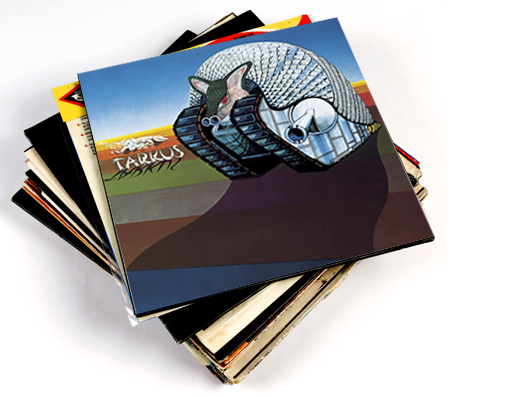

Interview: Keith Emerson talks Emerson, Lake & Palmer's Tarkus track-by-track

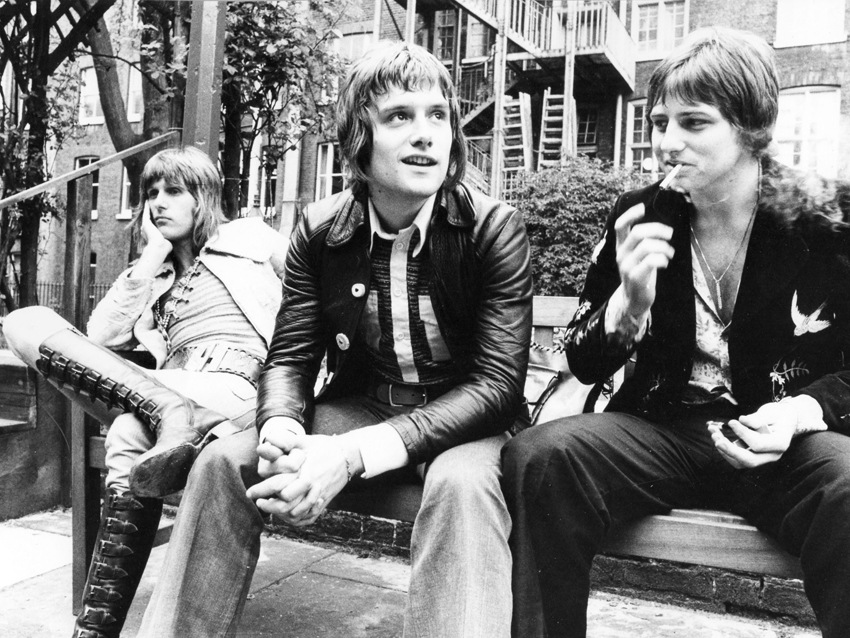

Although their relevance would eventually come under fire by the likes of the Sex Pistols and The Clash, progressive-rock pioneers Emerson, Lake & Palmer, from the very start, displayed the very same kind of musical ideology that defined punk. “We were very defiant,” Keith Emerson says. “We did what we wanted. It wasn’t about having hit singles or being on the radio, although we did manage to get a lot of radio play and have singles. We listened to so much and brought it all into what we were doing.”

When the trio of Emerson, Greg Lake and Carl Palmer entered London's Advision Studios in January 1971 to begin work on their sophomore album, their debut disc was making waves as a crafty, ambitious bit of “art rock.” Pressure was on the band to make an even bigger statement statement with their follow-up, but Emerson says that Tarkus took shape with no real agenda.

“There wasn’t this grand concept or anything like that,” he says. “We’d already made the record with the dove on the front, and now we were making another with an armadillo on it. In many ways, I suppose we were still learning how to be a band."

Part of that learning curve involved playing records for one another and sharing disparate influences. Before sessions began, Emerson would drop by Lake’s apartment, where the bassist-guitarist and singer would play the keyboard ace tracks by Simon & Garfunkel, Joni Mitchell and Cannonball Adderly. “It was all very interesting,” says Emerson. “After hearing what Greg had, I’d play him some Shostakovich. Somehow, we managed to put it all together. We were pretty happy doing so.”

However, that spirit of harmony and adventure hit a wall over the 21-minute title piece, a seven-movement suite that Lake couldn’t find much joy in. “It provided for a lot of angst,” Emerson says. “Greg wasn’t too happy with it. He thought it was too much of a classical piece and that it was too similar to what I had done with The Nice. Carl liked it, though. As a drummer, Carl was always willing to face a challenge.”

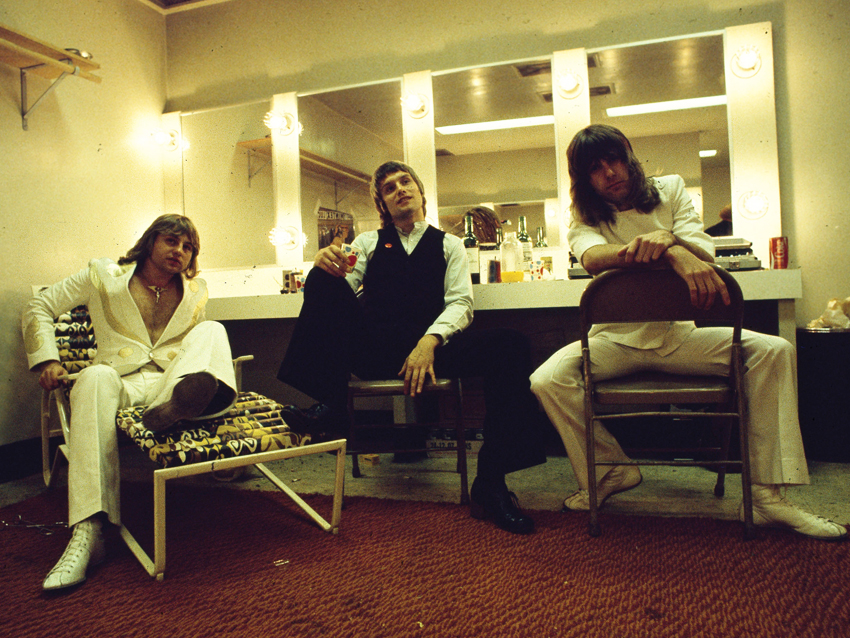

Released on 14 June 1971, Tarkus was a watershed moment in the burgeoning progressive-rock movement (“we never used that term, ‘prog rock,’” says Emerson. “I don’t know where that got started”), hitting number one in the UK and reaching the Top 10 in the States. “It sounds amazing now, going number one,” says Emerson. “At the time, we couldn’t really celebrate – we were too busy. We were touring like crazy, and if we weren’t on the road, we were in the studio working on things that were even more demanding. This was a period of very intense creativity.”

Recently, Razor & Tie reissued ELP’s debut album and Tarkus as lavish three-disc sets, remixed by Porcupine Tree’s Steven Wilson, both of which contain previously unheard outtakes. On the following pages, Emerson recounts the writing and recording of the original album, a work that he sums up as “pretty incredible. You listen to the record and you go, ‘Oh, that’s them. That’s ELP.’ Seriously, I wouldn’t want to change one note.

“It offers a lot for the advancement of musicians. If anybody wants to get into progressive rock music – and God forbid anyone wants to [laughs] – it provides the elements. You’ve got a lot going on with Tarkus.”

Tarkus

“It’s an epic, isn’t it? There’s one part in the piece where we’re playing in 10/8. That was Carl’s doing. Even The Beatles had used time signatures in 7/8, so I guess that going somewhere like that wasn’t too unusual. But Carl was very forward-looking in how he wanted to push time signatures. He was sitting backstage with a practice pad, and he started hitting out this 10/8 rhythm. It sounded right, so that got me to writing Tarkus.

“The writing was very painstaking. The whole thing was composed on an upright piano in this little apartment in London I was living in at the time. I wrote it out on manuscript, too, which not many people do. I have to say, it wasn’t intended to project any pianistic bravados, like, ‘Oh, my God! This keyboard player is fantastic.’ Nothing like that. I was just trying to get a point across.

“It starts off with The Eruption, which was the first thing that got Greg’s attention. He said, ‘Yeah, well, that’s a nice prelude to a song.’ But as an entire piece, he wasn’t very enthusiastic. It took some convincing to get us to do it. When it came time to produce it, that’s when Greg went along with it, and by then he’d stuck his producer’s hat on, so he was really OK with it. The rest of the piece came together quite easily, actually. Once Greg and Carl got the 5/4 down, and then we had the 10/8 section, everything else flowed.

“We rehearsed it for a week or so in the studio. Greg and Carl don’t read music, so we ran it down quite a bit. They formulated it and memorized it. Sometimes we rolled tape, just in case we got something worth keeping. We ran it down live as a trio, got a take, and then we listened back in the control room for parts that needed overdubs. ‘What about a gong here? What about a portamento sweep there?’ Greg and Carl had lots of cool suggestions.

“It’s a well-composed piece. I made sure that the fourths and fifths were working together. There’s a good sense of continuity to it. I was searching for what one of my heroes, John Coltrane, wanted to create – walls of sound. I thought, I can dig that, but I’m going to go another way to get that across, with electronics and the Moog synthesizer and everything else.

“I had the Moog modular synthesizer for this, which I’d started using in 1969. It’s being renovated in California right now. It’s a killer, let me tell you. Quite an instrument, the Moog.”

Jeremy Bender

“I was messing around with the chord progressions to Oh! Susanna, and I played it on a honky-tonk piano. I added some fifth root chords to it, and everybody thought that was pretty cool. Then Greg came up with the words: ‘Jeremy Bender was a man of leisure, took his pleasure in the evening sun.’

“I have no idea where those lyrics came from. But the title, the name ‘Bender’ – back in those days, that was a guy with gay attitudes. I didn’t think much about that; I was just happy to get some words up so I could play that honky-tonk piano.

“It’s sort of Floyd Kramer, the piano style. He was a great player. So it’s sort of me doing Floyd playing Oh! Susanna, if that makes any sense. We all thought it was a fun song. It lightened everything up.”

Bitches Crystal

“That was a rather inspired idea of doing boogie-woogie in 6/8. I suppose I was drawing upon a strong Dave Brubeck influence. I was very fortunate to have met the guy and also his sons – terrific people.

“We didn’t have much trouble with the song. We went in with a pretty strong idea, practiced it up to the point where we know what we were doing, and ran it down. The music is pretty hard in spots. We attacked it. Greg wasn’t as entranced by Brubeck as I was, but Carl was very taken with Dave’s drummer, Joe Morello. You can hear that kind of feel here. Carl knew what he was up to.”

The Only Way (Hymn)

“I’m on the pipe organ. What a brilliant sound. I found this church organ, and I learned some Bach piece on it. It’s a whole different approach playing a pipe organ, particularly when it comes to the feet – I’m not Fred Astaire on the foot pedals.

“I got around that, though. The piece is in F, so I just planted my foot on the F pedal and played everything else like I was doing the piano. But it’s kind of weird, though – you get this delay. That took a while to get used to. I worked a little Bach French Suite in D minor in there. I was quite pleased.

“We recorded it with a mobile recording facility. There was no way to bring the pipe organ to Advision Studios, and of course, there were no computers and samples and everything that you have now. But it worked out well. Greg and I realized that we had a song, and then he went off to work out the lyrics.

“I have no idea about words. I remember Greg going into the vocal box to sing it, and Carl and I were sitting in the control room wondering how it was all going to come out. Suddenly, we hear Greg sing, ‘Why did he lose six million Jews?’ That kind of halted the proceedings for a while. We had to consider that. ‘Do we really want to go there? This is too heavy… ‘ But Greg was like, ‘This is what it’s about.’”

Infinite Space (Conclusion)

“It’s pretty much a piano solo piece. I was using a Bechstein, a seven-footer. After the profound words that we’d just had, we needed something a bit more laid-back. It’s a good time signature. It wasn’t me trying to be clever; it just seemed to work.

“I thought there could have been a vocal over it, even if the song was a bit Rio De Janeiro-ish in feel. World music was in the back of my mind."

A Time And A Place

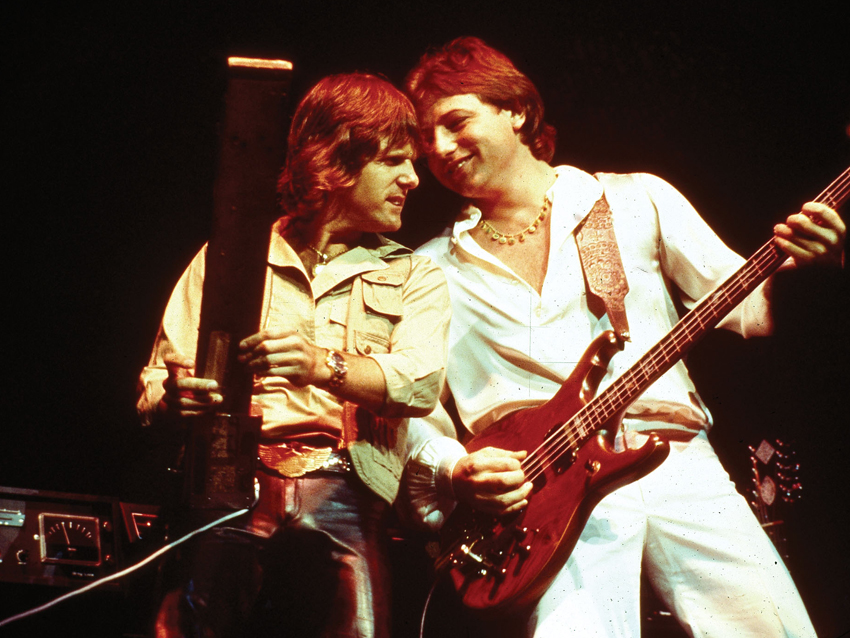

“There was some sort of Led Zeppelin influence going on with this one. ELP and Zeppelin rehearsed in the same area back then. I know I was listening to a lot of Zeppelin. Black Dog was a really good one. Jimmy Page was a mate of mine. Greg didn’t care about Zeppelin that much. If he did think about them, he was thinking about how much money they were making.

“I play a lot of unison lines in the song, and they work out well and create a lot of power. The recording went very smoothly. Once we got that main long piece down, the Tarkus epic, everything else was fairly easy. We probably did about three takes of A Time And A Place and that was it.

“There’s good keyboard sounds here. I was sticking with the Moog and the Hammond B3. Later on, I went with the Yamaha GX-1, which contributed greatly to our signature sound on tracks like Fanfare For The Common Man.

"I never mentioned being influenced by Zeppelin to Jimmy Page. When you meet up with people socially, you never get into that stuff at all. It just doesn't come up."

Are You Ready Eddy?

“That became our catchphrase during the time ELP were recording at Advision. We’d be practicing and perfecting what we were going to be doing, and our engineer, Eddy Offord, would venture outside and leave us be. When he came back, he’d go into the control room and we’d say, ‘Are you ready, Eddy?’

“The track is fun. We were having what you’d call a ‘wrap party.’ [Sings] ‘Are you ready, Eddy, to switch those sixteen tracks on/ Eddy edit, Eddy-eddy-edit.’ [Laughs] Greg and Carl and myself grew out of that time of rock ‘n’ roll, lettin’ your hair down and all that. We were a fun band, although we did write some serious shit. We definitely had a sense of humor.

“I might have messed up a bit on the tuning. I was always drawing things on the piano hammers and what not. But the spirit is there. It was a one-off take and we were done with it.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“I’d be running from the studio to other speakers in the house, basically going insane trying to get mixes to sound correct”: Ezra Collective’s Joe Armon-Jones on why he created his Aquarii Studios and his dub-influenced mixing technique

“I haven’t been able to see the performance, but I have enjoyed it”: Elton John tells audience at Devil Wears Prada premiere that he’s lost his sight

“I’d be running from the studio to other speakers in the house, basically going insane trying to get mixes to sound correct”: Ezra Collective’s Joe Armon-Jones on why he created his Aquarii Studios and his dub-influenced mixing technique

“I haven’t been able to see the performance, but I have enjoyed it”: Elton John tells audience at Devil Wears Prada premiere that he’s lost his sight