Dierks Bentley talks production, personal songwriting and his new album, Riser

"I don't wanna seek out a certain sound that's already been heard"

Dierks Bentley talks production, personal songwriting and his new album, Riser

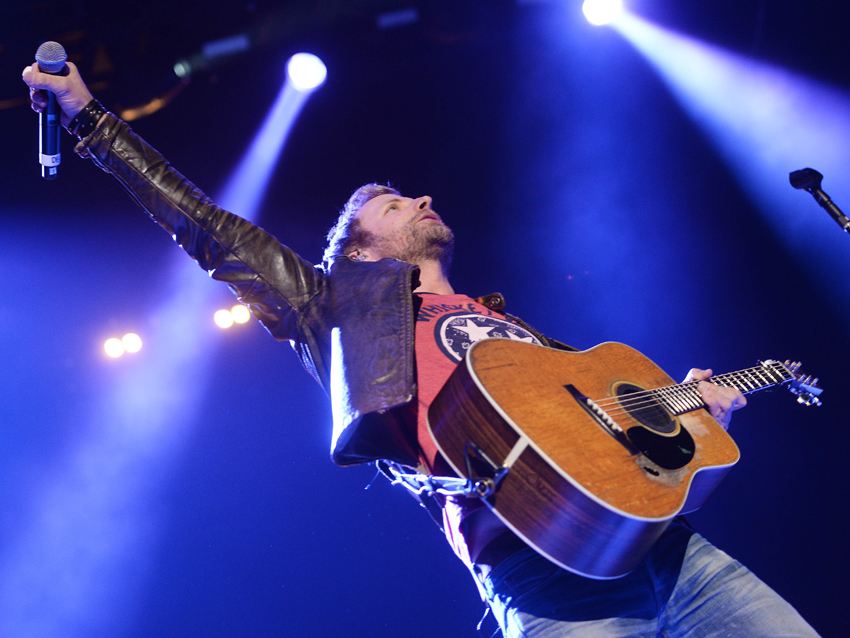

During the title track of his seventh album, Dierks Bentley drives home the idea that he’s a riser – as in, someone who rises to the occasion, rises above the fray, is perpetually on the rise. You get the idea. Metaphors aside, there’s measurable upward momentum behind the Arizona-born singer and songwriter, on the charts, where Riser debuted atop Billboard’s Country Albums Chart (the song I Hold On just hit number one on the Country Airplay chart), and on the road, where he’s recently become a bona fide arena headliner.

While making his decade-long professional climb, Bentley was also starting a family. A televised documentary sharing the same title as his latest album shows him and his band members stopping on the side of the road to celebrate his tour coach odometer crossing the one million mark. In another scene, you see him personally piloting his tiny airplane back to Nashville, where his pregnant wife and two daughters are waiting to meet him at the airstrip. All of that’s to say, from the career front to the home front, the guy’s got a lot going on.

Bentley talks openly about that tug-of-war in a new song, Damn These Dreams. And when he sat down with MusicRadar in his manager’s office, his dog Jake by his side, he also had plenty to say about the emotional range he covers in the set of songs and sounds he’s just released, why he’s sworn off vocal booths and how he’s inadvertently fooled people into thinking he plays an antique guitar. (You can purchase Dierks Bentley's Riser at his official website. For tour dates, visit his tour page.)

How did your wife and daughters respond to Damn These Dreams? It addresses how wrenching it is to be both a hard-touring musician and a family man.

“I think at first we all thought it was too personal. The only reason it made the record is ‘cause my drummer was so adamant about it when he heard it. He’s like, ‘That’s the most you song I’ve ever heard. You have to put that on there.’

“My songwriting, at its best, is like I Hold On, where I get these personal vignettes in the verses, and then the choruses are universal – everyone can latch onto… As I’ve worked at my craft of songwriting, that’s where I’ve tried to steer them towards, these little things, universal chorus, surprise at the end – make it a love song about your wife.

“Damn These Dreams is just, like, me and [co-writers] Ross [Copperman] and Jaren [Johnston] talking about love of music, love of family and how they just don’t fit together at all… I like having it on there, because it’s just really honest, and I think that in the end, that’s all that you can really go for, all I can really go for. Some people try to push the boundaries sound-wise. For me, pushing the boundaries in this was to go as personal as possible, because that’s where I am in my life right now… I know there’s a lot of dudes that can relate to this. Having kids and being a traveling salesman is pretty much what I do, which is what a lot of people do. You know?

“We put Bourbon [in Kentucky] out first, which I really wanted as a single, because I knew it was going to push the boundaries, as far as country radio and some of the happier, fun songs out there. It’s a real brooding song, and it pushed it a little too far, and we had to retreat [chuckles]. But it moved the whole album back, which was great, because I was able to go record some songs that reflected really who I am on the road. All summer long, I co-headlined a tour with Miranda Lambert, the Locked and Loaded tour. So much fun. That’s a big part of who I am: I love being on stage. I’m a happy person. I love getting fans off. Sounds Of Summer wouldn’t have been on the record if it wasn’t for that delay.”

Throwing listeners for a curve

So you added songs after testing the waters at country radio with Bourbon In Kentucky.

“Yeah. Back Porch wouldn’t have been [on album], and Drunk On A Plane might not have been… They provide a nice little pressure relief from some of the more life-driven songs.”

Did Sounds Of Summer and Back Porch bump other material from the original tracklist?

“There’s a song called Summer On Fire, which is another kind of kickass summertime song. Sound Of Summer kinda replaced that. I just dug the groove. I know it’s not saying anything new, but the guys that wrote it, I just think they did a good job at capturing what summer feels like to me – being out there on the bus and seeing America drive by, small towns, tractors, coolers in trucks and the tailgate scene. I just like the way it feels.

“It’s hard listening to a song like Here On Earth, or even Riser, when… you don’t give the listener a release afterwards. It’s hard for me not to sequence the record in a way that mimics the live show: ‘OK, you’ve gone through Here On Earth. Here is Drunk On A Plane. Throw the listener a bone.”

Pretty Girls is another drinking song on there, but it’s got more insecurity than swagger to it, because of the minor key and the fact that the guys never actually get up the gumption to make a move.

“The songs I really love have that tension, whether it’s lyrically just between the verses and the choruses, or between the lyrics and the music. There has to be some sort of tension. What’s great about that song is, you see the title Pretty Girls (Drinkin’ Tall Boys): ‘Oh, we know exactly what this is going to be about.’ And it’s really this groovier, darker ‘There’s just nothing to do in this town’ kind of thing. It’s not like everyone’s up on tailgates partying.”

On working with producer Ross Copperman

Growing up, you were a hair metal kid, who then discovered Hank Jr. There’s always been a certain rock attack to your music. On Riser, it’s very noticeable that the electric guitars aren’t heavily stacked and compressed. There’s also a lot of ambient steel, banjo, mandolin and effects. Where did this more brooding, spacious rock feel come from?

“I worked with a different producer and engineer, both of whom don’t come from a big country record-making background. I don’t think Ross [Copperman] has made a country record.”

He’s had country songwriting cuts.

“Yeah. He makes great demos. That’s how we’d worked together. I love his demos. They weren’t country; they were just good. And then [engineer] Reid [Shippen] is from the rock world, too. I’m definitely of a country mindset when it comes to production. But [with] those guys, the music was more about just amplifying the lyrics.

“A lot of times that means just staying away from the lyrics. There’s more ambient space on this than I’ve had at certain times. There were times when I was like, ‘There should be a fiddle fill. We’ve gotta fill that hole with something.’ They were like, ‘No. There’s no need. We’ll put a little sound in there to kind of bridge the two musical sections. But let’s not distract the listeners’ thoughts here by adding an unnecessary instrument.’ ‘OK. Never thought of it that way.’

“On Riser, we wanted to get the groove going on the second verse, but I don’t think we wanted to give away the four-on-the-floor kick drum thing yet. Reid was like [snaps fingers], ‘I’ve got an idea! Let’s break down half that kit. We’ll set up in this little room over here and just play like the Black Keys would play; just play kick drum and snare... It’ll sound different since it’s not the real room with the big overhead mics… We’ll get the groove started, but it won’t be the full sound yet.’ That’s a fuckin’ genius idea. Nothing I would’ve thought of before. So it’s kinda cool to work with some guys that come from a different background. They were using me to keep it in check, as far as keeping it country.

“I love ‘80s hair bands. I love those tones. But I don’t want to do anything that’s been done before. I mean, we’re all doing something that’s been done before. But I don’t wanna seek out a certain sound that’s already been heard. I just wanna do what comes naturally and blend a certain mix of musicians. Charlie Worsham and Bryan Sutton are arguably two of the greatest acoustic players in this town. Those guys have great record-making sensibilities, because they’ve worked on so many albums in this town. You mix them with players that come from more of a rock background. [Steel guitarist] Dan Dugmore has done it all. And [I had] a producer and engineer who can also play instruments and tweak stuff on their own.

“There’s a lot of, understandably, bitching and moaning about the loss of traditional country music, but I think one of the things people forget about with modern production is the possibility to get even more emotion out of a lyric. You see it with Ray Price – when those guys were cutting with the A-team session players back in the day, it’s really just a sound that was set in place… But you know, when the sound changes sometimes, you can use these instruments in ways that even get more out of the lyric, or do it in a more sparse, edgy way.”

Recording vocals

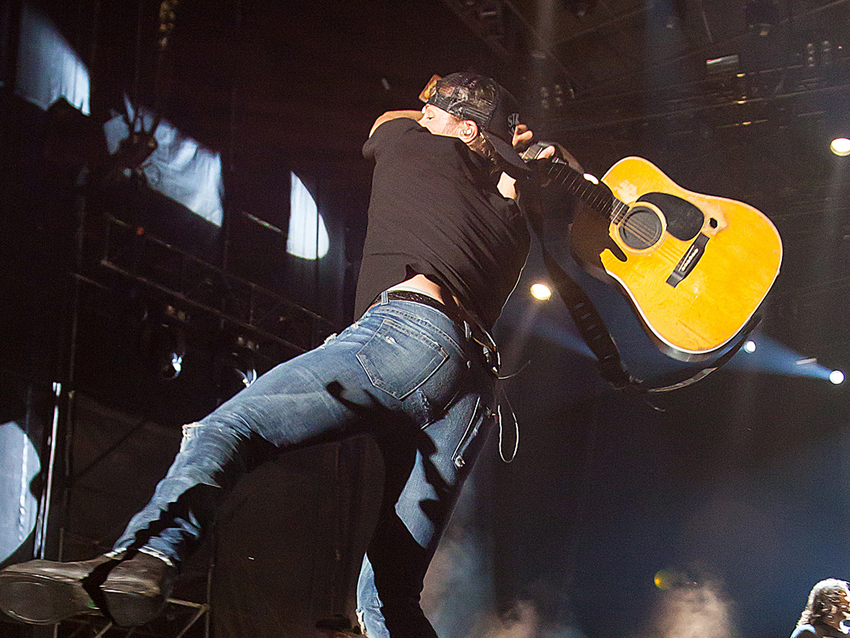

Above photo: On stage with guitarist Brian Layson, Ontario, Canada, August 2013.

Really, the one constant about the producers you’ve worked with is that they’re also your co-writers. That goes for Ross Copper, your longtime producer Brett Beavers, and Jon Randall, too. Any theories on why that keeps happening?

“The guys I work with tend to be songwriters. I guess it’s just the continuity that goes from when the pencil first hits the paper to when we start hitting the record button… I mean, Brett Beavers is such a good producer, and we’re such good friends. I feel like there’s a real healthiness to a relationship between an artist and a producer when you’re not dependent on each other, and you’re successful in doing things on your own without each other, because you can circle back around and say, ‘Here’s what I’ve been working on. I’ve got some new tricks. Let’s go at it again.’

"I know I’m gonna work with Jon Randall again. I know I’m gonna work with Brett Beavers again, and Luke Wooten… No one’s feelings get hurt, because I have such a great relationship with all the guys that I’ve worked with. It’s never ended on bad terms. I think it’s really healthy to not be overly dependent upon each other. You know what I mean? “

There’s a certain kind of vocal attack that works when you’re playing an arena. By necessity, you lose nuance, because you have to really project your voice to reach the people all the way in the back. But there’s an intimate quality to your singing on Riser, more so than on any of your other recordings. What made the difference?

“I’ll never do my vocals in a booth ever again – like, a recording booth. I don’t know why I didn’t think of this before. I’m a live singer. The honky-tonks on [downtown Nashville’s] Lower Broadway, that’s where I cut my teeth. That’s the kind of singing I do… I think a vocal booth is a great place for a great singer. When I say great singer, I’m talking about not just emotive but like technically good – can falsetto with a vibrato. You need that booth to capture every little thing about the voice. That’s not what my voice does. My voice, I come from the bluegrass school where you find a note and you fuckin’ hunker down on it and you hold it straight and long and true. You let the emotion of your heart come through in the tone of your voice, instead of using moves. I don’t know how to do moves.

“So I don’t need to be in the vocal booth. Here On Earth I sang on the bus. Lots of the vocals were done in Ross’ studio, which is the part of his house that the baby doesn’t go into… You can do vocals anywhere if you’re not looking for that Celine Dion-type thing. I discovered I sing much better when someone else is in the room with me, when I’m singing right here and Ross is sitting right here next to me and I can hold onto the mic. I’m grabbing the mic like I would on stage… I don’t have to be in an arena with the whole crowd there, but just having someone else in there with me [makes all the difference].”

On his '97 Martin HD-28

You mentioned your drummer, Steve Misamore, telling you how true Damn These Dreams is to your life. Is he the band member that’s been with you the longest?

“Yeah. We started playing Lower Broadway together 10 years [ago]. Well, gosh, we started back in ’99.”

That’s more like 15 years.

“Yeah. I just gave him a 10-year present. I paid for his pilot’s license training for his 10-years-in-the-band present. But now I’m realizing that’s probably his 12- or 13-year present.”

How long have the other guys been with you?

“[Steel guitarist and banjo player] Tim [Sergent’s] been there going on – well, this is his 9th year. And then the other three guys all came on after I did Up On the Ridge [in 2010]. Up On the Ridge was like a transformative record of my life. It really reset a lot of things for me. I brought in Dan [Hochhalter] on fiddle, Brian [Layson] on guitar and Cassady [Feasby] on bass. That would’ve been ’10. So this is their fourth year. I mean, just great players, great guys.

“I was doing that [CMT] Crossroads [taping] with One Republic and talking to Ryan Tedder about that, the importance of having that group of guys around you. It makes life really enjoyable. Because I don’t go out; I don’t do like social stuff in town. I’m at home. So when I go on the road, my band has to be not only my band but my best friends and my male support group.

You reference your “beat-up, old guitar” in I Hold On. What kind is it?

“It’s a Martin. It’s a 1997 HD-28. People see it and they think it’s a pre-war, like a ‘39 Martin, because it’s so beat up, so worn out. There’s a hole underneath the pickguard from me playing it so much, from my pinkie just going back and forth over that piece of wood, over and over. I wish that guitar reflected how good of a guitar player I actually was. It looks like I’m friggin’ Bryan Sutton, or Tony Rice. I’ve got a signature Martin deal now, but I still kind gravitate towards that old guitar. It’s got a lot of stories in it.”