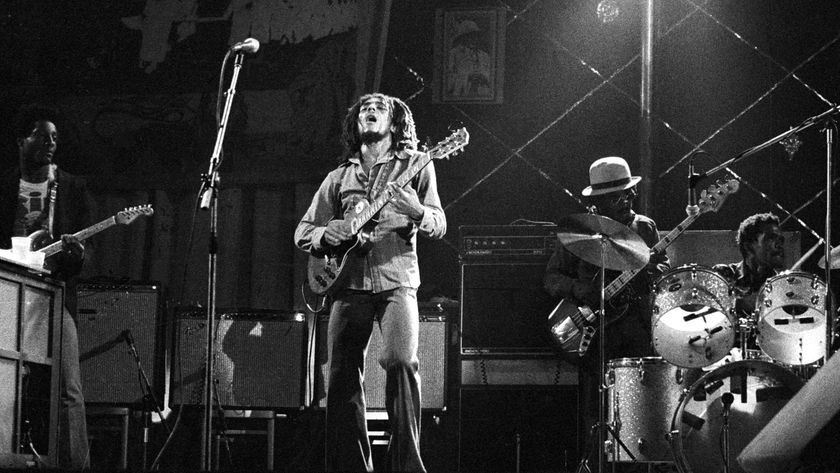

Helmet 2010. Page Hamilton, far right, with (left to right) Kyle Stevens (drums), Dave Case (bass) and Dan Beemer (guitar). Photo credit: Shiloh Strong

Helmet guitarist, singer and songwriter Page Hamilton has seen the highs and lows of the music industry. "What's that song by Judy Collins?" he says. "Both Sides Now? Yeah, I've been through it all, and everything in the middle. The funny thing is, as long as you're in music for the right reasons, and that's to actually make music, it's all OK in the end.

"The danger is when you're looking for something other than that," he stresses. "If you just want to get on TV and get your face in magazines, that's when the problems begin. At that point, I don't know what to tell you."

Oddly enough, back in 1992, Page and co were seen as just that, the group du jour, the hot commodity in the wake of the Nirvana/grunge explosion. "It was so weird," Hamilton says of the major label feeding frenzy that attended Helmet during that era. "We were just this cool little rock band from New York signed to Amphetamine Reptile Records, and suddenly we were taking calls from people who were throwing around ridiculous sums of money. It was unbelievable."

Helmet did sign one of those 'ridiculous' deals, however, and Hamilton is unapologetic for it. "It was the right deal for the right band at the right label at the right time," he says of his agreement with Interscope, an alliance which yielded the gold-selling Meantime (1993) and a handful of other enthusiastically received works. "It's the kind of thing that would never happen now."

After disbanding Helmet in early 1998, Hamilton, who cut his teeth in the noise rock ensemble Band Of Susans and went on to play with David Bowie, formed the band Gandhi. In 2004, he reformed Helmet - the lineup has gone through several permutations since but the current band consists of Page, Kyle Stevens (drums), Dave Case (bass) and Dan Beeman (guitar). "It's a solid group," Hamilton says. "Everybody's focused, and if I say to somebody, 'Hey, go fetch me a beer or move that amp,' they're right there," he says, laughing.

In the following interview with MusicRadar, Page Hamilton discusses the mega-bucks record deal that Helmet signed back in the day. In addition, the sonic shape-shifter talks about the wonders of distortion and how he goes about achieving the ultimate guitar tone on Helmet's brilliant new album, Seeing Eye Dog.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Let's talk about the label feeding frenzy scene back in the early '90s. Helmet signed a deal with Interscope for $1 million.

"That's right."

Looking back, was that a blessing or a curse? Did signing such a huge deal ultimately benefit the band and your career?

"Oh, it was great. No regrets at all, man. It afforded Helmet the opportunity to get our music out to people. Interscope was amazing, a great group of people. I still have tremendous respect for the principles that were at the company and signed us. We were really, really lucky to sign with that label. It's funny, though. A lot of my friends back in New York then were going, 'Don't sign! Don't sign!'" [laughs]

Because they thought you were 'selling out'?

"Selling out to the big bad evil empire, sure. You have to remember that this was all happening right on the heels of Nirvana exploding, and all the labels were looking for that 'next Nirvana.' My attitude was, there's only one Nirvana, and we sound nothing like them. Comparing Nirvana to Helmet is like comparing Mozart to Charlie Parker. They're both cool but completely different. So I thought, If a label is really passionate about what we do, wants to help us get our music out to the people, and aren't going to try to change us -

And will give you $1 million!

"That doesn't hurt. Sure, if all of those ducks are in a row, what's the downside to signing? I didn't want to be playing to a hundred people a night; I wanted to make my music and go for it. If you're not selling your soul musically, and we never did, there's no shame in working with big companies.

"Interscope was a small, streamlined label that had incredible funding and distribution, and we were able to sell 650,000 copies of Meantime. I mean, we didn't have a lot of competition at the label. I think there was, what, Marky Mark & The Funky Bunch and Gerardo, that Rico Suave guy. [laughs] We were given complete attention and respect. I think that's amazing. We never would have been able to bust through the way we did on Am Rep. As cool as that label was, it just couldn't do those kinds of numbers."

Was it a bit of a crazy time, however? To go from Amphetamine Reptile to getting courted by every major label around...

"Oh, it was nuts. I was getting calls at home from all of these label people, A&R guys, presidents - it was wild. But those days are over."

The days of the $1 million deal.

"Oh yeah. The day of the $1 million deal is definitely over. Who would pay that kind of money for a band nowadays? The climate has totally changed. Deals are much different now. They have to be."

That said, what kind of advice would you offer a new band these days?

"I think you can't spend your time dreaming about the fast money and all that stuff that used to exist. I talk to these young guys in bands and they say to me, 'We wanna be rock stars,' and I'm like, 'Really? How boring!' I mean, housewives are rock stars. They've got tattoos and they're on the Internet - it's ridiculous.

"I never wanted to be a rock star. Honest. Even though I signed a big deal back in the day, it was always about getting heard. I always wanted to be a great musician and a songwriter. All the trappings and the money…it's all bullshit. It really is. It might sound trite, but if you want to be a musician, be a musician. If it's what you love, do it. Make it about your music and your identity. Success can still happen, but it happens in smaller ways now. That's just the reality."

Flash forward to 2010 and Helmet is back, although with a new lineup. Chris Traynor played bass on the record, but he's not in the band.

"Yeah, Chris joined us initially, but the lineup that he was involved with when I reformed the band fell apart. Chris and I are great friends, though, and he played great on the new album.

"It took me a while to find the right group of guys who are capable and willing to work their asses off. The kind of music Helmet makes takes total commitment. Chris has a family and is in a different place right now, so he wasn't able to be a part of the new lineup. I'm happy with the guys I have now. The band is killer."

Page Hamilton breaks the Helmet guys up with tales of $1 million deals of yesteryear. Photo credit: Shiloh Strong

One thing that stands out on the new album is your use of distortion, which has long been a hallmark of your sound. What is your philosophy about distortion?

"Distortion is a tonal color, for sure. I look back to my first distortion box, the MXR Plus - I didn't know anything about it, but I loved how cool and crunchy it made my sound. I learned a lot when I played in Band Of Susans and I picked up a lot of tricks. You spend time manipulating sounds and eventually you can become a sonic sculptor.

"Take the piece from the new record called Morphing: I have nine guitars on there, doing different versions of feedback. It sounds beautiful. I always wanted to study orchestration, so I did - I studied at USC. Eventually, I got ideas of how to build and orchestrate distortion and feedback. If you keep an open mind about sound and don't try to limit yourself to the status quo, you can do anything."

Let's talk about your arsenal of guitar effects. Are you old school, new school?

"Both. Everything. It's all useful. On this album, I used a rack that has a Korg SDD-2000 as well as a Lexicon MXP-G2 that I used with David Bowie, so those are modern and not-so-modern digital delays. And I have a fucking truckload of pedals. God, there's so much stuff I've accumulated over the years. I have four main pedalboards with so much weird shit. I used a Moog Moogerfooger MuRF pedal, which I rely heavily on - it's beautiful. Then I have a 1974 Vox wah that's amazing. So many things - I'll try anything to see if I can get music out of it."

What kind of amps are you using?

"My amps are a huge part of my sound. I use Fryette amps, which are incredible. I do have three Marshalls that I use, but they didn't make the record. I like the Fryette amps because they're so well voiced. They're percussive and their range is full of clarity - you can hear every string, even with the distortion. Most amps, when you crank 'em up, it's just a shitstorm. It's big, but it's not musical. Fryette gives you all the massiveness, but you can make out every string and tonal range you're looking for."

The journey for sound, the things you hear in your head…does it get maddening, or is it fun?

"It's not maddening. I like to joke that I've become this divorced loser. You know, I'll date a girl for a few months and then I'll go, 'Hey, I have to go home and program some sounds.' You have to be dedicated, you know what I mean? You have to love the art of sound and be willing to fail. I fail more than I win, but the wins are worth it."

You also have your own line of ESP guitars.

"Yeah, I have the 2006 and the 2009 models. I'm really happy with them. They're the result of years of me playing around and figuring out what works. And I should point out that these guitars are made for rock; jazz players might not take to them. I removed the neck pickup, and there's just a volume knob - no tone knob. The tone is all-out. It's an alder body, maple neck, neck-through design, a Floyd Rose - it's great. But it all starts with the wood. Not every chunk of wood is meant to wind up as a guitar, but wherever ESP gets their wood, they know how to pick the right pieces."

One more question about the new album: You do a fantastic cover of The Beatles' And Your Bird Can Sing. Did you intentionally pick one of the harder guitar songs in The Beatles' catalogue?

[laughs] "No, not at all. I just always loved that song and thought of doing it. It's such an odd track and I always felt like I could do something cool with it. The degree of guitar difficulty didn't come into my mind. I just love the song, the way it progresses.

"The Beatles were amazing. There's another song of their theirs, Dear Prudence…man, there's triads starting at the 15th fret, working through the inversions. Those guys knew their instruments. I don't know if they could sight-read, but they were phenomenal musicians. Anybody who questions the musicality of The Beatles, they're just not paying attention."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues