In his nearly 50 years in rock 'n' roll, Graham Nash has performed for audiences of all shapes and sizes, from intimate coffeehouses to the panorama that was Woodstock. But of the current Crosby, Stills & Nash tour, which comes to a close this Monday (22 October) in New York City, Nash says that "a different energy is out there. We're doing incredible business. The shows are packed. I don't know why, but people seem to be appreciating us more. Maybe they're sick of Britney Spears or Lady Gaga. We're reaching people's hearts. It's beautiful."

For the band's final show of 2012, CSN have planned something special: they'll perform their 1969 debut album in its entirety. The five-night Beacon Theatre run is just part of a triumphant week in NYC for Nash, as it coincides with the opening of The Art Of Graham Nash, a three-week exhibit of the musician's photographic images and original pastel pieces, at the ACA Galleries.

Recently, MusicRadar presented part 1 of an extensive interview with Nash, a wide-ranging conversation in which the two-time Rock And Roll Hall Of Famer held forth on topics ranging from CSN's failed attempt at working with Rick Rubin to how Nash came to leave The Hollies and went on form a different sound with David Crosby and Stephen Stills. In this, the conclusion of our chat, we pick up where we left off:

You split The Hollies because they didn't like the songs you were writing. Why didn't they like them?

"I'd written a song called King Midas In Reverse. I thought it was pretty decent, and we made a pretty decent record out of it. It didn't do so well commercially, and after that they started to not trust my musical direction. It all started to crumble after that song. At the time that I felt a pulling away from The Hollies, David came into my life and took up that slack."

How did it feel for you to come to the US and create a sound that was, for lack of a better term, very "American"? CSN certainly wasn't a very British sound.

"Now, I have to keep The Beatles out of this, because they were very proud of their Liverpool accents, and they didn't ever want to disguise them. But most bands sang in a very mid-Atlantic accent. You couldn't tell from The Hollies' records where we came from. You could with The Beatles. But what I did with David and Stephen felt very natural. It sounded great!" [Laughs]

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

With Déjà Vu came the addition of Neil Young. How did that change the group dynamic?

"When we finished the first record, we realized two things: One, that we had a big hit on our hands, because everybody was just wiped on the floor with it, and two, that we would have to go on the road. Stephen played every instrument on that record except for the drums and the acoustic guitars that David and I played on our songs. He played bass, he played organ, he played lead guitar, he played rhythm guitar, he played everything. Captain Many Hands we called him.

"You can't do that live. You need help. So who would we get to help? We talked to Hendrix, we talked to Stevie Winwood, we talked to a bunch of people who we thought might want to join. They didn't want to do it. Ahmet [Ertegun] said to Stephen, 'Hey man, maybe you should get Neil.' Stephen is ready to strangle Ahmet, like, 'Ahmet, I've just been through two years with this crazy fucker. What do you mean we gotta get him back?' But Ahmet said, 'Hey man, it might work, it might work.'

"At first, I didn't want to do it. I didn't want Neil to join the band. I knew he was a great songwriter, because I'd loved Expecting To Fly. I thought it was a brilliant piece of songwriting and recording. But we had created this sound with our voices, and to add anything more to that would change it radically. So I didn't want to do that at first, but I realized that Stephen needed somebody to spark off of and play the guitar, because that's who Stephen was. He loves the challenge of two stags facing off - he'd been doing that in the Springfield.

"I didn't think we needed anybody else, but I said, 'OK, if you're so adamant, I have to meet this guy.' I knew him as a songwriter, but I didn't know if I'd like him, if I could hang with him - all of that stuff. So I had breakfast with Neil on Bleecker Street, and after that I would have made him king of the world. [Laughs] He was funny, he was dry, he was dedicated, and he was a special man. I realized that right off."

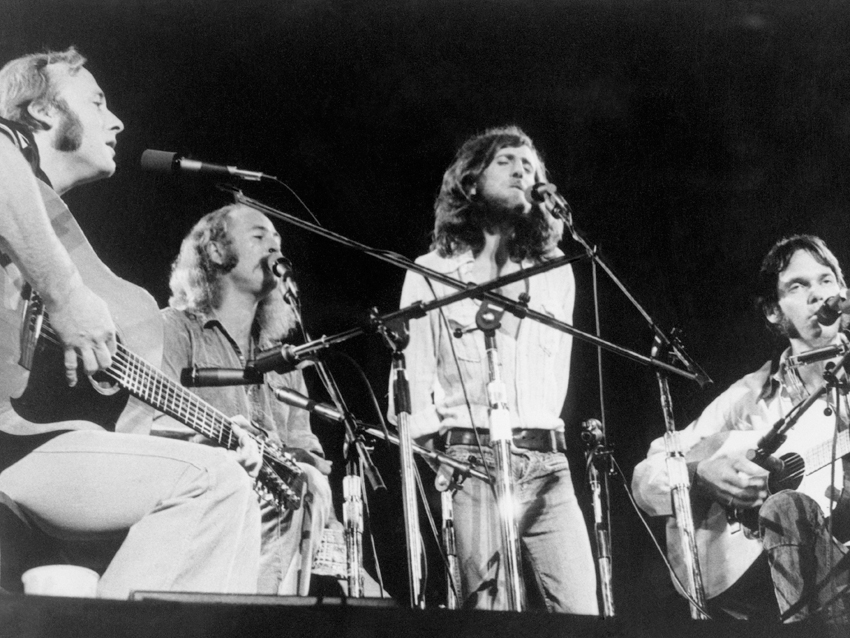

CSN&Y play Seattle, July 1974. "The drugs and the distractions - it was crazy." © Bettmann/CORBIS

How did you demo songs like Teach Your Children and Our House? What was your process? Did you make tapes?

"Yeah. I used whatever was around. I have a tape of Teach Your Children that I did in late '68, just a little groovy two-track recorder. There were no Walkmens or anything like that back then. Or you'd go into the studio, and before a session started you'd say, 'Just turn on the machine. I've got a song here…' Personally, I love demos. There's a thing in the recording business that musicians go through called 'chasing the demo.' Very often, you get up at three in the morning, and you put everything into that idea. It's hard to get back to that. But I love demos."

Dallas Tayor did some amazing drumming on Our House. Did you have the drum arrangement worked out, either on the demo or in your head?

"I very rarely tell musicians what to play. My father taught me something at a very young age: 'Don't buy a dog and bark yourself.' Let people do what they do. Our House started on the piano, but I played it in such a way that you could overdub the drums to it. Dallas Taylor was a good drummer. He didn't make it as far as Neil was concerned, but who does?" [Laughs]

With Déjà Vu, it's been said that the band didn't record much together - you worked separately a lot.

"There were a couple of things happening with that record. The first Crosby, Stills & Nash record was full of joy. Déjà Vu is quite dark, and there's a reason for that. During the first album, we were all in love. David was in love with Christine [Hinton], Stephen was in love with Judy Collins, I was in love with Joni [Mitchell]. Everything was rosy and fantastic. By Déjà Vu, Joni and I had split up, Stephen and Judy had split up, and Christine had just been killed. It was all dark.

"Add to that the amount of drugs we were taking, the amount of cocaine we snorted, and add to that the individualism of Neil Young. The only track that I remember we played on together was Helpless, and it was only at three in the morning, when we'd run out of cocaine and we could play slow enough for Neil to dig it. Neil would record in Los Angeles, then he'd bring the recording to the studio and we'd put our voices on, and then he'd take it away and mix it himself.

"Neil's a strange energy. He brings a darker edge and a more realistic edge to our music. You have to be totally on your game because Neil doesn't fuck around. It did fit, though. Déjà Vu is a pretty fun album."

You guys were all friendly with Jimi Hendrix. I know Stephen played guitar with him - did you ever?

"Oh, no, no. I would never play guitar with Jimi [laughs]. But I hung out with him. I used to share an apartment in London with Mitch Mitchell, and I got to hang with Jimi a lot. By the way, nobody could ever beat Jimi Hendrix at Risk. No one. Nobody ever. He would drop acid and play Risk, and he was still unbeatable.

"He was very different from his image. He was a very serious cat - very humble, but very serious. He realized he was trapped. He was trapped into playing the guitar behind his head, playing with his teeth, sticking his tongue out, Foxey Lady and all that. He had created this sexual image that… Who the hell could live up to that constantly?

"I first met Jimi in '65. He was in Little Richard's band at the time. This was at the Paramount Theatre in New York City, the Soupy Sales Easter Show. I'll give you a story from my book: When we came to America for the very first time, we went to the Paramount Theatre where the gig was, and we thought we were going to do our set - 45 minutes of dynamite. 'Which two songs are you were doing?' we were asked. We were like, 'What? Two songs?' But there were 12 other acts on the bill, five shows a day - two songs. So that was a shock.

"Little Richard closed the show, and we would watch him from the side of the stage. One night I heard this argument before they went on: 'Don't you ever fucking do that again! I'm Little Richard, the king of rock 'n' roll, you fucking guy! Stop playing your fucking guitar behind your fucking head!' And he was yelling at Jimi. It was this argument as they got in the elevator to go up. The volume decreased as they went, but you could still hear them arguing. I can hear it now. So that was Jimi. It was obvious he was a talented guy."

After Déjà Vu, in solo projects and as a band, you guys started getting pretty political in the songs: Chicago, Immigration Man, Ohio…

"Well, is it political or is it human? We don't think we're a political band; we think we're a fucking human band. When you bind and gag and chain a man and call it a fair trial, that's not political - that's a human story. You slaughter four kids because of their God-given right to protest what their government is doing, that's not political - that's a human story. People say, 'Oh, it's a political song. It's a protest song.' It's not - it's fucking human."

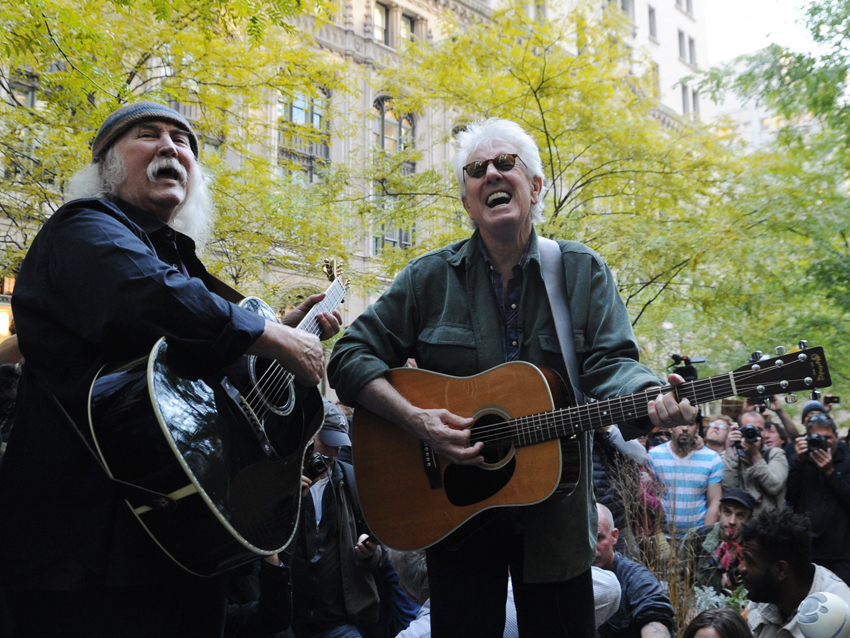

Crosby and Nash take it to the street, as in Occupy Wall Street, 2011. © Stephanie Keith / Demotix/Demotix/Demotix/Corbis

The songs still resonate just as strongly today.

"Sure. You know, we killed our own single. We had Teach Your Children going up the charts, and then Kent State happened. Crosby called me up and said he'd booked a studio. 'Neil just wrote this song, it's fucking fantastic. Get down here.' Neil played me Ohio, and it was 'Holy fuck - fantastic.' We recorded it in an hour and a half, recorded Find The Cost Of Freedom in half an hour. Ahmet Ertegun was sitting right there. We mixed it, gave him the two-track and said, 'Ahmet, we want this out now.' Ahmet put up an argument, but we were firm. Twelve days later, we put it out in a single sleeve with a copy of the Constitution that had four bullet holes on it. Is that political? No. But people say it is."

After the success of Déjà Vu, there was a lot of tension in the band. What was at the root of the problems?

"Drugs and ego. We had plenty of both. Lots of cocaine."

But lots of bands need five or six albums before they break up - you guys were already there by 4-Way Street.

"Yeah. We're not like other bands. [Laughs] It was hard getting us together, too. We were popular, we were in-demand - trying to get our schedules together was not easy."

Since Déjà Vu, you've only done two albums as CSNY - Looking Forward and American Dream. What are your thoughts on those records?

"It's always fun to make music with Neil. It's different, but it's always fun. It's always more difficult, and the problems are exponential. Crosby always says, 'It's like juggling nitroglycerin - everything's fine until you drop one.' I love American Dream. There's a couple of songs where I think Neil was placating Stephen somewhat. A couple of songs I wish weren't there, and a couple I wish were there.

"Looking Forward is a great album. CSN were in the studio, and Neil came in one day when we were playing a certain piece of music. 'I love that. What else you got, man?' he said. We played him the other tracks, and then he pulled out one of his songs, and we were off and running. That's how fragile and solid this band is."

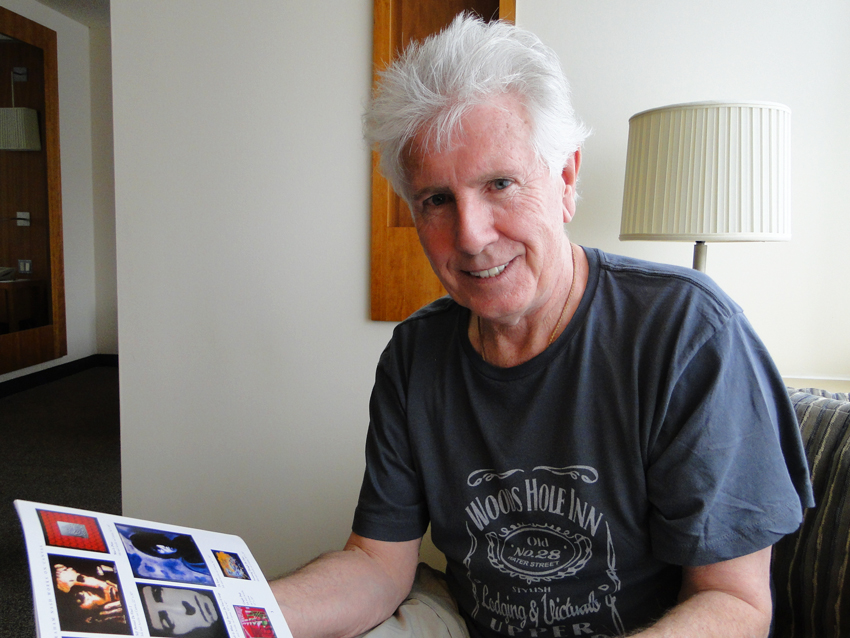

Nash checks out a catalogue of one of his recent art exhibits, July 2012. © Joe Bosso

Lastly, let's talk about your photos and your art - you're having exhibits.

"It's pretty cool. I've been a photographer all my life. During the 1974 stadium tour with CSNY, it was so crazy with the drugs and the distractions - it was crazy. To balance it out, I started to draw in this book. I was still partaking in the madness, but then I'd retreat and I'd draw. I put the book away and forgot all about it.

"Two years ago, I found it and some other drawings. I hadn't seen them in so many years. I have this company called Nash Visions - we were the first digital studio in the world. In fact, my first printer is in the Smithsonian - that's how important they thought it was. I did hi-res scans of my images, I had my company blow them up, and I painted them all. They're cool.

"You know, I'm on top of my music game, so why the fuck should I expose myself to criticism at this stage in my life? But I have no choice. I just do it. With art… I don't know what I'm doing. I've never had an art lesson. I don't know if this blue is supposed to go next to that yellow. I don't know if my brush stroke is any good. But I have to do it. That's just the way it is."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

![PRS Archon Classic and Mark Tremonti MT 15 v2: the newly redesigned tube amps offer a host of new features and tones, with the Alter Bridge guitarist's new lunchbox head [right] featuring the Overdrive channel from his MT 100 head, and there's a half-power switch, too.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/FD37q5pRLCQDhCpT8y94Zi.jpg)