Interview: Billy Gibbons talks ZZ Top's La Futura track-by-track

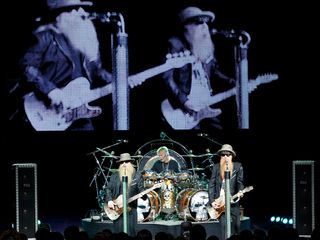

“A lot of producers would have the drummer come in on Monday, then they’d call the bass player in on Tuesday, the guitar player would show up on Wednesday and maybe the singer on Thursday," says ZZ Top guitar king Billy Gibbons. "When we got together with Rick Rubin, he said, 'My idea of ZZ Top is three guys playing together at the same time with the red light turned on.’ That sounded just right to us."

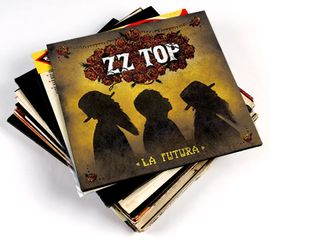

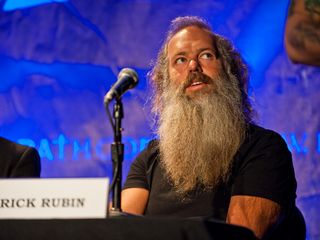

And so it was that for their forthcoming album, La Futura, their first full-length since 2003's Mescalero, that the "little ol' band from Texas" hooked up with the maverick producer. Gibbons and Rubin had rubbed shoulders before – their first meeting occurred 25 years ago during a rave at Knott's Berry Farm. Rubin had expressed interest in working with the trio over the years, but what sealed the deal, according to Gibbons, was when the producer said, ‘Hey man, I don’t have to rewire ZZ Top. My job is to make you guys work, work and work.’ And we said, ‘Superb.’ What Rick didn’t know was, that was music to our ears, because that’s what we enjoy doing the most.”

The recording process, which Gibbons admits was a "protracted affair," spread out over a nearly four-year period (during which time the band frequently broke for touring). The first session was an experimental jam in Los Angeles. "We weren’t writing or recording," says Gibbons. "This was Rick and a couple of engineers sitting behind the glass observing ZZ Top having fun. It was enough for Rick to start seeing the dynamic with the two other band members he didn’t really know."

Formal recording dates started later, at Shangri La Studios in Malibu, a facility close enough to Rubin's house that he could walk to it. "We still played as a band, and we got a chance to jam – the spirit was the same as it was when we started," says Gibbons. "Rick wanted us to work hard, but he placed an emphasis on us being casual and having a good time. And I found out that one of his high cards is patience. He was in no hurry to run the risk of having something half-baked. His attitude was, ‘It’s gonna take as long as it takes until it’s right.’”

After two months, the band had amassed roughly "20 CDs worth of starter piece material, songs, ideas and jam sessions," says Gibbons. It was then, before another touring phase was about to begin, that Gibbons and Rubin met on the pier in Santana Monica to talk about how to move forward. "Rick said, ‘Go back to Texas and draw as much as you can from our couple of months together. As you go along, we’ll keep a line of communication open to see if we’re getting somewhere.’ And that’s what we did. So I produced a number of tracks and we whittled them down to a nice, manageable batch.”

Gibbons acknowledges that some artists haven't always had a smooth ride with Rubin, and he admits that the stop-start nature of recording La Futura at times brought the band "to the brink of frustration," but he has nothing but high praise for the producer: “Rick was even gracious enough to give us fair warning right at the beginning," he says. "'I’ve been at this a while, but it hasn’t always worked out for me,’ he said. So he was upfront and said that at anytime, if we were finding stones in the pathway, that we should be men enough to address it. I took that so sincerely, especially since I knew that Rick was a fan. In setting up such a generous, two-way street, we avoided the pitfalls that have plagued him with certain artists in the past.”

The resulting album, 10 blazing tracks of gritty, funky and grinding blues that captures ZZ Top in classic, unadulterated peak form, blew Gibbons away when he first heard it. "We didn’t receive delivery of the finished piece until only two weeks ago," he says, "and I must say, we were quite pleased to hear the final version. What you suspect you’re hearing is what you’re getting: three guys playing the same three chords."

He adds, "It’s a funny thing – because the record took so long to reach its completion, we had forgotten some of its magical moments. And now we have to go learn it so we can play it live!"

As for the album title, Gibbons offers the following anecdote: “Rick said to me one day, “I’ve loved everything you’ve done, including all of those Mexican titles you’ve incorporated.’ And I said, ‘Well, Rick, you’ve brought us into the future.’ He looked at me and said, ‘How would you say ‘the future’ in Tex-Mex?’ And I said, ‘La Futura.’ And there it was - La Futura."

ZZ Top's La Futura will be released on 11 September. On the following pages, Billy Gibbons walks us through the bold and biting album track-by-track.

I Gotsta Get Paid

“A complex tale of musical alchemy. Call it the ghetto of the ‘50s meets the ghetto of the ‘90s, this incongruous coupling of ZZ Top and genesis of 25 Lighters.

“25 Lighters was a hip-hop chart topper 15 years ago, and it just so happened to be one of the tracks that our engineer, Mr. Gary Moon, was around for when he served as chief engineer at John Moranz Digital Services. That house specialized in rap and hip-hop clients.

“While our studio was being worked on, we took refuge in that house, and it was there that ZZ Top got friendly with a bunch of the hip-hop and rap guys. We were comparing notes and exchanging ideas; they were showing us beats and I was showing them guitar stuff. A great time was had.

“The name 25 Lighters comes from Houston ghetto slang for taking Bic Lighters apart, removing the innards and stuffing them with crack. You’d pass a dealer on the street and say, ‘Hey man, you got a lighter?’ The police would look the other way, ‘cause all you had was a lighter.

“We had some mainstays in the studio. There was a hobnailed Marshall hybrid, an old Marshall meets a later version cabinet. We had that, with own distinctive sound, and then we had a Magnatone. A friend of ours has picked up the banner and is re-introducing the brand, so we had a prototype. This thing is sizzling! It’s just wicked. The third secret weapon was from England, and that was a Blackstar. It’s a really good-sounding piece.

“For guitars, Pearly Gates is never too far from my hands. But there was a ’61 Les Paul in the SG shape. They call it a ‘transition model.’ George Gruhn had sold it to me when I was in Nashville. It’s an old guitar but in nearly mint condition, and let me tell you, it plays like butter.

“What we discovered is that when an artist covers a song, it’s called a ‘cover version.’ When an artist begins to modify and change it, after a certain percentage, it’s a ‘derivative work,’ and that requires the new version to be reviewed by the originators. If the originators like it, they can wave holy water over it and you’re good; if they don’t, you’re stuck.

“The two original performers, Lil’ Keke and Fat Pat, had passed away, and it was the last day to decide if we could do it that we tracked down the executor of the estates. We played him the track over the phone. ‘I don’t know if I can understand this,’ he said. ‘I’m going to put the phone to my little girl. She’s 14.’ When she heard it, she said, ‘Daddy, they’re playing your song!’ So the executor got back on and said, ‘Looks like you’ve got a winner.’”

Chartreuse

“We have a ZZ Top recording studio in Texas called Foam Box Recordings. It’s a humble little place to gather. After our months in Malibu, we reconvened at Foam Box to get some work done. Dusty asked me about the stuff I’d done with Rick and The Black Keys – we had seized a golden opportunity when we were all together – and he said, ‘Could we do one of those songs?’ And I said, ‘Why not?’ He happened to have one of the tracks on the CD player, but when he hit play it wasn’t The Black Keys, it was a completely different thing. It was a song that Rick had suggested we take a stab at, a Gillian Welch composition, It’s Too Easy – that’s the original title.

“It’s a very complex composition. Frank and Dusty kind of shy away from getting too academic; they don’t like to read charts. So they said, ‘Let’s just learn it.’ And I said, ‘Guys, this is complicated. It’s gonna take a lotta, lotta practice.’ They were like, ‘Aw, no, we can get through it.’ Well, it took two hours just to get the first verse.

“I said, ‘OK, we’ve got the first verse. Do you think we can take a stab at the next movement?’ This would be the solo section. Well, that was another two, two and a half hours. Now we’re getting weary. And what happened was, we learned the second movement and forgot the first! [laughs]

“We took five, everybody took a deep breath and came back in. This time, though, I said, ‘Instead of charging back into this hard-to-crack nut, Frank, give me a simple shuffle. Give me a good bluesy shuffle – Texi backbeat.’ Which he did, and I started into a guitar figure, and Dusty perked up. It kind of sounded a little like Tush. Dusty said, ‘I can do that. What key?’ And I said, ‘Key of C. Let’s fall in!' I’m getting the thumbs up from Mr. Moon, and we’re capturing this thing full-tilt.

“Only problem was, it was for 90 seconds. Frank and Dusty kind of threw in the towel and said, ‘You know what? We’re beat. Let’s pick this up tomorrow.’ Everybody folded the tent, Frank and Dusty split, and I went back into the control room. Well, wouldn’t you know, Mr. Moon looked at me and said, ‘Well, doggonit, we got it!’ I said, ‘What do you mean? We only played for a minute and a half.’ And he said, ‘That’s OK. All of the movements are intact. We can build a song out of this.’

“That was the first inkling that it was going to work, and it became the song Chartreuse. I stuck around and expanded on it. The next day the guys returned and they wanted to take another stab at it. Dusty said, ‘Well, what do we call this thing?’, to which Mr. Moon said, ‘Call it Chartreuse. First off, it’s a liqueur, and secondly, it’s an oddball color, and that’s what you guys are!’

“So it was born out of us trying to play the Gillian Welch song. There’s an abrupt ending, which is one of the few things a perfectionist might want to take issue with – ‘Can’t you guys get a more elegant stop point?’ But we left well enough alone and kept the excitement value.

“For the solo, I discovered that we had written a section in two different keys, and I don’t know how to play a solo that jumps from key to key without weeks of practice in order to get it polite. So, in short order, I knocked it out. It’s pretty well seamless. The bonus was playing the ’61 Les Paul that I got from George Gruhn. What an excellent-sounding machine.”

Consumption

“We played it live, however, the engineering squad – Rick’s guys and our guys – put their heads together and did what I call ‘subtractive mixing.’ They didn’t add anything, they were taking things away. It didn’t disrupt the flow, but it sounds like jumps here and pieces there, and the end result is a stop-start movement, one part being different from the next.

“There’s some funky effects going on in this thing, but boil it down and you’ve got a ZZ Top shuffle.

“The composition, in no small part, took its lead with La Grange being the inspiration. We played an old 1954 Fender Esquire, which is pretty close to the guitar we used on La Grange. There’s just something about the sound of a Fender that leads you into this kind of performance.”

Over You

“I collaborated with my buddy Tom Hambridge on this. He won a Grammy for Buddy Guy’s recent album [2010’s Living Proof]. To say that Tom is sort of mysterious would be an understatement. What a gifted, blues-based writer he is.

“We used Memphis as kind of our ground floor. The guitar is doing an arpeggiated, string-by-string pattern over the chord changes, and the piano is copying the arpeggiation but with a different inversion of the chord.

“Rick told me, ‘I didn’t know you played piano,’ and I said, ‘I don’t.’ [laughs] The engineer helped me as I put my hand on the first chord, and then we’d get through the second chord and so on. All in all, it oozes that bluesy thing.

“The day that I was set to get together with Tom, it was storming like you wouldn’t believe. ‘Are you sure you want to brave these waters?’ he said to me. But the dismal nature of that particular afternoon drove us into a very dark feeling. We envisioned this down-and-out guy, he’s sitting on a park bench, he’s lost his girl, nobody gives a damn about him, but he’s got the presence of mind to realize, ‘This is bad, but I’ve got to get over this.’”

Heartache In Blue

“I stayed in Nashville for quite some time, necessitated by my desire to see one of my good buddies, Mike Henderson, who plays at the Blue Bird every Monday night. Mike Henderson And The Blue Bloods. He’s a white cat, but you’d never know it.

“But that was only one night of the week, so I decided to look up some pals. One was Tom Hambridge, but another was Trey Bruce. Trey was running a studio on Music Row, so I said, ‘Hey, let’s make some noise.’ This is one of the tracks that we came out of it. What started as a few hours wound up being a few days.

“This is one of my favorites. For the harp, I called in the hired gun, my good buddy James Harman. He’d heard the composition, and when he was passing through Nashville he said, ‘Man, just give me a chance to answer those guitar riffs.’ By the way, that’s the Gretsch Billy-Bo I’m playing.

“Ironically, we didn’t get to record James until later, when he was passing through Houston. He nailed it in one pass. ‘I was taking notes when you were writing this thing,’ he told me.”

I Don't Wanna Lose, Lose, You

“That was the second composition that came out of the collaboration with Tom Hambridge. I went back to Malibu with Rick during the final two weeks of review. He and I both liked it. It was sitting there and Rick didn’t want to let it go – he liked it, but he couldn’t figure out what it needed.

“We were in the control room, we played it and played it, and suddenly I stumbled upon the lead line, ‘I don’t want to lose you.’ Instantly, we retitled it. I took a few minutes and rewrote the lyrics, and there you have it.

“It was funny, though, because I had to call my buddy Tom, who by this time was in Chicago. ‘Well, I trashed another one of our songs, Tom!’ [laughs] And he said, ‘Hey, if you trashed if like you did the other one, you’ve got my blessing.’

“Before cutting the solo, I had been listening to Keith Richards. I talked to him, and we were discussing songs that left him in mysteryland. One was a song originally done by Bo Diddley called Crackin’ Up. The Stones’ version is great, but Keith was talking about the eight bars, how Bo gets the guitar upside down and backwards and then magically gets out of it. Keith said, ‘It’s one of those happy accidents. I’ve been trying to do that for 40 years.’

“Two Stones songs have done that to me. There’s Start Me Up – it’s very difficult to find the downbeat in the intro until they finally kick it in – and the other one is a Keith solo song called Take It So Hard. Man, it’s so riveting!

“So it was a Keith Richards-inspired day of soloing, which means… it just happened!”

Flyin' High

“A good buddy of mine in Los Angeles, Austin Hanks, is a Southern boy, and I met him when he was working as a bartender in a famous tequila joint called El Carmen Tequila Cantina.

“Austin and I wrote a song that had that beautiful chorus section in there, but here again, it wasn’t ship-shape; it was kind of just in demo form. Well, lo and behold, Dusty is good buddies with Mike Fossum, one of the NASA astronauts. Dusty called me up and said Mike was getting ready to go up, and he wanted a ZZ Top song because NASA had given him permission to take an iPod with him. I said, ‘Oh, that’s interesting. Which one did he pick?’ And Dusty said, ‘He wants one of the new ones.’

“He asked me about the song that I had done with Austin, and I told him it wasn’t quite finished. Then I said, ‘Give me a minute.’ I called up Austin, and I said, ‘Let me have a chance to change some of the words. I’m going to call the song Flyin’ High. One of the astronauts is going up and he wants to take a ZZ song with him.’

“Austin thought it was a great idea, so I drove over, had some drinks of tequila with my good buddy, and there you have it. NASA did let Mike take the song up.

“I used Pearly Gates on the solo. There’s a fade-out on this version, but the one that was sent up into outer space was different. Remember the arrangement when NASA was working with the Russians? Well, on the version we sent into space, it collides abruptly with these two Russian cosmonauts talking. Somebody asked me, ‘What are they saying? I don’t speak Russian.’ I got a translator, and as it turned out, one of the cosmonauts was asking the other, ‘How in the hell do I get this helmet off?’”

It's Too Easy Mañana

“I said to the guys, ‘This was giving us trouble on the first go-round, but we can chart our way and navigate through the changes.’ We amended some of the words and kind of 'ZZ-fied' it a little bit more into our corner.

“Once it was done, it was one of the tracks that we were certain would get dropped. Never in our wildest dreams did we feel that it would make the grade. But Rick liked it. I think what might have been giving us trepidation was remembering the tough times it took for us to get the thing recorded in the first place. It was like, ‘Oh my God, not that again!’ [laughs]

“On the solo, I made some notes to the engineers to have a lot of fun riding the delay gain. The song is such a dirge, it just oozes. One of the things that changed our minds about the song happened when Frank’s boys asked him to play the album for them. This was, like, 10 days ago. They had heard the album once before. So he got to It’s Too Easy Mañana, and right as he was about to reach for the button to advance it, they said, ‘No, no, that’s our favorite song!’

“So that made us go, ‘Gee whiz, maybe there is something to it.’ It’s a good tune.”

Big Shiny Nine

“We were long overdue to reach down and use some of that secret blues language, which means ‘How do you sing about something with sexual content without saying it?’

“I brought the tune forward, and Frank and Dusty were nervous. They said, ‘Gee, we kind of know what you’re talkin’ about. We’re gonna get busted on this one.’ I said, ‘No, we’re from Texas. It’s about… carrying a 9mm pistol!’ [laughs]

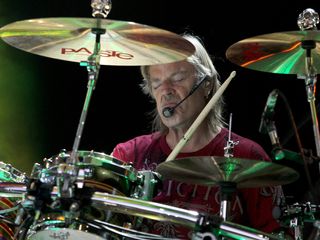

“Frank is drumming great on this record. One thing that changed ZZ Top for the better was in the ‘80s when Eliminator and Afterburner became such runaway successes. Those were the records that made us attempt to play in good time. If you’re a drummer, you’ll know that’s the goal. It’s why Beethoven had a metronome sitting on his piano.”

Have A Little Mercy

“We wanted to do BB King’s Rock Me Baby, but we didn’t want to do the standard throwaway, so we created a new arrangement with some interesting twists.

“The music came first and the lyrics came later. We were sitting on the bus, and it occurred to me that we were no strangers to the use of the phrase ‘Have mercy.’ So I told the guys, ‘Let’s do it.’

“We did a couple of takes – the first one and the second for safety. Practice makes perfect, and we had been playing the musical side of things, Rock Me Baby, for months, so I just said, ‘Hey, let’s play it and we’ll sort out the rest later.’

“It’s got a good sound to it. We were using the Magnatone prototype. It’s a 50-watt, all-tube, hand-wired 2 x 12 combo. A killer-sounding piece, really just awesome.

“At some point, we have to switch the lyrics on this thing live. I’m thinking that by the time we hit New York, you could get either version. We’ll have to find out.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognise his guitar virtuosity, which might be why the song devotes so much space to his shredding": A music professor breaks down the theory behind Prince's When Doves Cry

“It didn’t even represent what we were doing. Even the guitar solo has no business being in that song”: Gwen Stefani on the No Doubt song that “changed everything” after it became their biggest hit

"It may have bothered him that people didn’t recognise his guitar virtuosity, which might be why the song devotes so much space to his shredding": A music professor breaks down the theory behind Prince's When Doves Cry

“It didn’t even represent what we were doing. Even the guitar solo has no business being in that song”: Gwen Stefani on the No Doubt song that “changed everything” after it became their biggest hit

Most Popular