INTERVIEW: Metal production guru Colin Richardson

We meet one of metal's most successful record producers during his latest project

Colin Richardson

Carl Bown

He doesn't have long hair, he doesn't crush beer cans against his forehead and as far as we know, Colin Richardson doesn't even have a tattoo.

Yet this softly spoken man is responsible for some of the hardest-hitting guitar music to ever batter an eardrum, having engineered, mixed and produced his way into the metal cognoscenti - with Carcass, Napalm Death, Machine Head and Slipknot among his extensive credits.

"I think with metal, you're always looking for clarity... But I found that with tape, you were always struggling to get that clarity."

We met up with him at co-producer Carl Bown's studio in the Derbyshire hills, while tracking guitars on the new album for UK metallers Rise To Remain.

Richardson began his studio career straight from school, captivated by the sounds of Sabbath and Zeppelin. "I started as a tea boy, really," he recalls as we begin chatting and filling in some history. "My mum came along with me, and she tried to get me an extra £2 a week!"

A few years later, following a stint at a residential studio in Driffield, Yorkshire, he was contacted by Earache Records founder Digby Pearson to ask if he'd like to become a producer.

"I'd actually been producing without realising," he recounts, "but I was still amazed! Did you say you were going to pay me as well?!"

How do you react to the constant changes in recording technology over the years?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I think I've always chased it. I first came across ProTools in around 1999 and I loved it straight away. We were struggling with some drum parts and the engineer at the studio showed us how to copy things and move things around."

A lot of people were still arguing about how great tape sounded at that time…

"I think with metal, you're always looking for clarity - it can be between 200 and 240bpm! I found that with tape, you were always struggling to get the clarity.

"Like, if an album was being done over a period of three months, your drum sound would tend to degrade. I think albums almost take longer to make now than they used to, because there are so many options with ProTools.

"If you have 20 options, it's worth exploring them, because option 19 could be the incredible idea. But with tape, you either erased it or kept it. In theory you'd think it'd be quicker these days!"

Do you feel exasperated when the whole thing then gets squashed into an mp3 and listened to on a mobile phone?

"It's the same for everybody. You play the tone game and try to get it better than everybody else. So hopefully when everybody's gone down to the mp3, yours should still sound the best. I don't mind that - it's just technology.

"You just need to get it to where you love it and it sounds great - and I like to think I've got high standards. If I'm brutally honest, there are maybe only two mixes I've ever done that I'm even 98 per cent happy with."

And they are?

"I think that Chimaira's self-titled record [2005] and maybe the first Bullet For My Valentine one [The Poison, 2005] still stand up pretty well. But even then you hear it and you go, 'Well, I still think the toms could sound better… Could the bass have been louder?'"

During the recording process as producer, are you more diplomat or dictator?

"I'll answer the question slightly differently. It's 60 per cent psychologist, 40 per cent technical ability. Mixing is completely different, of course, but if the band is saying, 'That's bad and that's bad…' or if I'm doing that, then we shouldn't be working together."

And when it doesn't go well with a take?

"You just try something different. Even turning the lights down - something old-school such as that, or turning the monitors up. Or somebody cracks a joke. But if you make the same mistake 15 times or something, you need to look at what you're playing.

"I'm sure that people play their best stuff in their bedroom - a studio isn't the most relaxing place, so it's all about getting on and having a laugh."

Where do you start for a great guitar sound for hard rock and metal?

"It starts with the guitar. For this record [Rise To Remain - Bridges Will Burn] we had two PRSs with EMG 81s. We had five guitars in total with EMGs and they all sounded completely different.

"The guys have about 10 personal guitars, but we didn't use any of them. Oh, and there's a Telecaster with a Rio Grande pickup that we used as well. That thing into a Marshall just has its own space.

"Then we'll go into a Tube Screamer just to tie in the bottom-end - which is something everybody seems to do - into a [Peavey] 6505 head and a Boogie [Rectifier 4 x 12] cab. There's a [noise] gate in there as well to stop the hissing."

How loud are the amps when you record?

"Loud, but not ear-splitting. It's working and you're going to feel it, but it's not insane you can still go in the room. If you don't have it at a decent volume, you won't get the weight and there's always that nice mid- range when the cab is being pushed a bit.

"So if it excites you, but your ears can still take it, that's the right volume. We're just below three on the master on the 6505, sometimes up to four."

What about cabinets - where do you like to mic them?

"The cab has been the same all the way through - the Boogie with Vintage 30s. This is actually Andy Sneap's cab [producer of Cradle Of Filth, Machine Head and Megadeth] and it's been used on so many records. It's a slant one.

"We had a bunch of straight ones as well and maybe it's psychological, but they didn't sound as good - not as much low-end or as much smoothness in the distortion.

"We spend a long time on the mic position. If a cab gets a lot of use, there might be one hot speaker, so we put the mic straight in the middle - which isn't the best place - then we'll record 20 seconds of a riff, and listen to each speaker with the same riff and choose the best speaker. Only then do we position the mics where they sound good.

"We use a Shure SM57 and a Sennheiser 421 - I think that's what [legendary US rock producer] Bob Rock used back in the day!"

Are the two mics recorded to separate tracks, or summed to one?

"Separate tracks, just to keep the options open. In the tape days, you couldn't have done that - it'd be two tracks, then quad-track the guitars - that's eight tracks for one guitar, which is obviously too many on a 24-track machine. But now we can, so we keep it on separate tracks because we're not sure what might want to lead off volume wise, the 57 or the 421.

"It might be that the verse sounds better with the 57, but the chorus with the 421, because it has a bit more mid, for example."

And room mics?

"We don't use them. The further away you go, the less in-your-face it sounds. As I said, we're quad-tracking all the guitars, so once you get four rhythms playing the same thing, there's an ambience, a natural flam that makes it thick sounding.

"I've tried room mics, but I just get into awful trouble with them."

You mentioned quad-tracking - how are you approaching that?

"Well, we have two tracks of the [Peavey] 6505 and two tracks of a Bogner [Uberschall]. Sometimes all four parts are the same, then sometimes it'll go into harmony - it depends on the part.

"Until you get into the studio, you can't hear all the nuances and that's where your experience comes in. At least with ProTools it's easy to pan it around, or take it out, so you keep your options open."

What about EQ with guitar tones?

"We messed about for a day finding the right mic positions and I was determined not to use any EQ - we use the tone controls on the amp.

"I will EQ heavily in the mix if I think it needs it, but I'd like to think I've got it as true as possible. But if you're EQ'ing heavily when you record, and again when you mix, you're getting into some weird phase stuff that even I don't understand.

"I'd rather change the guitar to change the tone, but I have no problem EQ'ing like a maniac in the mix if I'm fixing something that's been recorded badly.

Do you get into re-amping?

"I will if I'm mixing something and I don't think the guitar sound is working. It's almost like playing God. But then as Carl says, 'Don't live on the edge - take a DI [feed] just in case,' so we do. Metal is pretty methodical and clinical, it needs to be clear. I wonder if an indie band would do DIs and re-amp?

"All of us, including bands and labels, have a sound based on [metal music] since Pantera; based on how metal 'should' sound. I've been as guilty as anyone of playing the game, but the songs are different and the players are different, that's what makes it different."

How about the perennial recording nightmare for guitars: tuning?

"We must have spent 20 days tuning on this job. Y'know, not full days, but we've had a whole load of tuning problems. Basically, we're trying to get a lot of high- gain distortion onto a lot of six-string chords with a lot of clarity.

[Guitarist Ben Tovey then goes on to explain that certain chords, particularly major sevenths, never seem to sound properly in tune under heavy distortion.]

"So if we couldn't get it to sit, we split the chord up into the three parts where we record the lowest two strings, then the mid strings, then the high strings - Def Leppard style!"

Guitar heroes: we're seeing a new breed of super-schooled player coming through at the moment - from your position as a producer, do you think guitar players are getting better?

"Yes. They've had to - drummers got better, so guitar players have had to as well. But I'd like to think that the art of songwriting shouldn't be about how fast you can widdle.

"Hopefully there are still some good songs. And with solos, even with shred, you tend to remember the slower sections - it's the four-note repeated loop that sticks in your head.

"Ben here is in the top few players in metal in the UK - he really is. The album needs to come out and people can hear it. We want to bring the guitar hero back and it's not a joke - it's been gone too long and it should be cool again!

"You'd have to go back to the '70s and '80s for British guitar heroes. Has there been anybody from 1995 onwards?"

Now there's a question…

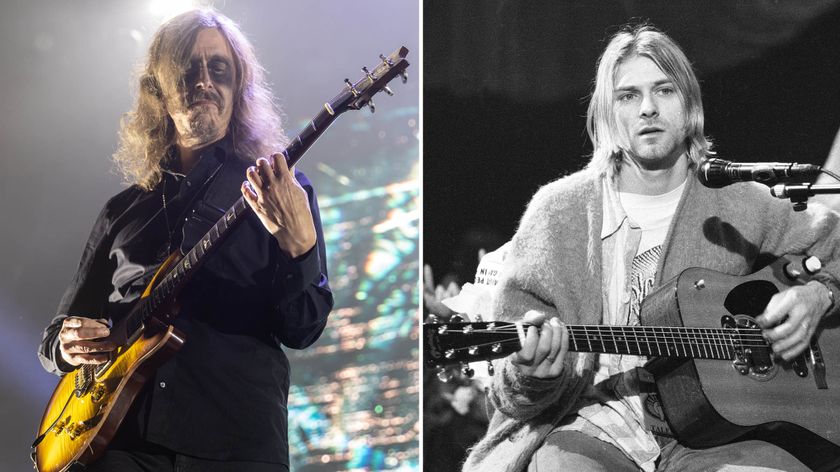

“I’m a Nirvana fan, but it was just a regular guitar to me”: Opeth frontman Mikael Åkerfeldt left unimpressed by Kurt Cobain’s “haunted” Martin acoustic

“Boy, he’s a weird guy. He’s got one orange sneaker, one red sneaker”: Gene Simmons on Ace Frehley’s memorable audition for Kiss

Most Popular