Inside the workshop: Taylor's Andy Powers

Thoughts and philosophy from the luthier supreme

Introduction

Taylor’s master luthier surfs for inspiration, plays like a pro and makes guitars by hand in California. Where do we sign for that lifestyle, we ask Andy, as we tour his immaculate workshop - and find out why even the most cutting-edge Taylor guitars start life here, amid traditional hand tools and wood shavings.

Get Taylor’s master luthier Andy Powers going on the subject of old records and you’d better be prepared for a long conversation. Like a lot of guitarists, he grew up devouring great guitar playing on vinyl - and genre didn’t matter nearly so much as what the player was putting into it.

I can’t really separate playing music and making instruments - and I can’t separate listening from that process, either

“I started off on piano and then I discovered the guitar and got really into The Ventures and Hank Marvin and The Shadows,” he recalls. “Then I got really into Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton, and I fell in with some older musicians who turned me on to Django Reinhardt. And then I got really into Charlie Christian and Wes Montgomery, as well as the fusion movement. But at the same time my dad is a big country and western fan, so I’m listening to Pat Metheny one hour and then the next I’m listening to Lester Flatt playing with Bill Monroe or Earl Scruggs. And I couldn’t separate those interests because I love those different styles.”

Growing up with those influences in a house full of musicians, Andy really knows his way around the fretboard (we’re not kidding, check out Maaren’s Nocturne on YouTube some time). It seems a bit unsporting to have acquired both craftsmanship and session-grade chops, but there it is - and, in fact, he says a good ear is as necessary for making guitars as it is for music.

“I can’t really separate playing music and making instruments - and I can’t separate listening from that process, either,” Andy explains.

“Because what the tools say to you as you work with them, or what a material will tell you… You can hear the way it changes as you work on it. So, parts of the guitar-building process I’ll only do in the morning when my ears are fresh.

“For example, if I’m finalising the voicing on a top for a new design, say, I don’t trust myself at the end of the day. Not because I tune parts for specific notes or anything like that, but what I do is listen to the way that parts change as they get worked on. That’s really what tap-tuning is: you’re not tuning for specific resonances or pitches usually; it’s a very direct measurement of stiffness and weight in terms of sound velocity, and some of the hard-to-quantify parameters of building an instrument.”

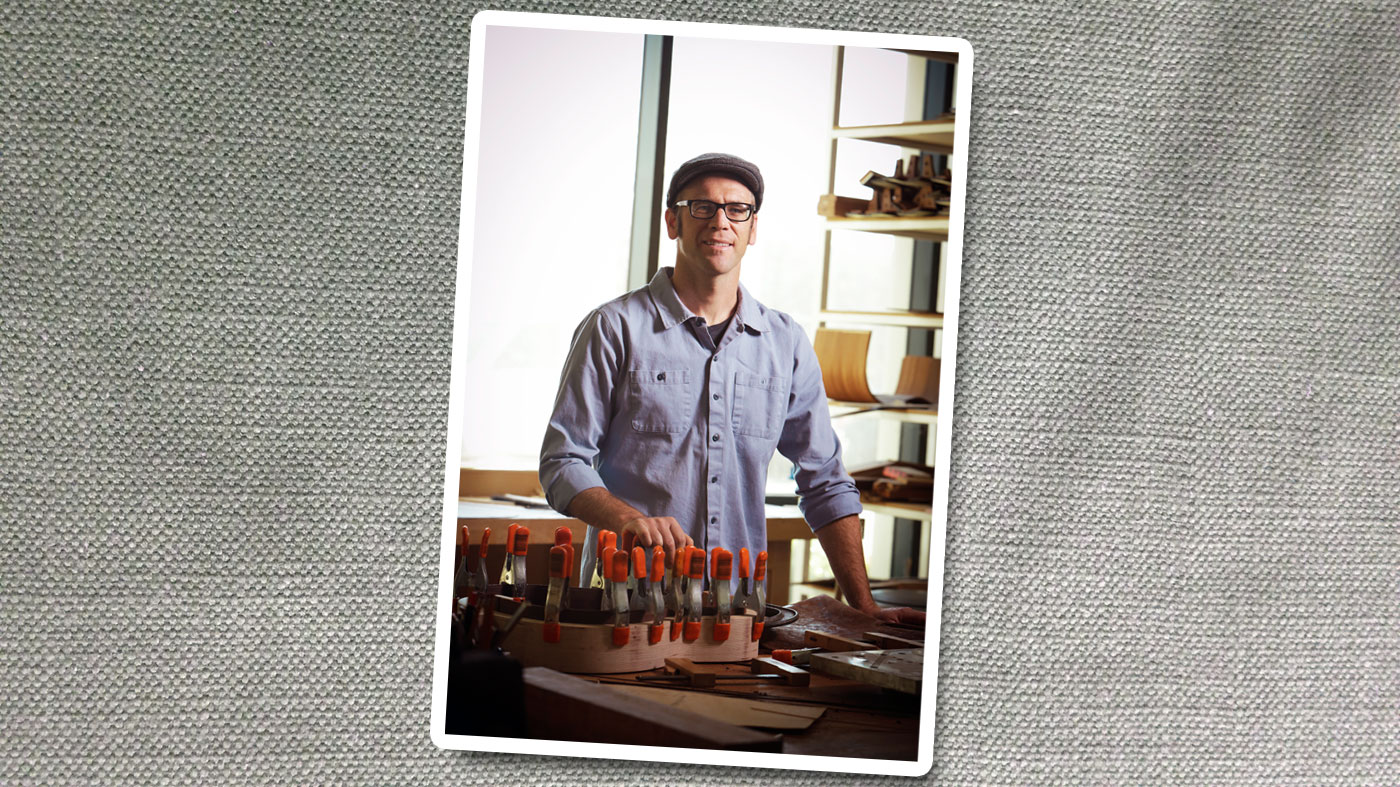

Andy’s tone laboratory, located at Taylor’s headquarters in San Diego, California, is a small old-fashioned workshop within one of the most advanced guitar-making factories anywhere.

It’s worked out that way, Andy says, because the Taylor formula is to craft new types of guitar by hand - listening, experimenting and finessing until everything sounds as it should - then working out how to make the same guitar on the production line, without losing the tonal character of the original, and in such a way as to permit serious numbers to be constructed and put in the hands of all kinds of players.

“I’m a fan of the traditional hand tools, partially because that’s what I grew up with and I developed a fascination with how they worked and how ultimately flexible they are,” Andy says of the enduring usefulness of traditional tech, even when designing new guitars. “I’m particularly fond of the tools of Ashley Iles in Sheffield,” he adds. “A lot of modern woodworkers enjoy using the Japanese traditional chisels, with the hollow-ground backs and whatnot, but I learned with a very old set of Marples chisels that I like very much.

“These chisels that Ashley Iles is building,” he continues, “they’re traditional thin ground bevel-edged, dovetailing joiners chisels. They’re the best ones for guitar-making that I’ve found. Wonderful metal and just a delight to hold.”

Space to think

The meditative side of working with hand tools also gives him space in which to think, and that’s important, he says. Andy says a lot of ideas spring out of pondering long-standing problems in guitar design as he’s working. Taylor’s recent small-body 12-string acoustics, such as the 562CE-TF (see review, issue 404), are a case in point.

“I’d been thinking about the 12-fret 12-string for several years. Because, as I’ve built various 12-string guitars, I’ve realised that from a physical perspective there’s a few things against you.

Logical re-evaluation of old guitar-making techniques is what keeps things interesting for Andy

“First of all, you have almost twice as much string tension as a normal guitar. That means that there’s a massive amount of tension on the top, preventing it from vibrating. Secondly, each string is comparatively smaller than on a regular guitar so there’s very little inertia in each individual string. So now, to recap, I’ve got a top that doesn’t want to move, because it’s under a lot of string tension, and I also have smaller strings than normal trying to make it move. That’s two strikes.

“For me, the third strike would be that a large-body 12-string guitar needs relatively heavy bracing to make sure that it maintains structural integrity - just like a large room needs a lot of structural support.

“So, I thought, ‘What if I build this around a smaller guitar?’ Then things start going a different direction: I still have that string tension, but a small body is inherently very strong. The imaginary ‘walls’ - the sides of the guitar - are closer together, therefore the top isn’t going to deflect as much and I don’t have to worry about the structural integrity of the guitar so much. I can be more concerned with building a wonderful voice into the top bracing instead.

“Also, the natural air resonance inside the smaller body emphasises the higher part of the guitar’s frequency range, and that’s the part of a 12-string guitar I really want to hear: the chiming factor. So that’s going for me, too.

“Now, looking at it from the smallbody perspective… of course it’s gonna work. Then it’s just a matter of making the bits and pieces that go together for that guitar and voicing the top and the back and everything to complement each other.”

This kind of logical re-evaluation of old guitar-making techniques is what keeps things interesting for Andy and, while traditional acoustic guitars such as dreadnoughts seem evergreen and unchanging, he says that there’s no reason that they shouldn’t evolve a lot more as time goes by, through thoughtful development.

“The instrument itself is still a relatively young instrument,” Andy says. “I think there’s a lot of room for improvement. I want to hear more volume, more sustain, more richness. More expressiveness. Ultimately, I want to enrich players’ lives. I want them to enjoy the artful experience and contribute to their enjoyment.”

Join us in the following pages for a walkround of Andy’s custom shop, and for some more perspectives on what makes great acoustic tone tick…

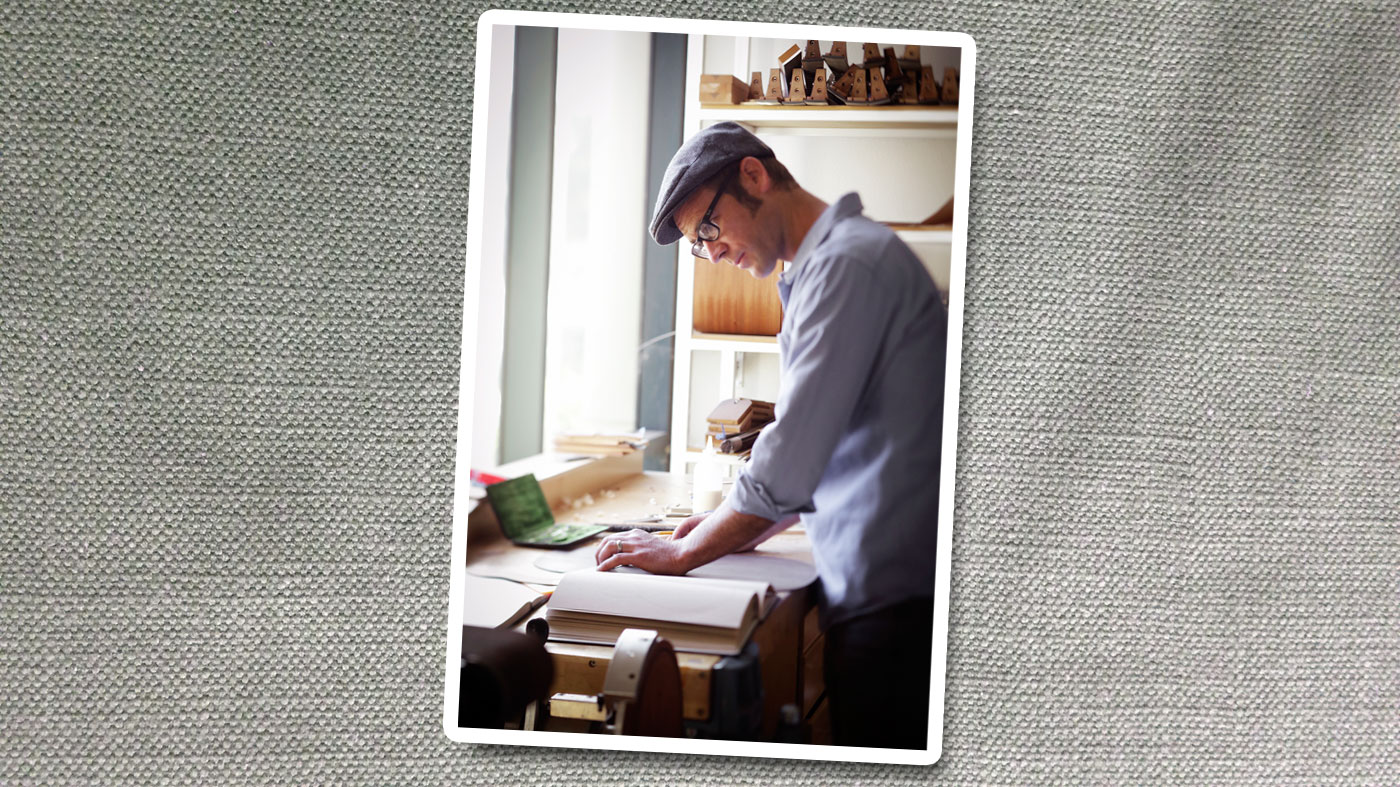

Smooth sides

“In this picture, I’m smoothing out the insides of a set of sides. It’s a pretty traditional way to do it: I’ve got a handscraper. It’s a very traditional type of tool that kind of predates sandpaper, if you will. But they work wonderfully well.

I bent those sides on a hot pipe, in the way you would have 100 years ago

“Now, in this case, the reason I’m doing it this way is that’s a guitar that I’m building that we don’t yet produce. It’s a different shape entirely: that’s why I’ve built a more traditional - in this case, plywood - mould. It’s an ‘outside’ mould where I’ve stacked up a bunch of pieces of plywood and so I’ve sawn it, sanded it and carefully worked the shape for this new guitar.

“We don’t have any tooling yet, so I bent those sides on a hot pipe, in the way you would have 100 years ago, and now I’m smoothing out the insides getting them ready to join the two halves together and put linings and things in there.”

Dishing the back

“That looks like a back in that picture - I have a traditional dial caliper because the guitar that I was building in this photo is a classical guitar. And I’m using that scraper and even some handplanes to alter the thickness of that back.

“Often the back or the top of an instrument won’t be a uniform thickness all the way across. Deliberately so. Because you can control, ever so slightly, the flexibility and how that works with the bracing you’re about to put on it.

Putting it into a convex shape means we have a little more latitude for it to lose or gain a little moisture

“The dishing on the back of an acoustic guitar serves several purposes: one is the sonic response, because the back is bent into a spherical shape. It’s not like a single radius. What that does is that it places it under slight tension, almost like a musical saw blade, so it imparts a little bit of tension like the diaphragm on a condenser mic. It’s sort of ready to be acted upon.

“If it were completely flat, that would pose structural problems really, because as soon as it loses even a tiny bit of moisture, it goes concave and starts to become weak. It’s going to be more inclined to crack that way. But putting it into a convex shape means we have a little more latitude for it to lose a little moisture or gain a little moisture and still be okay. It makes it a more stable type of plate and it’s not limp.

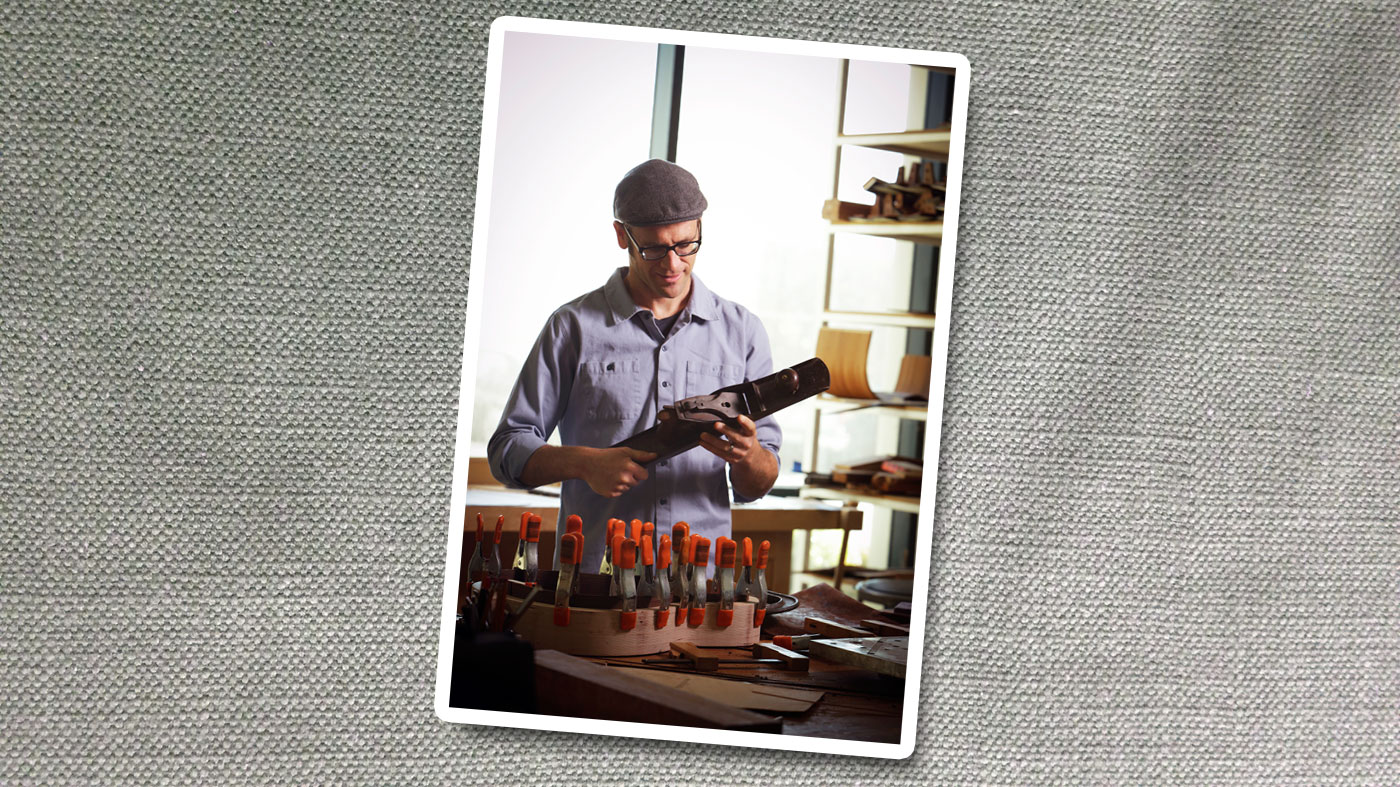

“That’s a big pile of necks behind me. Aside from the way I develop ideas by hand, we’re the most technologically advanced acousticguitar maker that I’m aware of. So when I want to make, say, an alteration to a certain design, even a tiny little internal component, often the best way to do that is through a very scientific, objective approach where you’re building the same thing, exactly the same way, over and over and altering only one detail.

“In this particular case, we were making a small adjustment to the truss rod and I wanted to know what amount of clearance should be machined into the wood that goes around that truss rod. To do that, I’m going to build days and days worth of testnecks, altering only that amount of clearance, by thousandth of an inch increments.

“I figure if I make 10 of the exact same neck every day for, say, two weeks, I’ve got 100 necks. So that allows me to dial it in exactly. Even accounting for the uniqueness in different pieces of wood, I can isolate how the action of the truss rod is affected by this one factor and find out the exact amount of clearance that it needs to have. And so that’s what that pile of necks is.”

Big plane

“I’m a big plane fanatic, partially because I became interested in building them when I was very young. I mean, I was a pretty weird kid!

I use a lot of fingerplanes, handplanes, even down to big, big joining planes

“Pretty nerdy, but I got really into making handplanes because with a good piece of steel for the blade, you can make a handplane that can accommodate all sorts of almost impossible cuts and do it in a very controlled way that gives a lot of precision. So I use a lot of fingerplanes, handplanes, even down to big, big joining planes meant for shooting real straight, accurate glue joints for tops or backs or what have you.

“Traditionally, craftsmen would start with maybe a very rough board and start with very short planes, just to work off small high spots here and there. And then as the board became flatter and flatter, they would switch to a longer plane because it spans and kind of skips over high points and shaves it down a little more accurately.

“By the time they had nearly finished and prepared a surface to become a gluejoint, they’d want it to be the ultimate in flatness and straightness so they would switch to what you would call a long joining plane. The one I have is 22 inches long, so you can span over a large area and make it flat to a few thousandths of an inch. Very, very tight tolerance.”

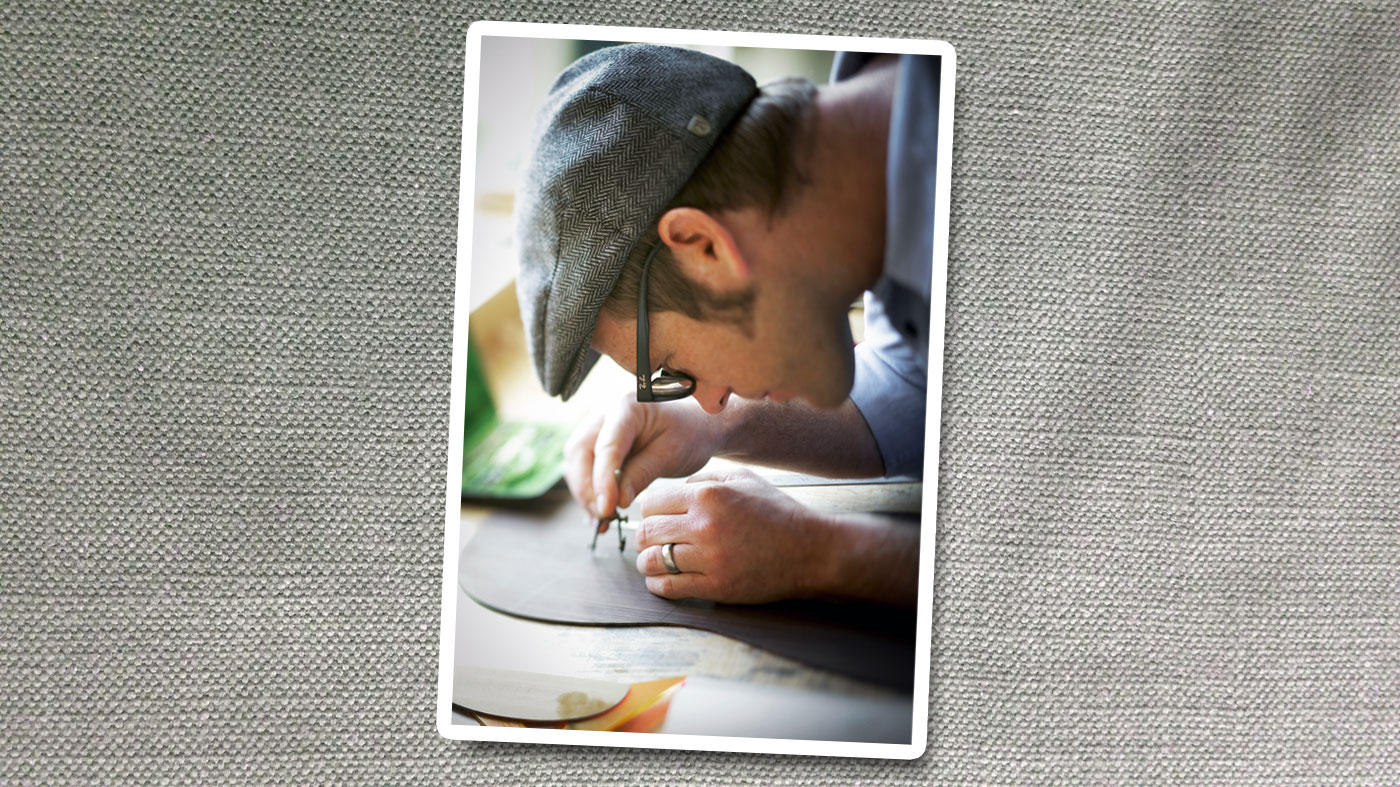

Safe hands

“A lot of times I think a design out through my hands. I think about what I want to build and how I want it to come out - and I learned from an old furniture-maker friend of mine that the best way to realise some of the finer details of a design is to actually get your hands on it and just start working with it and let the wood talk to you that way.

The best way to realise some of the finer details of a design is to actually get your hands on it

“And so I take a lot of notes and make drawings of guitars that I’ve been working on and refining, so I can refer back to them and know that that piece of wood had this characteristic, or that I used these dimensions for a certain set of parts that I made, and I know what the guitar sounds like because I have it here on this next iteration.

“In this case, I’m working on a guitar that’s relatively fresh, so I’m working out where I want the back braces to go on that particular back, looking at some notes from previous guitars that had similar qualities.

“The open green case is a set of cartographer tools that were handed down from my great, great grandfather. And they were beautifully machined, very, very accurate drawing tools. Even in this modern era, I find them indispensable for laying these things out, because when I go to actually physically build the guitar - whether I’ve designed parts in a modern computer-aided drafting programme or not - I still am going to realise it with wood and tools. And so that means I need to lay parts out very precisely.”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.