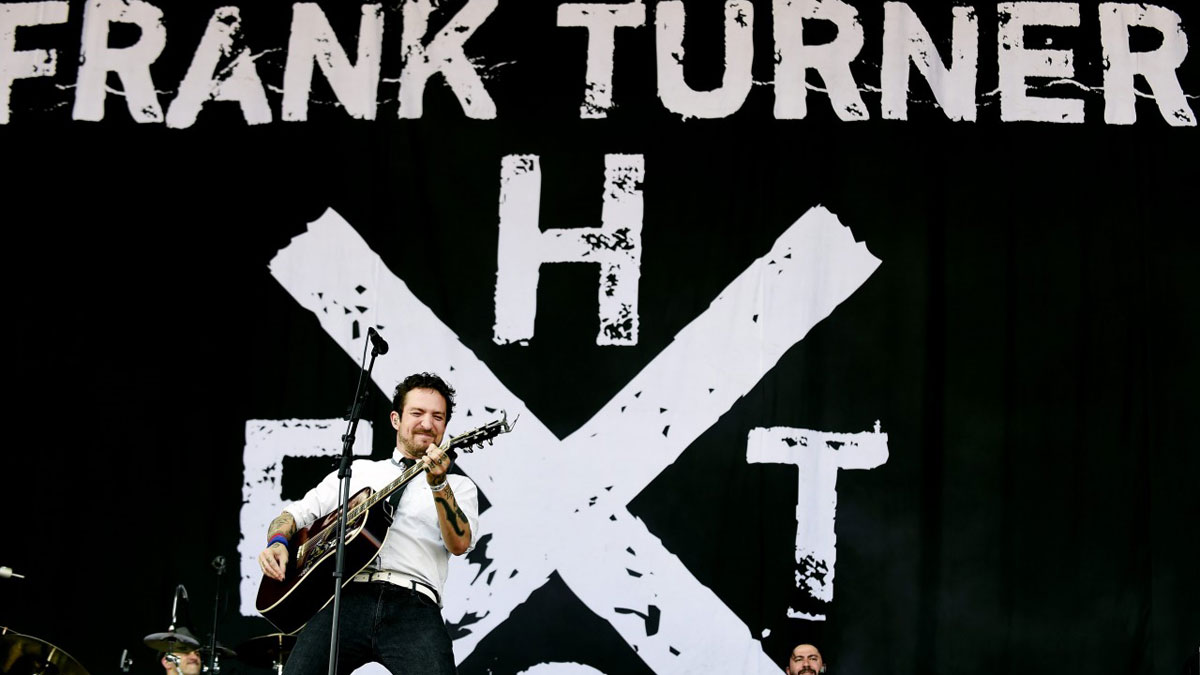

Frank Turner on his songwriting secrets

Early tracks, Elliot and going electric

Introduction

‘Open, honest, and direct in speech or writing’ - that’s our Frank down to a tee. In an intimate discussion about songwriting, we talk turkey with Turner…

We meet Frank Turner in the impressive surrounds of the Terrace Suite in London’s swanky Soho Hotel. This is par for the course with a certain level of star, but it’s encouraging to think that this one made it here off the back of his own writing.

The Hampshire troubadour’s sixth album, Positive Songs For Negative People, is his most gripping yet, so we grabbed two overstuffed armchairs and sat down for a typically unreserved discussion about his songwriting inspirations, the agonising early efforts he doesn’t want you to know about, and making the personal universal.

What’s the earliest song you remember writing?

I wasn’t really into music until I was about 10 and then it hit me like a tonne of bricks

“[Groans] I wasn’t really into music until I was about 10 and then it hit me like a tonne of bricks. I got into Iron Maiden, that was the first thing, and then Queen and Guns N’ Roses. Guns N’ Roses are now a band I loathe with every fibre of my being, but as a 10 year-old they were fine - which, for me, sums up what I think about Guns N’ Roses!

“It’s tragic to admit, but I thought Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door was a Guns N’ Roses song and that was the first song I learned on guitar. The verse was G, D, A minor and I remember playing G, D, A major, because I hadn’t learned A minor yet and then thinking to myself, ‘Hey, I just wrote a song!’”

Can you recall any of your early song titles?

My first band did record a demo once. But I’m going to kill everybody who owns a copy

“Oh god, yeah. The first band I was in was me and my two best friends as a teenager and we had one song that we were all really proud of because it had a riff, rather than just chords, which I realised many years after the fact that I’d sort of nicked from the Sugar Ray song, Mean Machine!

“The song was called Wonderful World and it was a terrible sort of sub-Sex Pistols dirge. We were into all that, and The Clash and Nirvana. We were also bang into stuff like Pantera and Megadeth, but there was no way on God’s green earth we could play anything like that, because we were completely shit… and 12!

“We did record a demo once, so that does exist somewhere. But I’m going to kill everybody who owns a copy.”

Picking up the positive

Have there been any recurring sources of inspiration for you?

“I’ve certainly over-used TS Elliot, I’ll fess up to that. It’s an addiction I’ve tried to get over, but certainly in the Million Dead days there were an awful lot of TS Elliot references going on and suddenly we had songs called Murder And Create and all of that kind of thing.

Tape Deck Heart was an attempt to write a break-up record from the perpetrator’s point of view. I feel there aren’t enough of those

“My bible of songwriting is the first three Counting Crows records. I strongly feel like everything I know about songwriting comes from those. Just in terms of songwriting as an art-form as distinct from musicianship - the business of constructing a song. Adam Duritz can reconstitute a third verse like no man alive. He doesn’t repeat himself. He uses his words efficiently and I find that very inspiring.”

One theme that’s obvious on this record regards maintaining a positive mentality. Why has that been so important?

“A lot of it was reacting against Tape Deck Heart, which was a record about fucking your life up, essentially. I was in a long-term serious relationship that I cared about and I fucked it up.

“In a way, it was an attempt to write a break-up record from the perpetrator’s point of view. I feel there aren’t enough of those. Most break-up records are like, ‘Woe is me! I was wronged!’ But it’s like, ‘Well, there’s a lot of people who did some wronging who aren’t writing records [about that] right now!’

“So Tape Deck Heart was cathartic and when that was done and dusted and I could write for this record, there was a sense of liberation in not having to write songs about being a shithead anymore. I felt like I should do something different. To look at things differently this time around.”

Electric feel

Distorted electric guitar seems to take a more prominent role on this record than it has before. Why is that?

“A big bugbear for this record for me was that I wanted to capture the feeling of a live show. The Sleeping Souls and I are, in my opinion, a fucking good live band, if I can say that without sounding like a dick, so I wanted to make sure that we got that on record this time.

It was liberating to be like, ‘I’m going to wail!’ Of course, I’m not - I can’t play a guitar solo to save my life

“I also wanted it to be quite an aggressive, in your face record. Tape Deck Heart was quite a slow burner, but I wanted this one to be more of a slap in the face than a, er, back rub!

“Then also, there are a lot of stylistic decisions on my early records, which in retrospect, were trying to distance myself from being in a hardcore band. I’m very proud of it, but I didn’t want to be ‘That guy who used to be Million Dead’ for the rest of my life.

“[This time] it was like, ‘Fuck it, I feel like playing electric guitar.’ It was quite liberating just to be like, ‘I’m going to wail man!’ Of course, I’m not - I can’t play a guitar solo to save my life.”

The integration of a band seems to have occurred very naturally for you. What’s the best way to manage a band built around a writer?

“Well, that’s a difficult question and one that we have spent many years argu… I mean, answering - Freudian slip there! [Laughs] But it’s true, it’s not settled and it’s not easy.

“Being in a room with creative people is always going to be quite fraught. We’ll have sound checks where [we’re arranging songs and] people storm off and go and sit in a room in a mood with each other.

“But then there’s that wonderful moment when the record is done where you can just have your sound check and just play some songs and no one’s trying to kill anyone else. It’s a relief. But I take my hat off to the guys in the band because they’re fucking brilliant at what they do and I couldn’t do what I do without them.”

Bringing in the band

What’s the secret to making that dynamic work, in terms of the sound?

“I think we’ve all got quite good at thinking of arrangement as an art, as a separate thing to songwriting. With quite a lot of songs on the new record, we’d come up with an arrangement and then park it, and then say, ‘Right, imagine it was five years later. How would we do that?’ Sometimes it would be disastrous and sometimes we found the soul of the song.

I’ll take a Gibson over a Fender most of the time. I like the meatier vibe of those guitars

“Next Storm was originally brushes on the drums and fingerpicked guitar - almost a Crowded House vibe - then we said, ‘Let’s try playing like Thin Lizzy and see what happens’ and within three run-throughs we had the version that’s on the record.

“Another interesting thing we did [ahead of] this record was to build a stage audio monitor rig, so we had a digital monitor desk and all the same equipment every day on tour, which meant that in sound check we’ve got two and a half hours of playing time, so that’s where we did a lot of the record [demos], through the Behringer X32.”

What electric gear were you using?

“[Producer] Butch Walker’s approach is extremely, er, reductionist, so we got half of the record done in the time it’s taken us to get a kick drum sound on some of the records I’ve worked on. We loaded in and set up our live gear and, with the guitar stuff, I remember it was an old Fender Twin, or Deluxe, with an SM57 jammed into the speaker and the direction, ‘Now don’t play badly!’

“Ben uses his Fender Teles and I got given an extremely nice guitar from Gibson, one of the new ES Les Pauls, the hollowbodies, and, fucking hell, that’s a piece of wood. I used a Deusenberg as well, which was a new thing for me, but Butch is really into them. They’re so fucking good - really, really lovely guitars.

“I’m not the biggest tone nerd in the world. Personally I prefer chunkier sounds. I’ll take a Gibson over a Fender most of the time. I like the meatier vibe of those guitars, like a nice old SG or Les Paul.”

Making connections

And what were your main acoustics?

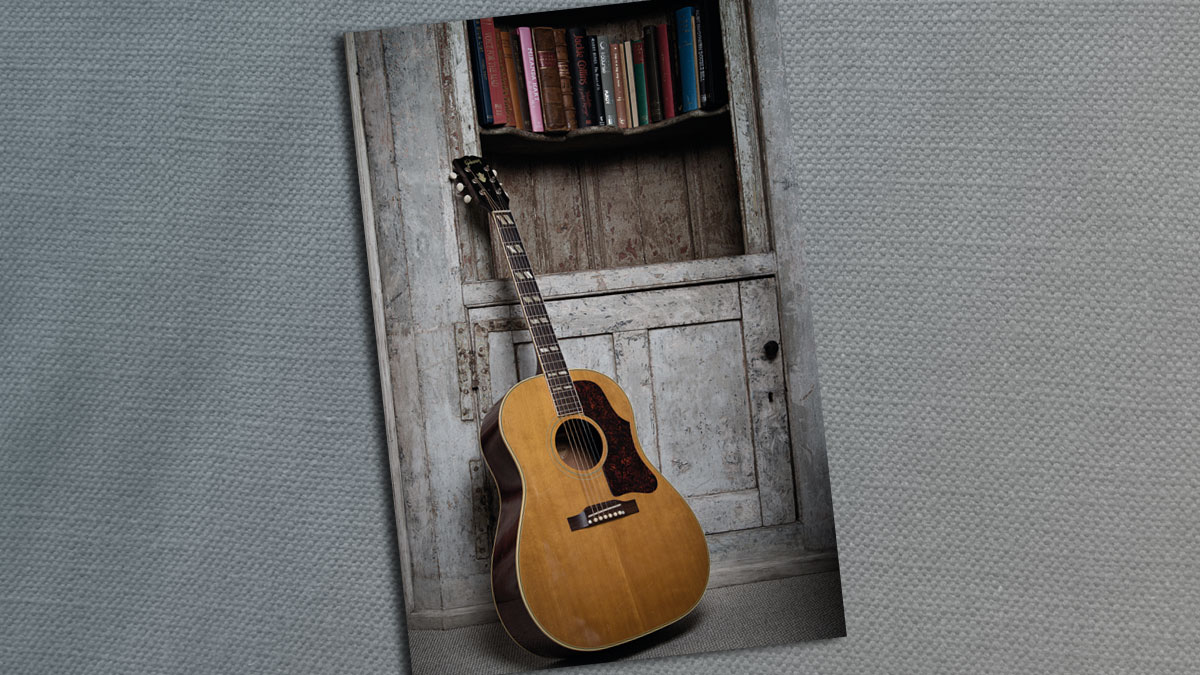

“I was mostly using a Gibson Hummingbird, which is my axe of choice. Again, I like acoustic sounds that are very full. I like an acoustic guitar that can equally attack a full range, across the spectrum.

“For a lot of bands, an acoustic is an accoutrement of an instrument, but given the centrality of the sound to what I do, that’s not what I want. I like an acoustic that has a fat bottom-end to it and really carries some weight.

You need something that feels personal on a universal scale. It’s almost like you’re pulling focus

“We had a couple of other bits and bobs - an old 1920s Gibson, one of the ones with ‘The Gibson’ written on it, which was on The Angel Islington, the fi rst track on the record - but it was mainly Hummingbirds.”

At it’s core, songwriting’s really all about connection. What do you think makes people connect with your music?

“Well, I think I’m the wrong person to answer that question. In fact, I try not to think about the answer to that question. Partly because it’s so enormously up-your-own-arse to wander through life pondering it, but also because I think that I would worry about breaking whatever it is about the process that’s working. It might terrify me into silence.

“I’ve traced this sentiment back, I used to think it was John K Samson [of The Weakerthans], then somebody else, then somebody told me it was Goethe. Obviously this isn’t the exact line, but he said, ‘The knack to great writing is to say something that’s personal to everybody.’ You need something that feels personal on a universal scale. It’s almost like you’re pulling focus. But, like I say, I would ask you!”

Matt is a freelance journalist who has spent the last decade interviewing musicians for the likes of Total Guitar, Guitarist, Guitar World, MusicRadar, NME.com, DJ Mag and Electronic Sound. In 2020, he launched CreativeMoney.co.uk, which aims to share the ideas that make creative lifestyles more sustainable. He plays guitar, but should not be allowed near your delay pedals.

“It’s about delivering the most in-demand mods straight from the factory”: Fender hot-rods itself as the Player II Modified Series rolls out the upgrades – and it got IDLES to demo them

“This time it’s all about creativity… Go crazy. Do whatever you wanna do with it”: Budding luthiers, assemble! Harley Benton’s DIY Kit Challenge is now open and there are prizes to be won

“It’s about delivering the most in-demand mods straight from the factory”: Fender hot-rods itself as the Player II Modified Series rolls out the upgrades – and it got IDLES to demo them

“This time it’s all about creativity… Go crazy. Do whatever you wanna do with it”: Budding luthiers, assemble! Harley Benton’s DIY Kit Challenge is now open and there are prizes to be won