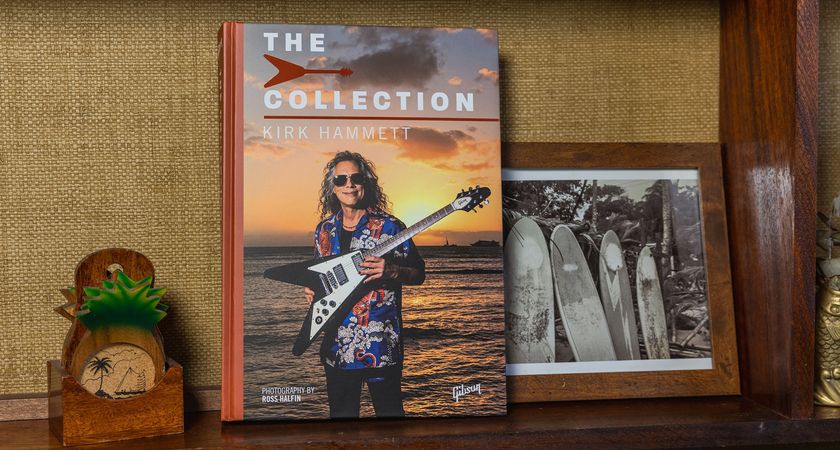

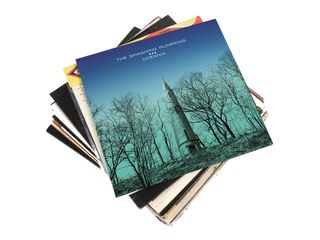

Interview: Billy Corgan talks The Smashing Pumpkins' Oceania track-by-track

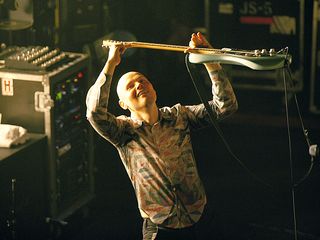

Over the years, Billy Corgan has gotten used to taking his lumps. Coming off the critical and commercial high of 1995's Mellon Collie And The Infinite Sadness, he released a string of albums, Pumpkins and otherwise, that were met with varying degrees of hostile scrutiny.

Corgan lists them all in order: "Adore, Machina, [Zwan’s] Mary Star Of The Sea, The Future Embrace and Zeitgeist. That’s five albums since Mellon Collie, and each time I had to hear, ‘It’s not what I want. It’s too this, it’s not enough that, blah blah blah…’

“Also, for the past 15 years, I’ve sat back and seen a lot of people I don’t respect get incredible reviews for making the same album every fucking time. It’s a bit daunting when you’re trying to be a progressive musical artist and you don’t even get points for trying. So I guess if I keep making Today and Bullet With Butterfly Wings then I’d be good, right? That’s the message I’ve gotten.”

Refusing to give in and deliver an image - and product - that a lesser artist might want his public to believe in or accept, Corgan has chosen the harder route: he's surrendered to his heart's most urgent commands and crafted Oceania, an album concerning his feelings about life. And in doing so, he's created a record of matchless beauty that stands among his best work.

Recording during the midst of the adventurous, expansive Teargarden By Kaleidyscope project, Oceania is the first full album - an album-within-an-album, as it's sill part of the Teargarden narrative - to feature Pumpkins members Jeff Schroeder (guitar), Nicole Fiorentino (bass) and Mike Byrne (drums), all of whom establish themselves as vital players.

Regarding the process of working with his new lineup, Corgan says, "At the risk of sounding ironic, it’s a more sober atmosphere, and probably a bit more studious. Because I don’t have to deal with some of the sub-politics that I had to in the past, I can be very clear: ‘This is what I need. This is what I’m looking for.’ We work very effectively like that because everything is right up front. You’re not dealing with some sort of weird, bruised egos.”

Corgan has heard the early, enthusiastic buzz about Oceania, and after being slammed for so long, he admits that the glowing notices are “a bit weird. It’s like being told over and over again that you’re ugly. The first person who says, ‘You’re beautiful,’ it makes you think, Uhhh, are you sure your glasses are all right? So it’s strange. I’m just not geared to thinking that way anymore."

But he's in a good place, especially as far as the new group (if you can still call them that) is concerned. Oceania isn't even out yet (it streets 19 June), and already, Corgan says, he and the band are talking about making another. "A double," he says with a laugh. "See, there's the insanity, right?"

On the following pages, Billy Corgan walks us through the grand and glorious Oceania track-by-track.

Quasar

“It was one of those riffs that we had laying around for a while. Actually, I think it went back to when I started working with Mike Byrne in 2009. The original riff was called ‘Nero Riff-O.’ So it sat around for a long time, and I was finally able to turn it into a song.

“It's a little bit of what I used to do, even in terms of process. The way I wrote when I first got into rock was, I’d write these crazy riffs and time signatures, and then I’d sit there and think, OK, what the hell am I going to sing over this? It was a way of working backwards.

“With a song like this, I know we were using a combination of a Marshall Super Tremolo amp with four rhythm guitars, and the other guitars went through a Reeves Custom Jimmy head, which is the re-creation of Jimmy Page’s Led Zeppelin I amp. It’s incredible.”

Panopticon

“It’s similar to Quasar in that we had the opening riff and didn’t know what to do with it. It sat for a while, but everybody felt strongly about it. It had a, dare I say, ‘modern-feeling’ to it, but still in the style of guitar that I like to play.

“Ultimately, I just sat down and wrote the song on the piano. Sometimes, when you’ve got a riffy song, it helps to just play the chords with no rhythm, and then you hear the ‘song’ in it. It’s those very Paul McCartney/Wings-type chords – Broadway-type chords.

“What I’m most proud of from a songwriting standpoint is how it goes from D major to A minor. It goes from a very ‘majorly’ feel into something sorrowful, almost a Spanish feel. I don’t know how the heck I did that, but it’s one of my favorite things in the song, how you can keep the key but change the emotion.”

The Celestials

“It’s funny: I was talking to Bjorn [Thorsrud], the co-producer, after I had my favorite part of the song – it was all arranged – and I asked him, ‘What did you think of that? I really like it.’ He just said, ‘Ah, it’s a bit of a downer, isn’t it?’

“I have all of these vintage keyboards that we just crank out when I need something, so I don’t really know what’s on here. It’s some super, highly obscure ‘70s keyboard.

“The arrangement is kind of like classic MTV, circa 1994. You start with the acoustic and then the band kicks in grunge. I was kind of laughing about it at the time.”

Violet Rays

“This is interesting because it was written as a straight acoustic song. I had it all mapped out – words, everything – on acoustic, and then I got into the studio and it was like, ‘This is a really good song – now what?’

“Actually, now that I think about it, before I even had the song, I had the ascending figure. So for a couple months, I would play the demo of that figure and say, ‘OK, I’ve got to write a song around it.’ I broke it down to the chords, no rhythm, and then wrote the song melodically around that and reverse-engineered it back into the riffs.

“This song, in particular, really shows what the band is bringing to the table. There’s a certain vibe and ambience that’s very much them. There’s a lot of parts to it. We’re rehearsing it right now for the tour, and we’re like, ‘What the fuck is going on?’ [laughs]

“The arpeggios are actually a Moog 55 keyboard. That’s the thing about the old Moogs – they’re very musical. If you listen to the Moog 55 on Abbey Road, it almost sounds like classical music.”

My Love Is Winter

“Originally, it was written as a ballad. We actually played it live as a ballad, and it went over great. People loved the song. When they found out we were recording it, they wrote on my Twitter, ‘Don’t fuck it up!’

“But we just felt there wasn’t as much potential in it as a ballad. It had what we call a ‘shoegazer’ vibe, like the band Ride or something.

“Again, this is a song where the uniqueness of the band’s contributions stand out. Jeff plays some really cool, floaty, almost Echo & The Bunnymen-type lines. Nicole is super-active melodically, playing a nice counterpoint to the vocal. And Mike is a fantastic groove drummer.

“There’s a few nods to Yes in the song. [laughs] Anytime you can give a nod to Yes, that’s good enough for me. What a great band! I’m a huge fan. I think they’ve done incredible work.

“My guitar solo is triple-tracked. On stuff like Pinwheels, there’s lead guitar work by Jeff and he’s double-tracked. To me, if you’re going to double or triple-track a guitar, it’s got to be the same person, unless you’re Judas Priest or Iron Maiden. There’s a certain sound they get because they’ve played together, so their doubling works, even if it’s not a perfect double. But there’s an effect you get if it’s the same person – it gets really loud in the track.”

One Diamond, One Heart

“We tried it as an acoustic song, but it sounded like a nice but unremarkable kind of K-Rock ballad. So we started throwing stuff at the wall to find some energy.

“I really liked the track, but I think at one point it was very keyboard-heavy, and it was only going so far in my mind, so I went to Nicole and said, ‘You’ve really got to pull a rabbit out of the hat. You’ve got to make something happen.’ She sat down, and in two hours' time she wrote the bass part. That, to me, was the turning point.

“In terms of unexplored territory for me as a writer, someone like Nicole can bring this different melodicism and approach where you can play something simple, and you don’t have to rely on strings or guitars to get it past. You’ve got another voiced instrument. If you played her lines on a piano, they’d be very beautiful, but there’s something about a stringed instrument – an expressiveness.

“That’s why it’s such a good band record, because it’s not just me creating the majority of the picture. It’s a wider set of influences, a wider palette.”

Pinwheels

“I think I got in this mood, maybe it was from reading the Keith Richards book, but I wanted to play in the open G tuning, which is a country kind of tuning. I wrote the core of the song, and then we messed around with the basic parts for a long time.

“Everybody agreed that it was a really good song, but no one liked its direction. That’s another thing I compliment my bandmates on. They had no problem in saying, ‘Love the song, but we need a better version.’ That’s music to my ears. I’m all for that. I need that kind of feedback.

“We jerked around for a long time. At one point, I think I was playing a B3, and it had an early Led Zeppelin vibe like Thank You. But it just wasn’t getting the job done; we didn’t feel strongly about it. It wasn’t until we produced it, almost like a prog track, that it started to take on a life of its own.

“That’s all Jeff’s guitar stuff at the end. What I love about Jeff as a musician is, he’s always learning, he’s always pushing himself. Technically, he’s far superior to me, but where I’ve been able to help him is, not to just say, ‘Study this guy,’ but to explain to him why I think a particular guitarist would help him. And he came back and said, ‘I’m really understanding why you asked me to listen to this guy.’

“Every guitar player struggles with this. ‘Oh, I can play super-fast’ – and I’m as guilty as anybody. But then we all sing along to the Brian May solo. There’s something about melodicism that Jeff is starting to tap into in his own playing, and it’s been a huge contribution. He plays completely different from me, but that’s what I want. He’s really coming into his own. He’s finding his voice.”

Oceania

“For the longest time, we just had the opening figure and some other parts. The way that it’s broken into three sections wasn’t the original intention. It was meant to be a long song, but we were like, ‘This is going nowhere.’ So the arrangement that is there came together the day we recorded it. I just winged it. We felt strongly about it, and that was it.

“If you take those changes, Section Two and Section Three, and played them over the opening beat, they would feel kind of unremarkable. It was something about placing them in a different context a la Yes, with a little nod at the end to Vangelis [laughs], and it just seemed to work. We didn’t sit around and intellectualize it. There it is – it works.

“What’s really interesting is, when we went to play the song live – you think, OK, it’s this one thing that’s on the record – it became a total show piece.

“The soloing... I think that’s a Strat. I know I hooked up two phaser pedals back-to-back, and they were exploding on each other. As long as I kept playing, it worked, but if I stopped it made this horrible death noise.”

Pale Horse

“Pretty much from beginning, this was one of those ones where you have a good riff, and you say, ‘I’m going to write a song around it.’ The original demo, which was very stiff and choppy [sings] – ‘Da-da-da-da-dum’ – with a drum machine or something, but you actually say, ‘I really like that feeling.’ So then it becomes ‘Can we convert that to the band?’ Right away, the band said it was a really great song.

“A lot of times when you have that kind of riff, you don’t want to get too tricky. It creates a hypnotic effect. You don’t want to change keys too much, so I leaned back on some of those artists who used space well. In old Pumpkins ideology, if you started with that riff, the song would get bigger and louder. In this ideology, it actually gets smaller, and that’s how you get the dynamic back up.”

The Chimera

“We were recording drums for something else, and there was a problem with the snare drum. I had 10 minutes where I was just standing there with a guitar around my neck, so I started playing a riff. Mike just went, ‘Oh, man, I love that riff!’ I was like, ‘Really?’ So to be a show-off, I quickly arranged it into a song. Mike was all for it, and within a week we were recording it.

“A few people have asked me what it’s like having a 20-something in the band. Does it have an influence? In this case, I would say absolutely, because it’s a song I might not have done without Mike's encouragement.

“That being said, once you go into that riffy, exploding tower, then it’s all into the bag of tricks to make it work, because without that it sounds pretty basic. You know, we’re laughing while we learn these songs because we’ve got so many fucking overdubs! [laughs] And everything’s harmonized. It’s not enough to just have the one, you’ve gotta have four.”

Glissandra

“Honestly, this is another song that happened when we were sitting around in the studio, waiting for something to get fixed. I started playing the riff, and we were all thinking, Oh, that’s good. I went home and wrote the melody and some of the lyrical content.

“The next day, I played it for Nicole on acoustic guitar, and she almost started crying. She said, ‘God, that’s so beautiful.’ And I was like, ‘OK – that works for me!’ [laughs] Heartache never gets old.

“Within a few days we were tracking it. Somewhere along the way, I bought one of those old guitar synths – I think it’s the first Roland one. It’s the one where you don’t need the special pickup; you just plug straight in. It tracks semi-poorly, but that’s part of the sound.

“Also, I’m using this Boss pedal where it’s kind of like a whammy bar. So that’s me going ‘errr-weeeer-weeeeer’ with the pedal. It’s one of my favorite sounds on the record. The whole band loves shoegazer music, particularly from the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, the UK stuff. Ride, Slow Dive, Swervedriver – we’ve toured with some of those bands. So it’s trying to find a combination of an underneath club feel and shoegazer on top.”

Inkless

“Of all the songs, I really debated not putting this on the record because it’s so the old Smashing Pumpkins mentality. But I just love the song. I love it! And in a weird way, being conscious about the journey of the album, there’s something kind of nice about going through that long journey and having it resolve – in a way, with the last rock song on the album – with this Siamese Dream-ish feel.

“That being said, there’s other stuff in there that doesn’t sound like any Pumpkins stuff. But that first feel, that ‘neeeeeeehhh!’ – all that – I went back and forth on it. I have to say, I really like it. It’s one of those guilty pleasures. I definitely see myself crankin’ it up in the car.

“The solo… I remember we were mapping the guitars out, and I decided to just leave all this space for some reason. People would say, ‘What’s that for?’ and I’d be like, ‘Oh, I’m going to put the solo in there.’ It’s pretty unusual, the drop. You hear it on Queen records because of the nature in the way they worked, but it’s pretty unusual in most modern music to hear no rhythm guitar at all. But I love it because you can really hear the texture of the sound and take the journey of the crazy bends.”

Wildflower

“It dates back to the original Teargarden sessions, a demo I did with [The Electric Prunes’] Mark Tulin. I think Mike was around, too – he had just started. Originally, it was just like a country song – very twangy, like early ‘70s Byrds.

“After Mark died in the early part of last year, I found myself going back through the tapes of all the stuff we did, kind of mining for forgotten riffs and also taking this weird walk down memory lane of how he’d impacted my life. I came across the song, and I thought, ‘I’ve just got to do something.’ I specifically remember Mark, when I came up with the idea for the song, he was like, ‘I love these chords! It’s so cool, the way you put the chords together.’ He would always say, ‘How do you come up with this shit?’ [laughs]

“I’m a real fan of when chord revolutions don’t resolve. Cherub Rock’s like that, too. You never feel that sense of ‘dahhhh!’ until the end of the song. It creates an anticipatory effect.

“To write an entire song around one chord sequence, essentially – there’s one minor bridge in there – nine-tenths of the song is that same sequence over and over again. It’s kind of got a hymn aspect to it. I really like it in that sense because it reminds me of Mark and how he’s affected my journey. It’s a kind of a sad ending to the record – I didn’t intend that, but it’s just the way it worked out.

“We just played it in rehearsal the other day for the first time, and it was one of those things where you hold your breath. We’re going to do the whole album live in sequence, and you think, OK, is this thing going to work? Is this really going to close? And the first time... it worked. It felt good.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

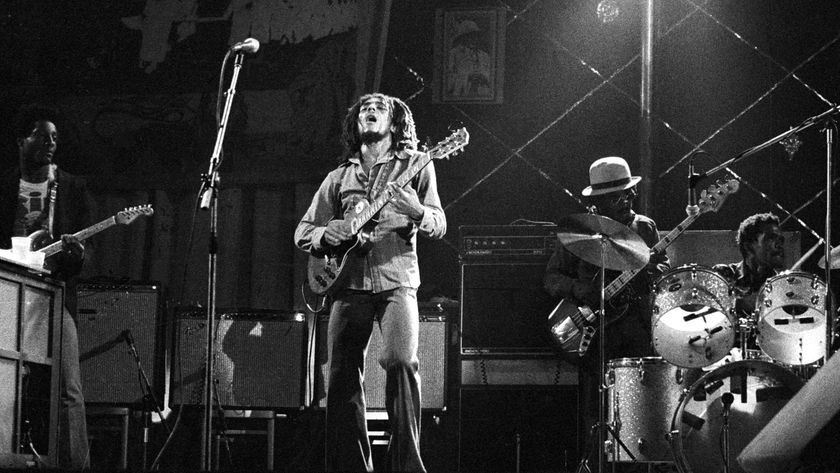

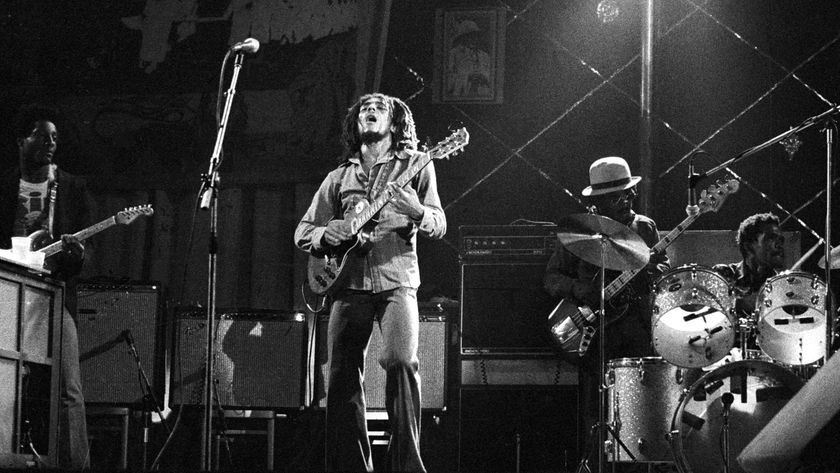

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues