Book excerpt: Sound Man by Glyn Johns

Having worked on some of the most seminal rock 'n' roll records of all time – albums by The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin and the Eagles, just to name a few – producer and engineer Glyn Johns not only witnessed a cultural zeitgeist; he was an active participant.

In his just published memoir Sound Man, Johns opens up about his life and career in the studio. In the excerpt from Chapter One below, he discusses how a stroke of luck led to him getting his foot in the door at London's prestigious IBC Studios. (You can order Sound Man: A Life Recording Hits with the Rolling Stones, the Who, Led Zeppelin, the Eagles, Eric Clapton, the Faces... at Amazon, Barnes & Noble and IndieBound.)

I left school in July of 1959, at the age of seventeen, not knowing what to do. I know knew that I didn’t want to work in an office or in any nine-to-five job. Agriculture interested me, but without substantial capital it seemed pointless to pursue as a career. It was about this time that two of my best pals, Rob Mayhew and Colin Golding, and I decided to form a group that I managed and was the sometime singer with, called The Presidents.

Well, it wasn’t exactly a group, more a random collection of guys playing things. It evolved out of the Gang and its insatiable need for cheap entertainment. We started out playing for our own amusement at each other’s parties. In its final configuration, without me singing, it became a really good cover band. We would rehearse each week, and I realize now that the experience of listening to and dissecting the popular records of the day in order to replicate them accurately with the band was excellent subliminal training for my future as an engineer and producer.

As the band became more popular, we decided to find a regular venue to play. We took a room at the back of the Red Lion pub in Sutton every other Friday. It was an instant success, and after paying the rent we would make £30 or £40 a night. Which in those days was a fortune.

I had been working in a department store on Saturdays for the previous year, so I took a full-time job there until my exam results came through and I could decide what to do. The results proved to be even worse than expected. I had taken eight subjects and passed only two, history and English literature. This came as a great disappointment to my parents, and gloom set in as they wondered what would become of me without the required academic qualifications for further education and therefore entry into any of the more recognized professions.

Out of the blue, my sister Sue came home from work one day and asked me if I would be interested in the idea of working at a recording studio. Her boss had a girlfriend, and while she was waiting in the outer office for him, Sue mentioned to her that she had a brother whose main interest in life was music. She responded by telling Sue that she owned a small record label that specialized in Welsh music and would try to get me an interview at the recording studio she used—that is, if I was interested. Needless to say, it had never entered my mind to work in the music business. I knew absolutely nothing about recording and had never thought about or known anyone working anywhere but in the usual and more mundane professions. So this opportunity came about only as a result of a polite conversation between two women who did not even know each other. I have often thought what an extraordinary turn of fate this was.

A good start

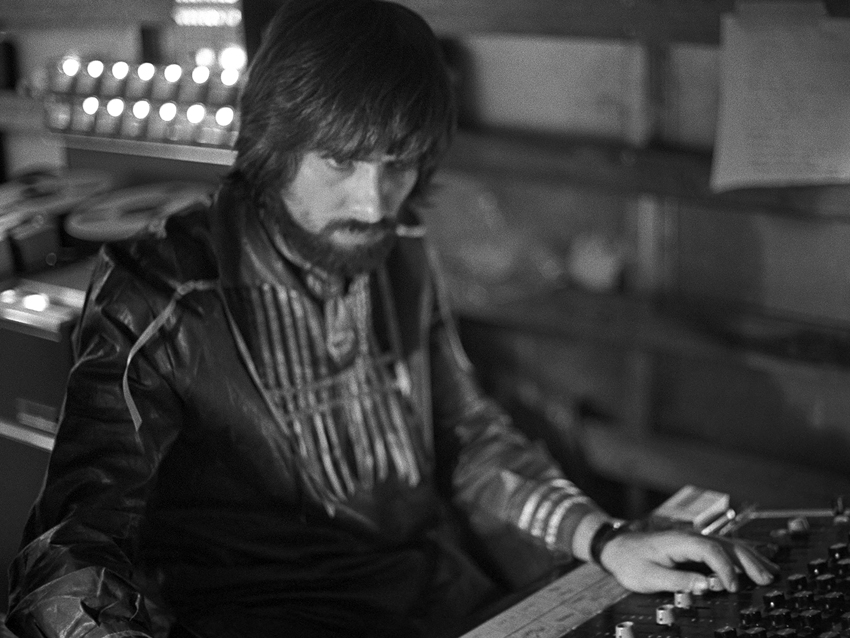

Above photo: Johns at IBC Studios, circa early '60s.

It was with great apprehension that I went for the interview a few days later. The studio turned out to be IBC in Portland Place, which was without a doubt the finest independent recording studio in Europe at that time. The manager, a seemingly pleasant Welshman named Alan Stagg, asked me a bunch of technical questions about re- cording, none of which I could answer. He said there was nothing available right then but the next time there was a vacancy he would certainly consider me for a job. The only thing that seemed to be in my favor, as I pondered the experience on the train back to Epsom, was the fact that I had a Welsh grandfather, a Welsh name, and that I’d had some formal training in a choir. God bless the Red Dragon!

I returned to my job at the store thinking I would probably never hear from the studio again. This would almost certainly be true if I had been left to my own devices. About six weeks had passed since the interview when my mother suggested to me that, as I had heard nothing, I should call Mr. Stagg and jog his memory. I argued, saying that, after all, the man had said that he would consider me at the next opportunity. Fortunately my mother insisted on my making the call, pointing out that I had nothing to lose. So I rang Alan Stagg, and having reminded him who I was, he said that one of the senior engineers at the studio had handed in his notice that day and that this would create a vacancy at the bottom of the ladder for a trainee, so when could I start? I am convinced that if I had not called that day I would never have heard from IBC again and would probably have not got involved in music as a career at all.

I started work at IBC the very next day, as a lowly assistant engineer. This meant setting up the studio before each session to the engineer’s requirements, keeping continuity, and taking the blame for anything that did not work, while receiving varying amounts of verbal abuse from my superiors before, during, and after the session, and then stripping the studio afterward, with a great deal of tea making and equipment polishing thrown in.

The first session I was assigned was for Lonnie Donegan. This was too good to be true. He was still my favorite recording artist. I even discovered that the picture on the front cover of my much-coveted 10-inch album was taken in studio B at IBC. It was all too much for a young boy.

IBC had no affiliation with any one label, being privately owned. In those days, RCA, Decca, Pye, and EMI all had their own studios, leaving the rest for the independents. As a result we had an incredible variety of artists, musicians, and clients passing through. The music ranged from the most idiotic jingles to big bands—from Julian Bream to Alma Cogan, the music for the CBS TV series Wagon Train to a modern jazz quintet, and the odd excursion out to record a symphony orchestra or pop concert in far-flung venues.

As my feet touched the ground again after the initial shock of getting the job, I realized that my primary objective at IBC should be that it would give me the opportunity to get my foot in the door and explore the music business with the view of being discovered as a singer. Although fascinated by the recording process, I was far more interested in music and those who made it. I quickly realized that the best thing to do was to work as efficiently as possible while keeping my head down, observing as much as I could to establish who did what, when, where, why, and to whom.

The system

In those days, record producers were called A&R men, meaning “artists and repertoire.” They all worked for a label and were responsible for the artists they were assigned or they brought to the label and for the repertoire of music those artists recorded. Very few singers wrote their own material, so the A&R men would select songs from the vast array that was pitched to them by the music publishers. This made them extremely powerful, with the potential to manipulate the situation to their own benefit. For example, they might have their own publishing company and increase their earning capacity by doing deals with other publishers to split the publishing of a song, or perhaps take the publishing of a B-side or album track in exchange for agreeing to record a song with a successful artist.

The A&R man would pick the song and, having routined it with the artist and chosen the correct key to perform it in, would decide on the arranger, who in turn would use a fixer to book the musicians. This would invariably be an older musician who acted as an agent and union representative for session musicians he booked. Sometimes the A&R man would be involved in the details of the arrangement and of the choice of musicians, sometimes not. Most A&R men had a favorite recording engineer they worked with and would very often choose a studio based on who worked there, as there were no freelance engineers then.

All of this would be done within the restrictions of a budget, which the A&R man would draw up and have approved by his superior in the company and thereafter be responsible for. He would then supervise the session, making sure that the engineer, arranger, musicians, and artist performed to his satisfaction. Hopefully making the song sound as he had envisaged. So it became apparent fairly quickly how important the engineer was to the success of a studio, both in personality and variety of musical taste as well as the more obvious technical and creative abilities.

IBC was not only the best-equipped independent studio in Europe but it was also blessed with a great assortment of engineering talent, starting with Eric Tomlinson, who was the senior engineer on the staff when I began and, in my opinion, was one of the finest in the world. I remember that he had this habit of standing with one foot on top of the other while he worked, his hands flying around the console, never needing more than one run-through of the most complex of orchestral pieces before having it memorized, balanced, and ready to record. He was extremely kind to me, and I learned a great deal from watching the master at work.

Then there was the very aptly named Ray Prickett. Although he suffered from little or no sense of humor and treated me like an unpleasant smell, he was still a great engineer. Among many others, he engineered most of the records that Alan Freeman produced for Pye Records. Petula Clark, Lonnie Donegan, and Kenny Ball being a few of the many successes he had. John Timperley, who was a little older than me, was another who developed his own approach to recording with great success and went on to have his own studio in London.

Then vs now

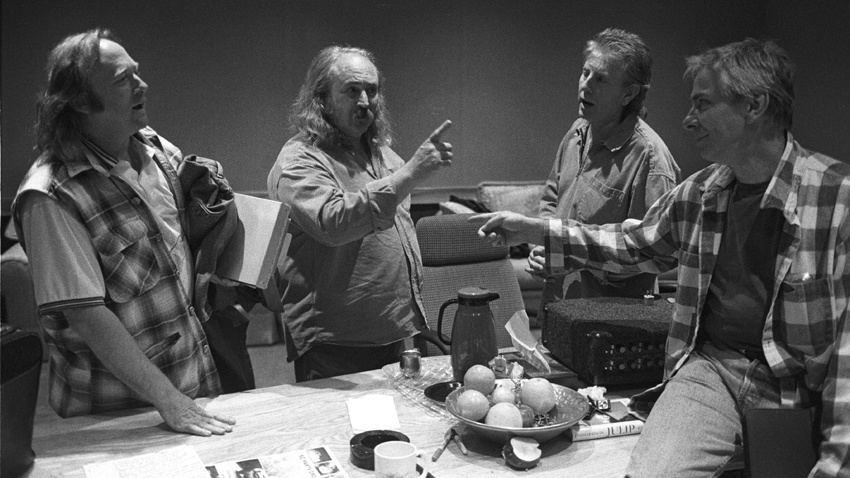

Above photo: Johns (right) with Stephen Stills, David Crosby and Graham Nash.

Alan Stagg was also an engineer, specializing in classical recording. IBC being the only independent studio in Europe that had its own mobile recording unit meant we could go to any of the bigger venues required for recording large orchestras and choirs. Alan did very little recording, which turned out to be a good thing, as it quickly became apparent to me that he was not much of a specialist. However, he made sure the studio was always the first with the latest equipment, and the fact that it had such a great variety of talented engineers must have, to a large extent, been down to him.

Some of the classical sessions were engineered by David Price, an unpleasant little shit of a man, as I remember. He had a client, a BBC radio producer in real life moonlighting as a classical record producer. He bordered on certifiable, and like so many producers was an egomaniac. Most of the classical stuff was done on location, in large halls in London that could accommodate a symphony orchestra, like Wandsworth, Hammersmith, or Walthamstow town hall.

Today, mobile recording units are purpose-built trucks. Back then, the equipment was loose in boxes. We would hire a furniture-removal van, load it up, then unload at the venue, where we would be allocated a room to use as a control room. This invariably would be a dressing room, chosen by some faceless individual who clearly didn’t want you there, based on the fact that the room was up several flights of stairs and as far away from the auditorium as possible. Having assembled the equipment in the control room, the engineer and his assistant would leave the tech to make sure that it worked and was aligned properly, while they ran the miles of cable to the auditorium, put up the microphones, and arranged the setup of the orchestra in the space available to them in the hall. All this to say that, by the time people started to arrive at the session for a ten-o’clock start, you had already done a full day’s work and were completely knackered.

This producer would arrive in the nick of time, throw down his briefcase containing the score, walk over to the loudspeakers, demand that they be turned flat out, and stick his ear right inside them. If he could detect the slightest hum or buzz, all hell would break loose.

I remember one such occasion: fourteen strings and a harpsichord at Red Lion Square in London. Not the most scintillating session I had ever been assigned to. The producer had thrown his usual wobbly, and David Price had blamed the poor unsuspecting tech. I had worked late the night before and, having had only two or three hours’ sleep, made the mistake of nodding off during a take, only to be awakened by a swift belt round the ear from David Price, with the producer doubtless applauding in the corner. Looking back, it is extraordinary what people got away with in those days. However, I never fell asleep during a session again.

The other major difference in the early days was that the maintenance department would be much larger and play a key role in the development of the studio, designing and building the consoles that we used in-house. This becoming a most important part of a studio’s reputation for being up-to-date with the latest technology. Nowadays it is equally important to stay abreast of the times; however, this is not achieved with the individuality that existed in the sixties, as nearly all recording equipment is now mass-produced and name-branded.

Late '50s/early '60s studio dress code

The late great Joe Meek used IBC on occasion. He had his own studio at home, where he developed his extraordinary sound, but he would often bring his tapes in to run them through one of our home-built equalizers to cheer them up a bit. I think he was frowned on by the powers that be, and as I was the most junior in the place I would be given the job of looking after him. What a great opportunity for me. He was a great and innovative engineer and a quiet, kind, and seemingly egoless man.

Last but not least was Terry Johnson. He left school illegally at fifteen and lied about his age to get the job at IBC. By the time I arrived he was already doing sessions as an engineer at sixteen. To say he was a natural is something of an understatement. He was an extraordinary talent. For eighteen months or so we were pretty much inseparable. We soon discovered that we shared the same taste in music and sound and became close friends, closing ranks against the somewhat disapproving attitude of the senior engineers at IBC.

As that first year progressed, music began to change and the demand increased for English records to sound more and more like what was going on in America. Most of the older engineers didn’t get it and were entirely dismissive. This meant that Terry, being as young as he was and having a natural enthusiasm for trying new ideas, was in great demand, and he pulled me along with him.

We were constantly being challenged on how to re-create sounds that were coming from America. This proved particularly difficult because American musicians were creating a very different sound and feel to the English guys, something I was to have illustrated in triplicate when we had the privilege of prerecording the music for a TV show with Dusty Springfield called The Sounds of Motown. They flew the band in from Motown and set up straight off the plane. We turned the mics on and instantly there it was. Just like the records we had been listening to. I remember Terry and me looking at each other with great relief, as we had imagined that we were in for a struggle, not knowing how the hell that sound was achieved.

We had to figure out new methods of recording to capture and do justice to the new, louder rock and roll as it took over. Previously, the loudest sound anyone had recorded was the cannon in the 1812 Overture.

The studio was a constant buzz of activity. In a normal day, both studios A and B would have three sessions, very often each having a different client, musicians, and artist. The whole approach to recording was so different then. Even the dress code: a jacket, collar, and tie for all engineers and assistants. White coats, collars, and ties for the technical department. Sessions lasted three hours when as many as four songs would be cut. So albums were very often cut in a day. The volume and variety of work was fantastic, the building being constantly flooded and drained of an extraordinary assortment of people, from the most colorful, extrovert artist to the most bland suburban string player, hurrying off to his next seven pounds ten shillings, wondering what was going to win the 2:30 at Sandown Park.

In the late fifties and early sixties almost everything was recorded in mono, as very few people had the facility to play stereo. The exception was the odd classical recording. Unlike today, it was all recorded at once, so when the three-hour session was finished, the tape could go straight to a cutting room to transfer the sound to disc and then on to the factory to be processed and pressed onto vinyl. If it was a single, and therefore did not require a sleeve with artwork, it could be in the shops in a few days. In fact, very few artists got to make an album in those days, as you had to have a few hits under your belt before it was justified. Then you were allowed to make an EP, finally graduating to ten or twelve cuts on an LP.

From the book SOUND MAN by Glyn Johns Copyright © 2014 by Glyn Johns. Reprinted by permission of Blue Rider Press, a member of Penguin Group LLC.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.