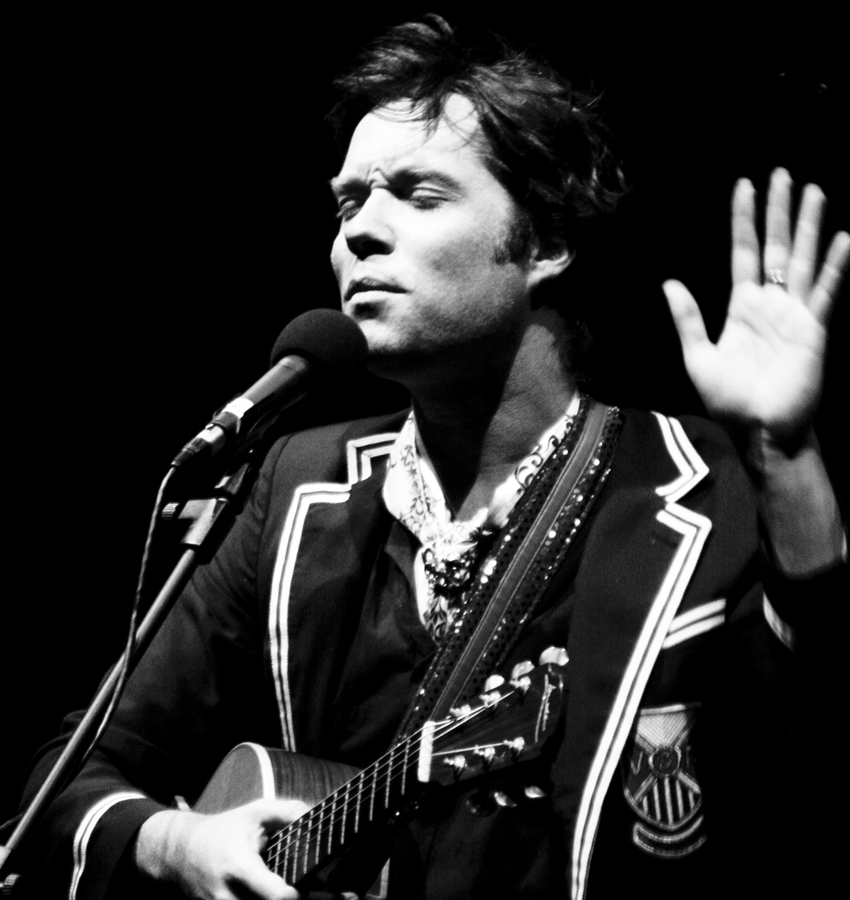

Rufus Wainwright lightens up - but is no lightweight - on his winning new album, Out Of The Game. © Barry J. Holmes

Singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright is the first to admit that he's made eclecticism work for him. During the course of his still-brief career, he's tackled indie-pop, cabaret, opera and even a Judy Garland tribute. On his new album, Out Of The Game, he frames his uncanny melodies and luxurious voice against inside musical milieus that recall, in varying degrees, the hazy, laid-back spirit of early '70s pop-rock.

For the most part, it's a light, breezy listen, but that doesn't mean it was an easy place for Wainwright to get to. Years of personal turmoil, including the 2010 death of his mother, folk singer Kate McGarrigle, were explored on albums such as All Days Are Night: Songs For Lulu.

On the new set, Wainwright decided to lighten his load. "It was time to unwind," he says. "I was ready to make the leap to more of a pop thing. I had the chops to do it and to still say things that are significant. And I had to make sure I had the right producer to do it all with."

He found him in Mark Ronson, whose hip, cagey, retro-soul stylings worked wonders for Amy Winehouse, among others. Ronson set Wainwright up with a loose collective of musician friends (the Dap-Kings, Nels Cline, Sean Lennon, Andrew Wyatt) over the course of two months in New York, and the result is an album that mixes shades of Muscle Shoals, blue-eyed soul, doo-wop and even disco into one smooth, elegant ride.

But all is not whimsical on Out Of The Game: The riveting, solemn set-closer Candles, penned as a memorial to his late mother, is as emotionally devastating as anything John Lennon laid down on on John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.

We sat down with Wainwright recently to discuss how he came to work with Mark Ronson and the ways in which the two channeled the music of their childhoods on Out Of The Game.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

As an instrumentalist, who were your influences? Where do you draw inspiration?

"Well, I do not consider myself a guitar player. My father is a guitar player - I'm not. [Wainwright's father is Grammy-winning musician Loudon Wainwright III.] I mean, I can play chords, and I have a certain feel. I can get around the instrument fine. I'm a pianist… at times. In that respect, the artist who gave me the most inspiration and direction, especially as a singer - and I absolutely consider myself a singer, 100 percent - is Nina Simone. She's my ultimate pianist-singer-type person."

Both you and Mark Ronson cite Harry Nilsson as a reference for this album. What do you get from Harry's music?

"That's hard to say... It's true, I love Harry, and I love Randy Newman and Brian Wilson - that whole era. I wouldn't say that I strayed from or ignored that genre, but for a long time I kind of stayed away from it. Maybe it was too close to home. I wanted to carve out my own niche and sound, so I always went for things that I couldn't achieve, like being an opera singer or anything to do with classical music.

"I'm only now coming back into the fold with a lot of those artists, which I think is a good thing - I don't sound like I'm imitating them necessarily. But I didn't go back and listen to their albums before we went into the studio. Mark may have, but I didn't. I like live music. I like going to the opera." [laughs]

Mark Ronson works the DJ booth in New York City, 2009. © WWD/Condé Nast/Corbis

You and Mark knew each other socially, but how did you decide to work together?

"Our publicist, Barbara Charone, who is also a dear friend to both of us - she's our UK publicist - she has an affinity for great music and great looks [laughs] - two things that Mark and I both own. She put forth the idea that we might work together, and we picked up the deck of cards and ran with them. It turned out to be a very smart move.

"There was an immediate affinity between both of us. But you know, I've chased hotshot producers in the past, and in most cases, it's very hard to land them, especially when they've had big successes in the recent past. Mark immediately wanted to work with me. He kept returning my calls, and kept getting in touch with me, saying, 'OK, when is this going to happen?' So it was nice to feel a real desire on his end, which isn't always the case with big producers because they're often so busy."

Sonically, what were you looking for that Mark was able to deliver?

"The general quality of the sound he got is superb in terms of how the instruments are recorded, and the fact that most of the technology he utilizes is analog initially - that's how we recorded it, and then we moved it to some cute computer stuff later on. But the base of it is very organic. That's great - it gives a real depth and warmth to the experience.

"What's equally important and accomplished is where Mark places my voice in the track. He really managed to get me in the pocket and make it an even experience throughout the whole album. So you hear me, but you don't get sick of me, and that's been a problem for some people in the past, this kind of constant 'Rufus clamor.' [laughs] Which I love! But Mark managed to 'subtle-ize' my voice, if that's even a word."

On any record, there comes that time when a producer has to tell an artist that something isn't great, or a song can better. How did Mark push you to reach higher?

"He was very honest about his feelings towards things, but it was never final in terms of the situation. I would present something, and he would say, 'OK, I'm not nuts about that, but why don't you keep trying?' It wasn't this arduous search to please him.

"Finally, I would come up with something he liked. But he didn't put pressure on me or anyone - except maybe the engineer. [laughs] Musically, it was a blast. It was a quick process, which gives it a certain lightness and brightness."

Did Mark play on it at all?

"He played some guitar or bass here or there, but not a ton of instruments. When we started the process, before the real sessions, he made demos of all the songs, playing all the instruments - drums, guitars, bass. We cut them all again with the Dap-Kings, and he stepped out of the way at that point.

"His demos were great, and one day they will be released. The whole album exists in a whole other format with Mark doing everything. It'll avail itself at some point."

Mark is quoted as saying he heard a kind of Laurel Canyon-meets-Young Americans vibe for the album. Did the two of you talk in those terms?

"We mentioned those things, yeah. As I said before, Mark is the real audiophile and knows about that stuff. I have kind of a vague idea. But really, I'm more of an opera buff. [laughs] I think it's partially our lack of common knowledge that made this more of an interesting experience.

"For instance, I wrote all the string parts, and I'm the one who took care of the backup harmonies. Those are places where I could bring my slant to stacking and chord structures to the table, juxtaposed with his intimate knowledge of recording through the ages."

So Mark made full demos, but what about you? How did you present the songs to him?

"I would just use a solo guitar or a piano, very bare bones."

The song Out Of The Game has some great guitar playing. The solo is reminiscent of George Harrison.

"Yeah, well, that's Homer [Steinweiss] on that. A lot of the band members are from the Dap-Kings. Usually, they're relegated to a more '60s R&B sound, but for this record they had to open up and were given a chance to explore their chops. I think they loved every minute of it, being on this vacation from what they're known for."

The drumming on Rashida is very expressive. When you write, do you have a sense of how you want the drums to be played?

"That song is a prime example of Mark stepping in and making it his own. Originally, Rashida was more of a slow, mournful, somewhat tongue in cheek ballad that I intended on recording with just me at the piano - it would be something of a break from the band. Mark heard this ferocious claptrap and just flew with it. [laughs] That song I owe 100 percent to him and his ideas."

"My father is a guitar player," says Wainwright. "I'm not." © Simone Cecchetti/Corbis

There's a real early '70s vibe on the song Barbara. It's soulful - you're telling a story almost.

"Yeah, you know, the '70s thing is interesting. Unlike, say, Amy Winehouse, who was fantastic and a legend - I wish she was a living legend - but she inhabited this late '50s-early '60s sound that was very effective and worked very well with her voice. But she wasn't from that time period; she was slightly imitating that era.

"I don't think that's the same as me and Mark referencing the '70s. I mean, we were born in that decade, and I have memories of that era. That vibe and that feel surrounded me as a child. So we both own it a little more, but the way we went about it on this record wasn't deliberate. It was like we were digging into our primordial past by going back to that era. It made sense."

Candles holds a powerful lyrical meaning for you, obviously. Musically, however, when you presented it to Mark, did you know what you wanted?

"I would say that, whereas Rashida is Mark's song 100 percent, Candles is my song 100 percent. Very graciously and intelligently, Mark gave me free reign with the song. We tried a couple of things with drums at one point, but it became obvious that I had to do it my way. I dictated the full structure and production of the piece, and Mark facilitated it for me.

"It has my family, it has bagpipes, it has funeral drums… I knew where to go with it. Mark was there the whole time listening, appreciating and supporting me - mostly emotionally. It wasn't an easy song to do."

What surprised you the most about working with Mark?

"One of the most consistent surprises was how funny he is. He's hilarious, and so charming. Throughout the entire process, there was this steady level of fun that he maintained. I don't know - I totally fell in love with him."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track