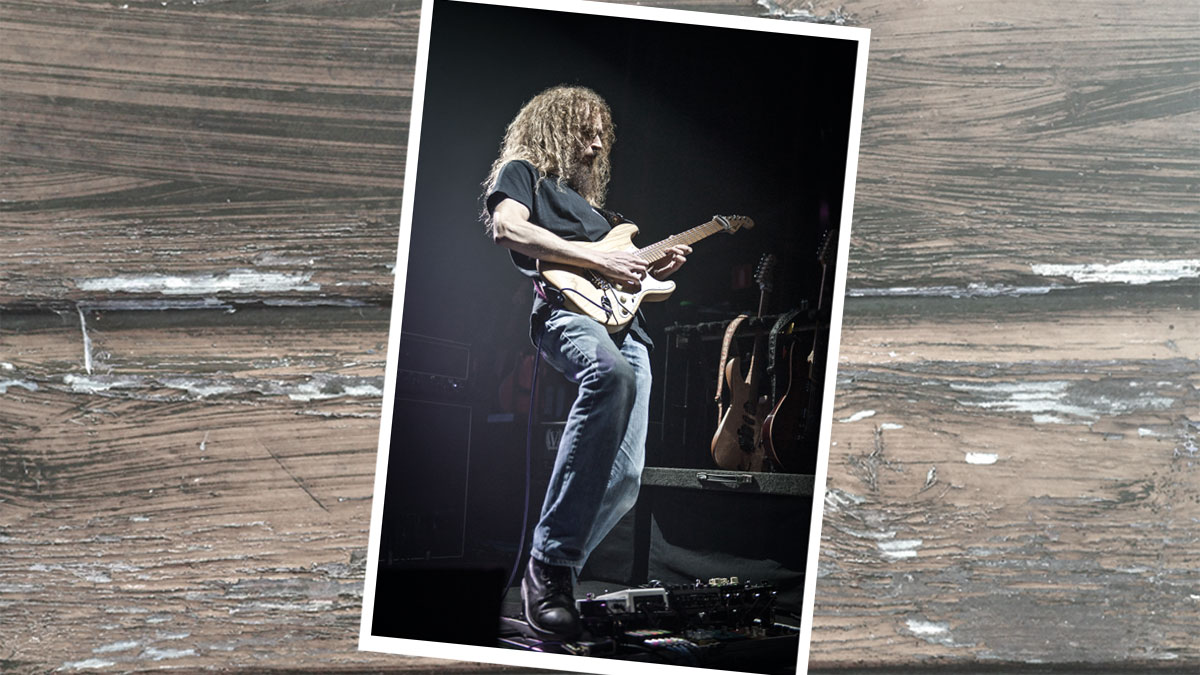

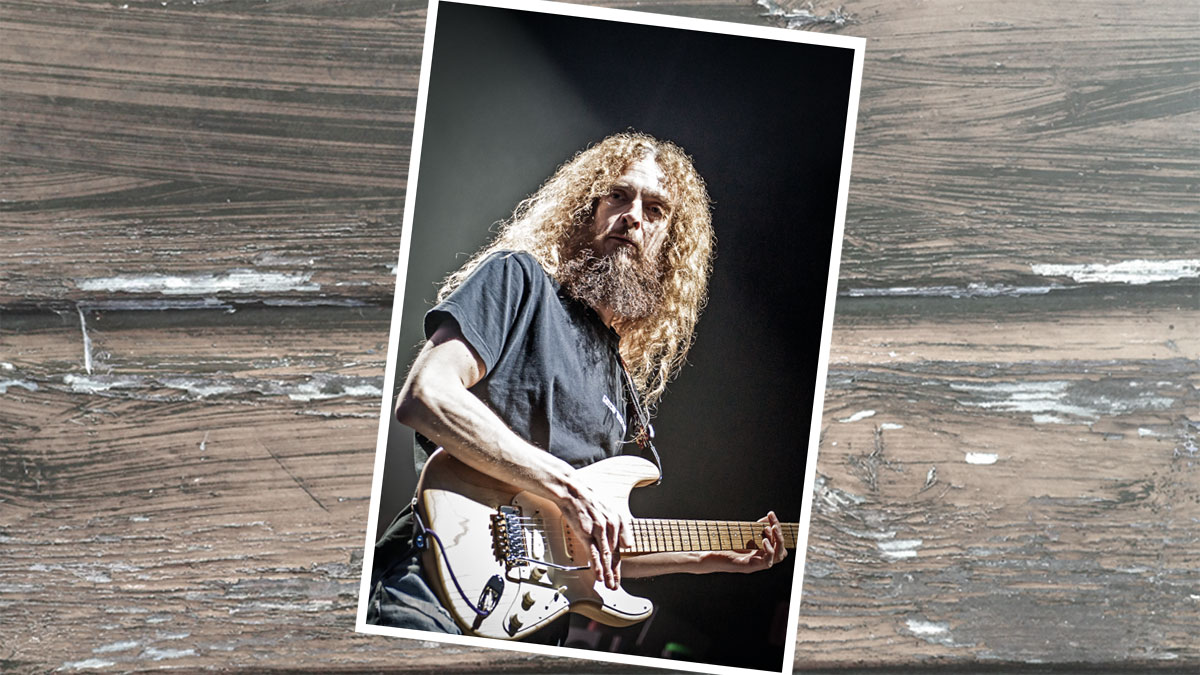

Guthrie Govan on The Aristocrats' new album Tres Caballeros

The gifted guitarist speaks

Introduction

In June this year, Guthrie Govan's super trio The Aristocrats released their highly anticipated third album - and what an album it turned out to be.

Tres Caballeros is a heady mix of musical styles, from all-out, balls to the wall fusion, to country twang in the flick of a pick, the record features the latest fret-melting extravaganza from custom Charvel-wielding guitar guru Guthrie Govan. With all those notes out there on the loose causing havoc among the guitar community, we had to bring him in for questioning.

"This new album marked the first time all three of us went in the studio with absolutely no qualms about adding additional layers"

There’s a very well known syndrome among musicians called ‘that difficult third album’, but it doesn’t seem to have troubled The Aristocrats in the slightest. Far from it, in fact. Tres Caballeros appears to have had an easy birth, Guthrie admitting that he believes it to represent the band far better than anything else to date.

Recorded at LA’s legendary Sunset Sound studios, which has seen the likes of Led Zep and Van Halen pass through its hallowed doors, the new record is every bit as intense and powerful as you’d expect with some guitar solos that boldly go where no fretmeisters have gone before. One of the first things we noticed is that there’s considerably more overdubbing on the new disc...

“The overdub approach was very much an intentional thing,” Guthrie explains. “We were tentatively starting to veer in that direction on the previous album anyhow, particularly on Marco [Minnemann]’s Dance Of The Aristocrats and the middle section of Ohhhh Noooo, but this new album marked the first time all three of us went in the studio with absolutely no qualms about adding additional layers wherever we felt it might benefit the overall impact of the song.

“Given that live playing is such a big element of what we do, we were obviously keen to ensure that the new material would translate well in a gigging environment, so we decided to prepare for our studio sessions with a week-long residency in Alvas, a small and splendid fusion club in San Pedro, California.

“We spent three days there working on, rehearsing and arranging the new material and were then able to road test it for a further four days in front of actual audiences. This turned out to be a really effective approach. At the end of that week I think we were all kicking ourselves for not having adopted it sooner!”

The power of three

All three of you write songs for The Aristocrats - how does the process work?

“Each of us is capable of recording a fairly detailed demo of how we think the tune should sound, and we all write with the whole band in mind, rather than focusing on our own instrument.

"Different guitar tones always tend to make me write and play in a slightly different way"

“Oddly enough, Bryan [Beller] tends to write guitar tunes, whereas I’ll often spend more time working on the bass line. Meanwhile, Marco is undoubtedly the most prolific composer in our operation; he’ll send us enough tune options to fill up a whole album, whereas Bryan and I will tend to focus more on just honing our three tracks.”

The dynamics were obviously very important in Pig’s Day Off. Was it particularly difficult to convey the overall sound you wanted to create?

“Not particularly. Both Marco and Bryan seemed to understand exactly what I was going for when they heard the demo, so the mixing process for that one was more challenging than the actual tracking.

“I should probably add that it’s not easy to make that song work live; its dynamic ups and downs require a fair amount of juggling in the tonal department. But we had the luxury of adding some overdubs in the studio, so I just kept adding splashes of extra guitar here and there until it felt finished.”

Did you have particular tones in mind before you set out to record in the studio?

“Every time I write a batch of tunes for an Aristocrats album, I try to look for a slightly different mindset, in a quest to keep things fresh and generally avoid repeating anything we’ve done before.

“For this album, I deliberately wrote all three of my contributions on a single-coil instrument. I have a Custom Shop Charvel, which basically looks like a Strat and has N3 noiseless pickups, so that became my official Tres Caballeros writing guitar. Different guitar tones always tend to make me write and play in a slightly different way, so I suppose the one preconceived notion I had about tones was that the single-coil character should play a larger role on this album, as indeed it did.

“On the final recordings, Stupid 7 and Jack’s Back were mostly played on a cedar-bodied Tele, which I borrowed from the Fender Custom Shop, and I used a US Deluxe Strat for Pig’s Day Off, The Kentucky Meat Shower and Smuggler’s Corridor.”

Building a solo

Do you think you’ve benefited as a musician and songwriter from playing with Bryan and Marco?

“Oh, absolutely. For a start, it feels liberating to know that there’s really nothing I could write that those guys wouldn’t be able to play. Also, the raw trio format has probably made me think differently about composition.

"I strive for arrangements in which a single guitar part and a single bass part can come together to sound harmonically complete"

“In the past, I’ve certainly tried playing material from my Erotic Cakes solo album with a trio, but I never really felt that the music came across properly in that format because it was originally composed in a much more layered manner.

“One of my big missions when writing for The Aristocrats is to strive for an arrangement in which a single guitar part and a single bass part can come together to sound harmonically complete.

“I like the idea of being able to do the trio thing live and not leave the audience with the nagging feeling that some element is missing, so I think this band has led me to experiment more with various ways in which the guitar and bass parts can interlock harmonically and share the melody.

“Above all, though, we’ve done so much live playing together that hopefully I’ve become a better Aristocrat as I’ve grown more familiar with the overall chemistry of the band.”

Your construction of solos is not particularly formulaic with either The Aristocrats or your solo stuff. How do you usually approach writing solos and how does that approach change when working for other artists?

“I suppose I have a slightly jazz mentality when writing that kind of material. For me, it’s fun to have some thoroughly composed sections in the main body of the song and then contrast those with free-for-all sections where improvisation and interplay are the key factors.

“Consequently, I prefer not to write solos at all. Hard though it is for me to be totally objective about this, I think I play my best stuff when I’m trying to tap into some kind of spontaneous flow rather than adhering to a script.

“Having said that, I’m certainly not opposed to doing multiple takes, if necessary, and in certain studio situations the solo might well start to write itself after a few takes. Maybe the opening phrase will become set in stone, or the overall arc of the solo will gradually become more defined.”

Imposing improv

Live, you prefer to improvise rather than play a written solo...

“I just like the idea of striving to create something unique every night. If every note in the set is predetermined, I sometimes find myself encountering a kind of ceiling in terms of how much the material is able to grow throughout a tour, and I do think that magic is much more likely to happen if you’re willing to allow it to happen.

"That makes someone like Jeff Beck so compelling is you never quite know what he’s going to do next"

“Perhaps this is just a by-product of all the old blues-rock stuff I listened to when I was growing up, but there’s something exciting about taking risks when you solo. For me, that’s part of what makes someone like Jeff Beck so compelling; you never quite know what he’s going to do next and you occasionally get the feeling that perhaps he doesn’t know, either!”

How does it feel to be at the mercy of amateur videographers at gigs? Does the lack of quality control bother you?

“Most of the time, I do my best not to dwell too much on anything that I’m clearly powerless to change but, seeing as you asked, I don’t like the whole filming thing at all. Improvising in front of an audience carries with it a certain element of risk, and I’ve always liked the idea of just trying to create a unique moment.

“I find it can be disruptive to that mindset to think that whatever I’m trying to do, regardless of whether it works or not, could end up on YouTube mere hours later, without any sense of context.

“Feelings like that can definitely inhibit spontaneity - the performance being captured by the iPhone-wielding army in the front row can’t possibly sound the same as the performance that would have occurred if everyone just put their iDevices away and made an effort to engage fully with the music instead.”

A good ear

Do you think you’d be the guitarist you are if the sheer volume of guitar-related learning resources was available at the time when you were learning?

“My technical development would almost certainly have been spared from a lot of dead ends and wheel-reinvention. I’m sure I would also have discovered a lot of new playing approaches much sooner.

"The biggest potential casualty in this age of information overload is surely the development of a good ear"

“Years ago, it took a lot of effort and not a little luck to discover that extreme players like Shawn Lane or Scotty Anderson even existed. Now, inspiration like that is just a mouse-click away, which can only be a good thing.

“Nonetheless, I’m entirely happy that I learned the way I did. If information is less readily available then sometimes necessity makes you become more resourceful in the way you seek it and perhaps there’s something to be said for earning at least some of your knowledge rather than having it all spoon-fed to you.

“The biggest potential casualty in this age of information overload is surely the development of a good ear. This is a vital asset for any serious musician and the only way to nurture it, alas, is to force yourself to work things out the old- fashioned way every now and then.”

Why did you learn to play so many different guitar styles? Are you interested in all aspects of guitar playing or did you learn some styles purely for tuition or session work related reasons?

“I’ve always felt that music is a language and that styles are just analogous to different dialects or regional accents, rather than being totally disparate entities. I’ve always enjoyed listening to a wide range of music so my instinct has always been to absorb everything I liked, rather than restricting myself to one specific area.

“That’s not necessarily a good or bad approach - I have a lot of respect for anyone who has the self- discipline to devote their whole musical life to, say, bebop - but I guess the range of stuff I chose to learn is just an honest reflection of what music means to me personally.

“Even beyond the guitar styles thing, I remember being very young when I had a lightbulb moment and realised that perhaps I could learn something from what all the other instruments were doing on a record, or that there was actually nothing stopping me from trying to work out how to play a TV theme, or the music I heard coming out of the ice cream van.”

Shred dead?

What guitarists continue to inspire you?

“All the guitarists who ever did inspire me, pretty much. If I’m about to listen back to some album that I found inspiring in my formative years but I haven’t checked out for a long time, there’s always that slight worry that I might have grown out of whatever it was that initially appealed to me.

"Perhaps the more imaginative technical players need to reclaim the word, or perhaps it would be simpler just to come up with a new one"

“In reality, that tends not to be the case. My familiarity with various melodic minor modes has in no way detracted from my ability to be amazed by Electric Ladyland!”

Marty Friedman said in a recent interview that it makes him cringe to be termed a ‘shredder’ and that he does not like being associated with the scene. Does such a description offend you as well?

“I suspect the meaning of the word ‘shred’ has actually changed slightly over the years. My original understanding of it was derived from a kind of underground community in the early 90s, and at that time, the word ‘shred’ seemed to represent the concept of pushing the boundaries of what was possible on the instrument.

“Put that way, it sounds like a noble enough pursuit, but now the same word mostly carries ugly connotations of playing fast purely for the sake of it, and there’s a widespread assumption that extreme technique and actual music-making are mutually exclusive, which I think is a shame.

“In reality, fast playing can range all the way from the tedious to the sublime, and it’s intriguing that no other instrument really seems to need a word like ‘shred’. Was Art Tatum a shredder? How about Michael Brecker? Eliot Fisk? Paco de Lucia? Well, perhaps the more imaginative technical players need to reclaim the word, or perhaps it would be simpler just to come up with a new one.”

The Aristocrats’ new album, Tres Caballeros, is available now on Boing! Records.