Carlos Santana talks Miles, Hendrix and his new memoir, The Universal Tone

Carlos Santana admits that his upcoming memoir, The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light, doesn't follow the usual well-trodden path of other rock star tell-alls. Writing with what he describes as a "celestial memory," Santana sidesteps salaciousness for spirituality while taking readers through the touchstone moments of his remarkable life and career, from a scrappy childhood in Tijuana to hitting the stage at the Fillmore during the Summer Of Love, to triumph at Woodstock, international success and the many musical vicissitudes that have attended his career over the past five decades.

"A lot of musicians write that one kind of book, but that's just not my trip," Santana explains. "Writing this book, I wanted to respect the three words that I love every day: Elevate, transform and illumine. That goes for off stage, on stage, at home, anywhere. When you’re able to elevate, transform and illumine, you’re able to get beyond fear. Fear has a way of making people cynical; they become the worst version of themselves.

“There's something I've grown to realize in life, and it's something I experienced in writing this book," he continues. "I want to be the opposite of cynical. I want to be vulnerable, like a seven-year-old child, with openness and trust and purity and sincerity." He laughs, then adds, "Let's face it, man. Being cynical is dead in the water. It’s a waste of time, a waste of everything. I hope this book can maybe help some people get beyond all that negativity.”

Santana sat down with MusicRadar in New York City recently to discuss some of the revelations in the book and to reflect on a few of the memorable musicians and industry professionals who have helped shape his music over the years.

Carlos Santana's The Universal Tone: Bringing My Story To Light will be published on November 4 by Little, Brown and Company. You can pre-order the book at Barnes & Noble.

The book isn’t a year-by-year-discography, but you do write that you’re planning that for another book. Is that something you're actively working on?

“Yeah, I think I’d like to put out two more books. One would be more of an account of the making of each album, and the other would be more of a… I don’t know what you’d call it. I go on Facebook a lot, three or four times a week, and I write down thoughts that I hope will help people crystallize their existence.

“It’s my own personal meditation, but I think it’s important to share. Whatever’s happening to me at a particular moment can, from what I understand, help people at that same moment in their lives. Because they can go the wrong way for a long time, and they can be very, very hurt by certain decisions. I don’t want to tell people what to do or how to think or what to be or how to do it, but I do want to invite them to say to themselves, ‘I am significant and meaningful, and I can make a difference in the world. I am light, and with that light I can create miracles and blessings.’ The more you say this, the less suicides you’ll have, the less you'll see people killing each other. We’ve got all of these extremes of fear. I like to accentuate light instead of fear.”

You write about your parents a great deal. Your father was a violinist, and you yourself tried the instrument for a time. Do you think that violin playing in any kind of impacted your approach to the guitar?

“Thank you for mentioning that. Yeah, I think it did impact the guitar playing, sure. It was a positive influence in my life. Think about it: When you play the violin, you have to hold notes longer with the bow, which is just like sustain on the guitar. Peter Green or Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Buddy Guy – certain people have that sustain when they bend the notes. From playing the violin, it was easier for me to jump from the bow to using feedback. Sure, I see that. It's there.”

The meaning of The Universal Tone

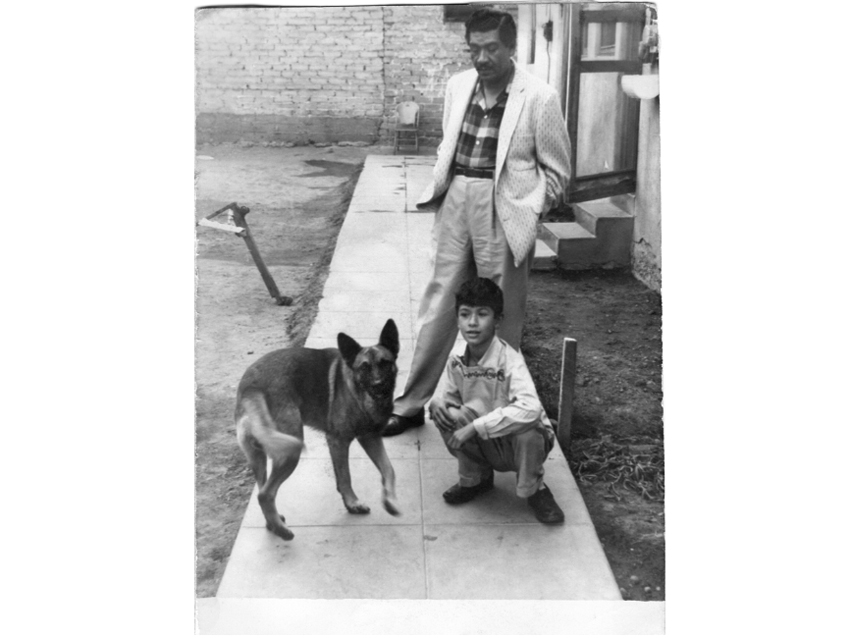

Above photo: Carlos with his father and the family dog Tony in Tijuana, 1958.

The title Universal Tone – you liken it to Coltrane’s A Love Supreme. When did the concept and the name hit you?

“Probably in 1972. I was hanging around with my ex-father-in-law – well, this was before he became my father-in-law; he passed in 2000. I was spending time with him back then, and he was checking me out; I was a new person, gravitating toward his daughter Deborah. He wouldn’t say much, but one day he said, ‘Do you believe in the Universal Tone?’

“I said, ‘Absolutely. John Coltrane, A Love Supreme.’ Even then I knew. But it wasn’t just that; it was All You Need Is Love, Imagine, Bob Marley’s One Love – any song that becomes outside of time. It's a song, a rhythm or a melody that is beyond gravity and beyond time. That’s what I’m talking about. That’s the Universal Tone.”

It was a shock to read that you were molested by a man when you were 11. Is that something you kept inside for many years? Was the incident hard to revisit?

“It was important for me to reveal that because there’s a lot of men and women who have gone through it. I had to say to them, ‘I’m healed by that. I’m healed by reducing the person who did it to me to a seven-year-old child.’ It took about a year, year and a half. Once I did that, I saw light behind him, and I told him, ‘I want to forgive you and send you back to this light. I’m not going to send you to Hell, because then I’d be going with you.’ You understand what I mean? It took me to the year 2008 to get to that point. Once you do that, though, you’re free.”

In 1961, you were turn on to the electric guitar. Did you feel as though you were a natural? In the book, you don’t talk about it being a struggle to learn the guitar.

“Oh, yeah, I knew was a natural. I was destined to play the electric guitar. It felt as natural as a dolphin going up and down in the water or a bird flying in the sky. I had no reservations or doubts that I could do that or be that. Once I saw Michael Bloomfield and BB King and Peter Green or Jerry Garcia, I knew that I could stand next to them, without a shadow of a doubt. It was there – it was in me. Otis Rush, Buddy Guy – I’m mentioning giants. And I’m a giant. [Laughs]

“But I say that with humility and conviction. Being over the top egotistical or shortchanging yourself as being nothing – it’s the same thing. You have to say, ‘I am equal. I am one. I am no less and no more.’”

"Cut and shoot music"

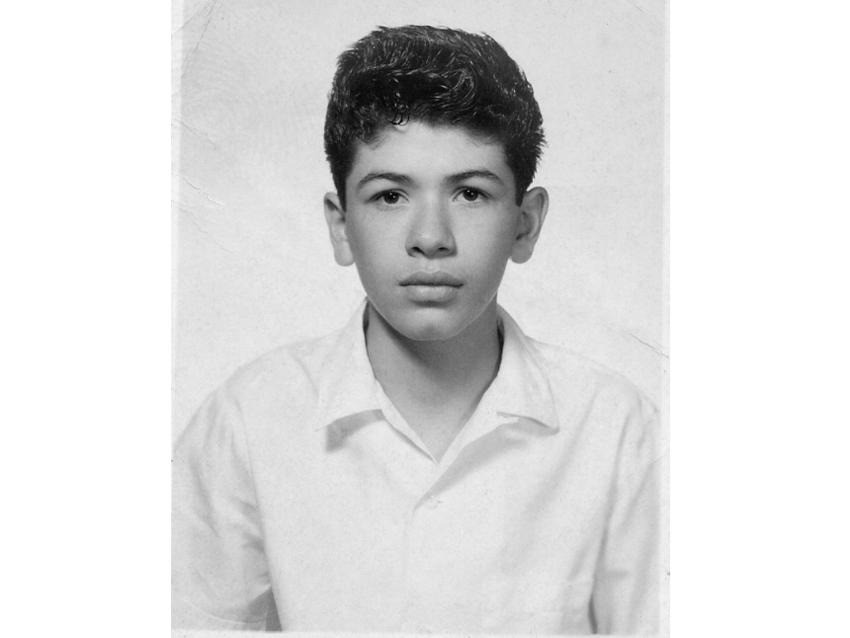

Above photo: Carlos Santana, school picture, age 14, Tijuana, June 20, 1961.

You mentioned a great story about Stevie Ray Vaughan and Albert King. Albert told Stevie that he owed him $50,000 for copying his style – and Stevie paid it.

“Allegedly, yes.

What would you have done if somebody said the same thing to you?

“Oh, well, I do! I do it a few times a year for the last 10 years. Otis Rush. I send him a check two or three times a year. When I play Black Magic Woman, it’s All Your Love.”

Bill Graham looms large in the book. A tough man, but he loved musicians.

“Oh, absolutely. With me, Bill was very careful not to chew my head off. Only one time he did it because we were late. We weren’t the Santana we would yet become – we were in the embryonic stage. I didn’t know how to drive, so the people who had to drive us to the gig were really, really late. Bill was angry about that, but it was only the one time. Other than that, he was very careful never to insult me or hurt my feelings.”

You describe Santana the band as a mutt, not a purebred. But really, isn’t that the best way for a band to be, not so monochromatic?

“That’s true. You know, I love The Doors because they sound like John Lee Hooker, John Coltrane and everything in-between. They can sound like almost anything. Sometimes when you become a slave to tradition, then you sound like rubber-stamped music, and that’s not very interesting. I like cut and shoot music."

"Cut and shoot music"?

“Yeah, you know what that is? If they don’t like you, they cut you and shoot you – there you go. [Laughs] That’s John Lee Hooker. He’s the king of that music. You have to go to the other side of the tracks, where even black people are afraid to go. Bonnie Raitt can go there. She doesn’t have any fear. There’s not a lot of musicians I know who can go to the other side and get it and bring it back with them. Bonnie Raitt is one of them.”

You write at length about Miles Davis. Was that a difficult friendship at times? He wasn’t always the easiest guy to get along with

“Not with me. I never had a difficult time with Miles Davis. He would call me at two, three o’clock in the morning – [gravelly voice] ‘Hey, how you doin’? ‘Hey, Miles, great to hear your voice.’ ‘What are you doin, man’?’ ‘I’m learning and having fun.’ [Pause] ‘You’re always gonna be doin’ that, beause that’s the kind of mind you have.’ He was always very complimentary to me, just like Bill Graham and Clive Davis.

“I’m really blessed that 99.9 percent of all the musicians have been very supportive of me. Only a couple haven’t, and I don’t even wanna mention their names. And I think they were that way towards me because they were afraid. When you’re afraid, you act a certain way. When you’re not, then you embrace and you compliment.”

On Smooth

You detail some of the times you spent with Jimi Hendrix. Had he lived, do you think you two would have worked together?

“Oh, I'm sure of it. Jimi Hendrix was a person who expanded the perimeters of feedback and volume. Instead of watching a movie in black and white on a little screen, it became CinemaScope, multi-dimensional widescreen in 3D. Jimi Hendrix, more than anybody, created a new world of sound. Yeah, we would have worked together – absolutely. We were doing something that he was very interested in at the time – African rhythms. After he saw the band, he had a conga player.”

The '80s were a bit of a difficult time for you career-wise. When you signed with Davitt Sigerson to Polydor in the early ‘90s, did you think that was a new beginning?

“Yeah, Davitt! He’s a good man. It was a new beginning, pretty much. Davitt is a visionary, and he trusts that vision. The few people that I’ve met who are visionaries – Clive Davis, Chris Blackwell… You know, Chris let me go so I could do Supernatural. I owed him two or three albums. I said, ‘Your company isn’t equipped to deal with this, and I’m pregnant with a masterpiece.’ He let me go, which was amazing. There’s very few guys like that, the visionaries. Clive, Davitt Sigerson, Chris Blackwell – they want to take the art beyond the real of even what the artist can do. Bill Graham, too.”

A monumental man in your career has been Clive Davis. What were your thoughts when he proposed Supernatural to you?

“My thoughts were... discipline. Clive asked me, ‘Do you have the discipline, the willingness to implement discipline?’ He said, ‘On stage, Carlos, you’re incredible, but you need to take that energy to the radio.’ I said sure. It was about being more focused on the songs than the jams. Santana is more like Phish – we just jam. Sometimes you need a song.”

Did you have any idea that Smooth was going to be a hit? Not the giant hit that it was, just a kind-of hit?

“I didn't know Smooth would be a hit because I have no idea what a hit is. To this day, I couldn’t tell you. I just know that I trust Clive. When we did Smooth, when we did Maria Maria, and even when we did Black Magic Woman – I didn't know they would be hits. But I can tell you they felt incredible; I knew there was magic to them. Smooth is an amazing song. I think it’s only number two to Chubby Checkers’ The Twist.”

And Smooth is still winning Grammys. Aren’t you guys up again next year for some more?

[Laughs] ‘Yeah, man, something like that.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.