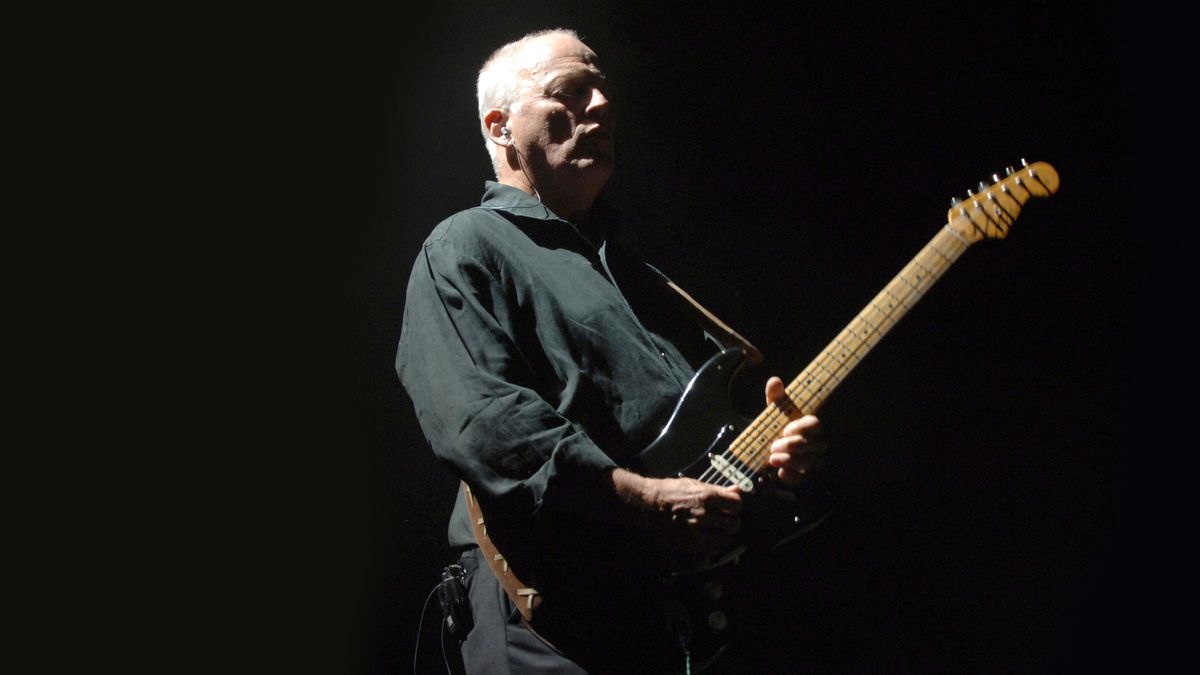

"The fingers aren't very fast but I think I am instantly recognisable": David Gilmour classic guitar interview

Gilmour on the brief Pink Floyd reunion, On An Island and the art of the live guitar solo in this 2006 interview

When the Pink Floyd guitar legend returned in 2006 with his first solo album in over 20 years and a year on from Pink Floyd's surprise Live 8 reunion, it was clearly time for a chat...

Passing through an ancient vaulted tunnel, the visitor to Astoria emerges into an impeccably kept garden that slopes gently downward to the Thames. David Gilmour's houseboat studio rides at anchor by the river bank, just beyond a leafy grove of bamboo and willows.

The boat, too, is named Astoria. It's not a large craft; there's barely space for a well-stocked control room, dominated by a huge Neve mixing console, and a small elegant parlour that doubles as a tracking room. A narrow passageway panelled in dark wood connects the two spaces, also giving access to a few tiny side chambers along the way.

"ou could say that after being a professional musician for 40 years I should know what I'm fucking doing. But I find it best to just hurl myself into it in a different way each time

The boat was built in 1912 by English showbiz entrepreneur Fred Karno. "He was the guy who discovered Charlie Chaplin and Stan Laurel," Gilmour explains. "He wanted to have his own private home place, knocking shop, whatever... It was never built to sail. It's strictly a houseboat. If you want to move it, you get a tug and tow it. My idea was to make it as good in here as we can reasonably get it, sound-wise, without fucking with the space too much."

This boat is where Gilmour recorded much of Pink Floyd's final two albums A Monetary Lapse Of Reason (1987) and The Division Bell (1994), and it was also the main site of sessions for Gilmour's new solo album, On An Island.

The record is very much a reflection of the place where it was made - serene, unhurried. Gauzy layers of shimmering sound unfold at a stately pace, providing a lavish backdrop for Gilmour's soaring guitar and that ethereally expressive vocal style well-known and loved from Pink Floyd's catalogue of classics.

There are occasional excursions into the blues and other slightly rougher terrains, but mostly this is a record for gazing peacefully at the river "I was just letting it all flow out as naturally as it can," reflects Gilmour. "There are quite a lot of those melancholy major seventh chords and 3/4 waltz tempos. That must be the mood I'm in."

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

To see where On An Island was made is to understand why Gilmour had to be almost forcibly pried from the studio to take part in Floyd's reunion at Live 8. Nobody thought David Gilmour would ever get on a stage again with Roger Waters after the pair's many quarrels. They did just that, however.

The way I play melodies is connected to things like Hank Marvin and The Shadows

Waters has since made noises about rejoining the band but Gilmour isn't interested. The guitarist seems quite content just being David Gilmour and has nothing left to prove. He's a household name among the classic rock crowd, and for a lot of younger guitar fans he's the only 1970s guitarist that matters. For many he's the missing link between Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Van Halen...

"I'm thrilled if that's the case," he laughs. "It's taken me a long time to achieve that. I didn't start figuring in guitar-playing polls for a lot of years. I think one thing about the fingers and brain that I have been given is that the fingers make a distinctive sound. The fingers aren't very fast but I think I am instantly recognisable. I can hear myself and just know that it's me. And other people do too.

"The way I play melodies is connected to things like Hank Marvin and The Shadows - that style of guitar playing where people can recognise a melody with some beef to it."

On An Island is only Gilmour's third solo album. The prior two were recorded during troubled periods in Pink Floyd's career; David Gilmour (1978) was a way of blowing off steam after the difficult recording of Animals, and About Face (1984) was a full-scale effort on Gilmour's part to launch himself as a star in his own right after Waters left Pink Floyd and the band all but fell apart following the release of The Final Cut. On An Island comes from a very different place. Life is good for David Gilmour right now...

I think that the work I'm doing now is as good as anything I've ever done

What motivates you these days? Your place in rock history is assured, you're very comfortably off. What drives you to make an album?

"That's what I do. I'm a musician. I make music. It's in my blood. The difference is that these days I'm not driven to do it all the time. Honestly, music isn't my first priority anymore. Family is.

"Now, I could see where someone could think that when I person says music isn't his first priority any more, the quality of the music might therefore suffer. But once I get going I do get rather perfectionist. And I think that the work I'm doing now is as good as anything I've ever done. I think On An Island is a really good album. I'm very proud of it."

Was your new album a bigger priority for you than doing Live 8? You declined initially...

"I did, yes. And I declined because I was in the middle of making this album. Also I thought – correctly as it turned out – that it would open a can of worms: Pink Floyd reformation stories. I selfishly didn't want to be inconvenienced by all the things I knew this would throw up. So Bob Geldof tried quite hard to persuade me.

"It's not that I didn't support what he was trying to do. I just thought he'd do just as well without us. But then Bob got Roger involved and he persuaded Roger to call me and ask me."

Was it surprising when Roger called you?

"Yes, very. And after Roger called I thought about it; I really probably would kick myself afterwards if I didn't do Live 8. There were many good reasons for doing it. The proper, and best, reason was what the event hopefully did achieve. And it put some of the bad blood between Roger and myself behind us."

How much rehearsal went into Live 8?

"We did three days of rehearsing together. But I did over two weeks on my own. I made a CD of the set and had it at my home studio. I'd blast it out through speakers, play guitar and sing along to it three or four times a day every day for a good couple of weeks. I wanted to be very 'on it'.

"I knew it would be a nerve-wracking experience and I wanted to be able to do it like falling off a log. I didn't want to be nervous and tense about not being 100 percent certain that I knew exactly what I was doing every second."

When you did the first guitar solo in Money at Live 8, it was pretty much a note-for-note duplication of the solo on the album. Do you feel you owe it to the people to give them a signature solo like that note-for-note? How does that balance against spontaneity?

"Well I think it is a balance. When I go to hear other bands and they launch into a big pop hit of theirs, if the guitar player goes off in a completely different direction I'm pissed off, frankly.

"I'm thinking; that ain't the way it is, that's not how it's supposed to go! And so my tendency is to start off pretty much like the record and then see how I'm feeling. If I move off it and it feels good, inspired and original, then I'll stay off the beaten track.

"But sometimes I realise I'm off the beaten track but it's just dull. Then I'll go back into the safety net of pretty much the original solo because I know that will turn a lot of people on more. So yeah, it is a balance."

But can you always get back to the recorded version, though?

"I can't always. But in the beginning of the end solo of Comfortably Numb, there's that note on the seventh fret of the G string – a big harmonic. I always try to start that solo with that sound and play that first line. It seems daft not to!"

Which of your many Strats is that black one you played at Live 8?

"I've been using that one since about 1970, it's the one on Comfortably Numb. I bought it at Manny's in New York. I've always used it as a testing ground for trying all sorts of things out. It's had a few different necks on; the original had that bullet [truss rod] and a larger headstock. And it has different pickups.

"Years ago, I met up with Seymour Duncan and we picked three really nice sounding pickups he had. We rewound those three and they've stayed on it ever since. But I've always considered that to be my bodge-up guitar that nothing is sacred on. I've had holes drilled in it. It's still a good guitar."

In pictures: highlights of David Gilmour's astonishing guitar auction

You have many Strats; how do you decide what to use on a track or live date?

"For many years one of the problems of touring was [RF] interference - especially if, like me, you're the sort of bastard who tends to use a huge pedalboard.

"Those effects pedals really tended to pick up interference, as did the dimmers on the lighting rigs. And with Pink Floyd we did have extensive lighting rigs, which buzzed horribly. But when I first heard of and got hold of those EMG pickups, they stopped that dead. They sounded great - a very full and rich tone - but they didn't sound quite as 'Stratty' in some ways.

"There's something in the thinness and particular range a Strat has that makes it a Strat. With EMG pickups you tend to lose that a little bit. But nowadays, of course, everything is much better shielded and the lighting rigs operate from a completely different generator. Things are set up far better. So these days I can go back to using the older Strats live and I've been using my black Strat again, as I did at Live 8."

Roger has been pretty vocal in the press about how positive the experience was for him. He seems to be saying he'd like to do more – to reconvene Pink Floyd on a more regular basis. What are your feelings towards that?

"I have great pride and affection for most of my Pink Floyd career. Musically and artistically it was very satisfying. But it's the past for me. Done it. I don't have any desire to go back there.

Doing a tour without making a record would just be doing it for the money

"Doing a tour without making a record would just be doing it for the money. And thinking about making a new record with all of us, including Roger, I just don't think that would work. Roger and I have had too long being horrid little despots. I just don't think it would make me a happier human being. Sorry, I'll pass on it."

It's nice the way the title track On An Island kind of floats between an E minor and a G major feel?

"G6. Yeah, it's funny how these things come out. It sounded wrong in G and it sounded wrong in E minor. So I did it in E minor and used the G root note. Originally I just used the G root note, but something made me realise I should slide between the two. It creates its own sound."

Is that triple-meter time signature a good one for soloing? You've used it a lot...

"That's a funny thing too. I write more in 3/4 time and 6/8 time than I do in 4/4. One of the things we were looking for in putting this album together was to try and balance out the 3/4s with a few more 4/4s. I guess I'm just a waltz time sort of guy."

What electric guitar and amp did you use for that On An Island solo?

"That one was the old black Strat I mentioned earlier, through a Hiwatt combo. I've got a very old Fender tweed Twin - a lovely sounding amp - but I couldn't make it work for that track so I went to the Hiwatt instead. I have a Hiwatt combo and a Hiwatt 100-watt head and 4 x 12 cab in this room. It's a bit of a problem. A 100- watt Hiwatt doesn't really like being in a close space like this. So getting the right amp that really likes the room is tricky."

I try to make it so that when I go for a solo, the sound is really together and well thought out because very often the first take is the best take – except when you try to plan it that way

For guitar solos, do you write them out in your head first, or do you just blast away and comp the best bits?

"I try to live with the track before I even touch a guitar that's going to play a solo on it. When I'm working at home it's very easy to just pick up a guitar, not work on a sound very much and just play a little bit.

"At first I find myself loving what I do that way. But ultimately I think it's not too good and want to change some bits. But then I find myself not able to match the sound of the original solo, or sometimes wishing for a better sound. So I try to make it so that when I go for a solo, the sound is really together and well thought out because very often the first take is the best take – except when you try to plan it that way. Then you're still struggling with the same damn solo three days later. So really I have no method.

"You could say that after being a professional musician for 40 years I should know what I'm fucking doing. But I find it best to just hurl myself into it in a different way each time."

Is the Glissando effect in the guitar solo for The Blue a [DigiTech] Whammy pedal?

"Yes. I love it. You've guessed what it is, but I generally don't like to say how that's done. I love driving people crazy. They come and say, How the fuck did you do that? I've been working for months trying to get that. And I say, It's just a pedal! I used it on Marooned from The Division Bell.

"It's the same sort of thing - gives a whole extra dimension. It had a flavour of that old album, Songs Of The Humpback Whale, where they recorded whale noises. It's that floating thing. Both Marooned and The Blue are pieces of music that remind me of the sea..."

This Heaven brings out some of your blues influences, doesn't it?

"That was just another little jam from my front room. Phil Manzanera took it away one day. He'd often do that because he's got a studio in London. He took it there and cut a one bar loop out of what I'd done, sped it up slightly and changed the key.

"My original demo was in E minor; he took it up to F minor. We added drums to that loop and turned it into a track. And obviously the blues is a large influence on here. But all my playing is rooted in the blues."

As a lap and pedal steel player, are you particularly fond of the Weissenborn acoustic lap steel that BJ Cole plays on Then I Close My Eyes?

"Definitely. That's my Weissenborn he's playing. I played it on Smile. But he was over my house one day and I had him play it on Then I Close My Eyes. The Weissenborn's a lovely thing. I always felt pretty good and comfortable on side instruments There are places between the notes where I really like to go and you can go there on slide instruments."

When we got to The Dark Side Of The Moon and we were doing The Great Gig In The Sky, I invented a different tuning for that because it's hard to know exactly what is the best tuning on slide

That's become another signature thing for you...

"When I started doing pedal steel and lap steel at shows, the first track I can remember using it on consistently was One Of These Days, where it's tuned to an open E minor chord. And then when we got to The Dark Side Of The Moon and we were doing The Great Gig In The Sky, I invented a different tuning for that because it's hard to know exactly what is the best tuning on slide.

"Open tunings are by definition quite restricting. So I found a tuning which is kind of an open G6. The top four strings are the same as a regular guitar: EBGD. And if you tune the bottom A down to G and the E down to E, you get a 5 string open G chord, but you've got a three-string E minor chord at the top. So you can do quite effective majors and minors. And that's the tuning I tend to use quite a bit, the one I originally laid down for The Great Gig In The Sky.

"By that time I needed to have two steel guitars on stage. The pedal steel was a bit cumbersome. It had more strings than I could actually deal with - eight strings on each neck - so what I ended up making was a six-string slide. I bought two cheap Fender copies called Jensens. They cost nothing in England in the early 1970s. I got a red one and a yellow one and eventually I put Fender pickups in them. That's what I used for a long time: one tuned to the open E minor and one tuned to open G6."

The DVD version of 1994's Pulse is significant because it was the first time you'd done The Dark Side Of The Moon all the way through in many years.

"Lyrically, The Dark Side Of The Moon is really Roger's baby. So sometimes I'd get a slight feeling of minor discomfort doing it without him. But not sufficient to make me think we shouldn't do it. It's part of our oeuvre. I spent a lot of time and sweated blood making that record, and doing it again live was always my ambition."

“With Off The Rails, I was stuck – didn’t quite know where to finish it – so I went and saw Killers of the Flower Moon”: Jerry Cantrell reveals how Jeff Beck and Martin Scorsese influenced new solo album I Want Blood

“That very first meeting we had was quite intense. He just wanted to know how thoroughly we knew the subject”: Becoming Led Zeppelin filmmakers tell of their first meeting with Jimmy Page

Most Popular