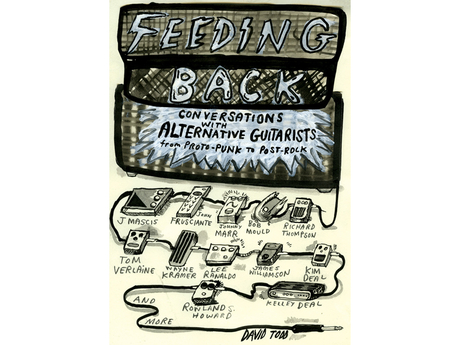

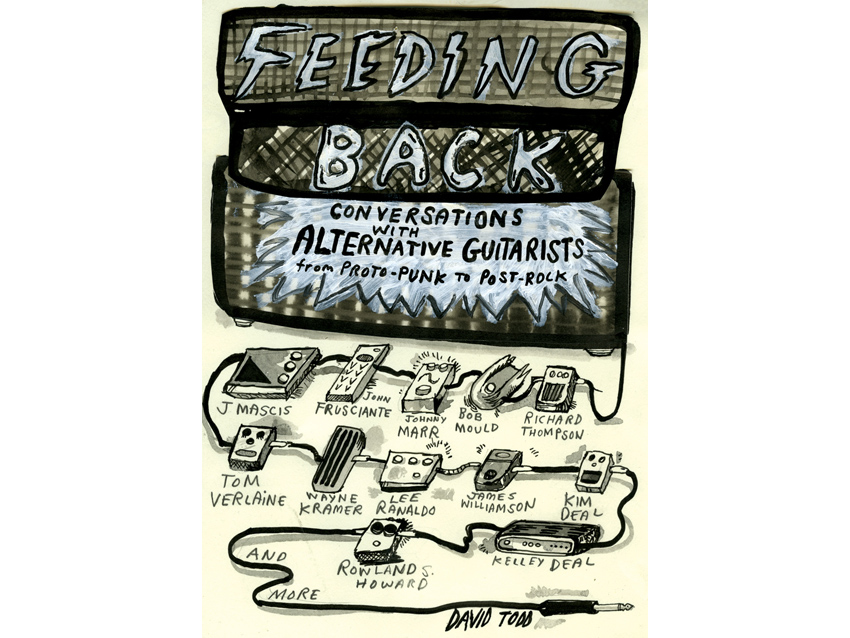

In the new book Feeding Back: Conversations with Alternative Guitarists from Proto-Punk to Post-Rock, author David Todd celebrates the wildly idiosyncratic skills and vital contributions of some of the most creative guitarists operating in the niche known as "alternative rock."

Over 25 artists are profiled in this captivating page-turner, including Richard Thompson, Lenny Kaye, Kim Deal, Kelly Deal, Johnny Marr, J Mascis and Fred Frith.

Feeding Back: Conversations with Alternative Guitarists from Proto-Punk to Post-Rock (Chicago Review Press) will be published in June in the US and July-August in the UK. It can be purchased at this location, and will also be on sale via Barnes & Noble, Amazon and US indies.

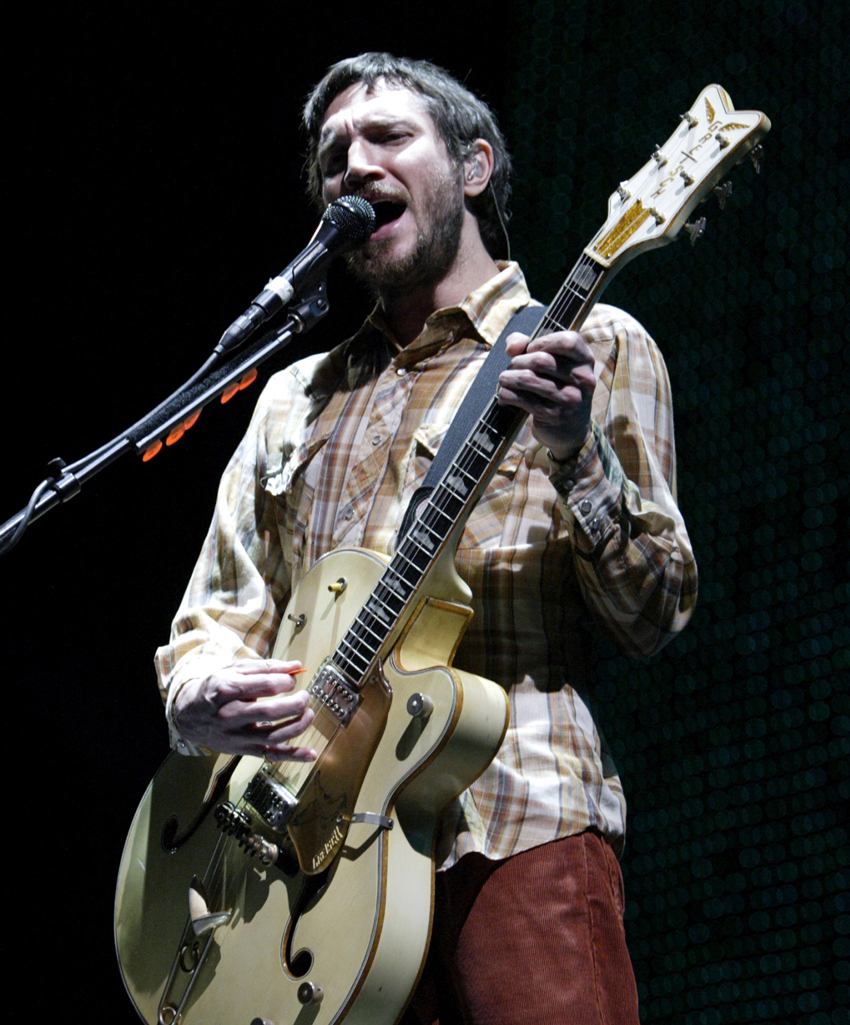

In a preview excerpt from Feeding Back, MusicRadar presents an interview Todd conducted with John Frusciante in June of 2009, six months before the guitarist announced his departure from the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

In the past, you've talked about guitar "antiheroes." What do you mean by that?

"Well, I grew up dedicated to the guitar, so I studied all the flashy players when I was kid. And I think I grew up with a misconception - which is pretty normal for a person who plays any instrument, but especially the guitar - where the physical action that's taking place on the instrument seems to count for something more than it should.

"It's such a complex thing, making music, and I feel like when flashy guitar players get really good, a lot of the time they lose sight of the fact that really slow notes and really simple notes, just because they fall in strange places, can create various types of space with the other instruments.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"People have the tricks that they do - they have their little techniques and riffs - and they forget about trying to shape music into something that depicts an energetic picture, a picture in sound that arouses all these feelings inside you. With the flashy guitar players, it becomes more about demonstrating something.

"So, you know, I lost interest in that as a teenager, and I became fascinated by people like the guitarist from the B-52's [Ricky Wilson]. I started to find more meaning in people who played simpler, because these people seemed to have a better grasp on the complexities of that, you know. A lot of people who are really good technically don't give that same kind of care to each note."

"People fall into patterns at fast speeds, when really to have a clear musical thought - the kind of musical thought that makes a melody work - our brains just can't think that fast. At a certain point, you're going on automatic. When it comes down to it, when I hear somebody playing really fast, to my mind it doesn't sound complicated at all, and what somebody like Matthew Ashman in Bow Wow Wow or Bernard Sumner in Joy Division is doing sounds complex, because each note pulls you in a different direction.

"I like all kinds of guitar players, but it's people like the ones I just mentioned whose playing really amazes me, and it's because of their ideas, it's because of what they thought. It's because they approached the instrument differently than anybody else. It's people like Keith Levene from Public Image and Daniel Ash in Bauhaus who are exploring the possibilities of what you can do with the guitar, whereas other people seem like they're just exploring what you can physically do, and that serves no interest to me anymore. It did when I was 15 [laughs], but not anymore. Not since I was 21 years old."

What happened when you were 21?

"That was when I first started to really find myself as a guitar player, because a lot of things happened to me on the same day, and a lot of them had to do with me as a human being and my philosophy switching poles. I went through this change as a person, and I went through a musical change, too. Obviously, I'd been moving towards it, but I remember clearly the main part happened in like one day, you know?"

What were you listening to then?

"Tom Verlaine. I remember listening to [Television's] Marquee Moon and being dazzled by it. What he did with a sort of jaggedy guitar sound, the amount of beauty and expressiveness that came out of it, was really exciting for me.

"It made me remember that none of those things that are happening in the physical dimension mean anything, whether it's what kind of guitar you play or how your amp's set up. It's just ideas, you know, emotion. I'd grown up thinking, 'Well, a guitar player should be a good balance between technique and emotion,' and I just realized, that's ridiculous. It's only emotion, it's only color.

"And it took me like eight years of being really devoted to the guitar to realize that. [laughs] I kind of knew it when I started and then I gradually forgot it, and then when I realized it again, it hit me like a ton of bricks."

Frusciante plays a favored 1957 Gretsch White Falcon with the Red Hot Chili Peppers, 2007. © Robert James Wallace/Reuters/Corbis

In general, the antihero types may be more instinct driven, with less theory than someone like you. Do you think that period when you were 21 was when your instinct and theory came together?

"Yeah. At the time, I thought it was because I wasn't thinking too much in terms of theory anymore - but I was. It was just that it was so… like the point of my first solo record, in my mind I was just throwing everything out the window. I was throwing all theory and technique out. But then after that, when I hadn't played guitar much for about four years, my playing felt quite different. Without that technique, I didn't know how to twist it as well.

"I don't have an extensive background in theory, but the amount of it that I've learned, I've applied, so I have a vocabulary of melodic and rhythmic relationships. And that's all theory is - it's symbols to help you identify those relationships. To some degree, somebody can perceive them just by playing the guitar a lot and seeing them in terms of shapes on the neck. But I notice that with those people, a lot of the time they have to fiddle around for a while to find a part.

"If guitar players don't know the modes, for instance, it takes them a while to figure out which notes they can play, whereas somebody who's practiced those scales knows immediately what notes apply. So for me, theory has always opened things up to where I can walk into a room and just by hearing something I know exactly where to go on the guitar. I have a better time playing because I have a variety of colors to bring to the table.

"To me, it kind of makes sense that so many people end up resorting to the physical part of guitar playing. People want to do something that they can conceive of, you know? Like, 'Oh, I'll practice scales all day and I'll be able to play really fast and impress people.' It's a real cut-and-dried, straight-ahead way to learn something.

"But when you start really boggling your mind with what can make something that's as simple as a Beatles song - when you actually examine it lyrically, rhythmically, and melodically, and chordally - something very complex, in some way an understanding of that is less intimidating, you know? To me, the only thing that makes music not intimidating is the ability to take it apart."

You say that you haven't studied theory extensively, but compared to most rock musicians, you break things down easily. Although it's obvious how much of your playing comes from an internal place, does this theoretical knowledge ever lead you toward more of a formalist approach?

"No, for me to enjoy making music, it has to generate an excitement in me, and form in itself doesn't generate any excitement to me. For instance, I don't feel that the way to make the most free music is through music that has no limitations, like if you don't establish a tempo and you don't establish a key.

"I feel like a lot of the time the music that can be the freest is the music that has a lot of limitations put upon it. All kinds of music - from sonatas to acid house to drum and bass - have real strict parameters, and for some reason that encourages originality rather than stifles it. So for me, working in a pop group like the Chili Peppers, working basically with the pop song format, I did everything I could to try to infiltrate that with musical ideas that were exciting to me, you know?

"But that's lost its interest for me at this point. It's been a couple years now that I just don't have any interest in writing those kinds of songs. I feel like I did some interesting things within those parameters, but I have more interest in exploring different things."

Just to clarify, when you infiltrate that pop song format, as you put it, does that create any meaning—say, by having the music hit the audience differently?

"No, no, no. There are certain chord progressions I like that modulate in a certain way, or there are beats I like where certain drums fall in certain hits, but it's not as if they have any value on their own. The beat itself could be played really badly, that modulation could be terrible sounding - it's all about the person who's doing it. My knowledge of these things comes from the fact that I'm a person who likes to understand things, and because I'm obsessive, you know? [laughs] But my knowledge of those things doesn't have any musical value; my music is what it is because I'm who I am and I've lived life the way I've lived it. My sense of melody is my sense of melody."

"Even when I realized those things when I was 21, it's not as if I was thinking about them while I was playing. But I came up with drastically different types of musical ideas because of them.

"I mean, it's not luck that I make up a good guitar part, because I've got enough combinations of symbols and musical ideas swimming around in my head to where parts can be generated by referring to those things. And those coordinates where a word meets a musical moment, and the word meets the note, and those two things meet the rhythm that the word falls on, that's where the real meaning comes from."

You've covered a lot of songs, but is there one that's especially significant for you?

"My dad had Fragile on the shelf when I was a kid, so I was listening to Yes when I was like seven years old, so I heard Steve Howe and I liked him. And yeah, I love his playing on the first Lou Reed solo album. But for some reason, the chord progression that Ride Into The Sun is based on is very meaningful to me. There's something about the tonality of that song that I identify with a great deal.

"I have no idea why, but there are certain basic chord progressions that have been used thousands of times, and it's completely your interpretation of them that counts—it never sounds like the same song, you know? I feel like at various times in my life, especially when I haven't been making music, I see clearly that it's my job as a musician to explore the possibilities inherent in certain chord progressions or harmonic climates, and that's a really limited way to be thinking, which is probably why I've thought that way more when I wasn't making music than when I was." [laughs]

Not to categorize yourself, but if there are these two main schools of guitar players as we've been talking about them - the virtuoso approach and the post-punk approach, to use reductive terms - do you think of yourself as fitting into one more than the other?

"I definitely don't have any interest in aligning myself with a certain type of guitar player. But it is something I think about, and basically, I think of myself as somebody who put the same amount of time into guitar playing as a guy like Steve Vai would, but I used that time completely differently, in order to have a good grasp of a wide variety of musical colors, many of which I perceived through the study of people who played with very little technique but whose brains were nimble, whose brains in terms of creativity were exactly where you'd want to be."

"I studied those players and I applied them, so that while I was capable of doing something more based in the basic tradition - you know, I had that finger strength where I can play like a 'guitar hero' or something - but instead of using my ability that way, I tried to do something that was more based in the approaches of people who had less technique.

"And I tried to make mine a cohesive style, because like I say, a lot of these people just sort of stumbled on what they did without knowing what they were doing, and they had no control over it, which is what I like about it, but then I was able to come upon that and say, 'Well, what if I crossed Bernard Sumner's approach with Jimmy Page's?' You know? 'What if Jimmy Page tried to play like Bernard Sumner?' [laughs] 'How could I play in a rhythmic style but with no blues?'

"So yeah, I think that I'm kind of a learned guitar player who didn't have any interest in learning along the same lines as a lot of other people do. I was more interested in studying people like Fugazi and Bow Wow Wow."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

“The most musical, unique and dynamic distortion effects I’ve ever used”: Linkin Park reveal the secret weapon behind their From Zero guitar tone – and it was designed by former Poison guitarist Blues Saraceno’s dad

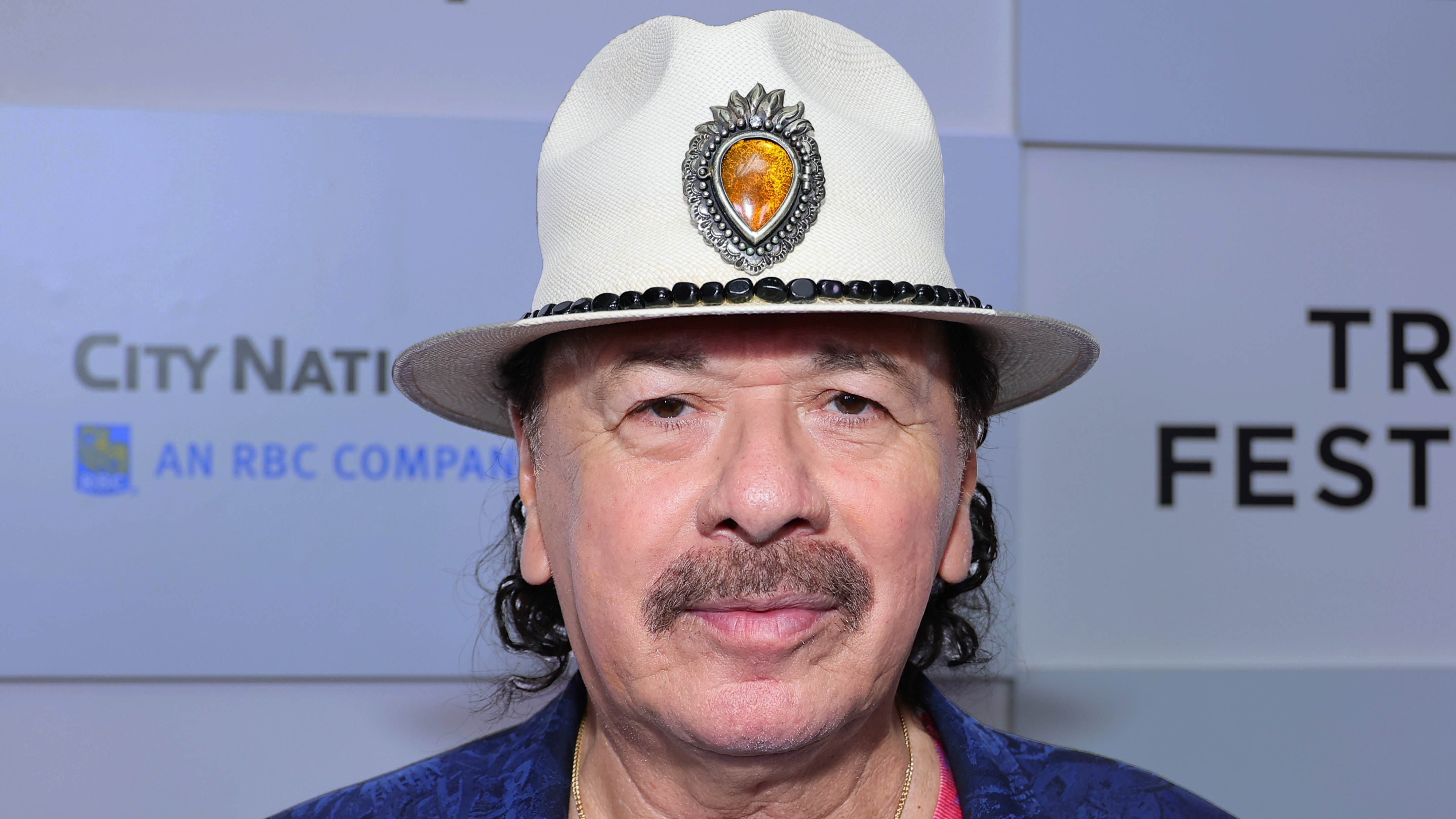

Carlos Santana collapses and then cancels second show “out of an abundance of caution”