Who is Harry Nilsson and why is everybody talkin' about him? It's the question millions of music fans are suddenly asking, and one which elicits a couple of complicated answers. There is, of course, his music, which includes smashes such as Without You, Everybody's Talkin' (from the movie Midnight Cowboy), One (the loneliest number you can ever do - yes, he wrote the Three Dog Night hit) and Coconut, a novelty song that has endured through the decades.

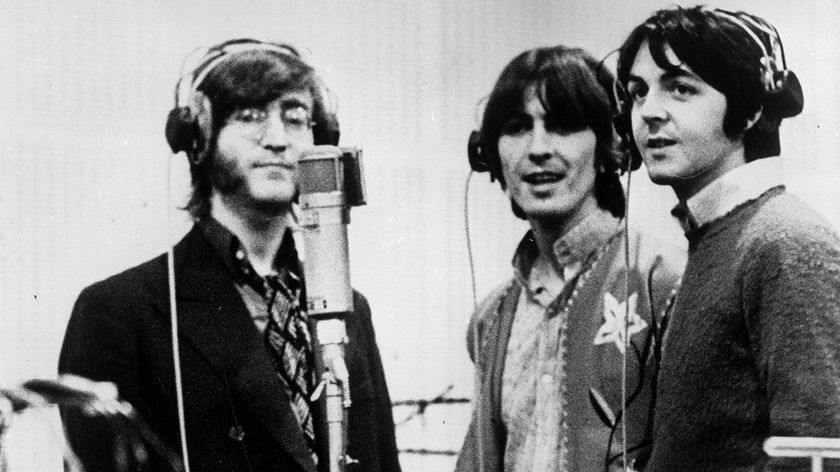

And then there's the other Harry Nilsson, the notorious drinker and carouser, who partied infamously with John Lennon, Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, among others, and who blew his wondrous voice out during the making of the album Pussycats, which Lennon produced.

Yes, Harry's voice was indeed a gift, a fact that is made abundantly clear in John Scheinfeld's (The US vs John Lennon) absorbing new documentary, Who Is Harry Nilsson (And Why Is Everybody Talkin' About Him?). During one of the many fascinating interview segments of this must-see film (available 26 October on DVD), percussionist Ray Cooper talks about how, upon hearing Nilsson's unadorned vocal take through his headphones during a recording session, he almost couldn't play - Harry's voice was so big and stupendous that he froze, stunned that such natural beauty could come from one man.

Harry Nilsson created an incredible and eclectic body of work during the late '60s and early '70s. He wrote hits such as Cuddly Toy for The Monkees, then went on to conceive and write the score for the children's film The Point. He won a Grammy for Everybody's Talkin' (which he didn't write, and would prove to be a source of major irritation).

During this time, he became the guy everybody had to know: one week, he was a cult artist, barely successful enough to leave his graveyard shift bank job; the next week, he was receiving admiring phone calls from The Beatles (John Lennon referred to him at a press conference as his "favorite group"), inviting him to England to hang out while they cut The White Album. And before long, Harry Nilsson was off and running, cranking out daringly original records, culminating in 1971's Nilsson Schmillson, which included Coconut, Jump Into The Fire (the searing rocker that Martin Scorsese used to great effect in Goodfellas) and of course, his breathtaking cover of Badfinger's Without You (another Grammy win).

Tragically, Harry Nilsson died in 1994 of a heart attack, but thanks to Scheinfeld's doc, we now have the story to match the music. MusicRadar sat down with Scheinfeld recently to discuss the making of the film, and why Harry Nilsson's work still burns brightly 16 years after his passing.

What drew you to the subject of Harry Nilsson, and why did you think his story could work for a documentary?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"I was into Harry's music since I worked in as a DJ at my college radio station. I was looking through the record cabinet one day and came across this unusual album, which turned out to be Pandemonium Shadow Show. I looked at the tracklist and saw You Can't Do That, and I thought, Oh no, another horrible Beatles cover! But then I listened to it and was floored. It was Harry's tribute to his favorite band, and he worked multiple Beatles titles into a brand-new creation all his own. I was so impressed that I listened to his first three albums in a row and became an immediate fan. I couldn't believe the variety of material he could come up with, the depth, the sheer musicality. And, of course, there was that voice of his…"

He had one of the truly great voices in modern music.

"Without a doubt. His voice was one of those things you encounter only a few times during your life. What an instrument! Anyway, somewhere around 1999 or 2000, I got to know the lawyer for the Nilsson estate, and he said, 'Hey, how would you like to do a film about Harry?' I told him that I loved the music, but I didn't know a lot about Harry's story.

"So I started doing research, and the more that I read, the more the tale seemed to be compelling, dramatic, tragic, epic - everything you could want. It didn't take long for me to be convinced that Harry's story needed to be told. His career was meteoric in the late '60s and the early '70s, but then it ended, a lot of it by his own doing. And then, of course, he died so young. There's so much beauty in his life, but just as much tragedy."

Was it an easy film to finance and make? I know you had a lot of problems post-production-wise with music clearances.

"Getting it off the ground wasn't so hard. We raised the financing and started making the film before The US vs John Lennon, so we were able to piggyback some of the interviews in that way. We showed an early cut at some film festivals, and the response was incredible. People loved the film! So, we were set to release it in 2007. That's when the problems started. There's a lot of music cues in the movie, 61 of them, all of them Harry's master recordings. That's a lot for any movie, particularly a documentary. It was a very long and involved process, but in the end, two and-a-half-years later, we were able to get what we wanted. We got the use of the music gratis and were able to work out a distribution deal, and now, here we are - turning everybody on to the magic of Harry Nilsson."

In the film, Tommy Smothers says whenever Harry Nilsson is mentioned, his name elicits either instant reaction and enthusiasm - 'I love Harry Nilsson!' - or a total blank stare.

"Totally. People either know him and love him, or they have no idea. But that didn't deter me from wanting to make the movie."

Well, his music matters so much.

"That's the point! It does matter. I was talking to a school group last year, and I mentioned I was working on a film about Harry Nilsson. You could hear a pin drop in that auditorium - total silence. No one knew who he was. But then I mentioned that he sang Everybody's Talkin' from Midnight Cowboy, and people were like, 'Oh, I love that song!' Then I started rattling off his other songs - that he wrote One, that he sang Without You, that he wrote and sang the Coconut song - and people got really excited. That convinced me I was doing the right thing; that the music did matter, and people were very aware of his contributions. They knew the music but not the man; and to me, Harry Nilsson's story needed to be told."

Watching the film, I was reminded of Neil Young's famous line, 'It's better to burn out than to fade away' - and it's certainly true that Harry did burn out. But do you agree that he had a death wish, an opinion producer Richard Perry posits?

"I'm not sure I wouldn't have used the expression 'death wish,' but he had a very wide self-destructive streak in him. Eric Idle put his finger on it very well when he said that, in his view, Harry didn't feel he deserved all the acclaim. I think his self-esteem was poor his entire life. His father abandoned him, his mother was an alcoholic, he was pretty much left to fend for himself at a young age - I think it really played into his sense of self-worth. You can get all the awards in the world, but deep down, if you've been conditioned to feel you're nothing, it's going to affect you profoundly. Harry was very insecure, and he took that insecurity out on himself in the worst ways."

As we know from history and the film, his drinking got out of control during the early and mid-'70s. But what about that period in the mid- to late '60s, when he wrote One, made some well-received albums, sang on Midnight Cowboy - was he doing a lot of hard drinking then?

"It's hard to say. We get the impression that he was a drinker and certainly a smoker, but the heavy substance abuse didn't really come till he had some success around 1968 or '69. It's one of those strange things about the music businesss in that behavior like that isn't just accepted, it's encouraged - and Harry went right for it.

"A lot of the people I spoke to talked about how bright and energetic he was early on. There was an evolution to him, not only personally but in his music, too, which definitely took on some strange and not entirely commercial edges. I think he found comfort in the carousing. Whether it was John Lennon or Ringo Star or Keith Moon, if there was a good time to be had, Harry was going to go for it - and be the ringleader, in many cases."

It's interesting to consider his low self-esteem was still an issue when he was experiencing success. He loved The Beatles, and suddenly they're calling him, telling him how wonderful he is. He goes from cult status to hanging out with The Beatles and other members of rock royalty, drinking with them, getting crazy…

"I think explanations for this issue - what continued his low self-esteem and fueled his destructive side - are not easy. Harry was a very complex human being. Yes, he reveled in the praise from the press and having his idols say great things about him. He loved hanging out with The Beatles and other celebrities and feeling that he belonged in their club. But deep down, I think he always questioned whether it was real and if he really deserved it.

"What's more fascinating is how his destructive habits escalated as he was achieving his greatest success. Usually, artists artists start sinking when their records stop selling and the phone stops ringing. Harry started the pattern all by himself when he was at his peak, winning Grammys and collecting gold records."

Even though he wrote wonderful songs, some of which were hits for other artists as well as himself, do you think it bothered him that the Grammys he won were for Everybody's Talkin' and Without You - two songs he didn't write?

"I think it annoyed him that he was best known for songs he didn't write, especially when he had such a fine body of his own work. Winning a Grammy is a great thing, but again, because of the kind of person he was, he had a complex response to a set of circumstances.

"You know, we're talking a lot about the dark side of Harry. But in making the film and talking to all of the people who knew him, one thing I came away with was how much everybody loved him. They loved him for who he was, and they loved him in spite of what he was. And what I think that speaks to is that, when you strip away the craziness and some of the negative elements, what we're left with is a very good guy with a big heart. He could be incredibly generous to people, friends and total strangers.

"Van Dyke Parks tells the story in one of the DVD extras about how Harry gave $50,000 to an aging Hollywood actor. We don't know who the guy was, but apparently Harry found out about it - that the guy was down on his luck and was about to lose his house - and he just wrote him a check for $50,000. A guy he didn't even know! This is the kind of man Harry was. He could be his own worst enemy, but to anybody else, if he could help you, he would."

In 1971, Harry made one of the greatest records of the rock era, Nilsson Schmilsson. The diversity on that album is still stunning - everything from novelty tunes to pop classics to blazing rock. Do you feel that he really wanted to make a powerful statement at that point?

"Absolutely. He had been building up to Nilsson Schmilsson, and I think he knew he was ready. The dynamics in the studio between Harry, producer Richard Perry and all the great musicians they had assembled, was incredible. I think everybody knew they were working on something special. It's also my perspective that, on that album, Harry was extremely disciplined. As a writer, a singer, and a musician in the studio - he was 100 percent focused."

Although he was still smoking his head off. At least it appears that was the case from the clips in the film.

"Oh yeah. He was a smoker, for sure. Everybody smoked like that in those days. The Beatles were big smokers in the studio. Go figure. But right after Nilsson Schmilsson, around 1972, as we point out in the film, Harry changed, as did his relationship with Richard Perry. Harry started to fall apart, and you can hear it in the songs. A laziness started creeping in, and Richard couldn't turn things around. Songs would be half finished. Harry would do one take of a vocal and say, 'That's it,' whereas in the past he would do 20 takes to get it right. As a fan, that disappoints me, because we stopped getting the full Harry. The self-destructive tendancies killed his artistry."

I always wondered if, in some weird way, he felt that he peaked with Nilsson Schmilsson, that he'd never top it, so he simply didn't try.

"That's a good one. I don't know. Really, really hard to say. [pauses] I would say, through the haze of alcohol, he thought he was doing good work. But a switch went off on Harry at that point, and with it, so too went a lot of his discipline as an artist.

"It's conjecture, of course, but he might have been frustrated with himself during this period. His rise to prominence was rather quick, and he was embraced by people he idolized and by the public, and then there was his fall from grace and the fact that his records stopped selling and RCA wanted to buy out his contract in '78...I think it really bothered him, and he probably didn't know how to handle it."

We all know the stories of John Lennon's 'lost weekend,' when he and Harry tore it up together in LA. After John came back to New York and spent five years as a homebody, did he sever his ties with Harry?

"I don't think he shut Harry out, but John definitely became something of a recluse. I think one of the conditions that Yoko set down when she reconciled with John was that he cut out the craziness, and part of that craziness was Harry.

"They didn't hang out, but they were in touch. I found letters and Christmas cards that John and Harry sent each other up until the time that John passed away. So they kept in touch, just not in the same way.

"Again, to give some balance here, as Harry's professional life went south, his personal life got better. He married for the third time, and he truly loved and adored his last wife, Una, and they had six children together. Harry loved being a father - even though he was already a father by his first wife and he kind of failed at that relationship - and it brought him so much joy during the last chapter in his life."

Yes, from all accounts, he was a great husband and father the last time around. Did his newfound happiness allow him to curb his drinking?

"There are several answers to that: When I talked to Una and the children, they spoke of the wonderful times they had together, and it was quite genuine. I think he went through periods when he would stop drinking. There was talk of an intervention, although I don't know if that ever happened. At times, when it was important, he would stay off the booze, and his voice would start to come back. But I don't think he ever stopped drinking totally. I do believe that he stopped taking drugs, however, probably around 1980. By that time, though, he had inflicted some real damage to his heart."

Had he lived, do you think he would have returned to music?

"That's an interesting question. I think he was starting to put his toe back in the water. From 1989 to '93, he was back in the studio working with producer Mark Hudson. People refer to this as an album, but it wasn't really. There were some finished tracks, but most of the things they were doing were demos and works-in-progress. Harry was sort of noodling. But it was the first time he was motivated in 10 years to really get back in the studio.

"His health was so bad, though, that I don't think he had the strength to give it his all and make a real album. Had his health not been bad, however, I think he would have started to come out with new records. We would've had fresh music from Harry with him looking at the world in a new way, and it probably would have been fascinating."

In the end, what do you think Harry Nilsson's musical legacy will be?

"We touched on couple of those elements here. At the heart of it, though, I think we have a guy who, in his day, was so different and unique, who created an amazing body of work, who possessed one of the greatest singing voices ever, and whose career then went south…and he died young. And yet, here we are in 2010 talking about him. You still hear his songs on the radio. Even if you don't know his name, you know his music."

Like I said in the beginning, his music really mattered.

"That's the point to this whole thing. Harry Nilsson really did matter. Hopefully, this film will help put the name back on that music…the music people know so well."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

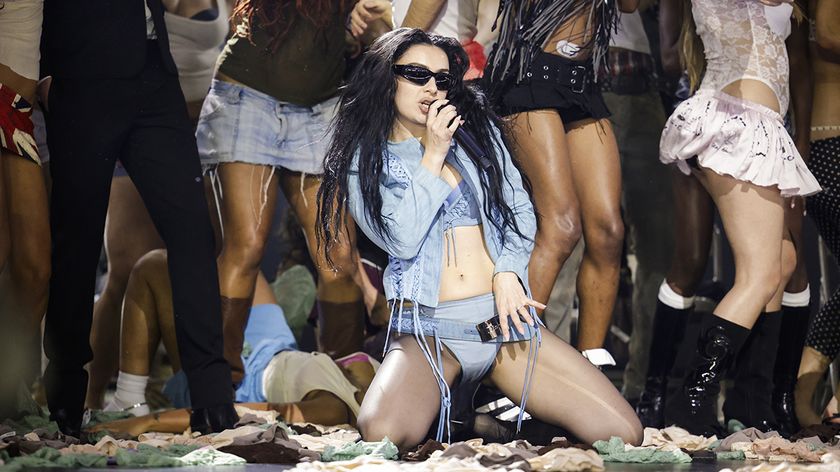

“The verse tricks you into thinking that it’s in a certain key and has this ‘simplistic’ musical language, but then it flips”: Charli XCX’s Brat collaborator Jon Shave on how they created Sympathy Is A Knife

“I’ve seen a million faces and I’ve rocked them all!”: Was Bon Jovi’s 1989 acoustic performance really the inspiration for MTV Unplugged?

![Chris Hayes [left] wears a purple checked shirt and plays his 1957 Stratocaster in the studio; Michael J. Fox tears it up onstage as Marty McFly in the 1985 blockbuster Back To The Future.](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/nWZUSbFAwA6EqQdruLmXXh-840-80.jpg)