Ian Hunter talks Bowie, Mott The Hoople's mad guitars and the merits of unprofessionalism

"It's not been a career. It's just been a life"

Introduction

Canonised NME scribe Charles Shaar Murray once stated of Ian Hunter that "I don't know anyone in rock who has as clear an understanding of just how much bullshit the star trip is while simultaneously retaining such an… obsessive love of its glamour."

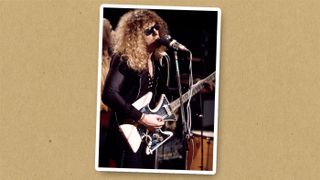

The Mott The Hoople frontman is revered by the likes of Mick Jones, Morrissey and John Squire

That was in 1977. Almost 40 years on, it’s still an accurate description of one of rock’s most self-effacing stars. The Mott The Hoople frontman is revered by the likes of Mick Jones, Morrissey and John Squire, but has confessed to prefer life on the fringe of the mainstream.

Now back with a new solo album (accompanied by his acclaimed Rant band), Fingers Crossed, the inveterate rockstar reflects on the awful instruments of Mott’s early 70s heyday, the impact of his friend, producer and collaborator David Bowie and the “terrible insecurity” that drove his early musical career.

Don't Miss

Malteasers

In Mott The Hoople you had some bizarre custom gear at your disposal – the ‘H’- and maltese-cross-shaped guitars, in particular. What’s the story behind those instruments?

“We were in San Francisco, with the maltese cross. That was in a pawn shop and Mick [Ralphs, Mott guitarist] saw it. The guy was having a row on the phone and was like, ’No, no, I ain’t pulling it down unless you want to buy it.’ We were like, ‘Well, how much is it?’ ‘75 bucks.’ ‘Well, bring it down!’

They looked incredible, but they were unplayable. I don’t think there was even a truss rod!

“It just looked so strange. It was an awful guitar, as was the ‘H’. Both were terrible guitars! But when I turned 70 Joe Elliot [Def Leppard frontman and self-confessed Mott nut] had a facsimile made of the Maltese cross and that one is brilliant. It’s got P90s in it and it sounds like a [Les Paul] Junior, only heavier. That thing is great.”

What was so dire about those original guitars?

“They were awful! I sold the Maltese cross to a bloke in Folkestone and he said he took the plate off and there was a five dollar note in there and the name of the guy who actually built it. I think it was a Thomson and they were an organ firm. I think they must have had some mad director in there for about a year who said, ‘Let’s do these ludicrous things!’

“They looked incredible, but they were unplayable. I don’t think there was even a truss rod! Pete [Overend Watts, Mott bassist] told me I smashed the ‘H’, but I don’t remember. Then, like I said, the other one got sold to the bloke in Folkestone, who tried to sell it me back much later, but I didn’t want it!”

Dandy man

The song Dandy on the new album is your tribute to David Bowie. How did that one come about?

It was drab in England in the early 70s. With David, all of a sudden, you had this technicolour thing

“I was writing a song called Lady, so the song was on its way. I was having a bit of trouble with the lyrics, because the older you get the man/woman love thing, it just doesn’t sound as legit as it does when you’re 25, you know? Then it all happened with David [his passing in January 2016], and it was a tremendous shock. ‘Lady’ became ‘Dandy’ almost immediately and the lyric was there within a couple of days.”

You’ve said the line “And then we took the last bus home” from that song is one of your favourites on the album. Is that referring to a particular memory?

“Well, it was drab in England in the early 70s. You’d had the hippies and you’d had the blues. With David, all of a sudden, you had this technicolour thing. You’d walk down the street, with all the curry houses and pubs, and then you walked into [the gig and] ‘magic land’ for an hour and a half. And then afterwards you’d walk down the street with the curries and the pubs. It was a magic night out and David created that, so really it’s from the point of view of a fan, around ’71/’72 and the Ziggy period.”

Young Dudes

We recently spoke to several of Bowie’s guitarists and the recurring comment was that he was a very receptive collaborator. What was your experience?

Bowie had been working with Visconti and knew a lot about studios, so we learned a lot on the ‘Dudes record

“He was great. He gave his all, he really did. He was 100% there. We’d done [All The Young] Dudes, and we’d done One Of The Boys, which was the B-side of ‘Dudes and then he was like, ‘We should make a record. Have you got any tracks for the album?’

“We were rehearsing somewhere down on Kings Road and he came down and it was like, ‘Ah, these songs are good. You don’t need any more songs from me’ and he worked on our songs. We didn’t really know much about studios, you know, and he’d been working with Visconti and knew a lot about them, so we learned a lot on the ‘Dudes record. He gave his all, he really did. It was a good time…”

The Unprofessional

You’ve spent half your life talking about working with Bowie. Were you not apprehensive that this was going to bring it all up again?

I’m not a professional writer. Stuff just comes and I’ve got to go with it, whether it’s palatable, or corny, or embarrassing

“Do you know, I never thought about it! I just heard the news that he’d passed and it shocked me like it shocked everyone else and the song just went that way. I’m not a professional writer. I’m really not. Stuff just comes and sometimes if I think it’s good, I’ve got to go with it, whether it’s palatable, or corny, or embarrassing or whatever, because I think it’s good.”

So your career with Mott The Hoople and 20-odd solo albums doesn’t make you a professional writer?

“Not at all! It’s just a fluke! I wake up in the morning and there it is. It’s magic. Magicians are bullshit! This is the magic, it really is. Something just pops into your head and there’s the idea. It’s brilliant. Beyond that, who knows? I’ve no idea!

“It’s the most awkward thing to talk about, songwriting. I only ever talked songwriting with one person and that was Roger Taylor [of Queen]. I was down Roger’s house and we were talking and I said, ‘How do you approach writing?’

“He said, ‘I go down to the studio for 11 minutes.’ I couldn’t understand it. I said, ’11 minutes?’ He said, ‘Yes, that’s all I do.’ And he’s right in a way, because anything that’s really going to be special is usually the first thing you do. After that, you’re working on it.”

School daze

You once said that growing up in the West Country as rock ’n’ roll fan “you really felt ill”. What was life like for you then?

My father wasn’t, er, reluctant to explain his point of view to me. He was a copper, you know? It was difficult, growing up

“Well, it didn’t really happen until I was 15. So I spent my first 15 years wandering. I didn’t think like my parents did and my parents didn’t think like I did. My father wasn’t, er, reluctant to explain his point of view to me. He was a copper, you know?

“It was very difficult for me, growing up. I was useless at school. Half-way between my house and the school was the billiard hall, so I’d spend most of my time in the snooker hall and, of course, by the end of the year your tests are crap. They told me that I was good at English Language and English Lit. and Art, so that kept me in school.

“Then all of a sudden I heard Radio Luxembourg and Whole Lotta Shakin Goin On, [by] Jerry Lee Lewis. It was like, ‘What is that?’ And then all of sudden, they all came tumbling in: Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, The Everlys - all of these amazing things were coming out of America. It was fantastic. It was like, ‘This is the reason to live alone!’ It was brilliant.”

Fleeing the factory

What gave you the impetus to pursue music yourself?

“I realised, ‘You’re not going to do anything working in a factory for the rest of your life: you’re going to save a quid a week and it’s not going to work.’ All that you could do if you were crap [at school] was music and football. I was bad at football and I wasn’t that good at music, but I was better at music, so I decided to concentrate on that!

It was out of desperation and terror that we forced our way through… I think it’s a good thing to be insecure

“I was a fan, fan, fan, fan, fan and then I met this guy Freddie ‘Fingers’ Lee. He was a pianist and he was kind of like Jerry Lee and he was working a lot. He’d been with Screaming Lord Sutch and he was playing these clubs in Germany, so all of a sudden I was this bass player with a tiny, tiny ‘in’ and a tiny germ of an idea that maybe I could make this work.”

You once told Nick Kent that all you ever wanted in life was to be a rock ’n’ roll star. Was there a moment where you felt that ambition had crystallised?

“I think the Mott album, which was the fifth album. That was when I thought, ‘Jesus, we’ve got something here - this is first division.’ Before that, no! Terrified! I was terribly insecure, like everyone was. And Stan Tippins [former Mott The Hoople frontman] didn’t help. He kept saying, ‘You’ll be in the factory Monday morning!’

"It was out of desperation and terror that we forced our way through… I think it’s a good thing to be insecure. I know a lot of insecure people and they’re very successful, you know? It’s part of trying to be your best.”

What a Guy

Guy Stevens famously mentored Mott The Hoople and signed you to Island Records. What was the most important thing Guy did for you as a musician?

“He gave me confidence. That was the first thing. If I had anything, it was buried deep in there and he dug it up. He was great. I thought I might have something, but I would never have had the courage to actually put myself forward if he hadn’t had helped. He was absolutely pivotal, not just for me, but the band.

Island Records was full of hugely, naturally talented people and we felt like KISS or something!

“We got on Island Records and we had no right to be on Island Records. Island Records was full of hugely, naturally talented people, like Steve Winwood, Paul Rodgers, all of these people. We felt like KISS or something! [Laughs] We just didn’t feel we were on the right label. We did four albums and nothing much happened, but nowadays we would have been kicked out after the first single! Somehow Guy managed to keep us at that label until we could make a move [to CBS, in 1972].”

How did Guy Stevens go about drawing out that confidence in you, then and build you up?

“He would go one-on-one, like a coach in a soccer team. I mean, he was a total hypocrite, but he was a gorgeous one. He seemed to understand people’s inner-psyche. The story’s often been told, but he would talk in ever-widening circles in the studio - and we had no money, we couldn’t afford to to be in the studio, let alone sit and have a chat! But he would do that for maybe an hour, an hour and a half, before he would let us actually play, so then when you did play, it was like letting the bulls into the ring. Especially with [fourth album] Brain Capers.”

A job for life

A lot of rock bands reportedly got ripped off in Mott's era. Was there anything that you wish you’d avoided in those days?

“Not really, because you have to ‘pay your dues’ - this means you’re going to be ripped off! It’s just a case of how long until your next contract, where you’ll now have a lawyer. I lost quite a bit that way and it’s unfortunate that some of the people who don’t write these songs get most of the money for them.

They’re saying ‘Take it or leave it’ - what do you do? You’re working in a factory and you want to get out

“At the time, though, they weren’t queuing up and I’d have signed anything, to be honest with you. That’s how they get you, especially if there isn’t a queue. If there are two or three labels involved then you’re alright, but if it’s just one person and they’re saying ‘Take it or leave it’ - what do you do? You’re working in a factory and you want to get out. At least it’s a step in the right direction. But you can pay for it handsomely, as a lot of people have.”

Finally, is there a guiding thought or approach that’s served you best during your career?

“I just do what I do and try to be truthful with it. The only time I wrote and was writing like ‘a writer’ was the late 80s and the early 90s and I didn’t like that at all. You have to write honestly. That would be my legacy: ‘he meant well!’ I never planned anything. In the early days, to try and get to the point where you were financially solvent, or a name, or whatever, you worked your ass off, but we were blind as a bat. There was no plan. It’s not been a career. It’s just been a life…”

Ian Hunter & The Rant Band release new album Fingers Crossed on 16 September and tour the UK in November 2016:

04 LEAMINGTON The Assembly

05 GLASGOW Garage

07 GATESHEAD The Sage

08 CARDIFF Tramshed

09 MANCHESTER RNCM

11 LONDON O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire

12 BUCKLEY The Tivoli

13 HOLMFIRTH The Picturedome

Don't Miss

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

“Those arpeggios... That was the sickest thing I ever heard”: Yngwie Malmsteen on why guitarists should take inspiration from players of other instruments if they want to develop their own style

“I used a flange on the main riff and a wah-wah on the solo. I just said, ‘Hit the record button and I’ll let it rip!’”: Kiss legend Ace Frehley on his greatest cult classic song

“Those arpeggios... That was the sickest thing I ever heard”: Yngwie Malmsteen on why guitarists should take inspiration from players of other instruments if they want to develop their own style

“I used a flange on the main riff and a wah-wah on the solo. I just said, ‘Hit the record button and I’ll let it rip!’”: Kiss legend Ace Frehley on his greatest cult classic song