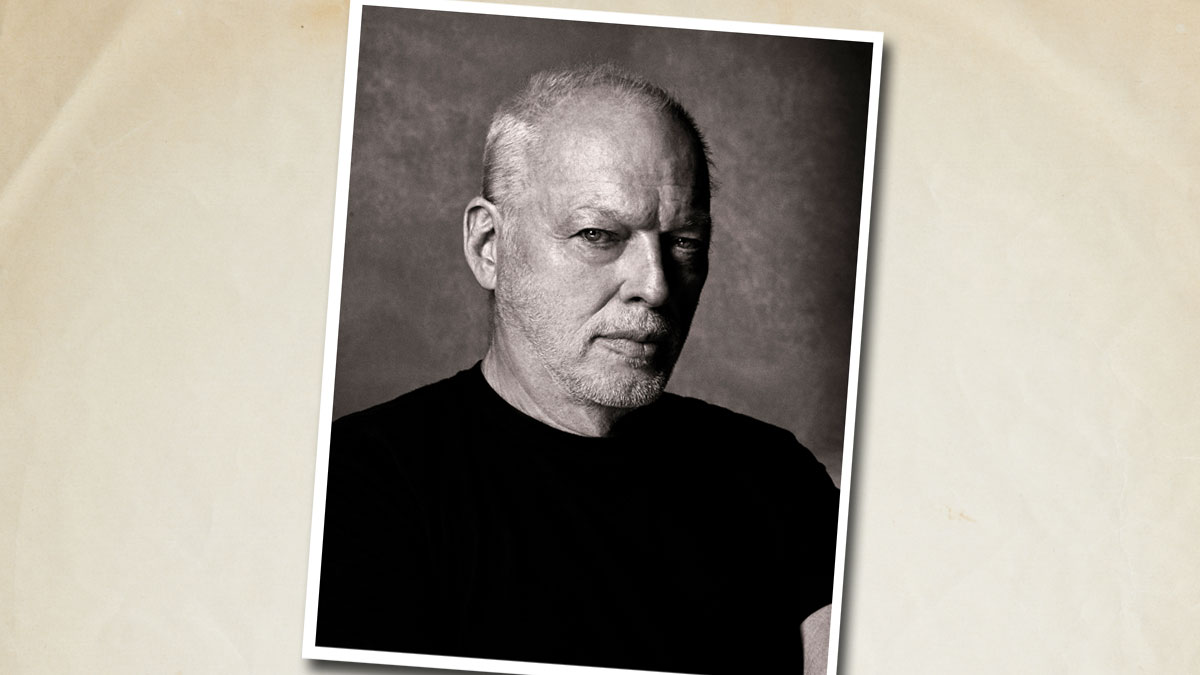

David Gilmour discusses new album Rattle That Lock

In-depth with the Pink Floyd legend

Introduction

David Gilmour’s new solo album, Rattle That Lock, is the follow-up to 2006’s On An Island. Here, he gives us an insight into his songwriting and recording process, discussing changes in his technique, the importance of early demos, and the gear he used to create the album.

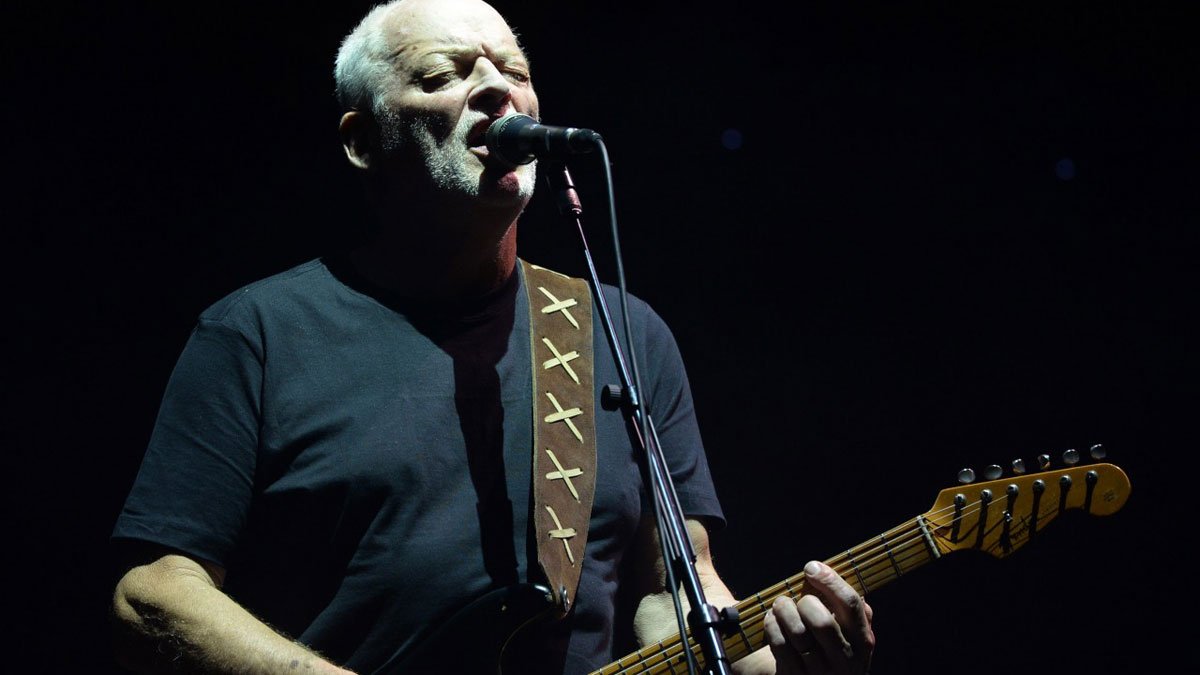

From the opening notes of 5 AM, the track that kicks off David Gilmour’s new album, Rattle That Lock, you know you’re in for something reflective. There’s always been something intimate and yearning about Gilmour’s remarkable guitar playing, but 5 AM conveys something much deeper; amidst the familiar longing he manages to wring out of the notes he so expertly delivers.

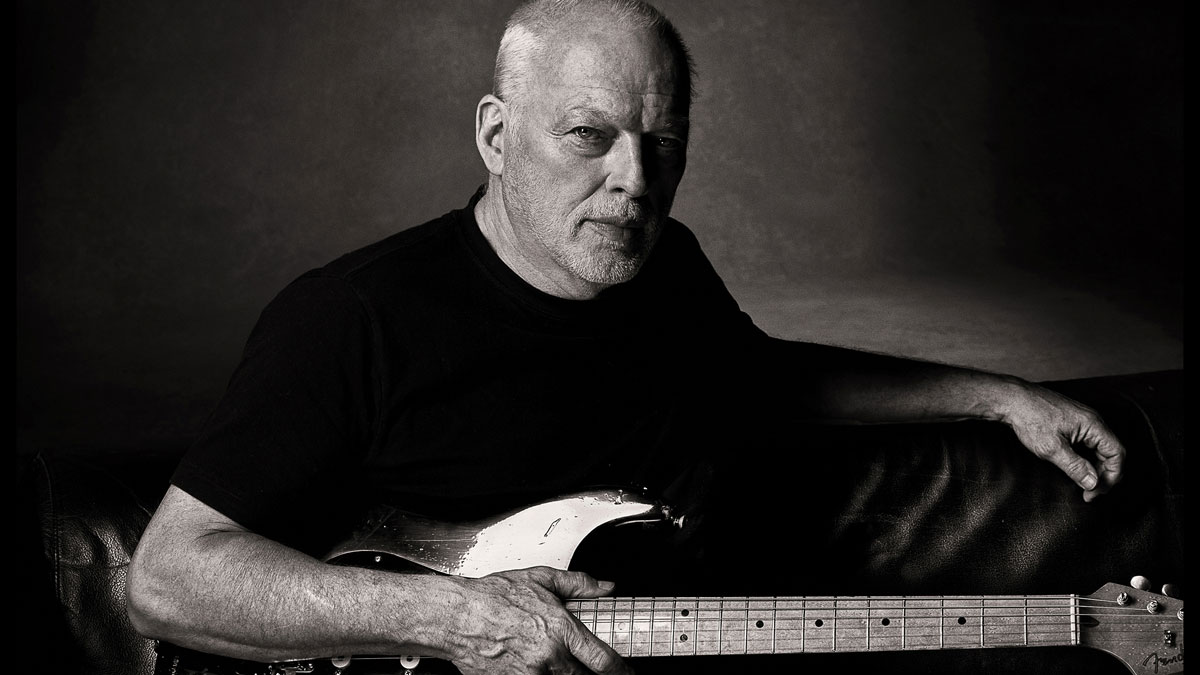

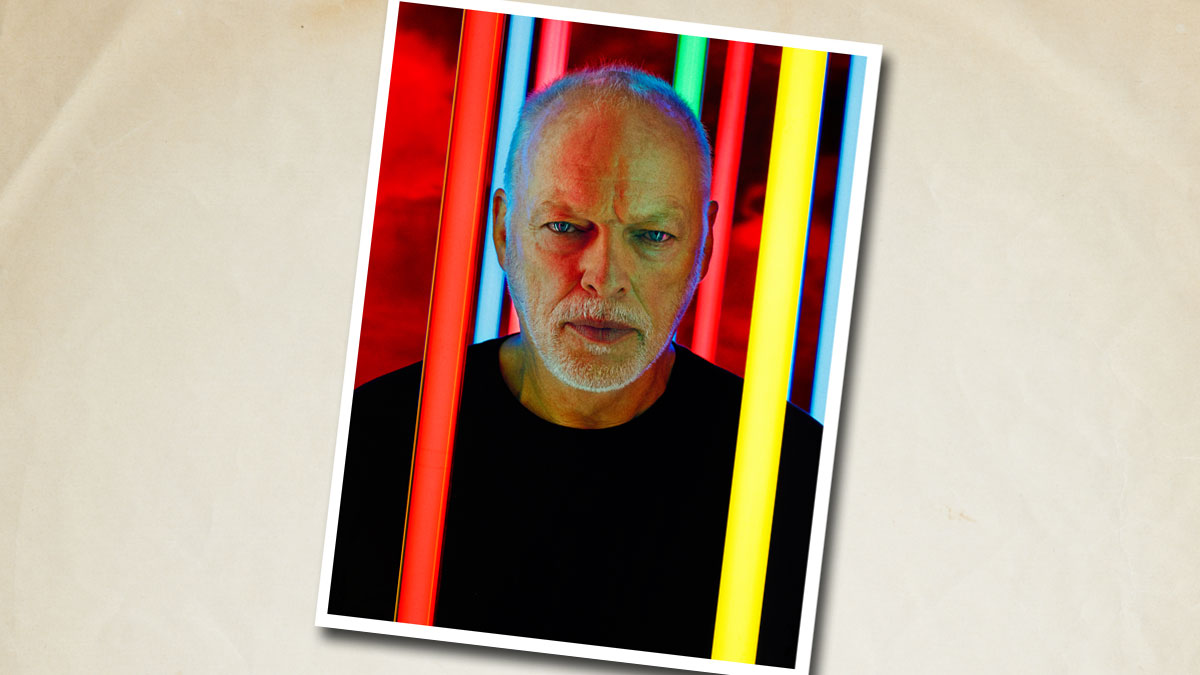

On the day we catch up, David Gilmour is a veritable fount of information

Seated in the London offices of his long-time publicist, Gilmour is fit and engaged. At the outset of our conversation, we remind him of a previous meeting at a party in the early 90s, around the time of the making of Pink Floyd’s The Division Bell, and that he’d said a total of about eight words the entire evening. “That sounds about par for the course,” Gilmour says with a wry smile.

In fact, both the keyboardist Jon Carin, who has worked with Gilmour off and on for more than 20 years, and Gilmour’s wife, the novelist Polly Samson, warned us prior to our conversation that the legendary guitarist isn’t exactly the most talkative guy.

On this occasion, however, Samson and Carin are wrong; on the day we catch up to discuss Rattle That Lock, his collaborative process and, of course, his inimitable guitar technique, David Gilmour is a veritable fount of information…

It’s been nine years since Gilmour’s last solo album, 2006’s majestic On An Island. It was followed by a lengthy tour, which included sold-out shows across continents and yielded a couple of live CD/DVD packages. But, as far as any further original material is concerned - nothing.

It seemed like radio silence was the order of the day in the Gilmour camp, only broken by the surprise announcement that a final Pink Floyd album, The Endless River, was to be released as a sort of memorial for Rick Wright who sadly passed away from cancer in 2008.

The album is mainly reclaimed from the vaults, and Gilmour acknowledged that it was an epitaph for Floyd, too, as he insisted that the band was finally done and that he was now focusing on his solo career.

Don't Miss

In pictures: David Gilmour's guitars, amps and effects

Nine years

So… nine years, then?

“It’s nine years, yes it is.” Gilmour ponders for a minute. “I have had a long and busy career, and I don’t feel it’s essential for me to keep going at the rate I was going when I was younger. I work until things start gathering momentum. This just happens to be that moment.”

We discuss The Endless River for a few minutes, and ask if sessions for Rattle That Lock began in earnest after work on that album was complete.

The difference is just the way that my mind and fingers are working at the moment

“It’s very hard to define the moment that you can say is the start point of it,” Gilmour says. “I’ve been working on bits of these songs for years, since On An Island, really. It gradually starts moving to a point where you start thinking, ‘Yeah, actually, I’m close to having something which I could turn into an album.’

“Of course, just at the moment when I had started that process and was getting a head of steam up and working on it, the Endless River project came into view, and I had to put this one on the shelf and do a few months of hard work on that one before moving back to this one. But here we are, we’ve now got there.”

While Rattle That Lock includes many of Gilmour’s signature sounds, it also dabbles in jazz and more modern-sounding song structure and polish. There are hints of Pink Floyd and Gilmour’s earlier solo work throughout, but it’s also a remarkable step forward for Gilmour as a solo artist, defining him more than ever as having a career outside the shadow of his former band. Is this something he feels, too?

“I guess every experience you have, every project you take part in subconsciously affects you in some way or another,” Gilmour reflects. “But trying to pin down what exactly has made any difference is kind of impossible, really. I have no idea. That just is the way that my mind and fingers are working at the moment. I can’t find another explanation.”

A Sony full of secrets

As we discuss the earliest days of demoing Rattle That Lock at home - some of which were recorded on an iPhone and used in the final mixes - Gilmour brightens at recalling his composition process.

Phil Manzanera was invaluable. He has a mind that can keep all those ideas organised

“These things will tumble out of a guitar or piano, and I’ll pop them down on my iPhone these days. Before the iPhone, it was something else: a MiniDisc player; before that, a cassette player; before that, well… God knows what else.

“It means that I never forget a new little snippet of music that comes to me, nine-tenths of which, of course, is rubbish. When you listen to them later, you go, ‘Oh God, not that.’ But it’s easier now, and has really helped the process of making this album.”

What did he do with the demos, and how did he choose which ideas to pursue?

“I turned them over to Phil Manzanera!” Gilmour says, with a hearty laugh. “There were about 200 little snippets, just odds and ends. I gave them to Phil, who whittled them down to about 30 ideas, and then we focused in on what were the best of those and what we wanted to develop - about 10.

“But we had plenty of ideas to draw from that were also good if we got stuck. And Phil was invaluable, in that sense. He has a mind that can keep all those ideas organised, and can make suggestions really quickly. That was enormously helpful.”

In the studio

Once in the studio, Gilmour tackled the songs with an energy that surprised even him, he says.

“Most of them were started off with a click track on a Pro Tools rig, and I’d do it all myself,” he says of the recording process. “At some point later, I’d get a drummer in. Stevie [DiStanislao], who came in for a couple of days, did dozens of tracks for me.” Another track, the jazzy The Girl In The Yellow Dress, was different.

I keep thinking that I want to do it all with a live band and get in a big room and record the song

“That was done live with a little jazz trio,” he says. “Jools Holland is on that. He wasn’t in the original trio that played, though. There’s a trio, a bass player, Chris Laurence, a drummer called Martin France, and a guitar player called John Parricelli - they were the trio on the original one.

“Then I did another session to try it again, but I used the same click at that session at Abbey Road, which Jools Holland and Rado Klose and a few other people were on. In the end, I just took those guys off that session and put them onto the other session. That did start off with a live track, but most of them don’t.”

Does he yearn for the days of playing live in the studio, with the interaction and creative dynamic it generates?

“I keep thinking that I want to do it all with a live band and get in a big room and record the songs,” he admits. “But I always seem to find myself at the end thinking that what I’ve got is so good that it would be hard to top it by doing that. But I’m always planning to do that on the next record.”

On A Boat Lies Waiting you can hear my son, who’s now 20, as a newborn baby

Does he feel - like many musicians - that it’s often hard to recapture the magic of the original demo?

“It’s exactly that,” he says, flatly. “On the demos for A Boat Lies Waiting, the piano is actually my demo, the main piano. That was recorded in my sitting room with me playing piano over 10 years ago on a MiniDisc recorder - a stereo MiniDisc recorder, a rubbish Sony thing. That’s how that piano was recorded.

“When you put it into Pro Tools and you’ve tidied up the dodgy timing, taken out the bum notes, and put a double bass on it to give it some rich bottom end and stuff, it starts to sound very good and it’s very hard to even think about replacing that.

“On A Boat Lies Waiting you can hear my son, who’s now 20, as a newborn baby - three months old or something - squawking on that track. That tells you how old that one was!”

A Whammy lies waiting

We broach the subject of his approach to the guitar on Rattle That Lock. While he is well known as being reluctant to examine his guitar playing and inspirations, today, however, Gilmour seems happy to ponder exactly those questions, and talk a little about his gear, too.

The acoustic on Faces Of Stone is, I think, the same one that I used on Wish You Were Here

“Well, I guess I just try to find what is the right sound and feeling for the track I’m playing on,” Gilmour says. “Sometimes it’s tricky to get to that. I don’t really think there’s anything particularly different or new in what I’m playing or the way I’m playing it.

“I tend to play more with my fingers than a guitar pick these days, for some reason that I don’t quite understand. It just seems to be the way it is. That might make a little bit of difference to the sound, but it’s not really anything I’ve been analysing or intending to do.”

When we point out that the playing and pristine-sounding acoustic guitar on Faces Of Stone was possibly a highlight of the album, Gilmour is matter-of-fact about the pedigree of the guitar he used.

“The acoustic on Faces Of Stone is, I think, the same one that I used on Wish You Were Here,” he says. “It goes back a fair old way.”

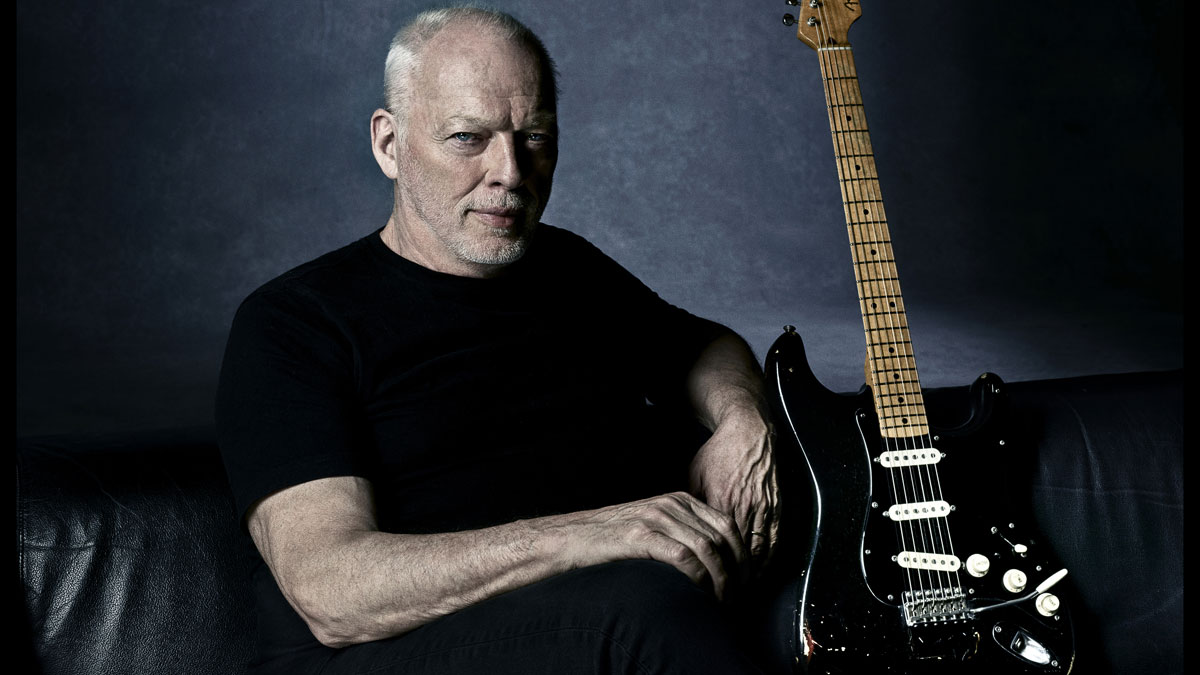

The black Strat

Phil Taylor, Gilmour’s long-time guitar tech, has said his boss has been using his fabled black Strat again, so we ask if Gilmour used that much on this album, and what his other go-to guitars were.

There’s something in the sound of that old one, and I haven’t got a spare for it

“Well, I used the Strat quite a bit,” he says. “I also have a black Gretsch Duo Jet that I used quite a lot. It’s a really old one. The old ones have got a very curious sort of hi-fi sound, a lovely top end. It has got a very different sound. I don’t know what it is about it that makes it have that sound, but I’ve tried to buy a spare to take on the road and looked at other ones and newer ones, but there’s something missing.

“There’s something in the sound of that old one, and I haven’t got a spare for it. If I break a string or something when I’m using it on stage, I have to switch to another one that’s okay, but it’s not quite in the same league. I don’t understand why those particular pickups on that particular guitar have got a sort of hi-fi top end. It’s unusual on an electric guitar.

“I also used a Gibson Goldtop, like the one I played on Another Brick In The Wall, but it’s not actually the same one. Those are the electrics I used - oh, and I’m using my old Esquire as well on a couple of tracks.”

As for amps, Gilmour is equally forthcoming: “I tried all sorts of different amps,” he begins. “I’ve got an old Fender Twin that’s pretty trusty and I’ve got a Hiwatt combo that, I guess, is 50 watts. I use my Yamaha rotating speaker cabinet quite often, mixed in with the other sounds…”

The other amp

Then he gets stumped. “What’s the other amp?” he asks no-one in particular. “I can’t even remember what the name of the other amp is, because it’s not written on it.

“It’s in a wooden case and I don’t even know the name of it [most probably his Alessandro Redbone Special - Ed]. It’s the one I used on the solo on The Endless River.”

I actually haven’t used a Big Muff for quite a few years. Certainly not on this album

Gilmour laughs, saying he’s just not that technical. But he’s willing to take a stab at the pedals he used in making the album. “I didn’t use the DigiTech Whammy pedal on this album at all,” he says, when we mention how arresting its use was on On An Island. “I did play with it a couple of times to try it, but it just didn’t seem like the right thing at this moment on this album. I couldn’t find a spot for it.

“I actually haven’t used a Big Muff for quite a few years,” he continues. “Certainly not on this album. I don’t think I used it on On An Island, either. The overdrive I tend to use is a [BK Butler] Tube Driver these days, often with a compressor feeding into it. On this one, it’s actually pretty much untreated. On a couple of tracks, I’ve just gone through with a compressor and used the output volume to be the overdrive. But yeah, I just fiddle until something starts sounding nice.”

As for how he’ll approach his sound for upcoming live shows, Gilmour chuckles.

“I don’t memorise what I use, if that’s what you’re asking,” he says. “I just don’t work that way. I probably should try a bit harder to make notes of these things and sort all that out, but I’m afraid I don’t. I just try to get something that sounds similar when I go into rehearsal. I just press a button on the pedalboard on stage, see what comes close, and then stick with that.”

Don't Miss

In pictures: David Gilmour's guitars, amps and effects