Booker White's 1933 National Duolian Resonator - in pictures

The story behind a gift and a friendship

The story

How did a guitar owned by Booker White, one of history’s most influential bluesmen and an early inspiration to BB King, come to rest thousands of miles away in the North East of England? We meet its current guardian, photographer Keith Perry, to find out how an unlikely friendship carried this iconic instrument all the way from Memphis to Newcastle.

The letter, written in a flowing hand on fading yellow notepaper, is dated 10 May 1976. Its contents may be brief, but mark an extraordinary moment.

“Mr Keith Perry, I am fine and hope you are. Most of all, I hope you have received the guitar by now and I hope you will like and enjoy it,” the letter read.

“You will have to tune it up, as I had to tune it down to send it. I will be looking to hear from you and [so] I will know if you got the guitar. Have a nice time in music and thanks a whole lot and let me continue to hear from you and Hard Rock.”

The words are those of Booker ‘Bukka’ White, the legendary Delta bluesman whose slide playing inspired the young BB King to take up guitar. They were written to Newcastle photographer Keith Perry, who has carefully preserved the letter to this day.

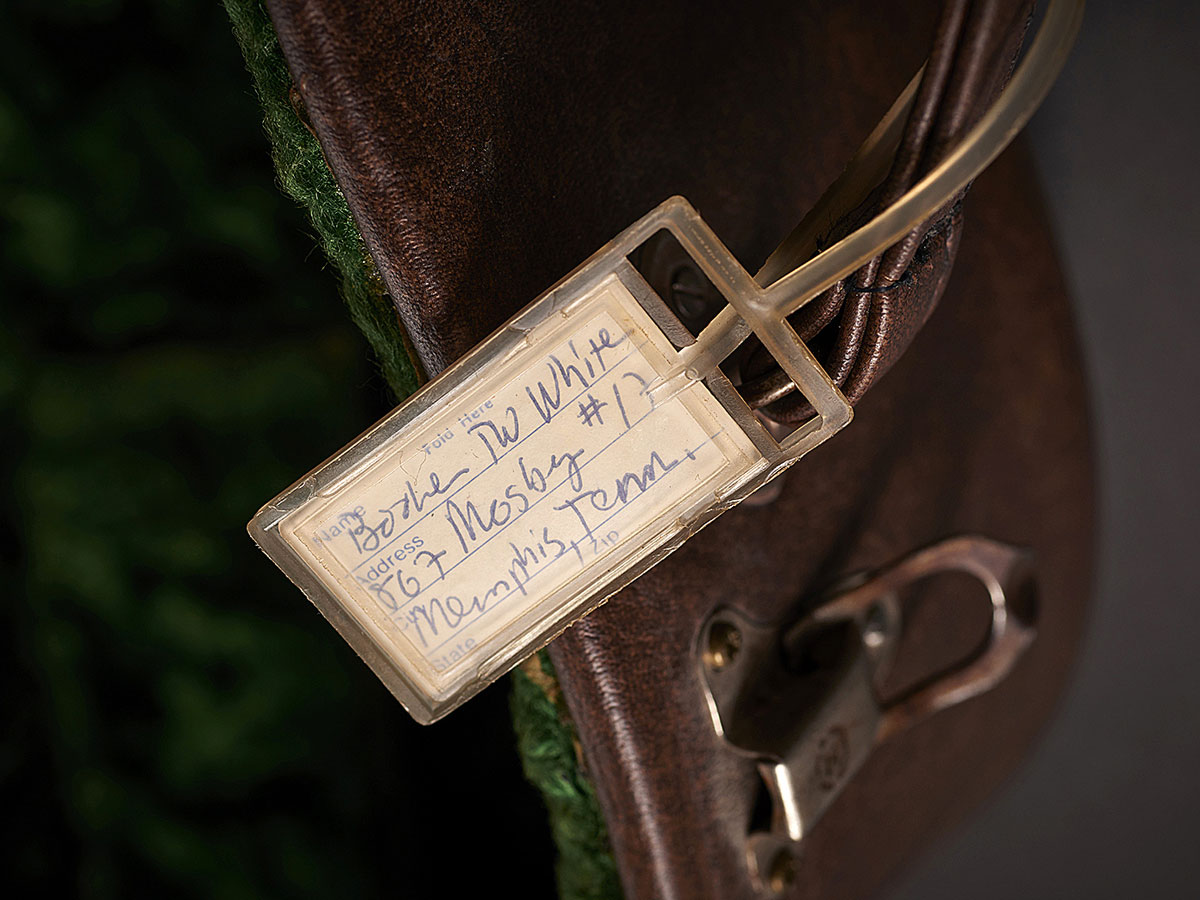

And little wonder, because Booker sent the note to confirm that his guitar, a 1933 National Duolian resonator that he affectionately called ‘Hard Rock’, had arrived at Keith’s home. This was not the result of some reluctant sale, but a remarkable gift made in honour of the unlikely friendship between these two men from vastly different backgrounds.

"He said, ‘Look, you’ve sent me tapes, you’ve been a friend. If you send me a couple of hundred dollars for the postage and you can have my old guitar’"

Booker White was one of the great Delta blues guitarists, who wrote songs such as Fixin’ To Die Blues, later covered by Bob Dylan, and Po’ Boy that powerfully evoke the hard lives and soul-piercing musicality of black bluesmen in America’s Deep South during the 1930s.

By contrast, Keith Perry was a press photographer from Newcastle - where he continues to live and work today. They met when a lost generation of great American blues guitarists discovered an enthusiastic fanbase in Britain during the 60s, reviving their music and their fortunes in a new land. With a Rolleiflex roll-film camera in hand, Keith Perry documented the shows these players gave to packed auditoriums around Britain.

“These guys weren’t appreciated back home, they were playing in folk clubs, wherever they could get work,” Keith recalls. “But they came over here and they got huge audiences. The reason they started touring was because [Piedmont blues guitarist] Brownie McGhee went to see Big Bill Broonzy in hospital. He was dying of throat cancer at the time and he said to Brownie: ‘You’ve got to keep this European touring thing going. There’s a great audience over there.’ So Sonny and Brownie, to fill the void, started touring with Chris Barber. And, of course, they were selling out everywhere. It was incredible.”

Captivated by the music, Keith found himself photographing and, later, becoming friends with some of these heroes of the blues, as they passed through the North of England on tour.

“Over time, I got to know many of them really well,” Keith explains. “Brownie McGhee was a superb guitarist and he came over with the American Blues Festival again in the mid-60s. But this time he was with Booker White and Son House. I met Brownie at the stage door and he said, ‘I want you to come and meet a real legend of the blues.’

“And that was the first time I ever saw Booker White, who was sprawled on a piano stool. There was a friendly handshake and I just sat and chatted. I was in absolute awe. This was a guy who’d seen Charlie Patton, and was inspired by him. Son House was in another room at the time and he was a link to Robert Johnson. So, I took a few photographs and then they moved on, touring again.”

On The Line

The story might have ended there, but for a chance conversation with Brownie McGhee that inspired Keith to get back in touch with Booker White a little later.

“A couple of years later, Brownie was across [in the UK] again - they came across quite regularly - and he said, ‘Have you heard anything more from Bukka?’ I said, ‘No,’ and he says, ‘Why don’t you write to him and send him some photographs?’ Brownie had this huge book: everybody who was anybody in the blues was in this book and he had an address for Booker.

“So I put a few photographs together and sent him a letter. I got a letter straight back thanking me, which I still have. I was astonished, but enclosed with the letter was a phone number, so I thought, ‘Well, why not phone him from time to time?’

“So I called him and he was over the moon that I’d actually phoned him in Memphis. So I said, ‘Have you got any of your old records?’ and he said, ‘No.’ He didn’t have any of them, which was quite amazing really.

"He told me how he watched Charlie Patton and how Patton not only played the guitar, but put it on the floor and danced on its back"

“So I said, ‘Right, I’ve got a couple of LPs.’ And so I sent him over a tape of all his early recordings and again he sent another letter back, saying how happy he was to receive the tape, and that he had sat up to the early hours listening to it and it brought back a lot of memories. So I kept phoning perhaps every three or four months.”

Soon the phone conversations became a regular fixture. Keith had a thirst to learn more about blues history and Booker had not only lived through those times but had recorded some of the most powerful blues guitar ever committed to vinyl. Thus Booker was able to give Keith unique insights into that world, recalled from direct experience.

“When I called, his wife used to say, ‘He’s in his office,‘” Keith recalls. “And you could hear him huffing and puffing on the stairs. His office was a seat just round the next block and he used to sit there all day drinking whisky and playing his guitar and fans would come by and chat to him, but that was ‘the office’.

“He just sat there all day talking to people. But as soon as I phoned, he was straight up the stairs. We’d talk about all sorts: the old days, the blues. Brownie McGhee was very much influenced by him. He loved his playing.

“I once asked Booker, ‘Did you ever come across Robert Johnson?’ and he said, ‘No, I heard about him. He travelled in different circles to me. But the king of the Delta blues, for me, was always Charlie Patton.’

“He said some people had suggested that he’d never seen Patton. But Booker said, ‘No, I definitely saw Charlie Patton.’ He told me how he watched him and how Patton not only played the guitar, but put it on the floor and danced on its back.”

The story (continued)

The hard times, of course, were etched just as starkly in Booker’s memory as the good. His famous song Parchman Farm Blues refers to the severe privations he experienced as an inmate of Mississippi State Penitentiary, after being jailed in 1937 for killing a man during a bar-room altercation. Booker always maintained it was an act of self-defence, but the memory of it was not something he chose to dwell on, Keith says.

"I can’t imagine some of the scrapes he must have been in in Mississippi"

“I asked him once about the murder rap and he was a bit evasive about it. He just said, ‘If I hadn’t have shot the man, he would have shot me.’ But he’d had a hard, hard life, hadn’t he? I can’t imagine some of the scrapes he must have been in in Mississippi. It was a very violent place.”

Booker and Keith’s correspondence continued in this way for many years until one day, just a few months before he died, Booker did something remarkable.

Apparently on impulse, he offered to give Keith his National Duolian resonator, which he affectionately called Hard Rock and which had been a companion for much of his eventful life.

“There was one phone call I made to him and I said, ‘I’d love to get a hold of a guitar, a National, like yours.’ Because you never saw them for sale in this country,” Keith recalls, clearly still awed by the gesture.

“And he said, ‘Look, you’ve sent me tapes, you’ve been a friend... if you send me a couple of hundred dollars for the postage and packing you can have my old guitar.”

And of course, I was completely blown away. “I was a bit strapped for cash at the time, because I’d just bought a house,” Keith adds. “But I had a word with my bank manager, and he said, ‘Yes, we’ll arrange something.’”

A few weeks later, Keith got a call from Customs officials at Newcastle airport, to whom he duly delivered the princely sum of £17 in import duty that had to be paid before the irreplaceable guitar was allowed into the country, as Keith recalls. “I said, ‘By all means, yes, that seems very fair.’ I couldn’t get out of that airport quick enough.”

National Treasure

The following February, Booker died of cancer at the age of 67 at his home in Memphis. And while Keith mourned the loss of a player who had been first a hero and then a friend, he resolved not to shut the guitar away but put it into the hands of musicians whom he felt would appreciate its true value, including Mark Knopfler, Don McLean and one of Keith’s first guitar heroes, Lonnie Donegan.

"As soon as BB saw that guitar, he kissed it. That’s what he was like"

On one special occasion, he showed Hard Rock to Booker’s cousin BB King at a hotel in Gateshead, who remembered it from the time when he lodged in Booker’s Memphis home, at the very outset of his own career in music.

“BB said he remembered it being kept on top of the wardrobe at his place in the 40s because he recognised the décor around the top straight away. As soon as BB saw that guitar, he kissed it. That’s what he was like.”

The magic of the guitar also bewitched latter-day bluesman Eric Bibb. He ended up recording a fine album, entitled Booker’s Guitar, with the instrument, which was loaned to him for the purpose by Keith. But as Keith recalls, it took a bit of nudging from his son before he decided to approach Eric with the guitar.

“Eric played a concert [in Newcastle] and he was signing CDs afterwards and so my son Richard said, ‘Mention the guitar to him.’ I said, ‘No, he’s one of the new generation, he won’t want to know.’ But as we got closer to him, my son insisted. He said, ‘Please, mention the guitar.’

“So we got there and Eric was signing away but I said, ‘Are you into the music of Booker White at all?’ and he said, ‘Yeah, I love Booker White’s music.’ I said, ‘Well, I’ve got his guitar at home, if you’d like to see it and play it before you leave town in the morning. I’ll bring it to wherever you’re staying.’ His glasses slid down his nose and he said, ‘You have Booker White’s guitar at home? I’ve got to see this.’ So he said, ‘Give me your phone number.’

“Sure enough, he rang at eight o’clock the next morning. ‘This is Eric. Can you bring the guitar? I’m at some hotel in Gateshead.’ So we shot straight over there because he was due to climb on the coach in about half an hour. He opened the case and he just said, ‘I feel a song coming on.’ And in fact, the first song he wrote was Tell Riley.

“Then he said, ‘I’m going to come back and record with this.’ And he did. He took a break from touring and he got the coach up here. He said, ‘It’s too valuable to send to me, so I’ll come there.’ So he hired a studio in Gateshead and I think he did about six takes. Eric Bibb is one of the nicest people you could work with,” Keith adds. “He’s become a good friend as well.”

It’s clear that there is some power of union in this instrument. It connected Keith, who has never visited America, with one of the greatest blues guitarists of the Mississippi Delta.

Today, he’s still making friends with musicians drawn to the guitar’s heritage - while Hard Rock is still being used to make sweet, soulful music. It’s hard to imagine its former owner being unhappy with that outcome.

Read more about the guitar and the life and music of Booker White in a new book, by Peter Daniels, who worked with Keith Perry to produce The Legend Of Booker’s Guitar, available from Lulu Press for £10.99

Fretboard

“Booker had huge hands and he used to slap the guitar at both ends of the neck, a technique that he called ‘spanking the baby’.

“It’s an incredible technique but Brownie McGhee said it was just to impress the ladies! He was a very strong, very powerful man,” Keith Perry recalls. The visible dents on the fretboard are probably the result of accidental hard knocks, however.

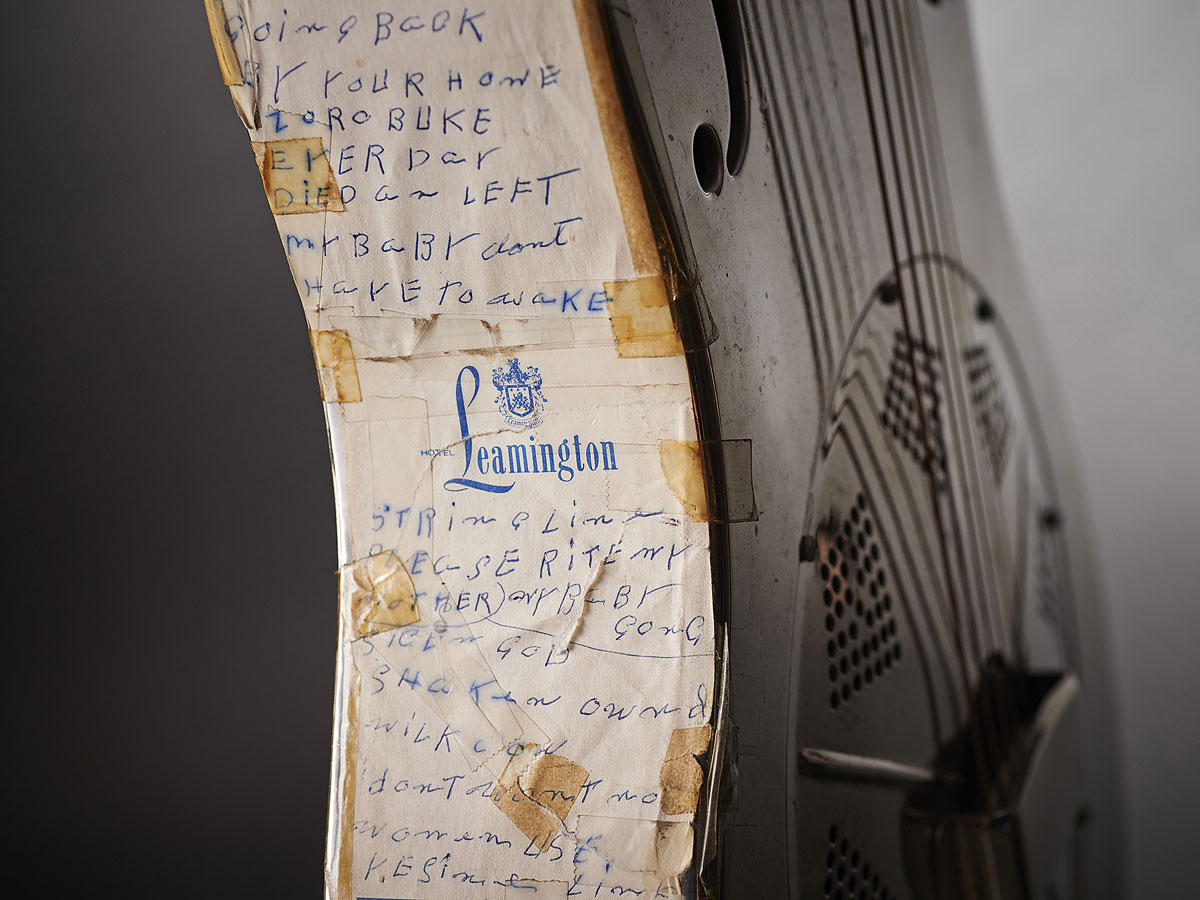

Setlist

“The guitar still has Booker’s setlist taped to one side. There’s some strange little augmentation on the top half.

“I’ve no idea what he put that there for - it obviously meant something to him,” comments Keith Perry. “You can make out the song titles of Gibson Hill and Aberdeen further down, though.”

Bridge

The guitar has been kept largely in its original condition, but some fettling has been done to ensure it can be played and enjoyed.

“Steve Philips made some adjustments to the bridge,” says Keith Perry. “That was quite a complex little job, because it was very uneven at the time. I think you can appreciate the hammering it has had over the years - but Steve evened out the action on the guitar and made it playable again.”

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.