"He showed me some things that Charlie Patton and Robert Johnson had taught him – he knew those people": Hubert Sumlin, Howlin' Wolf and their legendary blues legacy

"Mick Jagger walked up to Wolf and said; 'I hope you didn't mind that we cut Little Red Rooster?' Wolf just smiled and said: 'No, man… you guys have put me on the map!'"

The late blues scholar, musician and writer Julian Piper interviewed Howlin' Wolf guitarist Hubert Sumlin back in 2006 for Guitarist magazine. Hubert reflected on his career with Wolf, his friendship with the Rolling Stones and the direct influence of Robert Johnson and Wolf's mentor Charlie Patton. Hubert passed away on 4 December 2011.

"Maaan, Keith's okay, he's just sitting around playing some blues - I been around his house and we been recuperating together!'' Hubert Sumlin's infectious laugh ripples down the transatlantic phone line from his home in Milwaukee. He's a man who laughs a lot – you rarely see a photo of Hubert not smiling – and, all things considered, it's probably just as well he's got a sense of humour.

During the last few years he's lost a lung, had heart surgery, his house has been flooded - losing him his prized collection of vintage photographs - and his wife passed away. All in all it makes Keith Richard's unfortunate incident with a coconut tree seem rather trivial in comparison.

"Keith's a wonderful person, they all are," Hubert continues. "Came to my rescue when I was sick, the band paid all my bills. I was in bad shape at the time and I can't say enough good about them."

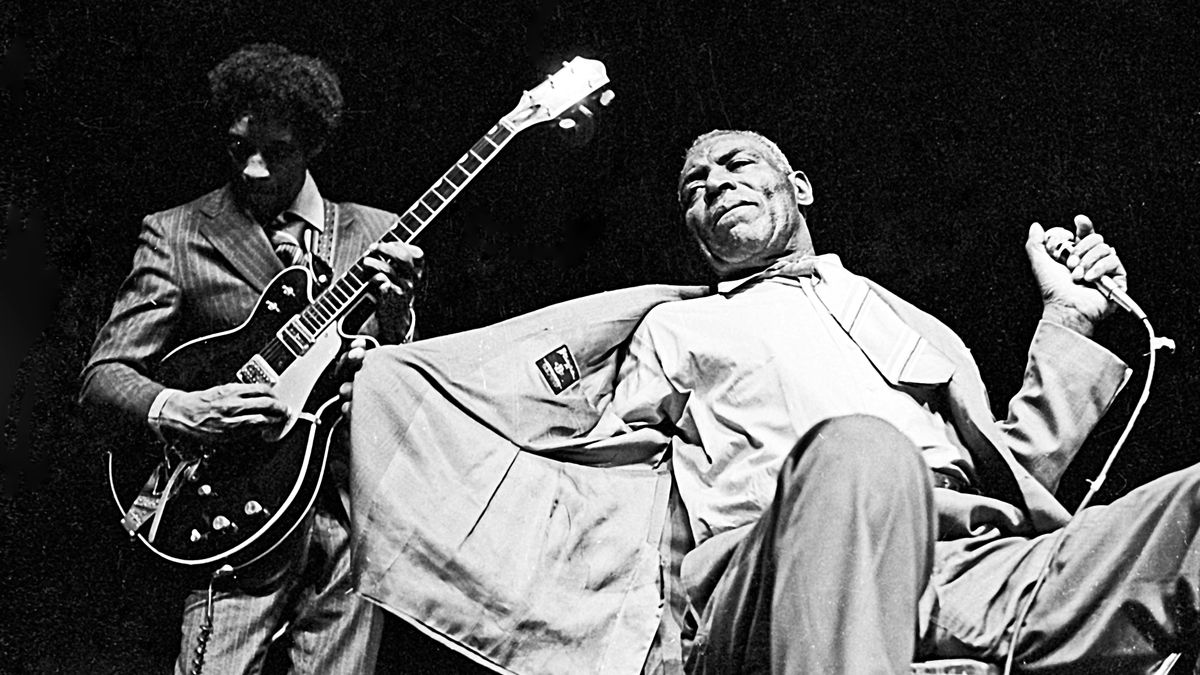

The blues world has seen many great partnerships in its time - Buddy Guy and Jr Wells, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Muddy Waters and Little Walter – but the legendary status afforded Hubert Sumlin and his old boss Chester Burnett, better known as Howlin' Wolf, is nothing short of jaw-dropping.

A consummate performer, Wolf would think nothing of entering a club on all fours snarling, a handkerchief tied to his belt to imitate a tail, or rolling on the ground bellowing

No-one has ever sounded like the Wolf and no-one ever will. Gifted with a huge rasping feral voice so powerful that it could allegedly blow valves in a mixing desk, Wolf was the indelible link between the primal cottonfield blues of his mentor Charlie Patton - who taught him to play guitar - and Led Zeppelin, Cream, and Jimi Hendrix.

A consummate performer, Wolf would think nothing of entering a club on all fours snarling, a handkerchief tied to his belt to imitate a tail, or rolling on the ground bellowing. His songs like Smokestack Lightning, Killing Floor, The Red Rooster, Back Door Man and Evil, became anthems for a whole generation of musicians on both sides of the Atlantic; Hendrix's anarchic live version of Killing Floor at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival was a highlight of his early career.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

But as much as the Wolf was revered, so too was his guitarist Hubert Sumlin. A slight, unassuming man who usually stood quietly picking on a never-ending variety of guitars – everything from a Goldtop Les Paul to a quirky Italian Bartolini which looked like a prop from the Starship Enterprise – it was Hubert's spiky, icy cool lead lines that nailed the songs time and time again.

On just about all the numbers we recorded Wolf always turned me loose, let me do what I wanted

Uniquely, and unlike anything recorded up to that time, Sumlin's solos and intricately crafted riffs owed little to the influences of either Mississippi, or the increasingly popular 'City Blues' of guitarists like BB King and Freddie King.

"On just about all the numbers we recorded Wolf always turned me loose, let me do what I wanted,'' Sumlin recalls. "One time the Chess brothers hollered at me in the studio when we recording Shake It For Me… Leonard Chess said; Hubert, turn it down, turn that thing DOWN! Wolf just stopped the music and pointed across the room at where they were in the Control Booth. Wolf goes: When there's something to be said, let me tell him, not you! You fools operate the studio and leave the music to me. C'mon man, let it rip!"

"I wasn't really loud,'' Hubert says indignantly. "I can hear and I can hear good - I was just playing with the guys. The guitar sounds upfront on the records we made but it wasn't like that when we recorded it, we needed to hear one another. The way we did it everyone would be heard - the piano player, bass player, drummer - but when I played my solo, maaan you better get out my way!''

Scowlin' Wolf

But if the Wolf was generally supportive of Hubert's musicianship – he invariably referred to the younger man as his 'son' – he could also be a hard taskmaster. Stories abound of the fights he and Hubert had on and off stage – on one occasion he allegedly knocked out his guitarist's front teeth – and as Hubert admits, it was Wolf who was responsible for inadvertently forging the fluttering style that has become his trademark.

He was so powerful at times I wouldn't even dare speak to him

"He was so powerful at times I wouldn't even dare speak to him! One time, Wolf told me to put the pick down because I was playing too loud,'' Hubert says. "He told me; Put it down, use your fingers like everyone else. I told him that's what I started out playing with and that's what I was going to go on using. Wolf turned to me and shouted: No you ain't, you fired!'' Sumlin laughs out loud.

"So I went home and started practicing but couldn't believe it - I'd been playing with this guy eight years and now I'm fired! Wolf's time was always split time, 12 bars, six, 11 - anything.'' Hubert explains. ''I'm set in my ways and when he told me to put the pick down I just felt like hitting him, but I went home and practised playing without it.'' He chuckles.

"My fingers got so sore but I went back to work and that evening I was the last guy to get up on the bandstand. Wolf says; Ladies and gentlemen, this is my son - let's see if he's got it now! We played Smokestack Lightning and he said; Why didn't you play like that before?"

Right now, Hubert's on a bit of a roll. His last album, About Them Shoes, boasted heavyweight contributions from Eric Clapton and the aforementioned Mr Richards, and he's also stepped onstage in the UK for a couple of dates with the Rolling Stones.

They didn't want him on the show but the Stones insisted

It's a friendship and mutual admiration society that goes back to 1964 when the Rolling Stones recorded Little Red Rooster, and later had Howlin' Wolf support them on their 1965 Shindig television appearance in Los Angeles. Although the Wolf was suitably restrained, one can only speculate how the mothers of America reacted to their daughters watching the Wolf rip the place apart.

"That's right!" Hubert exclaims. "They didn't want him on the show but the Stones insisted; I used to see them guys all the time, and when I first heard the Stones version of Little Red Rooster I couldn't believe it! Then when Wolf and Mick Jagger first met, Mick walked up to Wolf and said; I hope you didn't mind that we cut Little Red Rooster? Wolf just smiled and said: No, man… you guys have put me on the map!

"They opened my path because they were well known before they ever first got to the States, and they tore up things here. I fell in love with them, Muddy and all of us felt the same way. Did we mind?" he laughs. "No, I just thought, Amen, hallelujah, at last!"

Rooster booster

If the Top 20 success of Little Red Rooster was a phenomenon, even more bizarre was the success that Howlin' Wolf and Hubert enjoyed a few months later with Smokestack Lightning. In the wake of The Rolling Stones' increasing notoriety, the UK was in the grip of R&B fervour.

Pye Records had been releasing Chess recordings for a couple of years, and with their distinctive red and yellow label and imposing R&B logo the Chess songs by artists like Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Sugar Pie Desanto and Tommy Tucker were just about the hippest thing on Mod dance floors from Brighton to Wardour Street.

Smokestack Lightning was a lick he got off Patton

Smokestack Lightning's menacing loping riff, picked by Hubert over a hypnotic bass line, instantly became an obligatory number in the setlist of any self-respecting R&B band throughout the land. Incredibly, the song even reached number 42 in the pop charts and a few more sales might have seen the leering Howlin' Wolf on Top Of The Pops alongside Engelbert Humperdinck and Cilla Black. Now that would have certainly been a sight to see…

But as Hubert readily admits, the tune owed its origins to something Charlie Patton taught Wolf back in his Mississippi plantation days. "Smokestack Lightning was a lick he got off Patton. Wolf had learnt them so well that he fell in love with the music. Robert Johnson and Patton were around when I was still a kid, so I'd never heard that stuff, but Wolf learnt me a lot. He showed me some things that Charlie Patton and Robert Johnson had taught him - he knew those people, showed me old stuff that they were doing."

Sumlin chuckles as he recalls how Wolf and Charlie Patton originally met up. "He went to see Patton playing at this joint out in the country but he was too darned young to get in. He went up and crawled underneath the floor - the house was on cinder blocks - but people were stompin' around so much that the floor fell in on his head. Patton reached down and sat him up saying; Look here young man, this is what we gonna play, you watch me. I see you gonna be alright!"

In 1970, Sumlin and Wolf flew in to London to record an album that became known as the London Howlin' Wolf Sessions. A bizarre attempt by all involved to recreate the Wolf's finest hours using a bevy of British 'name' musicians including Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr and Bill Wyman, it remains an intriguing piece of musical history.

Because he didn't have a slide he'd broken the end off and he'd cut his fingers bad, there was blood everywhere!

Clapton had been reluctant to play, preferring that Hubert play lead guitar, but it was not to be. As a result, a tired-sounding Wolf is to be heard patiently trying to explain the changes on Little Red Rooster to an obviously over-awed Eric Clapton.

It's a day that Hubert remembers well. "On Little Red Rooster, Wolf is playing the guitar and I'm right in the background," he recalls. "Wolf ended up playing the slide with a milk bottle but he was in a mess! Because he didn't have a slide he'd broken the end off and he'd cut his fingers bad, there was blood everywhere!

"But I never will forget us cutting Shake For Me and Going Down Slow, every time I hear those tracks it feels like the Wolf is still around. Even now, I can't believe he's gone…"

“With Off The Rails, I was stuck – didn’t quite know where to finish it – so I went and saw Killers of the Flower Moon”: Jerry Cantrell reveals how Jeff Beck and Martin Scorsese influenced new solo album I Want Blood

“That very first meeting we had was quite intense. He just wanted to know how thoroughly we knew the subject”: Becoming Led Zeppelin filmmakers tell of their first meeting with Jimmy Page

Most Popular