Billy Gibbons discusses the 10-disc ZZ Top box set

In the early fall of 1970, three Houston-based, boogie-and-blues-loving musicians, guitarist-singer Billy Gibbons, bassist-singer Dusty Hill and drummer Frank Beard, walked into Robin Hood Studios in the neighboring city of Tyler to see if their "little ol' band from Texas" had what it took to make an honest-to-goodness record album.

"We were three guys, we had three chords, and the future was wide open," says Gibbons. "We called the record 'ZZ Top's First Album' because we wanted everyone to know that there would be more. We weren't certain if we'd get another chance in the studio, but we had high hopes."

On 10 June, 43 years after the release of ZZ Top's First Album, Warner Bros. will issue the 10-disc box set ZZ Top: The Complete Studio Albums (1970-1990), which traces the band's development from a raw and feisty blues club act to a groundbreaking, mainstream-rock, hit-making powerhouse.

“It’s as close as I’ve gotten to instant time travel," Gibbons says of the box set. "Taking two decades of expression and compressing them into one ready, at-your-fingertips experience is pretty remarkable."

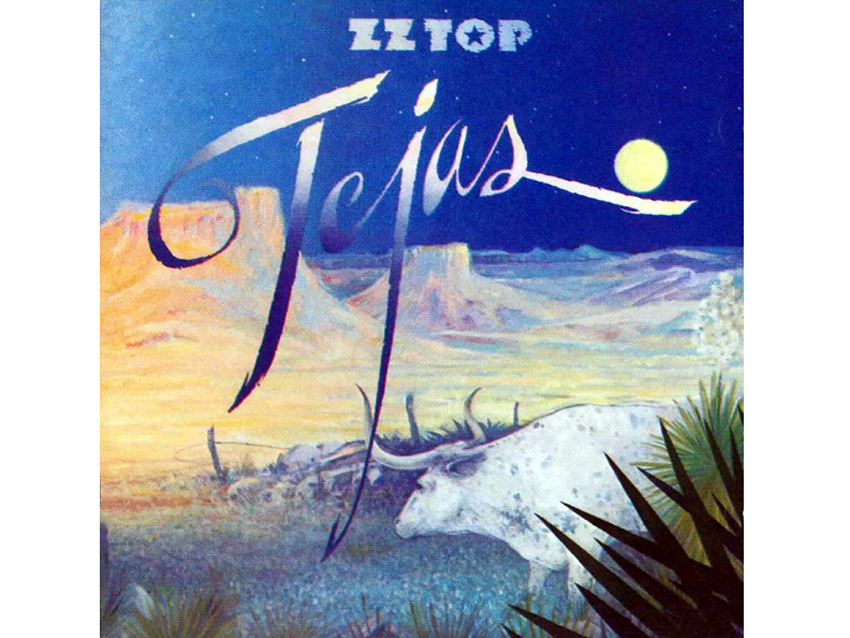

For Gibbons, one of the high cards of the package is that each album's artwork has been faithfully reproduced, including the gatefold sleeve designs used for 1973's Tres Hombres and 1976's Tejas, along with the original mixes. "Getting the unchanged experience of each release with the original mixes is such a cool deal," says Gibbons. "This is the way the albums were intended to be heard."

All 10 albums in the set were produced by Bill Ham, who, until 2006, also functioned as ZZ Top's manager and main image-maker. Gibbons says that the importance of Ham cannot be overstated. "I have to hand it to a guy who was willing to take on three rowdy and reckless teenagers and try to navigate the musical waters with them," he notes. "The task of maintaining forward motion was certainly a challenge. Bill had a masterful sense of vision, and he brought us to the point of delivering everything that was available.”

On the following pages, Gibbons reflects on the recording of all 10 records contained in ZZ Top: The Complete Studio Albums (1970-1990).

ZZ Top's First Album (1971)

“Well, we were sure hoping that there would be a second album. The art director who had stepped into ZZ Top’s world was a gentleman named Bill Narum, an extremely talented guy who had a handiness with the paintbrush and an awareness of the big picture, especially when it came to the importance of music in people’s lives.

“Mr. Narum saw the importance of titling ZZ Top’s first album, and he said, ‘Make it known that you’ve provided the world with an offering of what you guys do, and it’s just the first one.’ And we said, ‘Sure. That sounds fine with us.’ And so it became ZZ Top's First Album.

“We had been together for about six months and were knocking around the bar scene, playing all the usual funky joints. We took the studio on as an extension of the stage show. The basics were all of us playing together in one room, but we didn’t want to turn our backs on contemporary recording techniques. To give our sound as much presence and support as possible, we became a little more than a three piece with the advantages of overdubbing. It was the natural kind of support – some rhythm guitar parts, a little bit of texture. That was about it.”

Rio Grande Mud (1972)

“The underlying comfort factor was that we were recording in Texas. There was a tremendous amount of shared understanding that we had with the engineer, Robin ‘Hood’ Brian. He owned and operated the studio. Being a musician himself, he had a lot of empathy for anybody who wandered into his place. He knew how to make everyone feel at home.

“Robin did a lot to make sure we didn’t experience the dreaded ‘red light fever.’ When you’re a bunch of guys in a band playing clubs and bars, a studio can be a cold, antiseptic and intimidating place. We were still getting used to the dichotomy of the two.

“It was the first record that brought us into step with the writing experience. We started documenting events as they happened to us on the road; all of these elements went into the songwriting notebook. As we went along, we were keeping track of skeleton ideas as they popped up. The craft was certainly developing.”

Tres Hombres (1973)

“It was interesting: The third go-round was again recorded in Texas, but we accepted an invitation from a gentleman named Waltaire Baldwin – he spelled his first name differently – to appear at a famous event in Memphis called the Overton Park Blues Festival. Following that performance, we met a guy named ‘Memphis’ Robert Johnson, who told us that Led Zeppelin had just finished mixing an album in town – maybe we should do the same?

“So that’s what we did. We took our tapes from Texas and brought them to Ardent Recording, turned them over, and the end result became Tres Hombres, which yielded our first Top 10 with Le Grange.

“We had never played that song live. It was kind of a haphazard, last-minute thought that came together in all of three minutes. We were waiting for the engineer to complete his house cleaning chores, and we were jamming out. At one point, we looked through the glass and the guy was waving his arms, signaling us to continue on. The song just fell into place.

“We could tell that we had something special. The record became quite the turning point for us. The success was handwriting on the wall, because from that point we became honorary citizens of Memphis.”

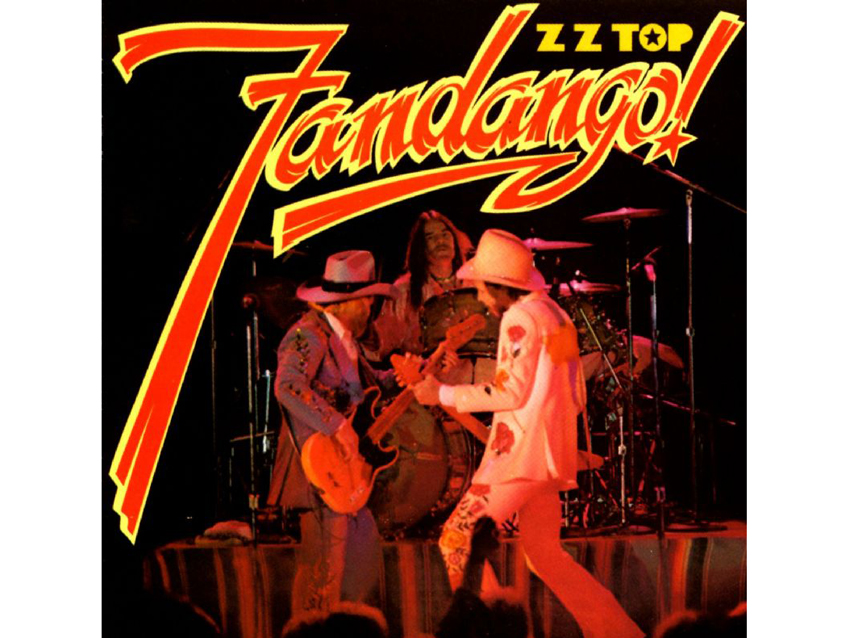

Fandango! (1975)

“The live capture wound up being in the can first. We had enough live material to make up one side of the disc, so we decided to go with the unusual move of making the album half live, half studio. It turned out to be a winning combination for us.

“One of the songs that we were playing at shows, another one of those ‘catch-it-in-three-minute’ tunes, was Tush. We had gone down to Alabama, and it started to take shape with the riff. As for the lyrics, well, it’s not exactly Bob Dylan. [Laughs] That one we recorded in the studio.

“Tush felt good from a musician standpoint. But you know, you can never tell what’s going to be a hit or not. We were enjoying the recording experience, figuring out how to grab a moment and making it repeatable.”

Tejas (1976)

“It’s fair to say that this is a transitional record, although I’m not really sure what we were transitioning from and what we were becoming. [Laughs] It may be representative of how rapidly things were changing in the studio.

“The equipment was becoming more modernized, and the way that music was being recorded was different – things were moving faster. It was still pre-digital, but there was better gear that was more readily available. We made use of it all.

“This period was the wrinkle that kind of suggested what was to come, and change would become a necessary part of the ZZ Top fabric.”

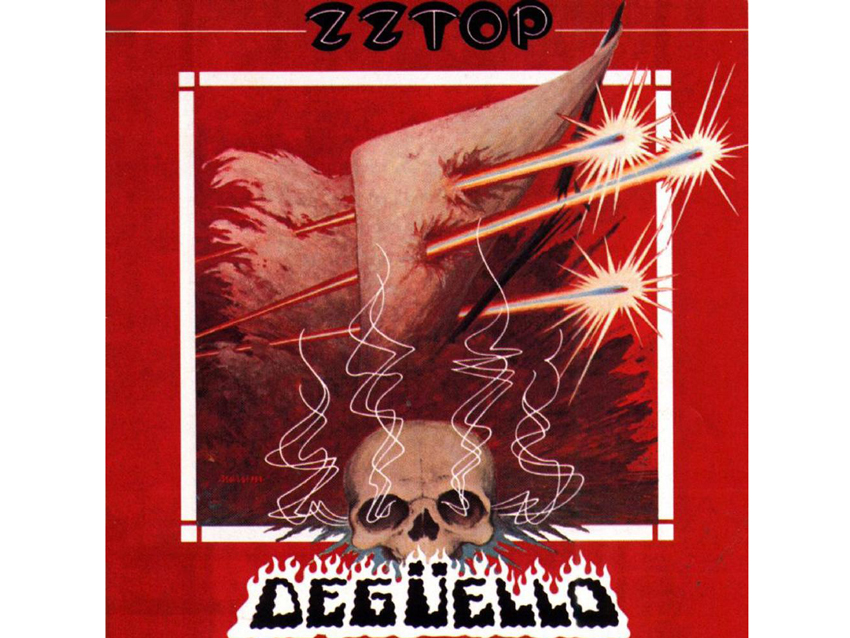

Degüello (1979)

“By this time, Memphis had made its mark with us in a really positive way. I don’t think that anyone can go there and not be affected by all of the great music, especially stuff from the Stax/Volt era.

“Before we left Memphis, the song I Thank You came on the car radio. Isaac Hayes played this badass clavinet part that made the Sam & Dave version so distinctive. I was in the studio, talking to the engineer, and I remarked about how magical the sound of the clavinet was on that song, and he said, ‘Well, lo and behold, that very same clavinet is right out there in the other room.’ I said, ‘Well, that’s it. We’re going to have to incorporate it in our version.’

“ZZ Top, in the studio, sometimes became a five and six-piece band, by way of whatever we were adding to the sound. One of the key pieces here was the use of that clavinet. We put it on I Thank You, Cheap Sunglasses – it started showing up on a lot of tracks.

“Sometimes change is hard to take for some people, but we knew how far we could push things for our fans. Also, we knew that we had to go out and do the songs live, so we avoided any elements that would have made that impossible.”

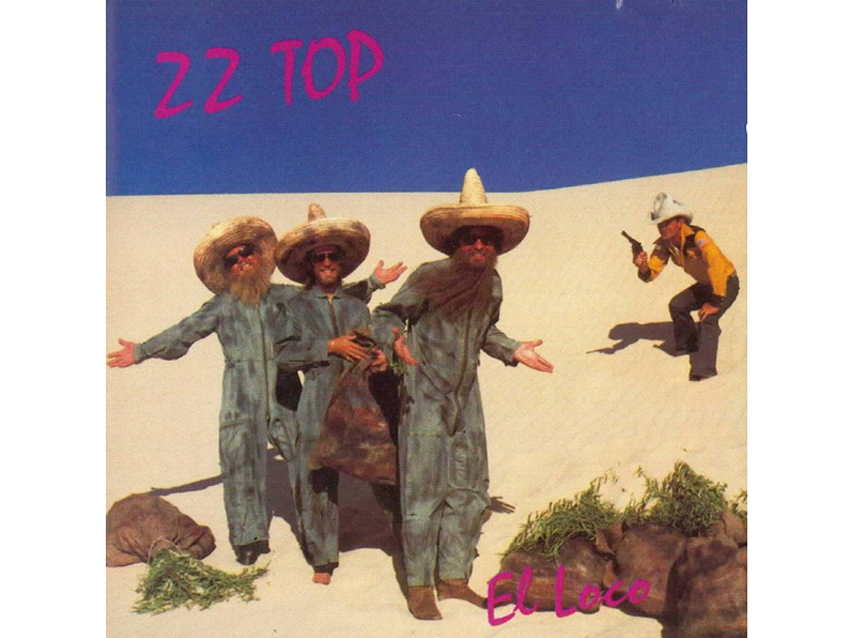

El Loco (1981)

“This was a really interesting turning point. We had befriended somebody who would become an influential associate, a guy named Linden Hudson. He was a gifted songwriter and had production skills that were leading the pack at times. He brought some elements to the forefront that helped reshape what ZZ Top were doing, starting in the studio and eventually to the live stage.

“Linden had no fear and was eager to experiment in ways that would frighten most bands. But we followed suit, and the synthesizers started to show up on record. Manufacturers were looking for ways to stimulate sales, and these instruments started appearing on the market.

“One of our favorite tracks was Groovy Little Hippie Pad. Right at the very opening, there it is – the heavy sound of a synthesizer. For us, there was no turning back.”

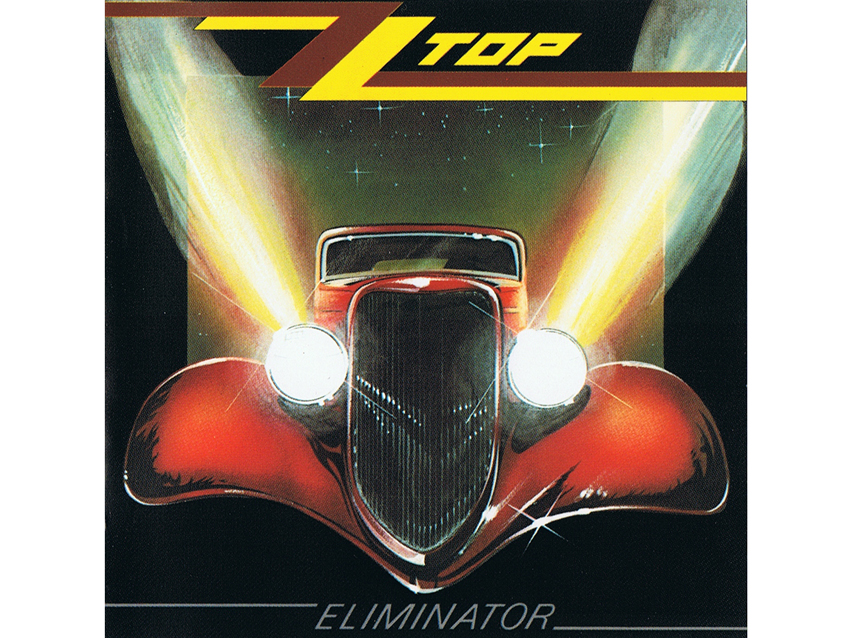

Eliminator (1983)

“The wheels were turning, the scenery was changing, and we were having a field day playing around with these crazy machines that were making wicked sounds. The funny thing was, we had no training at all; these instruments were popping up, and we just took to them.

“That’s really the best way you can discover new sounds anyway. The first thing we did was throw away the instruction manuals, and then we started twisting knobs until we said, ‘That’s what ZZ Top should sound like.’

“Eliminator also marked the point when we paid serious attention to timing and tempos. This became a benchmark that we aspired to. Once the groove was laid down, we learned how to stand on it. That’s one of the elements that makes Eliminator stand out in a classic sense; all of those tracks were timed and tuned very tight.

“Legs and Sharp Dressed Man started with their titles – they were concepts. Gimme All Your Lovin’, which was really the first single that made it off the record, started with the music. It went through a bunch of different titles and themes; over the course of three months, we had five or six versions going on before we figured it all out.

“The heaviness of the synthesizers created a nice platform that allowed the guitar to stand on its own. I think it’s because synths could play an octave below a bass guitar; there was a nice full bed of sound that contrasted with any of my guitar parts.

“Bands like Depeche Mode were leading the synthesizer charge at this time. What’s interesting is, Joe Hardy and I received an invitation from them recently to remix one of their new songs, Soothe My Soul. Dave Gahan told me they were looking for a little ‘Texas mud’ to go with the electronica. Funny how things go around in circles sometimes.”

Afterburner (1985)

“The runaway success of Eliminator really put us on the burner to meet or beat that which had gone before. Having the experience of experimentation led us quite easily to the next wave of sensibilities. There was some great stuff that inspired the follow-ups.

“Planet Of Women, Rough Boy, Sleeping Bag – there’s some really cool tunes here. It was all in good fun and in keeping with the spirit that Eliminator had established and broke open for us.

“The synths were very much in the analogue domain. Robert Moog was making available a lot of the technology that had broken through under his guidance. Suddenly, you could walk into a music store, throw down some cash and be ready to rock. The one model that we used quite a bit was the Moog Source; it’s the device that provided the super-low sound. Man, that was great.

“Even though we taught ourselves to use the synths, there was a pretty hard learning curve required to work them. They weren’t quite as user-friendly as everything we have today. Many late-night hours we spent twisting knobs and going through trial-and-error – you twisted one knob and it affected everything else. Once we landed on something, we left well enough alone.”

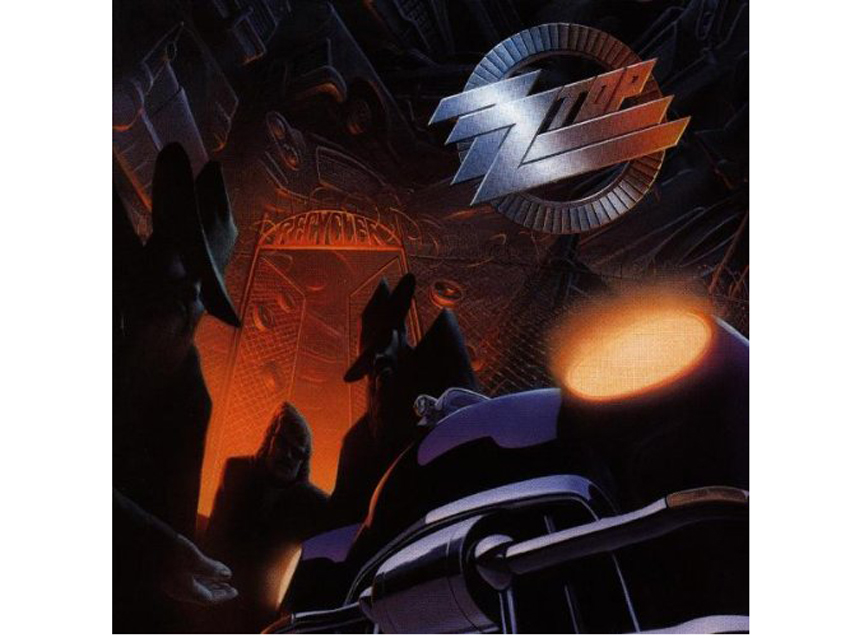

Recycler (1990)

“The forward motion stimulated by Eliminator carried over onto Afterburner and wound up with Recycler, and as had been the case, it rested on the backbone of timing and tuning.

“This was probably the last hardcore synth-styled release before we began drifting back to the roots. By this time, we were actually looking forward to the studio experience. Whatever was state of the art, it was there on the floor at Ardent Recording. They were always first to embrace it and make it available to their clients.

“My Head’s In Mississippi is representative of where we were headed, back to the boogie and groove. That song’s in the current lineup, too – we played it last night, and we’ll play it tonight.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues

"Reggae is more freeform than the blues. But more important, reggae is for everyone": Bob Marley and the Wailers' Catch a Fire, track-by-track

“Part of a beautiful American tradition”: A music theory expert explains the country roots of Beyoncé’s Texas Hold ‘Em, and why it also owes a debt to the blues