Brad Paisley talks Telecasters, recording, George Harrison and playing the UK

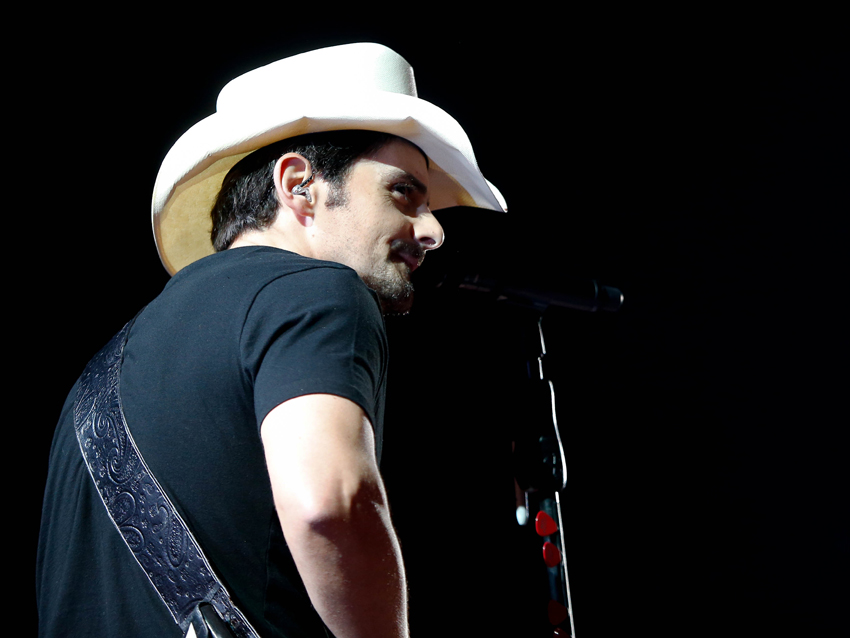

"I don't stand cool. I don't walk cool. But you put a guitar in my hand, and I own it."

Brad Paisley talks Telecasters, recording, George Harrison and playing the UK

Most touring musicians would object to doing a phoner at 8 a.m. And if they couldn’t get out of talking to a journalist at such an ungodly hour, they certainly wouldn’t be chipper. To those and plenty of other generalizations about superstar entertainers, Brad Paisley is the exception.

He couldn’t possibly have gotten much sleep between his arena encore and post-show VIP greeting the night before and a pre-sunrise wake-up call due to his kids being on the road with him. Even so, he turned on the talkative charm for MusicRadar and had no shortage of keen (and cute) things to say about his favorite Beatle, his faith in his road band and how his wallpapered axe gained cool quotient.

Paisley’s been a bona fide country headliner for the past decade, drawing sell-out crowds with some of the most forward-thinking honky-tonk tunes on the planet, the high-tech wit and flash of his live production and his dashingly tuneful Tele solos. He’s wrapping up a US tour promoting last year’s quirkily ambitious set Wheelhouse, which hit the road under the Beat This Summer moniker and was redubbed the Beat This Winter Tour when temperatures plunged, and is heading to the UK. As soon as Paisley gets back to the studio he built on his pastoral acreage in Franklin, Tennessee, he’ll resume the artful mixture of work and play that will lead to a new album.

Brad Paisley performs at the London O2 Arena on March 16th. Visit Paisley's official website for all dates and ticket information. A special UK Tour Edition of the album Wheelhouse, featuring a special bonus disc of 14 studio hits, is available here.

You’re about to return to London, this time to headline the second edition of the Country To Country festival. What’s helped you make inroads in the UK?

“I’ll tell you what helps over there – what I’ve found and what I think other artists need to understand – is that there is a hunger to hear us over there that I didn’t realize existed until I took the chance a few years ago.

“See, I went over in 2000 – or maybe it was ’99 – and opened shows for Reba [McEntire] on a festival she was doing there. She was headlining a festival, and then under her were Jo Dee Messina and Ricky Skaggs and me. I was on my first single. And it was a travel nightmare. I was green, and my team was green. It’s like, ‘Oh, this flight’ll do.’ You’re getting in too late and you didn’t have enough acclimation time. I remember going, ‘I ain’t ever doin’ this again.’ I even told my manager, ‘What am I doing over here? Nobody knows who I am in America yet.’ You know what I mean? And I didn’t go back. I was gone a long time.

“And then about four years ago now, we got a great invitation to go over. I started watching Top Gear and the British Office. I haven’t watched Downton Abbey yet, but all I hear is how great that’s supposed to be. And I believe it, because it’s an interesting culture. I relate, I guess, maybe because I’m Scottish.

“So I went over. And I was cautious. My promoter, Brian O’Connolly, said, ‘It’s gonna be a reality check for you. It’s gonna be humbling. You’re gonna have fun, but we’re gonna put you on sale at a place that’s gonna hold two thousand people. It’s gonna be half full. And the next time you come back, that one will be full. And the next time you come back, three or four thousand. You have to commit.’ And I’m like, ‘Okay, that’s cool.’

"What I didn’t realize is that I’d waited long enough and I’d gained enough following, and maybe the CMA Awards hosting and all that helped. Somehow, when they put that one on sale, it sold out – boom – right away. They put another one on sale. Sold out. They didn’t have any more available dates, or we could’ve sold out four of those. So we played those and had the best time ever."

Playing the UK

“[When I] played London again, they were gonna bump me up to, like, a mid-size venue. They did all this research – I don’t know how we do that sort of thing – and they came back and said, ‘You should play the 02 [Arena].’ And I was like, ‘What?!’ We put that on sale, and it did great… That’s been maybe two years ago. And now we’re going back again.

“This should be encouraging to any country artist that wants to go. It’s not like I have something all that special that they relate to over there or something. I tell ya, as a guy in a white cowboy hat, I’m exotic to them. I am the furthest thing from exotic in this land of the free and home of the brave. I am absolutely the poster child of ‘not exotic.’ And in England, I am an exotic delicacy.”

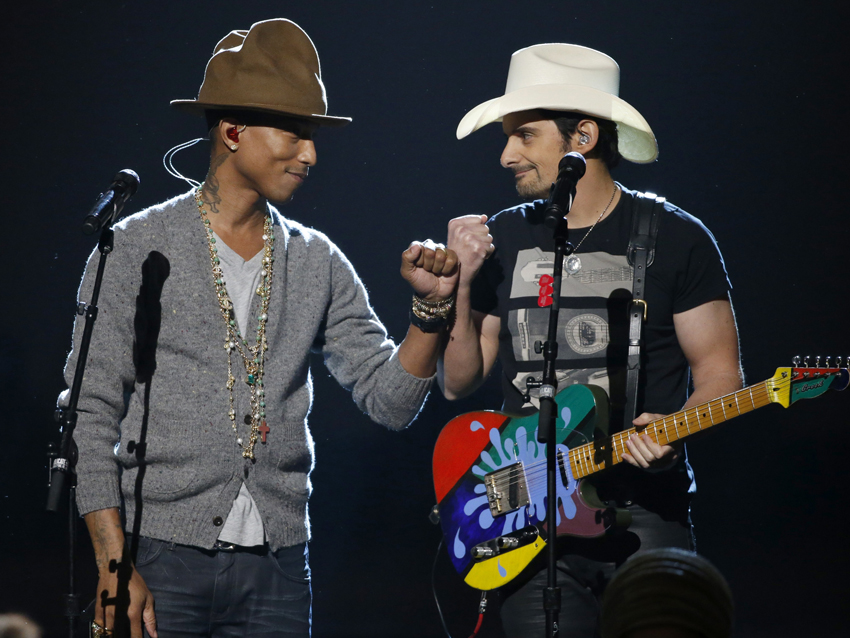

On the flipside, you just played a commemoration of the British Invasion of American popular music. You and Pharrell Williams performed Here Comes the Sun on a televised tribute to The Beatles coming to America. George Harrison was a very different style of guitar player than you are. Was there ever a time when you geeked out over The Beatles, and his playing specifically?

“Yeah. I was a later discoverer of them, because I came from a really country-influenced background. My mom and dad really liked The Beatles, I seem to remember. But I was raised on Buck Owens and George Jones.”

Well, Buck Owens could be a route to The Beatles.

“That actually is probably what got me headed in that direction – realizing their love of him. Once you discover The Beatles as a musician or a kid or a music fan, you dive in and it’s a phase you go through. You go through all of the various stages of The Beatles themselves.

“I had so many experiences the other night at that that I’ll never forget. I’ve gotten to know Ringo actually pretty well. I already knew him before I committed to this special, but I’d never met Paul till the other night."

The Beatles and George Harrison

“George Harrison was the one I identified with as this guy who was kind of the guitar player of the group, really… He’s this guy who sat around and would wait on his moment, and [whip out] Something. Or Here Comes The Sun. Or While My Guitar Gently Weeps… I saw Olivia Harrison. She walked up to me backstage and said, ‘That was wonderful.’ And I said, Your husband was my favorite Beatle.’ And she said, ‘Mine too.’”

Speaking of Buck Owens, you’ve pointed out how rare it’s been for a country instrumental to become a hit since his heyday. Did you face an uphill battle when you made your instrumental-heavy album Play? Did the label look at it as a time-out from the hit-making albums that you’d been delivering?

“No, they were great. I made a Christmas album and had a really good time doing that. It was like, ‘This is kinda fun making a thing that’s not just single, single, single.’ I felt like it’d be kinda fun to do the same thing [again]. But then I also realized, ‘If I’m gonna do this, I need to put a few things on here that are, possibly, commercial. They don’t all have to not have words.’ Because my fans don’t want that, either.

“By the way, it only takes going into some guitar jam night at a bar, where a bunch of guitar players get up and play, to realize we really need songs. [Laughs] These licks, they’re just not enough. You know what I mean?

“I wanted an album that was heavy on the guitar parts, and that’s what this was… I remember [then-label head] Joe Galante looking at me the moment I said I want to make a guitar album, a largely instrumental album. He went, ‘Oh, that’ll be great… We’ll pay for it and all that, but it can’t count towards however many albums you have left.’ I said, ‘That’s fine. As long as you pay for it, I don’t care. It doesn’t have to check a box off or anything.’ I think it was an important [project]. It’s always a hard thing to connect that dot, where people outside our format understand I can play. All those things help.”

I talked with Vince Gill about that not long ago – when you’re having radio hits, you’re bound to be better known for the singing than the playing. Still, you’ve featured your playing as much as possible between that album and instrumental cuts on other albums, plus the way you incorporate soloing into your live shows and serving as guest guitarist in other settings.

“My wife [Kimberly Williams-Paisley], who is not musically inclined, really, is most jealous of the language that I speak that she doesn’t speak… where me and Redd Volkaert or me and Keith Urban or whoever, we can sit down and start playing. It starts with this friendly little trying to one up each other, in a good way: ‘I’ll answer that with this.’ And you’re just talking back and forth on these instruments. She’s like, 'I just envy that.' And she’s seen it before where I’m a complete awkward fish out of water in a lot of situations, until this moment where they hand you a guitar and say, ‘Do you want to sit in?’ Then I can hold that conversation really well.”

Recording with his band

Like that Killers show when Brandon Flowers introduced you as “the Sheriff of Nashville.”

“I’m such a fan of [The Killers] that I just was going to the show. That’s a good example of a door that’s opened because of playing and wouldn’t be there otherwise. Basically, they were coming to town, and I called my booking agent and said, ‘I’d really like to go. I’m not asking to meet them. I don’t even really want to meet them. I don’t want to know what they’re really like. I just wanna hear them play.’

“The next thing you know, it’s four o’clock on that day, and I get a call and it’s my agent saying, ‘They want you to play a song.’ I got there and they were like, ‘Do you wanna play From Here On Out? It’s on the new album.’ I said, ‘Yeah, that’s fine. I’m that big a fan, I don’t even have to practice it.’ We sat down backstage and jammed for a little while. Then I went out and watched the show, and walked out and played with them. And then I went back out and sat with [my wife]. She’s like, ‘How do you do that? How do you just walk up there and play?’ I said, ‘That’s music. That’s the fun part.’ I bet she could jump into a scene and improv if she had to.”

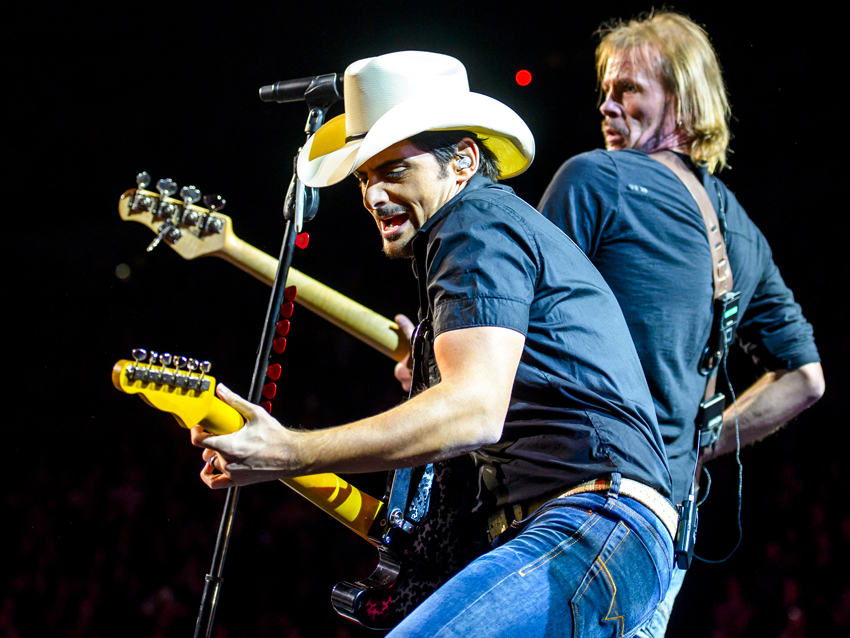

When it comes to your main gig, you bring the same players into the studio that you use on tour, and that goes for last year’s Wheelhouse. Recording with the road band is something most major-label country acts don’t do. What difference has doing it made for you?

“What you’re hearing on this latest record is the rawest form my band has ever been on tape. We didn’t really edit much. We replayed more than we fixed. I like making rules for each record. That album, the rule was it can’t be something you’ve already heard done. And no fixes. So that was a tough record.

“We’re in the process now of recording the next album – and doing it completely differently, while having learned from the last one as well. It’s an interesting thing when you do that with a band, because you bond in ways you could never bond before. They aren’t just hired for the road. They know that. They have an investment in this music. They are playing their own licks.

“No one honestly cares in the audience about that in our format, necessarily. Our odd drummer, guitar player fan might care: ‘Hey, that’s Ben Sesar on the drums. He’s played every record.’ But for the most part, the rest of ‘em are just there to hear these songs that they know. But that’s a really big deal to me. I take that very seriously, because that’s how I would want it done.

"If I hadn’t made it as a recording artist and was in my fallback career of being a guitar player/songwriter in this town, which is probably what I would’ve ended up doing somehow, and I got a gig with some kid that had hits, I would be really appreciative, would be very, very thankful to get to play on that album. My guys are good enough to do that, and they should. It’s a real thrill for us to do that. And actually, we learned enough last time that it’s become so much more fun this time, and less stressful.”

The joys of home studio recording

You already had such a highly developed sense of what guitar gear to use, like your boutique Trainwreck amps, and how to get what you want out of it. But producing on your own, without longtime producer Frank Rogers, was new to you, as was working with Pro Tools. Did you find it at all limiting, or was it the opposite?

“It was limiting for a little while, but it was also very inspiring. It made the first part of recording that album a horrible, stressful time. I wouldn’t trade any of the things I learned for anything, but it was very hard. This time isn’t like that, because now the learning curve’s gone. One thing I realized in that process is I don’t like producing. It’s not fun to me. I don’t like being in charge of that. So I’m not doing it that way this time.

“Frank is involved. He’s not co-producing. He’s basically, for a lack of a better word, I’d call him ‘executive producer’ at this point, because he has other projects as well, but he stops in. And then I’m co-producing with Luke Wooten, who is one of my best buddies and mixed the last couple records, basically. Co-producing is a whole different thing – it’s better.

“I love the aspects of writing and playing, and I’ve always been hands-on. But you know what? It was really important to do last time. Those things I learned were things I needed to know.”

Are you making the album in your studio again?

“Yeah.”

Last year, you mentioned that you relished not only the fact that you don’t have to pay by the hour when you record at your own place, but also that you’re recording a physical space that hasn’t been recorded before.

“Oh, yeah. It was duct-taped together for the last album. It was like those scenes in World War II where they’re taping things on the bombers and going, ‘Take off!’ This time it’s a whole different thing. We’ve had a whole other year of tweaking it and getting to know it even better. It’s great now – it’s a wonderful space.

“I brought in Luke and said, ‘Here’s what I’m thinking, and here’s what Frank’s thinking his role will be. I need a partner in this. I need your input. I need your song advice. I need your sound advice. I need your production advice, your arrangement advice, all that.’ And Luke goes, ‘I don’t ever have to set the drums up. I don’t have to figure out how to mic the drums. This is unbelievable.’ Because once you mic it, once things are sitting there, it’s such a sweet process.”

The visual appeal of the guitar

At this point in your recording and performing career, do you feel like you’ve developed just as recognizable a voice on your guitar as you have as a singer?

“Well, to some. To fans of [guitar], I think so. To other Telecaster players, any guitar players that are familiar with me, I think so. I think they would know me without a [vocal] on it. I think even fans of country music in general might go, ‘That sounds like him.’ That’s always been important, in my mind, that I have a style.

“A lot of people just set out to play as well as they can, but I really set out from day one, when I got that record deal and everything, to have a style. And I think, at some point, I wound up with one. There are great chameleon guitar players out there that can play anything and specialize in maybe not having a style. That’s actually an art form, too. But I didn’t have any interest in that, especially once I got a record deal.

“I’m ripping off John Jorgenson and James Burton and, in some ways, Steve Wariner and Vince Gill. My style is just essentially, I’m a thief. [Laughs] But that’s all anybody ever is – even The Beatles. I mean, even as inventive as they were, they are a product of Chuck Berry and Buck Owens and people that they liked.”

I saw John Jorgenson play the Station Inn in Nashville last year, and I seem to recall that your wife was at that show.

“Yeah, she went! I wasn’t in town… I was jealous she got to go to that. A couple of weeks later we were playing in California and I called [John]. I said, ‘I will swing down and pick you up if you’ll just be in the band tonight.’ And he came and played in the band that whole night with us. That was fantasy camp for me. And I’ve done that with guitar players that are heroes of mine, where they come and I just stick them in the band. I’m like, ‘I’m gonna play a solo on something and I’m gonna point, and you’re gonna take it, and I’m gonna watch you.’”

Ever since Who Needs Pictures, you’ve always been holding a guitar in album cover photos – or in the case of Wheelhouse, leaping over guitars. Did you decide early on that that should be a part of your visual representation?

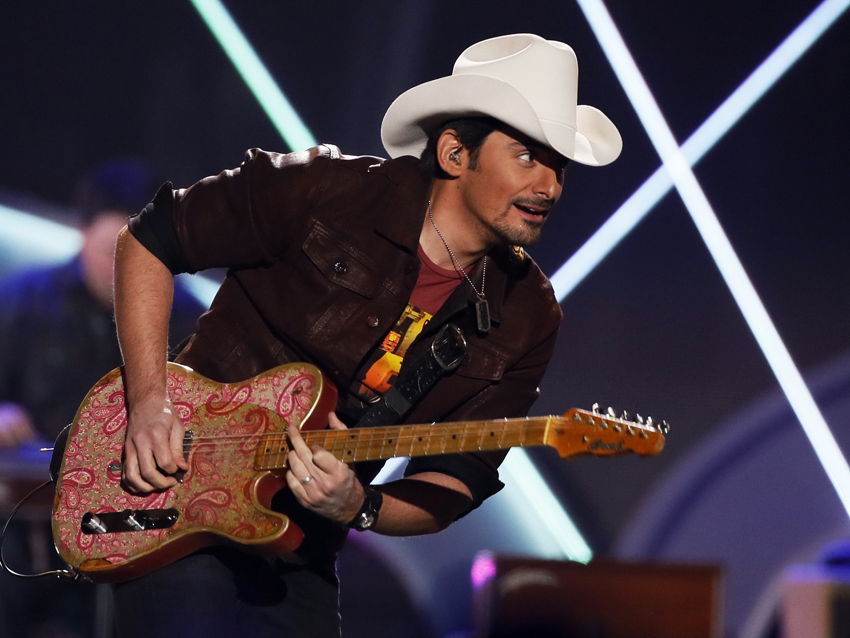

“I think it’s an essential part of sonically who I am, as well as should be visually. I think when you present yourself, you should think about what you’re saying with what you’re holding and wearing and all that. I think that my face is not as essential as two elements to recognizing me quickly image-wise: it’s this stance with a hat and a Telecaster. You know what I’m saying? You could stick somebody in that outfit, that’s holding a Tele a certain way, with a white hat, and people are just gonna think that’s me.

"And I think that’s probably good, in the sense that it’s sort of who I am: I sing country music, and I play the leads. It never feels right to me to see just a photo of me standing there. I look like a goober without a guitar. If I’m just standing there, I don’t stand cool. I don’t walk cool. But you put a guitar in my hand, and I own it.”

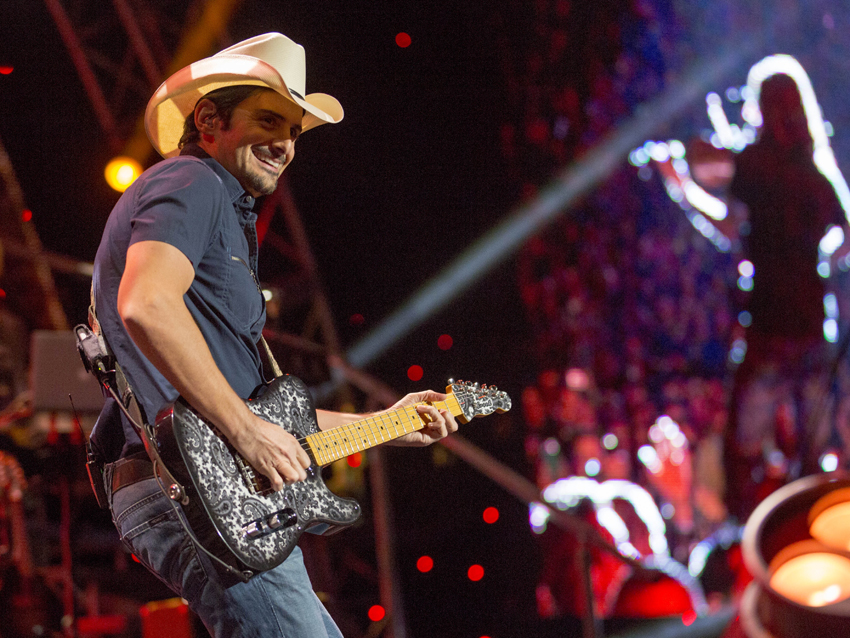

On the paisley Tele

Your association with a specific guitar, your 1968 paisley Telecaster, is pretty iconic at this point.

“I’m really lucky that James Burton made that cool. In 1968, Fender decides to make this ugly guitar, that would still be considered the worst decision in guitar finish history, [except for] James Burton… They were selling those very, very slowly. They only made about three or four hundred of ‘em, I think, with wallpaper stuck to the front. They thought, ‘This will get the hippies!’ [Laughs] And what happened was…[music stores] couldn’t sell it. They’d mark it down, some guy would buy it and he’d strip the wallpaper off of it and paint it. So there’s very few left, and they go for, like, 20 grand now.

“James Burton, almost as a joke, gets it sent to him by Fender. He opens it up and he goes, ‘I’m gonna play this tonight, and Elvis is gonna hate this, but it’ll be funny.’ He’s playing on stage and Elvis is standing there in Vegas, in his jumpsuit or whatever, and looks over and sees this thing. He gives him a look. And James is like, ‘Oh, crap. I’m getting fired.’

“Elvis never stopped looking at it and talking about it onstage. James got done with the show and just went straight to him: ‘I’m sorry, boss. I won’t ever do that again. I just thought it’d be funny.’ And Elvis is like, ‘No. You’re playing that every night.’ …He never played another show with Elvis that wasn’t with that guitar. And so that’s cool. Before that, it’s sort of like Joan Baez threw up on it.”

How did your relationship with that guitar begin?

“I bought that guitar in ’95. I’d always wanted one, but they had already gone up a lot. They’d already escalated because of James Burton. They’d gone from this awful stepchild guitar to, ‘Oh, that’s collectible.’ Sometime around college, I got enough money from a publishing/production thing with EMI, and I went and bought it. Found one at a guitar show in Dallas and bought that guitar, and that’s the only one I have. Everybody thinks I must have several of those, but I only have one. I have several remakes that I carry with me, but the only Fender paisley Tele that I have is that one. You know, I got a guitar builder to build ‘em in different colors now. It’s such a cool thing now to have a paisley finish.

“Everybody always said to me, ‘You need a paisley Tele.’ If my name was Sunburst, I’d have to play those or whatever.”