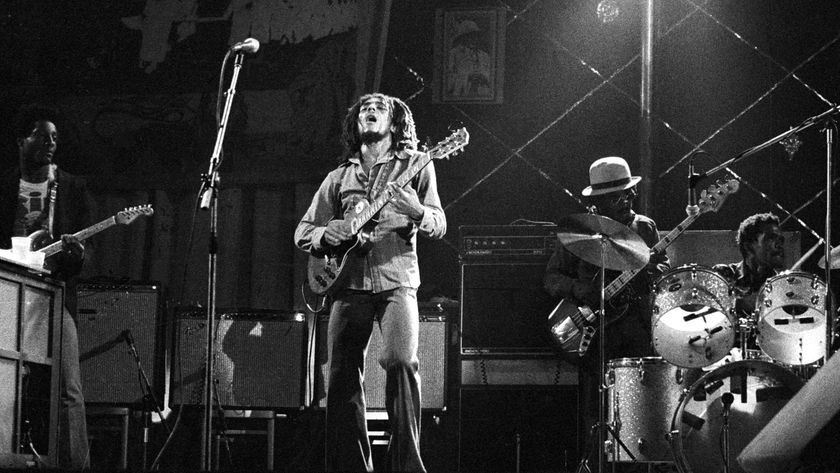

Billy Corgan (center) and Geddy Lee (right), seen here with Lee's Rush co-hort Alex Lifeson, talk about pushing and transcending their bands' sounds in an interview with MusicRadar. © RD / Scott Kirkland / Retna Di/Retna Ltd./Corbis

If we are to believe the words of Ecclesiastes that "there is no new thing under the sun," then there would be little point to making music in 2012. But Geddy Lee and Billy Corgan continue to disprove this theory with their respective bands, Rush and The Smashing Pumpkins, forging bold and brilliant musical paths on the just-released albums, Clockwork Angels and Oceania.

Part one of our exclusive Billy Corgan and Geddy Lee interview

Geddy Lee on his five favourite bassists

In Part One of our extensive interview, the two posited, in eloquent and passionate terms, that music as an art form is worthy of meaningful, sustained examination. And in Part Two, presented here, they continue their dialogue forcefully, thoughtfully and with good humor.

Let's talk about the sonic choices you have to make these days when recording an album, and really this goes into the mastering. Both of your albums have great dynamic range, something that is missing from a lot of music now that people are mastering for digital downloads.

Geddy Lee: "Yeah, mastering is a dangerous thing. You know, you go through the history of music, and mastering was a supposed to be a way to get your music onto vinyl without [the needle] skipping. And then the role of the mastering engineer took on such a distorted sense of importance. As music turned to digital and suddenly you had the possibility to make things louder than loudest, which boggles the mind but it's true, and what you have are all kinds of different ways of distorting your music.

"Then it becomes a game of 'this person's record is this loud,' so how can I possibly produce a record that is not that loud and actually has dynamics? It's a fight. It's a battle between record company, between producer and between mastering engineer. Because the louder you make your record in a digital process, the more dynamics are squished out of it. Nobody knows exactly what happens, but the dynamics in the performance disappear, and everything is at the same volume.

"With us, it's always a matter of compromise. We say, 'Yeah, you can make it loud, but at the point where I feel the dynamics are going away, then stop. Stop making it loud.' [laughs] But you know, it's a strange, strange part of the process now."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

Billy Corgan: "I pretty much echo everything he says. Luckily, we've been working with Bob Ludwig lately, and he's got that kind of understanding of how to bring it to the modern era without compromising the values. It's pretty amazing when you can sit with somebody like Bob and talk about Led Zeppelin, because he mastered those records. He talks about the choices he made back then and the choices he has to make now, and sort of the 'linearity,' if that's even a word, of his thinking as time has progressed.

"It got pretty weird there, particularly in alternative music in the late '90s, because all of a sudden everybody's doing this brick wall mastering, and every band sounded like, you know, God came down and started a band. [Lee laughs] Suddenly, organically produced force didn't sound as forceful anymore."

Lee: "That's right."

Corgan: "It's kind of weird because obviously both of us have spent a lot of time figuring out how to create that force, and then play off that force by coming down and creating interludes and things like that. Suddenly, when you have somebody that just wipes you out and you see the audience responding to this insane… I don't even know - battering [laughs], you know, if you oversquash yourself, well, there goes why everybody likes your band. It's kind of a weird place to be put in."

Lee brings his message to the people with Rush in Concord, California, 2011. © Tim Mosenfelder/Corbis

Lee: "It makes your music relentless. With a band like us, we're relentless enough. [laughs] We need to relent sometimes." [everybody laughs]

Corgan: "Relent and repent!"

Let me bring up the dreaded "c" word: concept album. Both of your albums are concept pieces, but in vastly different ways. Geddy, Clockwork Angels is a self-contained concept, and Billy, Oceania is part of a bigger work - Teargarden By Kaleidyscope. How much do you let the story or the theme guide the music?

Lee: "In my case - in our case, as Rush - it was walking a fine line and using the story to propel the music, and using the settings of the story to create evocative musical atmosphere, as opposed to letting the story dominate the music. That is a trick, and it is difficult, and it comes with failure, and having done a number of concepts in the past and learning when you become a slave to the story and a slave to the lyric, and the music loses some life of its own.

"And so, for me, it's a balancing act, and it requires a lot of discussion between the lyricist, Neil, and myself as a singer, and Alex as my co-musical writer. It's just keeping a watchful eye that the songs have a life and a purpose as an independent spirit, as opposed to only in the context of the song before and after it. You want to be a link in the chain that's the concept, but you don't want the chain to be so weak on its own that it doesn't have a statement that it's making unto itself."

Corgan: "I've definitely been guilty of letting conceptual issues weigh me down, and to echo what Geddy said, I think I've learned where you can kind of go too far. Where I'm at now with Oceania, I worked off sort of a set of general themes, which kind of keeps me in a certain part of the universe… and will drop certain symbols and certain musical feelings, 'cause I can get too vague at times for me…

"To answer your question, the longer range purpose of starting the Teargarden project was to document… I don't know what the right word is - 'rejuvenation' sounds like a bad New Age word… The Smashing Pumpkins as an idea had sort of exhausted itself, and there I was with a 19-year-old drummer and no band to speak of. I wanted to document that journey publicly, if I could actually reclaim what I felt I'd lost in the process of the Icarus getting too close to the sun kind of stuff.

"Could I, in essence, either exorcise the ghosts of the past or would I succumb to them? I was willing to take that in a very public way. Maybe I've seen too many European art films - it felt almost very cinema verite. So I started from a very simple and fundamental root and was immediately attacked by my fans for putting out lesser work, and was basically declared DOA. It's not that I needed to fail to feel that. I needed to find some musical joy again… and go back to trusting myself.

"The Pumpkins are very kind of publicly involved, basically since '95 - the internet's been part of the process. So, the funny thing is, and here's where I do have to give fans credit, over the 10 or 12 Teargarden songs that were released, I felt like we were kind of dialing it in; we hadn't felt, like, let's call it 'the hot spot.' But our fans, the ones that really pay attention, started pulling me aside about a year ago and they said, 'We know you're on to something.'

"And it was a really good feeling, because I felt like somebody's listening. They can actually see through the crap here and see that I'm dialing something back in that you can't mess with. Having been through that before, and I respect this in any other band that finds that, it's so hard to get on that roll. But once you do, it seems as if things just flow out of you, and then one day maybe it isn't there like it was and you have to find a new game…

"Teargarden is just a way to document that process, and then of course, it brings up these other themes that come up, which is getting older, what is a band? - I get this: 'Why call it Smashing Pumpkins?' You know, like, 'Why continue even under the name? What does it mean?' I'm inviting all of these questions - it's almost like a public exercise."

Corgan shreds during a Smashing Pumpkins show in Lisbon, Portugal, 2012. © JOSE SENA GOULAO/epa/Corbis

I'd like to get your guys' thoughts on the element of jamming. How important was jamming during the making of your new albums?

Lee: "I think jamming is the way we begin to communicate. In the old days, people actually wrote notes on paper and sent them to each other. [laughs] I guess that's how they jammed. For us, growing up in a kind of illiterate musical microcosm, that's how we start our musical conversation - so it's essential. The jam becomes the way you begin the conversation, and then ideas start to spring forward and you have something to talk about.

"It's very rare - and it does happen on occasion - where I'll take a piece of lyric and I'll just sit down and purposefully craft that melody around that lyric because I think the lyric is the wellspring for the song, without question. But writing music in general, it always begins with jamming for me in our little world. Having worked so rarely with outside musicians, I don't know how it happens for others, but I'd suspect that it's some sort of jam that starts the whole thing."

Billy, what about you?

Corgan: "I don't know. The two key versions of the Pumpkins were never really jam bands. I think where both versions of my bands have been successful have been sort of being able to rummage around let's call it 'templates.' And I'm listening, and I'm picking up directions and vibrations, and then I have to quote-unquote write them into parts. I've never had a situation where it kind of falls together, but we do set up improvisation forms, and then through that everybody can express themselves. It may be a little different than jamming; it may be a little like an improv crew that has cues, and then off the cues we switch.

"We used to play, back in the day, a 45-minute song that had seven cues, and every section was improvised."

Lee: "Cool."

Corgan: [laughs] "Yeah, well, when the arena was half-full. [everybody laughs] And I would be railing against the people that left."

Lee: "But that's very jazz, though, right? What you're talking about…"

"Jamming is the way we begin to communicate," says Lee, pictured on stage with Alex Lifeson. © Brittany Somerset/Corbis

Corgan: "Yeah. Maybe I've idealized jamming, but I've never been in a situation where I can just play my part, and everybody just plays their part, and I go, 'Wow, that's great as it is.' I've always felt like I had to go back and re-organize the raw data."

Lee: "Oh, sure. That's what I'm talking about, as well. Very rarely do we do jams that are finished things."

Corgan: "Yeah, but I've idealized your band so much, I just think things come out of you like that." [everybody laughs]

Both bands have a very recognizable sound, but it's one that can mutate. On the new albums, how do you feel you explored and pushed the sound, and maybe even transcended it?

Corgan: "What I was trying to do was get to a place where I was organically producing music not in a reflective place of sentimentality. When we talked before, with the song Inkless, which I almost didn't put on the album because it was sort of familiar Smashing Pumpkins territory - but I know that that came out of me organically, so I was OK with it. But if I felt like, Oh, I've got to do this 'cause it's what people expect, that's where I draw the line.

"And I'm sure Geddy knows what I'm talking about. It's like sometimes stuff just comes out of you because it's sort of your thing."

Lee: "That's right. It's called 'style.'"

Corgan: "Yeah, it feels good. It's like, 'OK, this is my thing. This is the way we do this, or the way I do it.' I wanted to escape the consciousness where I was so aware of what the expectations were that either my mind kept rejecting things that were familiar just out of hand, even if it was stupid to do so - a good riff or a good idea - or what's even worse is me reacting against it and feeling that I have to go in a different direction, away from what I'm comfortable with - my own style.

"I've had to kind of learn on the pro and the anti, and I've spent a lot of time on the anti, to where now that I came back to a comfortable spot - I think that's why Oceania has a nice balance, because people say, 'It doesn't sort of sit anywhere.' And I'm like, 'Exactly.'

"I'm sort of in a place where I don't need to avoid the past. If this makes any sense, there's a Buddhistic idea, and I'm sure I'll get killed by somebody for saying it wrong. There's like the four tenets of Buddhism, which are like, 'You must completely care, you must not care, you must understand why you need to care and you must understand why you need not to care.'"

Corgan: "I'm sort of in a place where I don't need to avoid the past." © JOSE SENA GOULAO/epa/Corbis

Lee: "Well, I understand exactly what Billy is talking about. For years, we did the same thing in that anything that smelled of the past, in the smallest and most minute way, we avoided - regardless of whether we needed to avoid it, or if it should be avoided. Or, as he put it, whether it was a good idea. [laughs]

"I think then you get to a point where you're comfortable with your own sense of yourself. In our case, we've got such a catalogue of ideas that it's hard not to run over ourselves. For me, we're in a place now where we'll find ourselves mimicking ourselves in a way, and doing that in a kind of intentional way, but tongue in cheek - it has to have a purpose.

"For example, there's a song on the album called Headlong Flight, and when Alex and I started jamming we realized that we had written this bit that sounded really similar to the opening of a song called Bastille Day that we wrote many years ago. You know, we kind of laughed about it and didn't pay too much attention to it, and we created this long instrumental piece that kind of had a silly name, and we were just going to leave it at that.

"But when the lyric came along and we realized that this was a song at a point in the story where our hero is looking back on his life, reminiscing about the good and the bad, and regardless, he still wishes he could do it all again, I realized there was a real opportunity to use that bit of our past as a kind of Bastille Day Redux."

"So we had fun with it, and it suited the story, you know, so I don't worry so much about whether I'm treading on ground that I tread on 30 years ago. It depends on the panache with which I deliver it. I'm bringing a whole 30 years of experience to that kind of idea, and I know that I'm not going to settle for just a rehash of some old idea. It's got to bring something fresh to the end result, and it's got to be transformed by that new context."

Corgan: "Beautifully said."

In talking about sound, I have to point out that there something that both bands very much have in common: nobody can sing like either of you. Nobody sings like Geddy Lee, and nobody sings like Billy Corgan.

Lee: "Nobody wants to sing like me!" [everybody laughs]

But that's what makes you guys interesting - in both cases.

Lee: "Well, thank goodness for that."

Lee plays with Rush at Madison Square Garden, New York City, 2011. © Brittany Somerset/Corbis

Corgan: "I used to think that my voice was my biggest curse, because it's kind of like a wild pony, the thing, you know? But now that I look back, I'm really humbled because it's the thing that… it's served me well, let's put it that way. It's helped identify and unify my music. It's given me a whole host of opportunities that maybe if I had a voice like somebody else, I wouldn't have had. I wish I could sing as high as Geddy."

Lee: [laughs] "So do I."

Corgan: [laughs] "Geddy wishes he could sing as high as Geddy. We call it like the 'Bono note.' All the great singers can hit that super - I don't know if it's an A or a B, 'cause most bands play in E, so you have to be able to hit one of those super-high notes to make the epic moment, and I've never been able to hit that note. So I tip my cap to any of the great singers who can hit the dude note up there."

Lee: "I started out with a fairly coarse version of my heroes, like, Steve Marriot and Robert Plant, and I felt like I was a squeakier version of those guys. I've spent my life learning how to use my voice and learning how to mature my voice, and a lot of it has to do with being open and working with different producers, and having them help teach you how to sing in a different way and treat the lyrics in a different way. A lot of it has to do with just being open, being open to allow your voice to evolve, and taking chances, and taking care of the instrument."

Corgan: "That's true, too."

Lee: "It's a difficult thing. It's a really difficult thing, and when I go on tour, I think about… if I didn't have to sing, man, this gig would be soooo easy!" [everybody laughs]

Corgan: "I think the same damn thing! I'm so jealous of my bandmates."

Lee: "Yeah, man. They're just playing. Singers don't play, they sing. That's work. That's the same as working really hard. And it's the instrument that's most susceptible to environmental conditions. Like a drummer's musculature, those are the two toughest gigs on tour, I think. Anyway, I'm lucky that I've been around long enough to have enough opportunities to mature my voice and to work on my singing, because when it's right, it's a fantastic feeling."

Geddy, you guys recorded Clockwork Angels in a new way, having Neil play to music fairly spontaneously without writing his parts out. Was that nerve rattling, or was it fun in a tightrope-walking sort of way?

Lee: "Well, I'm sure it was nerve rattling for him. It was fun for us to watch. [laughs] And it was fun for Nick [Raskulinecz], our producer, because he felt like 'Top of the world, Ma! I'm telling Neil Peart how to play.' It was great for [Neil]. It was really great for him, because he's such a deep musician. His ability is boundless. I've never met a guy like that."

Corgan with fellow Pumpkins (from left) Nicole Fiorentino, Mike Byrne and Jeff Schroeder. © Paul Elledge

"And he's also fearless in that way that, if you give him a context where he can feel comfortable just reaching down and letting himself be spontaneous, and you see the result - I think his drum tracks sound fresh and alive, and they propel the band in a way that hasn't happened in quite some time. I think it really only happens like that live. That was such a huge step for him. So I applaud his guts to allow himself to be put in that position."

Billy, was there a similar aspect to recording Oceania for you? I imagine it was quite different because you were working with a fairly new band still.

Corgan: "To reverse the mirror a little bit, in my case, Mike, when he joined me, he was 19 and was working at McDonald's. He'd never been in the studio and had never played in front of more than 50 people. So he has this incredible natural talent, blistering hand speed and a great natural groove. He's like Kenny Aronoff level with a natural meter - it's kind of crazy. We don't even need to use click tracks with him because he's a natural, consistent player.

Lee: "Wow, that's great."

Corgan: "It's crazy! So you look at somebody with a natural gift and you're like, 'Where did this come from?' So you take this 19-year-old kid, and you start trying to build up his mind into how to approach his drums from a writing standpoint and a support standpoint when he doesn't have any of those contexts. At the same time, you want him to bring his own voice to the table because he's bringing a fresh set of influences which only somebody in their teens or 20s can bring. He's listening to all these bands that I'm never going to listen to. We laugh and call them the 'bear' bands - 'bear this' and 'All The Bear,' they all have bear names, I don't know. [Lee laughs]

"We've been on this journey together, and on Oceania there's these moments where's he's scratching his head; he doesn't really understand what I'm looking for 'cause he's playing his ass off. At that point, he hasn't turned the corner where he can hear the army of guitars that's going to go on top of it. He's reacting simply to the information he's been given. I'm sure it's similar with the Rush guys, you know, you're given some scratch tracks and you're playing along or whatever. It's certainly not how it's going to end up all finished and polished up.

"So it's hard sometimes. I was used to Jimmy Chamberlin, who had an intuitive gift at being able to hear that orchestra in his head as he played. So here's Mike, 21 years old, and I'm going, 'Come on, you've got to lift yourself up and sort of lean into the space and imagine what's going to be there.' He doesn't have that experience; he's got to kind of trust my word on it. And what's been nice, now that the record's done and people are reacting to it, and he's seeing how people are reacting to his drumming and his support of the music, he's come back to me and said, 'Now I'm beginning to really understand.' It's cool to watch him go through that process."

Lee: "That's a great experience for him, man. That's what it's all about."

Corgan: "And people get kind of crazy and try to compare him to Jimmy Chamberlin - you know, I started playing with him when he was in his mid-20s. So here's Mike, five years younger and at the start of this journey. And I've had to say to a few fans, 'Let the kid have his journey here.' You know, we could fake him into perfectness, but that's not what you really want. Let him have his journey, take the ride with him and watch him mature, and let him figure it out for himself."

Lee describes Rush drummer Neil Peart as "fearless." © Tim Mosenfelder/Corbis

"That becomes part of the story. We don't want to cover it up. That's the mentality of the modern world, like, 'Cover that stuff up. Hide it. Pro Tool it away.'"

Lee: "You lose the authenticity."

Corgan: "Right. That's what I'm saying. And look, maybe there's one song where it doesn't work as great as it would have if he did blah, blah, blah. But then there's that other moment where it works on a level that none of us can understand because it is that moment, you know, where it's fragile and it's insecure and it's not certain.

"There's something exciting about watching people evolve. Geddy, when you were talking about Neil doing these spontaneous takes, when that part gets taken out of the equation, then we're not musicians anymore. We're something else - we're politicians."

Lee: "Assembly line."

Corgan: "It's really strange for people who grew up loving music, in awe of music, to then have somebody in a suit later on go, 'Hey, get in line over here because we know what we're doing.' And what I've been saying in the music business, all behind close doors to these people, and I say it very forcefully, is 'If you knew what you were doing, A) I wouldn't be here in this meeting, and B) you would have the record sales that you think you should be having.'

"How come the album's been diminished in the culture? Artists have been diminished in this culture. It's been hollowed out by almost a political class in the music business - the suits have taken over and cookie-cuttered everything out. And now they're scrambling because their business is failing, and suddenly, people like us look really valuable because we know what we're doing. We've known what we're doing all along. Even when we don't know what we're doing, we know what we're doing because we trust music."

Lee: "And it's real, it's authentic. People, at the end of the day, want real things. You know, you can fool somebody for a while, but in the long run, human beings need to relate to things in a human way. They want the authenticity, and the authenticity, the genuine heart in music, will show through and be the appealing factor, sooner or later."

Corgan: "Amen."

Lee: "Can't stamp that out in music. Or any art. It's what makes any art enduring."

Part one of our exclusive Billy Corgan and Geddy Lee interview

Geddy Lee on his five favourite bassists

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

Most Popular