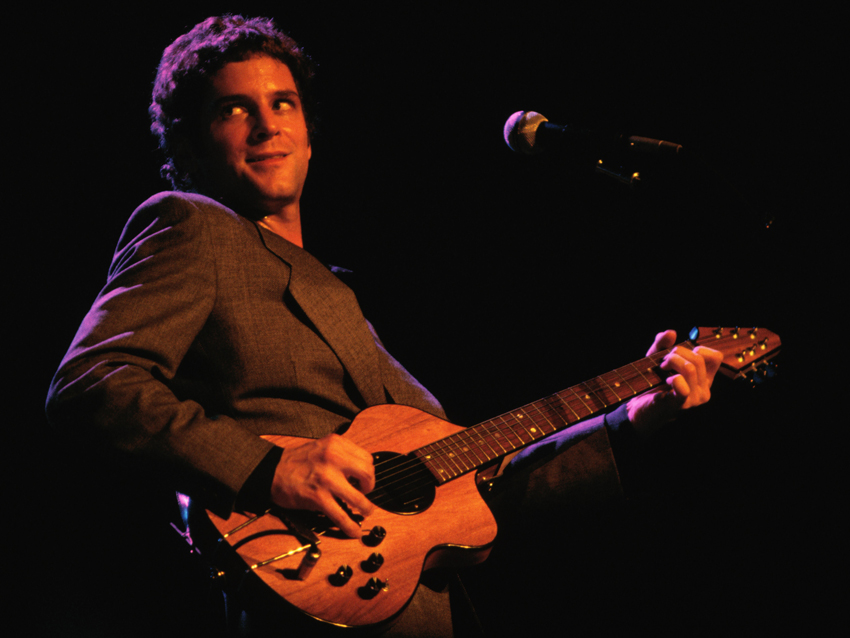

Lindsey Buckingham hits all the right notes on his brilliant new solo album, Seeds We Sow. © Kabik/Retna Ltd./Corbis

Since 1979, on Fleetwood Mac's masterpiece Tusk, Lindsey Buckingham has spent considerable time recording on his own in his home studio. On his vibrant, luminous new solo album, Seeds We Sow, the musician takes the DIY approach one step further: producing, engineering, singing and playing every instrument on all but one track. He's even releasing the record himself.

"There can be feelings of isolation when working alone," Buckingham admits, "but it's a good isolation. It's very meditative, much like painting. People who paint are usually pretty isolated. It's a solitary pursuit, but it lets you get one-on-one with your canvas."

Seeds We Sow is Buckingham's sixth solo album, and true to form, it's a compelling, wholly original rendering of shadows and light, cries and whispers. Whether pensive or blissed-out, rocking impulsively or examining the human spirit, the guitarist fuses his irrepressible, idiosyncratic songcraft with waves of breathtaking vocals and luxurious, fingerpicked guitar patterns into something that's become a rarity in modern music: a sublime, top-to-bottom, soul-nourishing experience.

A few weeks into a 50-city theater tour, Lindsey Buckingham sat down with MusicRadar to discuss Seeds We Sow. In addition, the Rock Hall Of Famer talked about his approach to guitar playing, the advantages of home recording, loving The Rolling Stones, his work with Fleetwood Mac (expect to hear from them in 2012!), and some of his essential guitars.

(By the way, be sure to check out the exclusive video on page two, during which Buckingham expounds on the recording of Seeds We Sow and takes us on stage and backstage during a performance.)

In much the same way that great method actors don't "act," but rather they "behave," your work on Seeds We Sow goes beyond craftsmanship.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Well, that's good, I guess. [laughs] You want to be good at your craft, but you don't want to wear all the construction on your sleeve. If you're doing that, you might not be doing your job. Over the years that I've been doing this, and particularly since I started making solo records with greater frequency, I've looked into whatever my center is, which is the guitar, and I've looked into the emotional side of that, as well. That's really the idea: touching on what's essential, both musically and lyrically.

"I do think my lyrics have gotten...not necessarily more poetic, but more open to interpretation; they're less literal. All of that fits into what you're saying."

You've had a home studio for many years now. What are some recent changes you've made to your setup?

"Not a lot, really. I still have an old, unautomated console that I got in the late '80s. And I still do a lot of work on an old, reel-to-reel digital machine. I just love the VSO. [laughs] Not that you can't do that in Pro Tools - you certainly can. I do have Pro Tools, but they seem to come later in the process.

"My setup is not that different from what it's been for a while now. What happens is, you find a way that works for you, and at that point… You know, there's an adage that would apply here: 'It ain't what you got, it's what you're doing with what you got.' [laughs] It's true."

On the new album you do a beautiful version of The Rolling Stones' She Smiled Sweetly. You've covered them in the past. And even Go Your Own Way owes something to the Stones -

"Yeah, the drum pattern on that. I wanted Mick to do something like Street Fighting Man, and he put his own thing to it. But that's right, exactly."

So besides the obvious - that they're a great band - what is it that you like about the Stones so much?

"Well, I think they're a band that has held up rather well, particularly the period that I cover, which is when Brian Jones was at his peak, right before he started to go downhill. He was starting to bring in European sensibilities that kind of balanced out the Chuck Berry-isms of Keith. I always thought there were a lot of undiscovered gems on albums like Aftermath and Between The Buttons.

"Everything else on this album, all of the original songs, I wrote them out as snippets of ideas right before I went in to start the actual recording. She Smiled Sweetly was the only thing I had recorded previously; it had sitting around for a while, waiting to find a home. It seemed somehow appropriate to end the album with it. It turned out pretty nice."

Stevie Nicks has said that, given the chance, she would have joined Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers. Conversely, would you have joined the Stones had the situated presented itself?

[laughs] "That's an odd question! Hmmm, well, that's sort of an odd thing for Stevie to say, too. I guess she was just looking at bands she likes. The Stones…uh, sure! [laughs] What a great situation. They have a raw, primitive approach to music, and I relate to that - I'm kind of a refined primitive myself, having never been taught music.

"It seems like a thought that is so far-fetched. Probably the Tom Petty thing, too. I can't imagine Tom asking a woman to join his band; he's got such a guy thing going on. As for me joining The Rolling Stones…it's a nice thing to think about." [laughs]

You first demonstrated your fingerpicking technique on your initial albums with Fleetwood Mac. It's really developed over the years, into a rolling style - like a waterfall of notes. The title track, Seeds We Sow, is a fingerpicking extravaganza!

"Why, thank you. Sure, you can look at songs like Landslide and Never Going Back Again for that. On Never Going Back Again, I'm sort of enhancing the basic folk approach. Over time, I've developed it and tried to make the rhythms more sophisticated. Big Love was the song where I really started doing it on stage to such a degree. With that, a light bulb went off over my head and I started thinking, Hey, I've really got to look at this as being one of the mainstays of my style.

"It has become more rolling. I seem to keep gravitating back to some sort of 6/8 time signature. It's like a measure of four over a measure of six as far as my picking is concerned, but it's only revealed as 6/8 when my singing comes in. It's an area of playing that I've become very interested in and tried to expound upon, especially since I've done more and more solo albums. It seems to be working out."

Playing one of his Turner acoustics at the Sundance Film Festival in 2007. © Scott McDermott/Corbis

Your vocal performance on the title track is quite dramatic, especially at the end. Is singing a catharsis for you, a release?

"Sometimes. Yeah, I think there's some songs on new record where it's releasing something, where it's about moving on to the next phase. On the song Seeds We Sow, it's very much a comment on where things are going in the world, but in sort of a schizoid way it comes back and examines those same tendencies in a relationship."

From a production standpoint, Illumination and That's The Way Love Goes recall the quirkiness of the Tusk album. Do you have any kind of production aesthetic?

"Oh, God! I couldn't put any kind of label on my production aesthetic. [laughs] Certainly, I feel that this album has a good representation of things that are living in the left side of my palette, and it's got some things that move more to the right.

"You've got songs like End Of Time which are more, for lack of a better term, kind of 'Fleetwood Mac-y,' and that's an emotional tone that's just as valid as anything else. Yeah, you want to keep exploring areas that are both familiar and unfamiliar. What I like about this record is that it represents pretty well the musical landscape I have going, from left to right."

In a recent interview with Guitar Aficionado, you likened working in Fleetwood Mac to big-brand movies like Pirates Of The Caribbean, that it wasn't "chancy" -

"Here's the thing: I think it could be chancy. Sometimes it is quite chancy on a political level. But I think that you've got to understand that the collective politics tend to align themselves with what Warner Bros. or any record company might want us to do, which adheres to 'the brand,' such as it is.

"You know, we went out last year and toured without a new album, and it was actually a great deal of fun because we've got this big body of work that stands on its own. There's a freedom in knowing that and feeling that and being able to perform that.

"But I think the collective wheel of Fleetwood Mac tends to want to take less chances, certainly less than I would on my own. That's one of the nice things about having both things, Fleetwood Mac and a solo career. I guess you can look at Fleetwood Mac as the Pirates Of The Caribbean movies and my solo career as indie films."

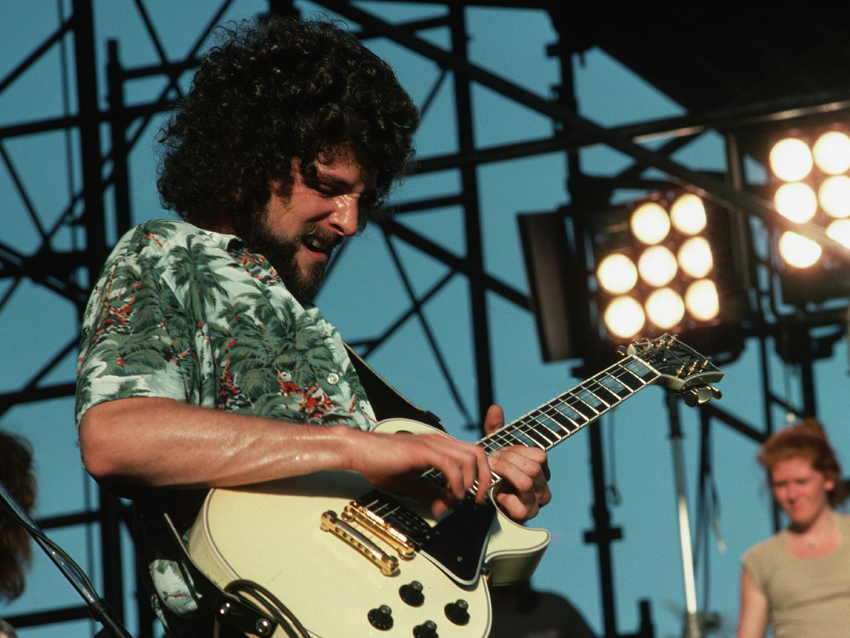

On stage with Fleetwood Mac in 1980, with one of his first Turner electrics. © Neal Preston/CORBIS

Right. But at this point in you career, both solo and in Fleetwood Mac, surely you can do whatever you want.

"Yes, if you step back and look at that, sure I can. But what's interesting about Fleetwood Mac is that we're a band of people who have never wanted the same things. In a weird way, we probably don't even belong in the same band together. For whatever reasons, we can't always say, 'This is what we want, and here are the reasons.'

"If I'm not off doing my thing, then Stevie's off doing her thing. It probably drives John and Mick crazy. And, you know, I think there should come a time when we can just be Fleetwood Mac for a longer period of time, where we can connect the dots, each one of us. I'd love to see that happen.

"If we can do that, then maybe we will be able to, as you say, 'do what we want.' But what I want isn't necessarily what Stevie wants or what John wants or what Mick wants. It makes it difficult on a political level; it also makes it interesting."

If working on your own is, as you say, akin to painting, can't collaboration in a band context be equally challenging and rewarding artistically?

"Well, sure. And it is. There are big differences, though. For one thing, when you're working on your own, you can start with the smallest of ides. You don't have to go in with something as fleshed out as you would if you're working with others. You can just go in and throw the paint on the canvas, and the work will evolve and take on its own life and lead you in directions you weren't expecting. There are definitely opportunities for surprises and spontaneity.

"You'd think that spontaneity would only go with the collaborative thing, but that's not always the case. Collaboration can be spontaneous, but so can working on your own. It's a process that's served me well for a long time. I seem to be getting better at it, so why stop now?"

Where do you find inspiration nowadays? Is it a different experience than when you were younger? Do you have to work harder to find it?

"I think that when you're quite young, you tend to be part of a community of people who are aspiring to something similar as yourself, or they share the same sensibilities, and because of that you have conversations and exchange ideas - that's where the inspiration comes from.

"The older you get and the more you find your own style, the less important that becomes, because you're not looking for things to draw from so literally. That communal exchange falls away as youth recedes.

"The things that inspire me are a certain way of thinking. I can be in the car and listen to what my daughters want to hear, which will be the station that plays Katy Perry and Lady Gaga or whoever, and that's all very well and good. But I can go and find a college station on satellite radio and find stuff that isn't getting heard by a broad range of people. Usually they'll be groups or people that I can relate to for the reasons they're making music.

"Some of these acts have broken through: Arcade Fire, Phoenix, Dirty Projectors, Vampire Weekend - there's a lot of groups out there that are making really good, smart music. It's about the spirit behind it all."

Buckingham, in the first wave of Rumours glory, playing a 1974 Les Paul in 1977. © Neal Preston/CORBIS

Rick Turner guitars have been your go-to instruments for a while now. What do you like about them so much?

"Before I joined Fleetwood Mac, my electric guitar of choice was a Fender Stratocaster - I think a 1963 model. The reason why I liked the Stratocaster was because the sound of it was very suited to fingerpicking. It's very percussive and cuts through other instruments.

"Of course, that tone didn't suit the pre-existing sound of Fleetwood Mac. From the rhythm section of Mick and John and the guitarists who had played on the records, it was a fatter sound. When I joined the band, I had to start using a Les Paul, which wasn't ideal for a fingerpicking style.

"Rick had been making John's basses, and after getting to know him for a while, I asked him to make me some sort of a hybrid guitar, one which was like a Les Paul in that it was fat enough, but it would also have the percussiveness of a Stratocaster. This is the guitar he came up with, and it really works for me."

Do you have any other essential guitars?

"Yeah. I have an old Martin D-18 that I still use a lot. I got that when I was about 19 years old, up in the Bay Area. I use that in the studio quite a bit. I love the baby Taylors. If you get a good one, they record very well. Also, there's the Stratocaster that I mentioned.

"Let's see...what else? There have been guitars I've played and they've served me well, but for whatever reason, I've had to use other guitars. You know how it is: your needs change."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track