Glyn Johns on rock's golden era and his new book, Sound Man

"I'm not a perfectionist in the studio. The focus is on the emotion and the feel of the music."

Producer Glyn Johns on rock's golden era and his new memoir, Sound Man

When I meet producer Glyn Johns at his west London home, I'm greeted by a warm, welcoming and laid-back figure who, with his funky glasses perched at the end of his tanned nose and a glorious shock of white hair, could easily pass for a hip college professor rather than the studio wizard who presided over a host of seminal projects by The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, The Who, the Eagles, Eric Clapton and the Small Faces, among others, during the audaciously creative and wildly over-the-top era of ‘60s and ‘70s rock.

Johns has chronicled his astonishing career in a brand-new memoir, Sound Man, which charts his serendipitous rise from London choirboy to top-tier producer. Along the way, he also recounts some of his more colorful adventures with some of rock’s most celebrated eccentrics like Keith Moon, John Lennon and Keith Richards.

The book shines a light on John’s interpersonal skills and his exhaustive work ethic, character traits that proved crucial to his success in dealing with the world’s most mercurial musical forces of nature. Additionally, the revealing tome deftly captures a period when music was such a defining and ubiquitous art form that it both mirrored and shaped popular culture.

In the following interview, Johns talks about his role in shaping classic rock as we know it, why he thinks Zeppelin’s debut is their best record and what he would do if Jimmy Page wanted to work together again. Sound Man will be published on November 13 by Blue Rider Press, a division of Penguin Random House. You can pre-order the book on Amazon, Barnes & Noble and IndieBound.

Any trouble remembering instances from 30, 40 years ago?

“That was down to my keeping strict work diaries about everything from studio times, expenditures and dates plus trips back and forth to America, which I logged meticulously. So those notes enabled me to write the book extremely accurately, because I'd not thought I was capable of writing a book. But my publishers and [writer] Bill Flanagan convinced me that I could.”

“I set out to make an observation of the industry I was in for the past 50 years and how, from my perspective, it had changed. It's not meant to be an autobiography, nor is it salacious. My involvement with The Beatles was short but relevant to me. Plus, it was fascinating for me to be involved with these amazing, brilliant people."

Maybe you could remember things so well because you weren’t taking drugs, which you point out in the book.

“As much as some people find it bizarre that I was so straight, I was. It was crucial that, in order for me to do my job, I needed to be totally compos mentis. I'm very meticulous about how I run things in the studio, and I'm quite organized. It wasn't even a struggle for me to refuse drugs, and the more I saw what all of that did to people, the less I wanted to do it. But I'm not a perfectionist in the studio. For me, the focus is on the emotion and the feel of the music, so I've never sought perfection in that regard.”

You took it on the chin during the contentious false starts of The Beatles' Get Back sessions. You write that "Phil Spector puked all over Let It Be" – a lot of Beatles fans would agree with that.

[Laughs] “Anyone's career has disappointments, and I hope I learned from mine. But, like life itself, you have ups and downs. When I started in the industry in the early ‘60s, fortunately, few music executives were involved in the studio scene, and that lasted for years, thankfully.”

On label interference

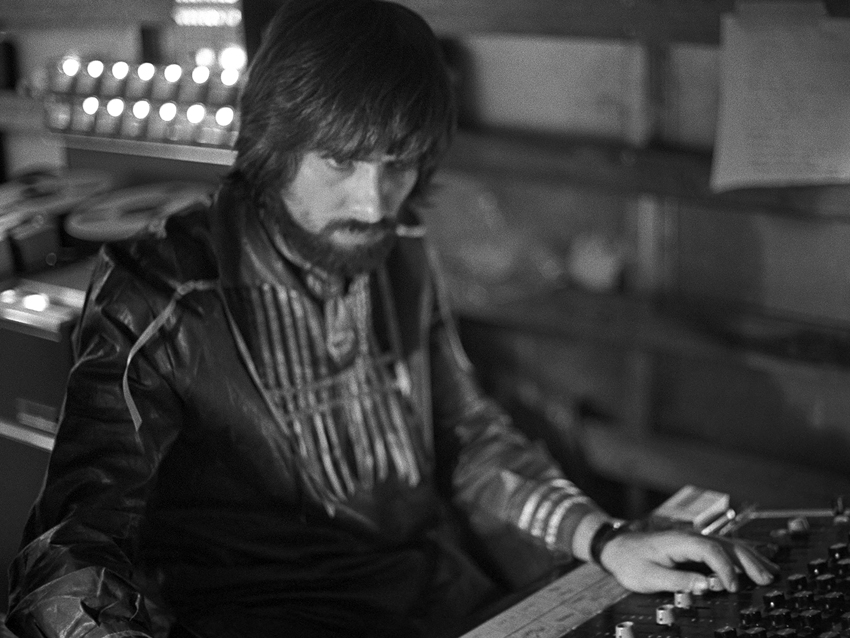

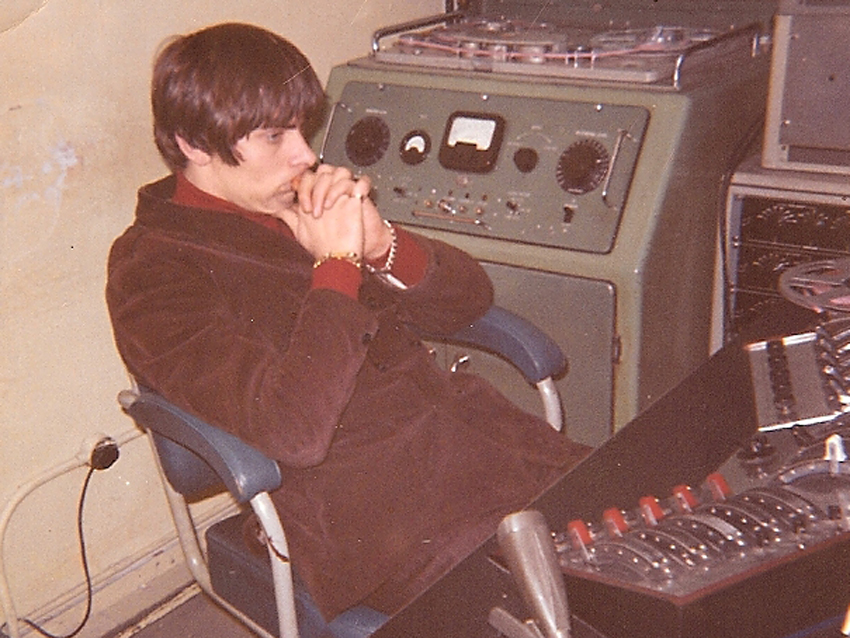

Above photo: Johns at IBC Studios, circa early '60s.

Comparatively, you wouldn’t have the same kind of creative freedom today that you did back then.

“When I started, it was an extraordinary time creatively for artists, and executives gave people like me a free reign. I was particularly fortunate as I had no relationships with A&R people, whereas nowadays, and in the recent past, you have a lot more interference from A&R.

“A lot of the acts I worked with back then were making their first albums. Today the expectations are different. Nowadays, if you make an artist's first album, you'd get a tremendous amount of interference from the label. If I get a call today from a label executive, I'll discuss with them what I can deliver to an artist. If we agree to my producing, I'll finish the album as best I can, and the label will then receive it as such. If they are not prepared to do that, I'll understand and not take the job.

“But I don’t want to be told how to produce a record. If you want to tell me what to do, then you should produce it yourself. To my knowledge, no one has remixed one of my records, so I’ve been lucky. In comparison, my son Ethan, who is both a producer and musician, experiences way more interference than I ever did, and of course, that makes his job a lot more difficult.”

Sound Man doesn't make too much of a distinction between the roles of producer and engineer. Would you say that record producers are more like film directors – you're responsible for the whole picture?

“You hit it right on the head. It’s close to a film director, more than anything.There are both creative and budgetary responsibilities in this role. The roles of the producer are as follows: His first duty, in my opinion, is to represent the artist where he is are creatively at that given moment in time. If he doesn't see eye to eye with what that artist requires, then he shouldn't be there. So he's responsible for helping the artist select the material that's recorded, helping come up with arrangements, supervising the performances of everyone in the studio. Basically, you facilitate – and everyone is unique and requires different levels of that.

“Back in my day, there were no freelance engineers. We all worked for a studio, and engineers recorded the music the way they wanted to and got the sounds they wanted. Some producers are quite open to the engineer's sonic ideas, whereas others are strict. Invariably, there are differences of opinion about the volume of voices, whether there should be echo on the voices or not, but that stuff is usually determined by the producer.”

On Led Zeppelin's debut album

Some artists required minimal input, like Led Zeppelin. Talk about your relationship with Jimmy Page during the making of Zep’s first album.

“Jimmy and I both grew up in the same town in south London, and we even had a little band together for a short time. I’d got him a few sessions in the ‘60s, and when he decided to put Led Zeppelin together he asked if I was interested. The sessions were actually booked under the name The Yardbirds, and I had no idea what it would sound like, but when they started playing I was completely blown away.

“I don’t think I’ve come down yet from the staggering buzz I got from being in the room; it was unbelievably inspiring and incredibly easy to record. They were well rehearsed and masters at what they did, which is why it took only nine days, including mixing.

"We were putting the Stones’ Rock And Roll Circus together around the same time, and I took an acetate of the album into a production meeting. I told them ‘This is going to be huge,’ but Mick Jagger wasn’t interested in hearing it, so I dragged George Harrison into Olympic to listen to it on the way back from a Beatles session. He didn’t get it, strangely. I still think that album is their best. It shook everything from the roots. But they were an example of a band that didn't need much input from me, and aside from recording them I kept my jaw on the floor throughout those sessions, just floored by their natural talents."

You mention your disappointment at not working with Joni Mitchell. Were there other artists you wanted to produce but didn’t?

“Absolutely! There are numerous occasions when I'd wanted to work with artists who impressed me enormously – the Beach Boys, The Band… Little Feat, who I tried to bring back together after Lowell George died. Equally, as I say in the book, it was probably a good thing that I didn't work with Tom Petty And The Heartbreakers as I wouldn’t have enjoyed the records as much if I'd been there.

“When you hear music that you haven't worked on, you have fresh ears and you only relate to what you hear – not the work of getting the sounds or the songs down. I still listen to some of the music I work on, occasionally, but it's a different experience. That's why I'm happy to mix other people's albums: You come to it totally fresh, with no idea of the particular experiences in the studio to achieve the sounds."

You write about some of the tragic figures you've worked with – Keith Moon and Brian Jones. Did you remove some controversial events from the book?

"Yes. I initially made a list of topics, anecdotes and memories that I considered including. A few weeks later, I realized that some of the negative stuff wasn't really necessary to tell my story, so I edited it out. I realized I was venting my spleen for my own purposes. In the end, I tried to be honest without negativity or judgement."

What he looks for

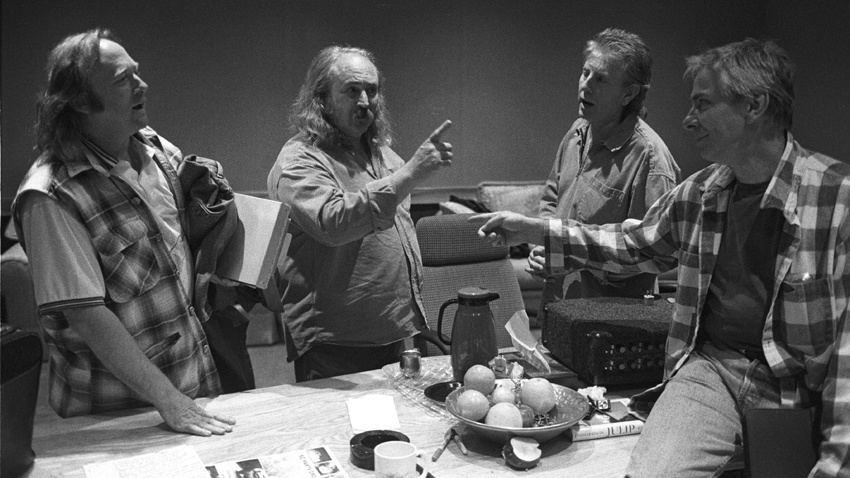

Above photo: Johns (right) with Stephen Stills, David Crosby and Graham Nash.

What attracts you to a musical project? Is there one thing in particular that you look for?

"Invariably, it's always the songs that are my biggest consideration. The other big factor is the personality of the individual or the band. That connection is vital. It's quite a demanding job. When you work with an artist, that album will be a big part of their lives for a long time. And you have to remember that their career is on the bloody line, whereas I'm on to the next thing once we’ve finished. So there must be a real understanding and good communication between the artist and myself."

The Glyn Johns method of drum miking, using just three mics to record a drum kit, has been revered, scrutinized and imitated since you first worked with John Bonham. People are still trying to capture that sound.

"Often the drummer in the band I'm working with wants me to make him sound like Bonham. I can't do that because he’s not Bonham. Although I can't fulfill that expectation, you don't want to let people down. I do find it strange to go online and see hundreds of videos on this technique – I don't know where they got their information. It’s never been about using a ruler to get exact measurements from the drums to the mics; it’s about tuning the drums correctly and then keeping things simple. To a minimum nowadays, they put 54 mikes on a drum kit, and then the drummer's sound is gone.”

How was the money back in the day as compared to now?

"You’d get a generous advance against a royalty. In those days it was very good, because even if the record didn't sell, your advance would certainly cover you for your time and then some. But today, with such diabolical record sales, it's not true anymore. Even advances are tiny now as there's just no money around in music."

Can budding engineers and producers rise up in the ranks now as you did then?

"The entire business has gotten much smaller. However, I do hope that if a young person does read this book, and if they have aspirations, that they will learn from me. When opportunities do present themselves, you have to pluck them and just go with it."

Picking hits

What is the best aspect of your job?

"Honestly, I can't choose one because the entire process is fascinating to me, from meeting with the artist initially to feeling each other out and through all the stages of recording until completion. I think choosing the right producer is one of the hardest things an artist must do, because you never know how much a producer really did on a previous album. You have to place a lot of trust in a producer, so there's a high level of expectation there.

"One thing I’ve never been good at is choosing songs. That would be among my least favorite tasks. But if there is one thing I especially enjoy, it's the tremendous gratification I get from witnessing great talent performing."

Have you heard from any of the musicians in the book? You stated that you hoped Eric Clapton would be receptive to resuming your friendship.

"I've gotten lovely reviews from many of them including Eric, Paul McCartney and Townshend, and I've met up with Chris Blackwell after a 20-year gap. Eric and I are in touch again, and we've had a fantastic time catching up, having dinner out. I'm overjoyed to say that we're still friends."

You gave your younger brother Andy Johns his start in the business. He, of course, went on to huge success as an engineer and producer.

"Yeah, I got him his first job at Olympic Studio, but he was chronically late and got fired. I was the opposite and took after our mother while he took after our dad. But Andy was an absolutely brilliant engineer."

You don't work as much as you once did. Is that by design?

"I've certainly not retired, and I still love it. And, for once, I've got a full life outside of the studio, so I keep very busy. The day I don't learn in the recording studio is the day I'm done."

If Jimmy Page rang you up and asked you to work on his next project, would you be open to that?

"Yes, of course."