Gibbons, Ford, Lopez, Lukather and Trout talk Supersonic Blues Machine

In-depth with the all-star blues guitar group

Introduction

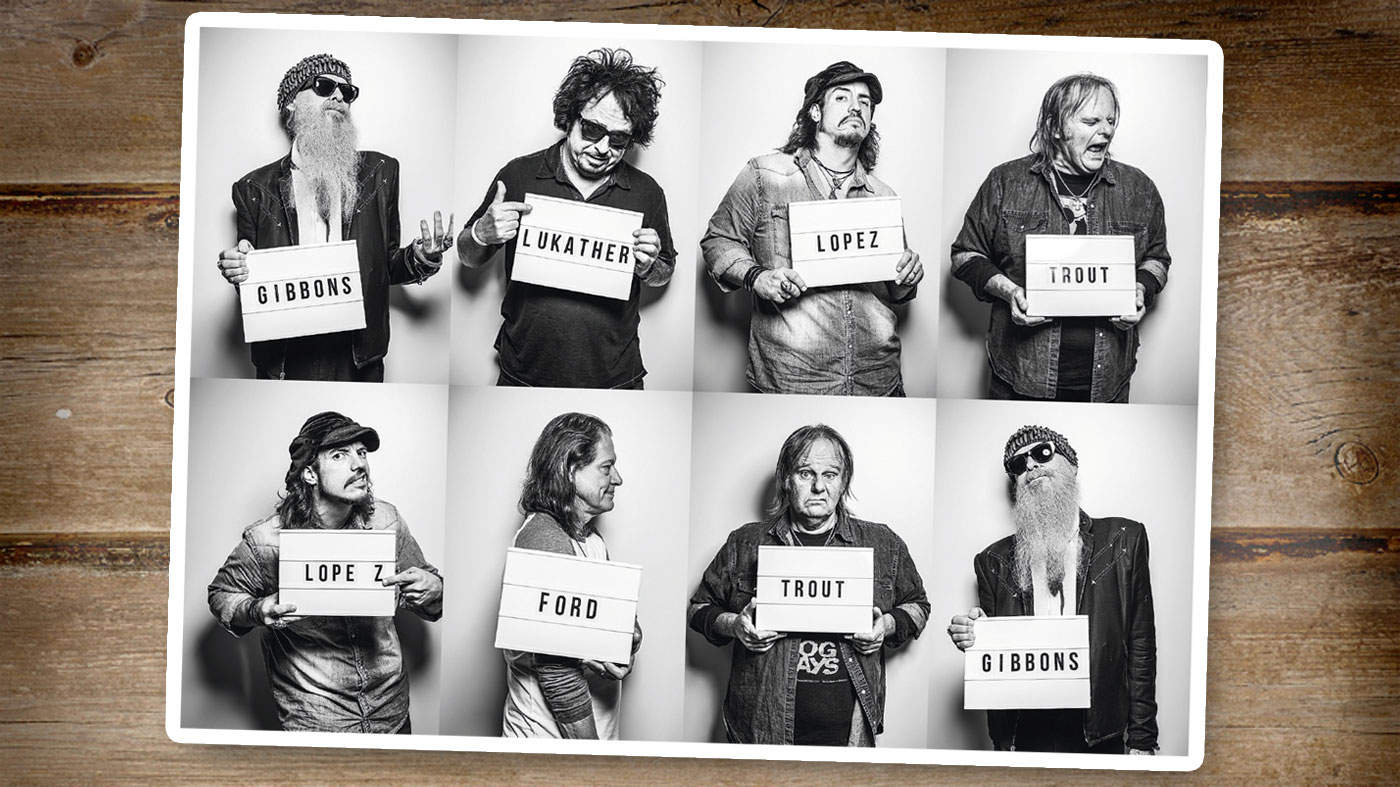

The line-up of Supersonic Blues Machine reads like a guitarist's answer to the Dirty Dozen. Masterminded by ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons, the band’s musical muscle is provided by the cyclonic guitar playing of Texan blues-rocker Lance Lopez.

As if that weren’t enough, the band’s debut album, West Of Flushing, South Of Frisco, also boasts outstanding performances from Walter Trout, Eric Gales and Robben Ford - while Toto virtuoso Steve Lukather has joined the group’s live act. We join this extraordinary gang of guitarists to talk about tone, technique - and the soul-redeeming, all-healing power of the blues...

We join this extraordinary gang of guitarists to talk about tone, technique - and the soul-redeeming, all-healing power of the blues...

Like something from the plot of a Spaghetti Western movie, Supersonic Blues Machine - the most intriguing blues supergroup of recent times - was formed when some of guitar’s greatest gunslingers were recruited one by one to join a project that has enjoyed a curiously charmed life since its inception.

The story begins with Lance Lopez, a hard-hitting New Orleans-born guitarist who grew up in Texas, thereby combining two of the greatest schools of the blues in his upbringing. Over the years, Lance supported the likes of BB King and ZZ Top, and Billy Gibbons of the latter group became a friend and mentor.

As Lance toured his solo material, another fortuitous thing happened. Lots of people, from fans to promoters, urged him to meet one Fabrizio Grossi, an LA-based bassist who had also worked with Billy Gibbons. Everyone seemed to think they’d make a great musical duo.

After this happened a positively uncanny number of times, Lance decided to co-operate with the inevitable and journeyed to Los Angeles to meet Fabrizio. In the space of just one afternoon they became “like brothers”, Lance recalls and the nucleus of Supersonic Blues Machine was formed.

Then another lucky chance occurred - Billy Gibbons had written a song he no longer needed that he felt would be the perfect starting point for an album of hard blues-rock by the fledgling outfit. Lance and Fabrizio accepted Gibbons’ offer with gusto and set about recruiting more guitar legends for that album, which became West Of Flushing, South Of Frisco.

And what a line-up it is. From California they recruited revered bluesmen Walter Trout, recently recuperated from a near-fatal illness, and Robben Ford - plus Toto factotum Steve Lukather. From Memphis came blues-rock heavyweight Eric Gales and from Texas came Billy Gibbons himself.

We were welcomed to the machine - which Lance and Fabrizio hope will become a kind of travelling circus of legendary blues guitarists - as they prepare to perform for only the second time, at Notodden Blues Festival in Norway. Sadly, Gales isn’t present on this occasion, but the other luminaries are all too ready to talk about what matters in guitar - from playing with all your heart, to which boutique amp makers do the best take on British Blues tone. So, strap in for take-off…

Don't Miss

Billy Gibbons picks his standout moments from a 47-year career with ZZ Top

Robben Ford talks Butterfield, blues and breaking in SGs

Lance Lopez

He’s one of the most hotly tipped blues guitarists around - but Lance Lopez paid his dues backing legends such as BB King and mentor Billy Gibbons. We join the Texan tornado to settle the Gibson-versus-Fender dilemma and learn how this connoisseur of British blues tone dials in his incendiary sound…

There’s something joyous in the Supersonic Blues Machine album, as well as hard-hitting. Do you feel the blues has been a redemptive force in your life?

“Absolutely. The beautiful thing about the blues is that it’s so personal and so emotive and it taps into that place. I’ve definitely found it to be healing and absolutely redemptive. And to hear Walter’s struggles about coming through his illness and learning to play guitar again… you’re thinking to yourself, ‘Wow, this is Walter Trout.

Blues is a music of survivors. It literally is - it’s either about having survived something

“How does Walter Trout have to learn to play guitar again?’ But he did it. And I think that was also part of his healing from his illness. I truly believe that. That drive and that inspiration to get back to where he was truly healed him physically as well.

“Blues is a music of survivors. It literally is - it’s either about having survived something, or what you’re going through at the moment that you’re going through it. But we didn’t want to make an entire record of minor key, slow, sad blues songs, because a lot of it was about what we had recovered from. And you shouldn’t listen to the blues and feel worse than when you started!”

How did you first discover the blues?

“Well, I was born in Louisiana and I was surrounded by blues, but I had no idea. I can remember riding with my father in the car with the windows rolled down and halting at a stoplight and seeing an old black gentleman sitting on his front porch with a straw hat and the Dobro and the slide, playing and singing, and people on the front porch with him were drinking and laughing. And I was just like, ‘That was the greatest thing I’ve ever heard in my life.’ And didn’t know what it was, just that it was the greatest thing I ever heard. So, just regionally, we were surrounded by it and I had no idea - I was just drawn to it.

“Upon moving to Dallas, my mother actually took me to see BB King, who was playing with Stevie Ray Vaughan. When we got there everybody was wearing these t-shirts that said ‘SRV’ and I went, ‘What does SRV mean?’ I had no idea who Stevie Ray Vaughan was and he actually came out and played some Hendrix and I thought, ‘Wow!’, because he was the first guy I’d ever seen cover any Hendrix music back then. And then when BB King and him played together I said, ‘Okay, man, this is where I need to head.’

“But actually what I did, the very next day I went and I put my electric guitar down and started over on acoustic and started to listen to Robert Johnson and Son House… so I started over on country blues and I worked my way through the whole lineage, and that began a long study of country blues and Delta blues.

“And that was late 80s or early 90s, so there was no internet or any of that back then - you had to go to record stores and stuff like that. That was when the grunge thing was happening and starting to kick off and I was asking for records from the 1930s! So, I was like this weird little kid listening to Blind Willie McTell and all those guys.”

You started out playing a Strat but now you seem to gravitate more to Gibsons…

“Well, I was a Stratocaster player all through my youth. But there were some nudges that I received, the first one being from BB King. I opened a show for BB King in 2000 or 2001, something like that. I was using a Strat then and BB commented that I should really consider trying a Gibson guitar and I said, ‘Well, I actually have a couple of Les Pauls and a Flying V,’ and he said, ‘Well, I’d be interested to hear you playing them.’

My workhorse amp is the Marshall JCM2000 DSL100. Jeff Beck turned me on to that

“And so that was kind of like, ‘Wow.’ At that time, the standard issue for Texas blues was a Stratocaster from ’57 to ’62 kind of era and a Super Reverb or a Bassman. That dominated Texas - that’s what our sound primarily consisted of - and if you came in with a Les Paul it was a weird thing! But I was the kid that did sometimes show up with the Les Paul and they’d be like, ‘What are you doing with that thing?’ and I’d be like, ‘Well, it’s because of Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page.’

“And then the next nudge came from Billy. I was out doing shows with ZZ Top and he would help me dial in my Marshalls and we’d look at the guitars I had with me on tour. And when I switched over to my Flying V or a Les Paul or something, that’s when he would say, ‘That’s it - that’s you.’ So, now, if you listen to the Supersonic Blues Machine album, there’s all kinds of guitars on it. But for an all-round guitar, my R9 is just rock solid.”

You’re a connoisseur of British blues tone. What are your favourite amps?

“My workhorse amp is the Marshall JCM2000 DSL100. That’s what we have as backline here in Norway. Jeff Beck turned me on to that amplifier in 2001 when I played a show with him in Germany. I had all these old Plexis and he was like, ‘Oh, man, this is so much easier to use and you don’t have to kill everybody with volume.’ And I was totally floored with that amplifier and how versatile and consistent it was. So, that’s why the DSL100 is my workhorse amplifier and that’s always the first choice if I have to hire backline.

“As far as rigs that I use at home go, I have a few things. First, there’s the Bogner Helios 100 that’s basically a Plexi with all of Reinhold Bogner’s knobs on it, so it has a switch that toggles between JTM45 and Super Lead 100-style tones. And he’s also packed the amp with all of the mods he did for Van Halen and George Lynch and Jerry Cantrell.

The next of my go-to amps is the Scorpion, which is built by Mojave Ampworks in California

“Reinhold knew that I was a hardcore vintage Plexi connoisseur and he also knew that I struggled to get a Plexi to sound good in a small club, where even a 50-watt felt very loud. It was cool that it was a head where I could have an amp that sounded like a JTM45 with a little extra gain on it, but if I was in a big room I could get it to sound like a Super Lead 100. And it’s a good 100 watts - it’s not like my old 1970 Marshall Super Bass, where it’s so loud you can’t hardly be in the room with it.

“The next of my go-to amps is the Scorpion, which is built by Mojave Ampworks in California - actually, it was Billy who hooked me up with Victor Mason. At the time, Billy was using a rack-mounted version of the Scorpion. It’s a very cool amp that’s based on a 1968 Super Lead 100, but it has a 100-watt transformer that’s rigged to run at half power.

“So, it’s a 50-watt amp that has what they call a dampener built into it, which is one of the best alternatives to a traditional attenuator I’ve ever heard. That was the first amplifier that Billy introduced me to as a means to get that Marshall-style sound in a club where volume issues are dominating. And that has remained a cornerstone of my sound.

“And then there’s the relationship with [amp-maker] Doug Sewell from Dallas. I’ve known Doug many, many years and he was a Fender-style amp builder, because he was based in Texas, where Super Reverbs were so popular. It was really cool when he went to PRS and started building EL34 amps and that really excited me, so another amp that got used a lot on the record is his PRS Super Dallas. And it’s a really great 50-watt amp, with two EL34s. I actually have a cabinet for it loaded with four 10-inch Greenback Celestions. I found that to be a very interesting combination.”

What are your favourite speakers for blues-rock tone?

“I love Alnico Blues and I love Greenbacks, and I’ve actually been using Creambacks. For my Helios, I have a 212 that I take out that’s an open-back like a Bluesbreaker and I’ve got a 65-watt Creamback Celestion on one side and a Vintage 30 next to it. That’s a really cool combination. And then in my 412 cabinet, I have two 65-watt Creambacks plus two 75-watt that are in an X-pattern.

Billy would say, ‘Your playing’s gotta have groove and feel.’

“I like the Creambacks because I can push them. If I run a drive pedal with lots of low end, using the neck pickup of a Les Paul, they won’t blow it. Because I’ve blown a lot of Greenbacks! Don’t get me wrong, the Greenbacks are fantastic with a Les Paul - but you gotta just plug straight in and turn it up. But I’ve tried that with pedals and then... there goes the Greenback [laughs]!”

Billy Gibbons has been a real mentor to you. What’s the best advice about guitar playing that he’s given you?

“Oh, man, it’s always about striving to get the best sound you can. Because it really doesn’t matter what you play, or how fast you play… if it doesn’t sound good then it’s not gonna be good. That was always the number one thing. And then he said, ‘You gotta play what makes you happy - you gotta be able to play with feel and with heart, and it has to make you feel good.’ Thirdly, Billy would say, ‘Your playing’s gotta have groove and feel.’

“A lot of that boiled down to making sure that you got a groove established in the song and that what you’re playing lead-wise should also groove - instead of just flying off the handle and throwing lots of notes out. Because when I was a young man, that’s what I was doing [laughs]. But Billy saw me as a kid and he said, ‘You gotta groove’, and I’m thinking like, ‘What, a funk groove?’ But he said, ‘Go listen to You Don’t Have To Go by Jimmy Reed.’ So I listened to Jimmy Reed and it was like, ‘Ohhh, that groove.’

“That’s when it started to make sense - and then it was about putting the lead patterns around that to where it was just interweaving with the groove and not just blowing over the top of it. Tone, playing with love and groove… those are really the three main insights that I’ve got from Billy. I’m just so grateful to have the relationship that I’ve had with him and now to be involved in a musical unit with him is just awe-inspiring.”

Billy Gibbons

His riffs evoke the juke-joint grooves of 40s blues and are as hot as the Texas desert, but ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons is as cool as the chrome on a hot-rod Ford. We meet the brujo of Marshall tone to discuss modded SGs, boutique amps and hear how a forgotten rap hit kicked the Supersonic Blues Machine into life…

You and Lance Lopez are both Texas bluesmen. What are the hallmarks of that style?

“Well, we could cite the usual list of suspects for inspiration that goes back to that sweet spot from ’49 to 1959. But the blues has a habit of growing back into popularity every 10 years; it changes slightly but that thread of bluesiness somehow manages to remain.

I wouldn’t call Supersonic Blues Machine traditionalists, but that thread does exist

“Even by contemporary standards, if you listen to our buddy Dan Auerbach from The Black Keys, they call themselves a rock band. But you listen to his singing style and certainly the two of them together, they play pretty much in a bluesy fashion. Same with Royal Blood - you know those two guys?

“So, I wouldn’t call Supersonic Blues Machine traditionalists, but that thread does exist. Someone said, ‘Why do so many guitar players come from Texas?’ I can’t figure it out. I think there’s nothing else to do but play guitar. It’s like, you want to learn drums, go to Cuba. Guitar, Texas.”

Your sound is built on a foundation of Marshall tone. How did that originate?

“The Jeff Beck Group came through Houston, Texas - and that was with Rod Stewart, Ronnie Wood on bass, Nicky Hopkins on organ - and they were using the Marshall 1968 Super Lead 100. Jeff was playing a Sunburst Les Paul and Ronnie Wood was playing a Fender Telecaster bass that was the reissue of the early Precision. But that Marshall sound was insane.

“We were just coming out of the Moving Sidewalks into ZZ Top and it happened that Jeff didn’t have transport to go from Houston, Texas to Dallas, Texas for the next night. So I said, ‘Well, I’ve got a truck, we can take your stuff up,’ so I was Jeff’s roadie for one night [laughs]. The gear manager. But in return I said, ‘Jeff I really like these amps,’ and he goes, ‘Oh, yeah. That’s from Jim Marshall. Would you like to get some?’

“He arranged for ZZ Top to get the first Marshall amps in the US. Here’s the photograph [Billy produces a picture of himself standing in front of a Marshall stack with a Firebird I]. Jim Marshall, before he passed away, was very upfront, and he said, ‘I don’t think I was doing anything that much different - we were taking the standard schematic right out of the 1936, 1933 RCA book.’ Fender did it, Marshall did it. But I believe that using British components did add something different. Which was one of those magic things that just happened.”

In recent months we covered Clapton’s playing at the time of the ‘Beano’ album and Joe Bonamassa questioned whether he in fact used a Dallas Rangemaster - or if it was simply the amp running flat-out. What’s your view on that?

“Of course, the word ‘Bluesbreaker’ came from that record, but the Marshall on the back of the sleeve was the 18-watt combo. Later, Marshall made the 45-watt combo and they named it the Bluesbreaker. But that was long after the 18-watt had been made. I got lucky and found an 18-watt with two 12-inch speakers.

“Most of the 18-watt versions were 210s - the less-common ones were 212s. In fact, the one that I’ve got runs on 220 volts and the speakers are Celestions made at Silverdale Road where the factory was located. It’s got two original Silverdale Road speakers and this thing sounds just like the ‘Beano’ sound.

“I actually went to the office of the company that publishes The Beano - the comic book - and they have racks of back issues going back. And the secretary she came back and she goes, ‘We don’t have that one - but we have it in our museum. We have one.’ And we said, ‘What would it take to borrow it for one hour?’ So, we took it down to a copy shop and we came back with a stack just of the cover page. And we returned it, of course, but I got one signed by Clapton. He saw it and said, ‘Ah, I’ll have this,’ and I said, ‘Don’t worry, I’ve got another one.’ [laughs]”

Quite a few boutique amp makers have been inspired by Plexi tone. Have you found any gems among the new generation of Plexi-style amps?

The magnetic appeal of what Marshall created has stimulated the search [for a hot-rod Plexi-style sound] by a number of other companies

“You raise an interesting point. The magnetic appeal of what Marshall created has stimulated the search [for a hot-rod Plexi-style sound] by a number of other companies. I don’t think anything will replace Marshall, but as far as favourite amps in that style go, Dave Friedman has the Pink Taco - which is a little 18-watt with master volume and effects loop.

“Two very interesting additions that have modernised the 18-watt and taken it into utility. As did Magnatone: they have a combo version of the Super 59 - I don’t know if they’re offering it officially yet - but I got Ted [Kornblum] to make a combo version of the head and cab. It was nice.

“The top five combo amps of that kind are, in my view, the 18-watt 212 Marshall from 1965 to 1966. Maybe 1967. Then we’d have a Magnatone Super 59 and Dave Friedman’s Pink Taco 18-watt. Then there’d be Mojave Ampworks. They’ve got an interesting line of anything you can imagine. And we’ve left out another sleeper - which was Selmer’s Zodiac 50.”

They used to be quite easy to find in classified ads a few years ago…

“Try and find one now, though. There was another Selmer with less wattage, about 20 watts, but I think Peter Green may have played through a Zodiac at one time.” Turning to Supersonic Blues Machine, we hear that a rap track that you adapted for the blues sparked off this whole glorious endeavour…

“Well, Fabrizio and I had been working on a couple of projects - songwriting. At the time, ZZ Top was wrapping up the sessions that were released as La Futura. I was working as co-producer with Rick Rubin. He said, ‘Do you think we could use maybe one more song?’ So I said, ‘How many do you need for the release?’ and he said, ‘We need 10.’ So I said, ‘Well, we have 20.’ He said, ‘Let’s do one more.’ I said, ‘Okay.’

“By this time I was producing most of the sessions in Houston, Texas, so I left California, went to Houston and the engineer said, ‘Now what?’ and I said, ‘Well, we’re going to do one more song.’ He said, ‘Gee, you already have 20.’ I said, ‘Well… 21.’ So they said, ‘What do you have in mind?’ For some reason [I suggested] a song from 20 years earlier by some Houston rappers, Fat Pat and Lil’ Keke, that was called 25 Lighters, that was a pretty big hit. They said, ‘25 Lighters? That’s a rap song.’

“And I said, ‘Yes.’ That was Joe Hardy, the engineer, thinking, ‘Gee, how are we going to go about this?’ Well, [writer and engineer] Gary Moon was in the lounge and through the door I said, ‘Hey, G, what are you playing on the computer?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I’m watching Lightnin’ Hopkins videos.’ I went in and looked at it and then this blues thing got in. I came back into the control room. I said, ‘Let’s go.’ I said, ‘We’re going to take 25 Lighters into blues lounge.’

I said, ‘I know Lance. He’s one of my favourite guitar players. Put a band together,’ so they did.

“I mean, it was such an odd twist, but it sounded okay. It was ‘ZZ-approved’ because it had that bluesy element. I sent it to Rick and he called me up and said, ‘I love this thing. What does this mean?’ I said, ‘Look it up on the Google search for 25 Lighters and there’s a definition of what that means.’ I’ll leave the reader to go look it up. Anyway, the record company was very excited, but Fat Pat and Lil’ Keke had died in the meantime and what I had made was a derivative of their work, so it required approval - but no-one knew where to find the estate, so the song was in limbo.

“Now, this is interesting: around that time ZZ Top was approached by a whiskey company, Jeremiah Weed. They said, ‘We would like ZZ Top to help us promote our whiskey. We have heard about this song called 25 Lighters, which you now call I Gotsta Get Paid.’ I said, ‘Yes, but we’ve got a problem. We have not received permission to release it. However, I’m going back to California to meet Fabrizio Grossi. I’ll write a song for you that will make sense.’

“I got with Fabrizio and I said, ‘Man, I’ve got a problem. They want to use I Gotsta Get Paid, but it’s not released. But I have written this song called Running Whiskey,” and Fabrizio said, ‘What is that?’ and I said, ‘Well, I’ve got a hot rod car called the Whiskey Runner.’ He said, ‘What does that have to do with the song?’ so I said, ‘Well, back in the 1930s the Moonshiners would make the whiskey, they put it in the fast cars to be able to outrun the law.’ And he said, ‘I get it, I’m running whiskey - yes, okay.’

“We recorded Running Whiskey the same day we found the estate holders. The wife and the daughter heard our version of 25 Lighters and they said, ‘Oh yes, we like this. Good.’ So, then Fabrizio said, ‘What are we going to do? This Running Whiskey is a good song.’ I was sort of joking, but I said, ‘Well, you need to record nine more.’ And he said, ‘I’m working with a guitarist from Texas, Lance Lopez.’ And I said, ‘I know Lance. He’s one of my favourite guitar players. Put a band together,’ so they did.”

Billy Gibbons guests on the track Running Whiskey from Supersonic Blues Machine’s album, West Of Flushing, South Of Frisco.

Robben Ford

Robben Ford is, for many, the finest guitarist working today. His poised and soulful playing style is enriched by jazz but deeply rooted in the blues. We joined Robben to talk about Dumble tone, Tele pickups and to receive a personal masterclass in how to solo with more musicality and fire than ever before…

How did you get involved with this meeting of blues minds?

“I met Fabrizio for the first time a little over three years ago. He connected me with Mascot Records and I wound up signing with them so that was very nice. He sort of asked me out of the blue if I would be interested in that. Steve Lukather I have known since he was 19 and I don’t even remember how old I was at the time when we first met. I think the only time we have ever played together was just a few years ago. We went to Japan with Bill Evans and Randy Brecker, Soul Bop, and did some shows in Japan.

“That is the only time we have ever really played together. We are not even playing together here - we are on the same stage for a minute. And Billy Gibbons I met once, a long time ago. He actually came to one of my shows. He came backstage and said, ‘Hello, I don’t know if you know this, but you and I are born about three and a half hours apart…’”

Really?

“Yes, we are born on the same day. Same year, same day. He said he was born around 8:00am. I was born like 11:30am [laughs].”

You’re known as a player who straddles the divide between jazz and blues. Is there a meaningful boundary between the two styles on guitar for you?

That is the great thing that happened on the electric guitar; the expression finally came in that you don’t really get out of bebop jazz guitarists

“In a way, there is a real difference. In a sense, jazz guitar is probably the least expressive instrument of them all, if you think about the way that it was initially approached: big body guitar, rhythm pickup… it was a rhythm instrument. When people started soloing, there was that kind of monotone that exists in jazz guitar, which is one of the reasons why I didn’t listen to it.

“Actually, I listened to some - but really the only recorded jazz guitar I listened to a lot of was Wes Montgomery’s A Day In The Life. You probably know it. That record is unique. If you listen to the records he did before that with Riverside and the organ trio, they were very different. But even him… I hear one or two things and I lose interest. I do. I start wanting to hear something else. But that is not the case for me with tenor saxophone, for instance.”

It’s hard to think of blues guitar without bending. Exaggerated bends can be a blues cliché but, done properly, they bring a vocal quality to blues guitar...

“Yes, that is the great thing that happened on the electric guitar; the expression finally came in that you don’t really get out of bebop jazz guitarists.”

One of the easiest traps to fall into when you’re playing blues is to max out the intensity of your soloing straight away and leave yourself nowhere to go. How do you avoid that?

“Play shorter solos. Seriously. I play until I know that I am really pushing past myself. There is a point where you can emotionally go a little further or at least you think you can. Actually, I don’t spend my time really bending notes a lot. I do, but I am more focused on chords and harmony. That is what really interests me.”

Who would you class as your biggest musical inspiration?

“If there was any one artist I would say that I am most influenced by and that I play like him, I’d say Miles Davis. I don’t mean that anywhere near like I am as great or anything like that. But that is the real school for me. He was never a really great bebop player - but he had a beautiful sound and was really harmonically hip. He made the most of the way a certain note sounded against a certain chord. I really ran with that.

That, for me, is the thing. I like a good song. I like to play the note that sounds cool against a chord

“It’s wonderful when you find people who show you that you don’t have to play all of that stuff [histrionic, over-busy playing]. You just don’t. In fact, it is better if you don’t. I really feel that way. I would rather listen to Miles Davis than many, many other great artists.

“That, for me, is the thing. I like a good song. I like to play the note that sounds cool against a chord. For me, it is a lot more open. A friend of mine Bob Malach is a tenor player. He told me he was playing with one of the contemporary jazz-fusion guitar players, who said, ‘You play the melody and then you start your solo. And at the end of the solo, you see God.’ But if every song goes like that, it sounds the same.

“For me, it’s important to have a good song. There are more things to get your attention in a cool lyric. The song is a little journey, a little experience unto itself that is complete unto itself. There is a satisfying experience whether you ever take a solo or not. Then you add your improvisation to that, to whatever extent feels good.”

Given how many different ways guitarists have approached the blues over the years, how do you keep your blues playing fresh?

“Chords. That is how it works for me. I worked hard at becoming a songwriter. I try to create an environment where the guitar can do something that it hasn’t necessarily done before. A different atmosphere, a different feeling.

“In other words, the song is different. If you are playing shuffles and slow blues all night - which is what I did with Jimmy Witherspoon for a couple of years and Charlie Musselwhite for about a year - after the first few songs, you have done your thing. Even BB King sang most of the night, right? About 10 per cent of a night with BB King was guitar, even when he was younger. The blues is a vocal music.”

Do you think blues guitarists that sing have an advantage, in that you can do call-and-response between the guitar and your own voice?

“It’s hard work. I would rather somebody sang and I played! That is true call-andresponse: two different people, right? In my group I don’t do it. But we are not exactly a blues band. If somebody says, ‘What kind of music do you play?’ I say, ‘Blues and R&B.’ R&B opens it up a little bit. It is more songoriented. Rhythm and blues is songs. It’s not people taking solos. As I say, for me, it’s more a matter of playing a song. We’re not playing the blues or anything in particular… we’re playing a song that goes like this, but the background is strongly R&B.”

Let’s talk tone. Some blues players favour a clean, pure sound that slices through the mix. But others like to add gain so the extra compression helps each note sustain and sing. Where do you sit on that tonal spectrum?

When I have my sound together the way I like it, I play with a Dumble Overdrive Special. That is a very special amplifier

“When I have my sound together the way I like it, I play with a Dumble Overdrive Special. That is a very special amplifier. Sometimes, I feel I am not even able to talk about it in a way that would be meaningful.

“I’m not sure about that because of the uniqueness of the amplifier. Fundamentally, the guitar sounds like itself. That is what I like. I like my guitar to sound like itself and to have a sound curve that’s even all the way across. The lows, the mids, the highs: you hear all of them. They’re clear.

“From there, what I really like to do is just hit the boost. The boost on the Dumble, all it does is remove the EQ section. It’s this midrange boost thing: it doesn’t get woofy down the bottom; it doesn’t get too bright up on the top.

“It is just like, ‘Boom’ - powerful midrange. I can get everything I need right there. I don’t need the overdrive, I don’t need to compress it. Really, all I need is a little bit of reverb. And I use a short delay. I like a short delay, because it opens the sound up just a little bit. It kind of makes it a little bigger, sort of like doubling yourself. Then a long delay when I am playing quieter just to create that space.”

Last time we saw you play, you alternated between your Tele and an SG. Do you feel like you can cover it all with those two guitars?

A great Les Paul would be my first call if I had to only play one instrument the whole night. But they are just too damn heavy

“Well, honestly, I would be playing a Les Paul. A great Les Paul would be my first call if I had to only play one instrument the whole night. But they are just too damn heavy. But there are things about that Telecaster - it’s a ’60 - that you can’t really find anywhere else, particularly that rhythm pickup and that middle setting. But I play a lot of rhythm guitar on the treble pickup and I guess that is kind of unusual.”

You get a surprisingly round, full note from your Tele’s bridge pickup…

“Yes. I love that sound. To me, it’s brassy so it’s kind of horn-like. I moved to the treble pickup and play the treble pickup a lot, primarily because of Miles Davis. I grew up wanting to be John Coltrane. Of course, that was never going to happen, but the rhythm pickup turned up to the point of some kind of distortion is akin to the tenor sax, so I started moving towards the treble pickup and I kind of went, ‘Wow.’ And I think that’s because I listen to Miles Davis so much.”

Using a Tele bridge pickup like that is pretty upfront and in-your-face…

“Exactly, yes. That is a beautiful thing. That in itself is kind of a little challenge to yourself. It also works as a rhythm sound. A great rhythm sound. I will tell you one thing that I always forget, it was something I realised much later. Do you know the guitarist Buzz Feiten? Yes? Well, he played with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Did you ever hear that record? It’s called Keep On Moving. I saw Buzzy playing with Butterfield the first time, I saw that band many times. Three of those times was with Buzzy Feiten. I think he was 18 when he joined. He’s on the Woodstock video of Butterfield’s performance.

“Anyway, Buzzy played rhythm guitar on the treble pickup. That stuck with me. He was playing a 335, too, through a Fender Twin. That made an impression that I didn’t realise, because I wasn’t doing it then. It was like some years later I started playing more and more on the treble pickup rhythm guitar. I am like, ‘That is Buzzy’s sound, man.’ It is kind of interesting. That has happened a few times in my life where the influence was dormant and then it appeared like 10 years later or something.”

It was there all the time...

“Yes, waiting [laughs].”

Robben Ford guests on the track Let’s Call It a Day from Supersonic Blues Machine’s album, West Of Flushing, South Of Frisco

Steve Lukather

Toto’s legendary, garrulous guitarist is the joker in the Supersonic Blues pack, bringing his majestic melodic rock style to the band’s stunning live line-up in Norway. We join Steve to hear why “pain is pain” and discover how any guitarist can tap into the emotional power of the blues…

You’re not on the new album, so how exactly do you fit in with Supersonic’s flying circus?

“Fabrizio is a dear friend and [drummer] Kenny Aronoff has done a million sessions over the years. Fabrizio originally asked me to play on the album, but I just wasn’t available at the time, so I couldn’t do the record, but he said, ‘Could you come over and do the show?’ And so I said, ‘Yeah, man.’

I have the coolest life ever. I’m so grateful for it every day - I kind of wake up and pinch myself

“After this, I go home and back out on the road with Toto again for a month, then I’m going back out with Ringo again. I have the coolest life ever. I’m so grateful for it every day - I kind of wake up and pinch myself. I’m like, Jesus, man, 40 years later I’m actually busier than ever.”

You have legendary chops, so what’s your take on avoiding the trap of overplaying in a blues solo?

“We all love the flashy stuff. But at the same time, Dave Gilmour plays one note and it hits the back wall of the stadium. That’s what gets people on their feet. Shredding is great in a club if you’re up close, but if you’re far away, it doesn’t hit you like that. Back in my drinking days, I’d over-play and a lot of times when that happens it’s because you’re pissed off.

“I’m as guilty of that as anyone - people don’t realise that, though, on YouTube - and they’re like, ‘What the fuck? Why don’t you just stop?’ But I’d probably just had a phone call from my lawyer that’d pissed me off 10 minutes before I went on stage and so that anger came out.

“On a record, of course, I’m much more careful about taking a breath. Making a record is like a painting - you can sit back and look at it and live with it and come back the next day if you didn’t capture the magic in one take. But playing live is like driving Formula 1: if you bang into the walls you keep going. There are a lot of emotions that can occur on the road and if you’re pissed off, you’re going to dig in.

“I’ve been guilty of over-playing and as I get older I slap myself on the hand. I go, less is more, especially when you’re playing a big hall. That touches people. You don’t want to play to a sea of guys who have Guitar Center on the t-shirt and there’s no girls at the gig [laughs].

“I think Joe Bonamassa has managed to cross that line where both women and men appreciate it and he’s a very hard-working cat. We live near each other and he’s helped me refurbish my old ’59 ’Burst. And he’s a real student of the blues, even though he gets his balls busted. People say, ‘Oh, you’re not a real blues player.’ I mean, come on, man - none of us invented this shit. I mean, there should be a bunch of old black cats come back from 1920 and say you are all ripping us off! But if you have a few dollars in the bank from your career some people will say, ‘You can’t play the blues.’ Bullshit! Pain is pain.

“I think Clapton said that - that the blues has nothing to do with your bank account. I mean, you might have a sick kid, or lose someone close to you, or break up with your wife… I mean, we’ve all had the blues. So, you play from your heart and that’s why people are touched when you play less. And then when you step on the gas a little bit, it means something.”

Are there any fundamentals of the blues that are in danger of being lost as originators such as BB King pass on?

We’ve created a generation of guitar players who play in a very similar way to each other in style and vibrato and approach

“I think what’s lost now is that people get lessons on the internet. And so we’ve created a generation of guitar players who play in a very similar way to each other in style and vibrato and approach. Another thing that’s so overlooked is rhythm guitar and timing… not time as in sitting on a bed and playing along with a record, but playing with a real human being who may not have perfect time. Because then you develop this group time.

“That’s what gives The Rolling Stones their feel… you take Charlie, or you take Bill Wyman or you take Keith and if you take each individual guy sometimes it’s kind of loose. But when you put it all together it’s like a gumbo of the greatest grooves in the world.”

There used to be distinct regional differences in the blues, between areas of the US. Do they still exist?

“They exist, but I think people have brushed them over. It’s like when everything is on a grid and it’s perfectly timed and auto-tuned and everything, it’s like baking a cake and you take one bite and it’s all frosting and you think it tastes pretty good, but by the third bite, you’re physically ill, you can’t take any more.

“There’s something about having a rawness to it - and this is funny coming from the Toto guy - but we sat in the room playing that shit. It was us sitting in a room playing. We weren’t fixing things; we couldn’t do that. We’d spend a lot of time on vocals, but our tracks had honest mistakes.

“We grew up in studios and it didn’t feel weird, we didn’t get red light fever. But we’d still go back and listen to all the stuff we grew up with. And I’m still trying to go back and remember what it was like - right, that’s it. Like some old R&B records where the band created the funk, not just one person.”

Steve Lukather appeared as part of Supersonic Blues Machine’s live show at Notodden Blues Festival in Norway. www.bluesfest.no/en/

Walter Trout

Walter Trout has known the blues, all right. He fell ill with liver disease in 2014 and nearly died, returning from the brink after fans crowdfunded an organ transplant for him. In the process, he lost his ability to play, but then made the fightback of his life. Today, he’s playing with the intensity of a man resurrected

You’ve been through some difficult times, to say the least. Has getting involved with Supersonic Blues Machine spurred your recuperation?

“When I got the call from Lance and Fabrizio, I was just coming out of my illness, and when I got out of hospital I had to relearn the guitar. I couldn’t play any more, so I sat down for about a year and practised every day for four or five hours.

It was my first time getting back into the music world to go up to LA and record with those guys

“After I got out, I couldn’t walk. I was determined to play again and then my wife comes in and goes, ‘I just got an email. Are you interested in playing on a record with Billy Gibbons and Eric Gales and Kenny [Aronoff, drummer]?’ - because I did two albums with Kenny. I’m like, ‘Are you kidding? Where do I have to be and when?’

“It was my first time getting back into the music world to go up to LA and record with those guys. It was incredible to go and play and have them go, ‘Hey, that sounds great.’ It gave me some confidence back, because I was starting over. I was like, ‘Can I do this or not? I don’t know.’ It was a cool experience for me.”

And it happened at just the right time…

“The perfect time, yes.”

When you were recovering, how much of your playing ability had you lost?

“It was the whole thing. If you can imagine this, when I got ill I weighed 230lbs and within four months I weighed 110lbs, so I lost 120lbs, more than half my body. I had no muscles. That’s why I couldn’t walk, I couldn’t stand up. My legs would not hold me up. My bones, my arms were literally… I looked like a walking skeleton. When I was in the hospital, my son, Jon, who plays in my band now, he came to Omaha and he brought a Stratocaster. He said, ‘Dad, you need to keep playing. You need to keep in touch with who you are.’

“So, they sat me in a chair, they carried me and they put the guitar in my lap and I did not have the strength to push the string down to the fret. I could not do it. I’m pushing and pushing and the string wouldn’t move. I said, ‘Take the guitar out, I can’t look at it.’ It was a sad day. I lost it after that. Part of relearning to play was building up strength again.

“Also, as the strength started coming back, because I was getting physical therapy every day, I was working with weights, I was doing all this, but the signals from my brain to my fingers were not there either, so I had to get that back.

“Even when I was getting the strength I’d say, ‘Okay, I’m going to try a barre chord,’ and I’d put one finger here and I’d put this finger there and then I’d press and see if I could get it to play. It took a lot of work. I mean, I still had it up here. I knew where the notes were. I knew where to put my fingers to play an A chord, but to actually make it happen was a whole other thing.”

How did the difficult road to recovery change the relationship you had with the guitar?

“Well, I basically practised on an acoustic, because it’s a little more difficult. It didn’t have little skinny strings and I figured that would help build the strength quicker. The first few times I tried it, the pain in my fingers was excruciating. It reminded me of being 10 years old and picking up a guitar for the first time and trying to play and having no calluses.

You get to where your fingers bleed and then you cover them over with Krazy Glue and you keep going

“I remember saying to my wife, ‘This is the most painful thing I’ve ever tried to do. How did I ever do this?’ She said to me, ‘Well, you actually did that, so just keep going.’ I know it’s a cliché, but it’s the truth. You get to where your fingers bleed and then you cover them over with Krazy Glue and you keep going.

“A funny story, a tabloid in America, or television show, did this thing about John Mayer and they said, ‘We have to say something that we’ve learned about John Mayer. On his contract rider he wants Krazy Glue.’ They go, ‘What’s he doing with the glue?’ and they’re implying he’s sniffing it.

“They say, ‘He’s told us he puts it on his fingers,’ and they all go, ‘Ha, ha, ha.’ I’m like, ‘Well, yes. I don’t know a guitar player who doesn’t have a tube of Krazy Glue. I’ve got one in my guitar case.’ It’s when your fingers start to crack, you glue them together and you keep going.”

Your fans actually crowdfunded the liver transplant that saved your life. That’s pretty incredible…

“Well, without them I wouldn’t have gotten the operation or maybe I could have sold my house and moved my family into a little trailer in Garden Grove or something… The American healthcare system is for profit. We’re the last civilised country on the face of the earth where healthcare is for profit and when somebody sees a sick person, they see a way to make money.

“But the fans, I’m in their debt and my gratitude is huge for them. What my wife always says is, ‘All those people bought stock in your liver. The way you pay the dividends on the stock is you better go out there and play your ass off, because that’s what they want. That’s why they did it’. Those fans want to still be able to come and see me play and I had better play for them and not bullshit them. So, I better mean it when I play.”

You’ve worked with Lance Lopez before. How do you rate him as a player?

“Lance is a great man. He’s an incredible guitar player. I mean, he’s intimidating at times on the guitar, because he’s got so much technique and so much passion. He has a lot to say. He’s been down the road I’ve been down - going through some severe addictions and actually examining himself, looking in the mirror and saying, ‘This is not what I want out of life,’ and then changing his life and getting serious about being alive and about being a musician and having a good life. Then he falls in love and now he’s a father. He has all this to say in his music.

To me, when I put music on, I want it to immediately affect me emotionally. I’m not looking to be impressed. I’m looking to be moved

“There are certain young players out there who are very proficient and very technically gifted, but I feel like they don’t have enough life experience to put authority into their music. When Lance plays, he’s making a statement. He’s a great player. We did one gig with The Blues Machine already in Holland and I watched Lance front that band. I watched him command a room with 10,000 people in it. He’s one of the greats, I think. I think he has a huge future. He’s just really getting going.”

Do you think life experience is important to play blues well?

“Yeah, it is to me. It doesn’t have to be to everybody - there are plenty of people out there who just want to go and hear a guy and they want to be really impressed with his technical wonder. For me, I want to hear something that has substance to it and that has something to say. That’s why, for instance - and, again, it’s a cliché - but BB King could play one note and rip your guts out. That doesn’t mean you have to do it with one note. You can rip people’s guts out with one note or 10,000 notes - there are no rules here, I don’t think. But I like the authority and the statements that guys can make musically when they have a lot to put into it.”

What do you think the essence of all the best blues guitar playing is? When do you feel you’ve done a good job?

“To me, when I put music on, I want it to immediately affect me emotionally. I’m not looking to be impressed. I’m looking to be moved. I mean like Blind Willie Johnson, Dark Was The Night, Cold Was The Ground, put that on. If you’re not a mess of quivering jelly at the end of that song, there’s something wrong. He’s not a technical wizard, but there is so much soul and heart and feeling and life expression in there.

“To me, I think the reason that any sort of art was invented, was thought up, came into being, was people trying to express something they could not express in words, trying to express feelings and emotions and beliefs. In the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, when you walk in there’s a big quote on the wall from Vincent Van Gogh as to why he became a painter. It says, ‘To express a sincere human emotion.’ That’s what I look for in music. That’s what I look for in art. That’s what I look for in drama or movies, but that’s just me, as I say.

The guitar was taken from me and given back to me and I want to keep going as long as I can

“There’s room for everything, but I have a certain thing I look for and that is some sort of - this is going to be a little cosmic here - but I’m looking for something that is attempting to express some sort of human universal truth, maybe not always being able to do that, but the attempt to express that is what I’m interested in. Sorry, that was a really longwinded answer to your question…”

That’s a good answer!

“I’ve just had two double espressos, so I’m going here.”

What’s next for you and guitar?

“Man, it was taken from me and given back to me and I want to keep going as long as I can. I want to give it my best attempt at expressing that truth. I want to do that as long as I can, it’s the thing that gave me purpose when I was a kid, and it still does.

“Now, I have a wife and children and they give me the ultimate purpose in my life, but without the music, I wouldn’t be me. That’s what my wife knew. That’s why she pushed when I got back and I said, ‘This hurts. I can’t do this,’ and she said, ‘No, you can do this.’ She’d say, ‘Come here and watch this video of yourself. You used to do this. That’s you, it’s not the guy sitting on the couch who can’t walk and is trying to relearn how to speak and shit.’ She said, ‘That’s your essence. You’re a musician, work at it, get it back.’ It’s back and I want to enjoy it. I want to try to communicate with people and I want to try to connect with people.”

Walter Trout guests on the track Can’t Take It No More from Supersonic Blues Machine’s album, West Of Flushing, South Of Frisco

Don't Miss

Billy Gibbons picks his standout moments from a 47-year career with ZZ Top

Robben Ford talks Butterfield, blues and breaking in SGs

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.