Bill Corgan on recording The Smashing Pumpkins' Monuments To An Elegy

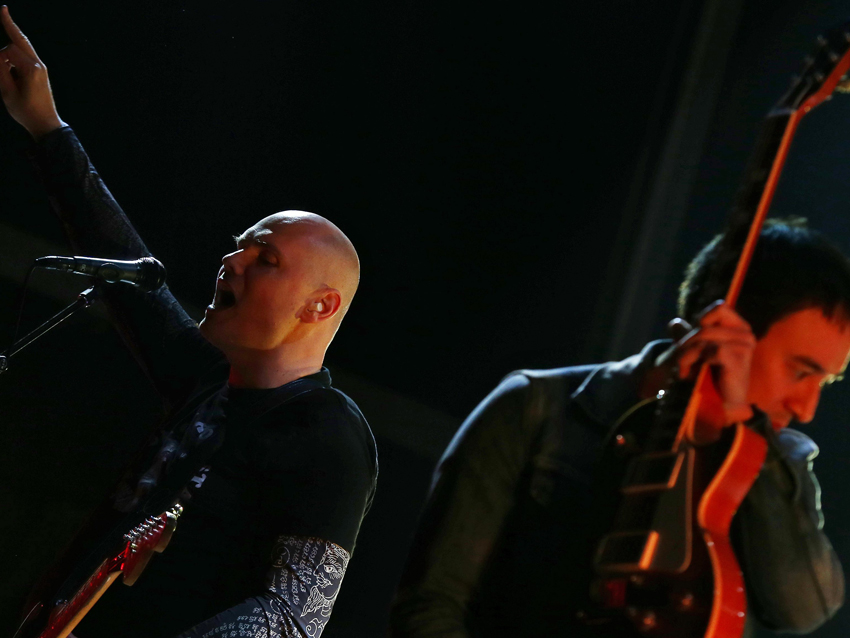

Even as the guitars rise to a level of overwhelming tectonic force on The Smashing Pumpkins' upcoming 10th studio album, Monuments To An Elegy, Billy Corgan's aching tenor hovers angelically above the fray, seemingly indicating that the mercurial bandleader is enjoying a period of relative contentment. Throughout the nine-song disc, he sounds beatific, blissed-out even, a stark contrast to the first or even second impressions many have of the Chicago rocker as the angst-fueled Explainer In Chief for his generation.

“I’m in a better place in my life," Corgan admits with a gentle laugh. "I think a lot of people have impressions of me that aren’t real, so I feel that when I talk about being happy or more content in my life that I’m talking about a mythical opposite of that guy who supposedly exists or doesn’t exist.”

He pauses thoughtfully, then adds, "I’ve literally had people walk up to me on the street and say, ‘You’re the rat in a cage guy,' or ‘You’re the Smashing Pumpkins guy.’ It’s how they identify me, and that’s fine – it means I did one thing right. But it doesn’t define me. Like anybody’s life, there’s good times and bad times. This is a better time than others, and I think that does translate to the music.”

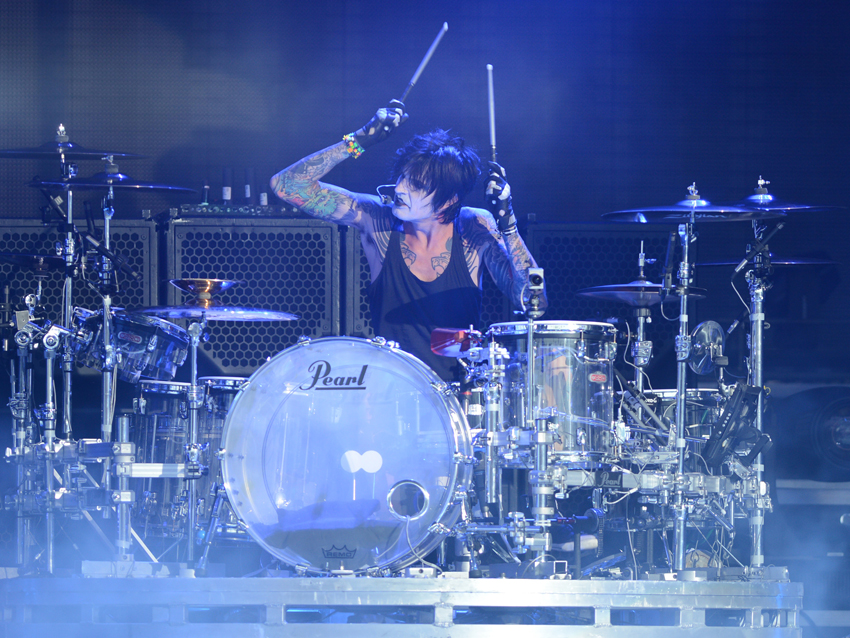

Monuments To An Elegy, due out December 9th, is the second full-album installment immersed in the ongoing 44-song project, Teargarden by Kaleidyscope – Corgan says that the next record, Day For Night, planned for next year, will complete the set – and it sees The Smashing Pumpkins' lineup, which for the past few years included drummer Mike Byrne and bassist Nicole Fiorentino, down to the core duo of Corgan and guitarist Jeff Schroeder. To much ballyhoo earlier this year, Motley Crue drummer Tommy Lee guested on the set, and the success of this gambit can be measured in how fully integrated he sounds on each track – he neither apes past styles nor imposes his own sensibilities on the music.

"Tommy completely committed to the process," Corgan enthuses. "He played differently than he would in certain circumstances, and the way he normally played in certain circumstances was perfect. It made us sound fresh again in that maybe the busier style of Pumpkins drumming does. He's really remarkable."

In the following interview with MusicRadar, Corgan opens up about the recording process for the new album, working with Tommy Lee, the evolution of the band's sound and whom he might be performing with on stage next year. (You can pre-order Monuments To An Elegy at iTunes. Information on limited-edition vinyl, along with special CP + LP versions, is available at The Smashing Pumpkins website.)

The album is nine songs – that's a nice, tight statement.

“That was the plan going in. I just feel that it’s hard to achieve a high level of quality past a certain number of tracks. Combine that with the fact that the audience doesn’t seem to be listening to complete albums the way they used to, so it made sense to go back to a smaller scale. I mean, I remember having records as a kid that were eight songs long. Boston’s first album was eight songs. So maybe it’s going back to a mentality that the album is something that isn’t going to take up too much of your time, especially if it’s a rock ‘n’ roll record and not something conceptual.”

Do you miss that, though? The whole album experience that we used to have…

“I do. It’s hard to explain without going into a lengthy diatribe, but the Pumpkins isn’t in this current guise what it was necessarily designed to do. There’s a level of disappointment to that, because it was never meant to be a pop-rock group. [Laughs] It was meant to be a rock group with populist tendencies – and ever moving forward musically. But I don’t know anybody who could have foretold the changes in both the music business and the musical culture. Nowadays you have albums coming out that literally sound like they were made 20 years ago, and the audience is totally cool with it.”

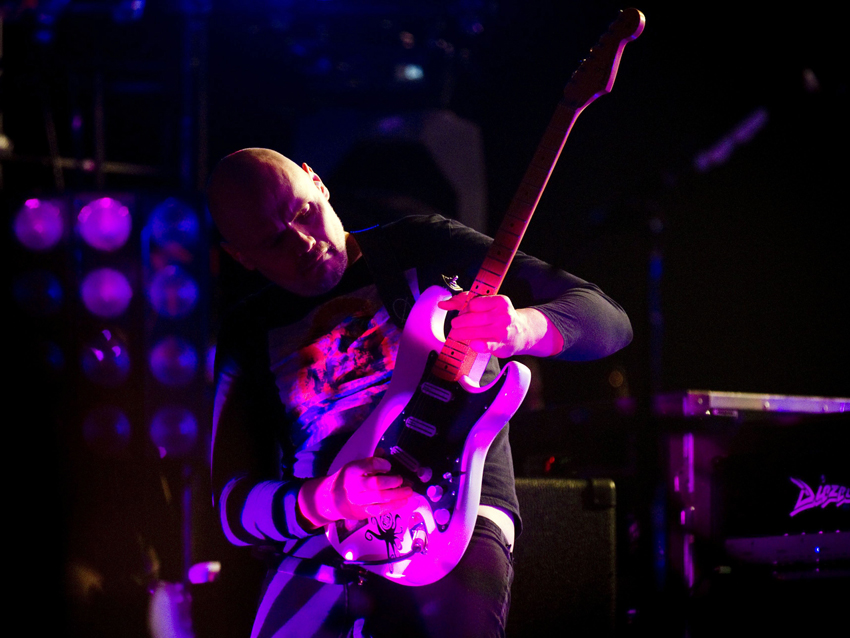

Unless I missed something, there’s no guitar solos on the record.

“Well, there’s a subtle solo at the end of the very last song [Anti-Hero]. That’s about it. We didn’t plan to have no solos; there was no edict, like, ‘Thy shall have no solos.’ It just didn’t feel like it was part of this record. The last record had lots of guitar work in that vein. We went out and played the album in full, and although it was enjoyable, it wasn’t a visceral experience for either the band or the audience. It’s not as if people are clamoring for our solos.

“There was a time in Pumpkins music where I think the solo was a part of the epic arrangement mentality, but that’s come and gone, too. I do know that we’re trying to redefine the way we play guitar, and that might in a sense mean taking a step backwards to simplicity is a way for us to take a step forward – going forward.”

On guitarist Jeff Schroeder

How would you say Jeff is complementing what you do on the guitar? I’ll be honest: I can’t tell who’s playing which guitar parts.

“Well, sure, and there’s a reason for that: Our styles are kind of melded in a way so that you can’t tell who’s playing what. I have a hard time myself sometimes; I’ll hear a track and I’ll say to Jeff, ‘Is that me or that you?’ [Laughs]

“I’d say that Jeff’s biggest contribution, not that it screams out at anyone, is that he’s playing the other side of the rhythm picture. That combination has a fresh feel to me, as opposed to my normal thing where I would do all the rhythm overdubbing to get that super-tight sound, which people identify as the Pumpkins sound. Jeff is filling the other side, and he’s brought new life to that approach.

“As far as the melodic stuff that drops in over the top, we just take turns and work through it together. Maybe it’s not as individualized as it could be, but on top of that there’s a lot of overt guitar work and subliminal guitar work going on. There’s a really cool part, for example, that Jeff plays on Being Beige that sort of sits in the rhythm picture – you wouldn’t even know it was there if you didn’t go looking for it. I wouldn’t say it’s a lead per se; it’s a one- or two-note thing. I almost popped it out because we needed more space in the track, but the whole thing fell apart without it. I think Jeff has really matured into somebody who wants to be supportive of tracks and has no ego whether you can quote unquote hear what he’s playing.”

Sometimes when a name drummer guests on somebody else’s album, you can tell who it is, but Tommy Lee sounds fully integrated into the music.

“He does. When we talked and he agreed to do this, I said, ‘Now, look, it won’t be a service to you or me if it sounds like you just showed up and played on this record. This is a different kind of music, so if we do this, we’re gonna go all in together.’ He said, ‘Absolutely.’ And he was good to his word.

“We worked really hard together. We went through every part, every bit. He would laugh sometimes and say, ‘Wow, I’m not used to working this hard.’ [Laughs] But I said, ‘Look, the greatest thing we can do here is the compliment you’re giving us, which is that you sound like you’re in the band.”

On Tommy Lee

He really does. On the first track, Tiberius, he’s hitting every accent. It’s as if he developed the song with you.

“And that’s not the easiest thing to achieve. I’ve worked with people who don’t always trust my instincts on where a particular accent should go or whatever. Tommy was really willing to follow my lead; he was totally invested in making sure that I felt great about what was happening. I have nothing but praise for him. He’s a great musician, and like all great musicians, he can play effortlessly. He can do take after take, and it’s not like a magic trick – he really is that guy.”

I imagine that he was jazzed to get a little out of his wheelhouse. I don’t see him guesting on a lot of records.

“I think this is a little outside of his comfort zone. I think that most people who call him up want him to play like Tommy Lee. I was looking for super-prog Tommy Lee – that’s a better way of putting it. There were times when I would make a reference that he wouldn’t know, and we’d have to work through it. But his commitment to the process speaks really highly of him. He’s a very famous man, a very wealthy man, and he’s got a lot of things to do, including hanging out with his beautiful fiancé. I’m very proud of the kinship that we've developed. That’s not something you can just do.”

Has there been any discussion about Tommy playing live with you next year?

“We have talked about it in sort of a ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if Tommy were here or there and could play on a couple of songs?’ type of way. That’s about the extent of it. The Crue tour is endless – you know, they’re saying goodbye, so they have lots of places to go.”

Keyboards are used quite subtly on the album. Nothing is very overt – they’re simple, graceful little lines.

“That’s a lot of hit-or-miss, throwing stuff at the wall. I’ve got cool vintage synths, so a lot of times it’s all about taking them out and experimenting. One cool thing about the synth work I’ve done over the past few years is that it’s helped me understand the architecture of synthesis. Now, just like on a guitar, I can get what I want out of a synth. Back in the day when I was working with Flood, he was into all of that modular synthesis and I was your typical button-pusher. If it wasn’t a preset and I couldn’t get what I wanted by sliding a knob, then that was the end of it.

“So now, every sound that you hear is custom tailored. It’s me going into a particular set of sounds and popping the hood to get whatever function out of them I want. I feel really comfortable in that world, whereas before I was truly a novice.”

Writing killer-riff songs

You pull off a really neat trick. The keyboard lines on Tiberius, Being Beige and Monuments are very subtle, but they're so effective. I don’t think the songs would be the same without them.

“I think so. On Tiberius, the keyboard that’s under the heavy guitars, is a pretty cool one. It’s a Synthacon. It’s fairly rare – they didn’t make that many, and then I think they went out of business. Great, cool sounds. You’ve heard it on In The Light by Zeppelin, that intro that John Paul Jones plays – ‘Doo-doo-doo-doo-doo.’

"It’s a very fussy keyboard, and in messing about with it, I realized that it makes this subtle detuning at every sort of keystroke, which makes for a cool track only that it pushes the track slightly out of tune every time I hit a note. With that, you have to do multiple takes to find the one that works the best, because it’s such a random process. You have to let your instincts almost rule over what might be the best way to do it.”

Again, talking about subtleties, I love the guitar riff in One And All, and what really makes it special is that little slur you do at the very end of it.

[Laughs] “Yeah, that one came together purely because we thought we needed some more rock songs. We pulled out a couple of guitars and were just jamming away on the couch, and all of a sudden I hit that riff out of nowhere. I was literally just jerking around, and I played that whole riff – the entire thing, with the resolve – and I went, ‘That’s it!’ Five minutes later, I was on a microphone singing the melodies. It just seemed to work.

“A comparable song from my catalog is Zero. Same thing: The riffs came easily, and then after that it fell into place. You can spend years trying to write stuff like Zero, and it just won’t happen, but one day it pops into your head.”

The beat to Run2Me is almost a disco. Was that always the idea?

“It’s a four-on-the-floor, but I don’t disagree with that – a disco beat. You have to give credit for that to Tommy. He built those drums up. He felt that the track organically – i.e., him playing the kick drum – wasn’t that exciting, so he went in and programmed the thing up. Then he did a bunch of overdubs on top of it, and that really turned the corner on the track.”

Anaise! also has a curious beat – it’s almost a military rhythm. The ‘80s-sounding synths complement it in a very cool way.

“That song originally was almost like a Gish-era Pumpkins song. No matter what we did to it, it just wouldn’t turn the corner. I even tried to get Tommy to demo an earlier version that was heavier, and he was like, ‘I’m not feeling it.’ It wasn’t until I said, ‘It’s not gonna work,’ and I tried some other stuff. Before I knew it, I was playing that bassline, something straight out of Another One Bites The Dust or whatever. That one worked – it felt cool. Sometimes the traditional ways to doing things are less effective. When you roll the dice and play something that has almost a contrast, that's when it works because that forces you to play differently and think differently.”

Recording with a full band

This record was made by you, Jeff and Tommy. Do you long for the days when you had a stable band to work with in the studio?

“I think I’ve given up on the idea of a band. It’s not even personal; I just think it’s the way I work. I’ve mostly worked as a loner through the years. Maybe it’s my place in life, but I don’t feel like doing a lot of negotiating. There were times with Mike and Nicole, who are both very skilled musicians and who have great ideas, where they wanted to do it this way but I wanted to do it that way. I didn’t think they were wrong and I was right or I was wrong and they were right. There are just those moments when somebody has to have that score to the big picture, and the only ones I’ve ever had that big picture feeling with are the ones I’ve had the most success with.

“If I had that feeling with Flood, Butch Vig, Alan Moulder and Jimmy Chamberlin, I have it now with Jeff, and by extension with Tommy Lee. That seems to be the place where the great stuff happens. I don’t feel like arguing with someone about ‘big picture’ or ‘not big picture,’ because I can’t honestly look them in the eye and say they’re wrong. They’re not wrong – it’s just a perspective.

“But when I’ve been able to meet people on the big picture stage of ideas... It’s like when I would play a riff that had a big picture to it and Jimmy Chamberlin then played a drum beat that had a big picture to it. Or like now when I play something like Tiberius and Tommy Lee plays the dream beat in my mind. It’s not that he’s playing the beat that’s in my mind – he’s playing the dream beat in my mind, which is even better. So that’s where things go the best. Everything beneath that gets into a lot of ‘who’s right, who’s wrong, who’s gotta make the call,’ and I’ve just gotten to a point where I don’t wanna do much of that anymore.”

Are you getting to the point where you might be like a modern-day Brian Wilson? You’ll make records on your own, with Jeff or with other people, but it’ll still called The Smashing Pumpkins?

“I don’t know. I don’t care what it’s called anymore. Here’s the simplest way to explain that: We’re about to go play some shows to support the new record. If I were on that stage playing the exact same setlist with a different name – Billy Corgan And The Spaceships – the expectations on me are no different. However, the business is different, the way I’m treated is different and the way I’m received is different simply because of the name over my head. So at some point, I was like, ‘OK, let’s be as overt as humanly possible. You’ll deal with your end of the expectations, out in the open, and I will, too.’

“But it’s very frustrating to be a solo artist, for example, and have the same expectations that exist with The Smashing Pumpkins without the power that exists behind The Smashing Pumpkins’ name. It is, at this point, innate, and I don’t pretend that it’s not innate. I just gave interviews in Europe where I said, ‘The band at this point is more of a concept.’ It’s like a binding force or something, like it binds me to a certain set of ideals, and I’m cool with that. I don’t always like it, but I know what it is, and I think the audience knows what it is, and we just go on from there.”

On co-producer Howard Willing

Aside from possible gigs with Tommy Lee, have you given thought to who’s going to be on stage with you next year?

“I have. It’s going to be a great thing that I wish I could tell you about, but I can’t. It’ll definitely be an all-star band. It’ll cause a stir, which is good. We start rehearsals any day now. For some reason, we can’t announce it yet. It’s not in my hands.”

Of your co-producer, Howard Willing, you’d said that he’s “in the real world,” and you’re not. What does that mean vis a vis the day-to-day process of making a record?

“Howard used to record a lot of singer-songwriters, and in allegiance to the artists, he became frustrated seeing a lot of them not get their due because they weren’t able to produce records that could be competitive in the marketplace. At some point, he became unsentimental about what you have to do with your production and song arrangements to be competitive. So he has to play the bad cop and say, ‘Yeah, that’s great and it’s really cool, but to somebody who’s 22 and listens to this type of music, they’re probably not gonna pay much attention to it.’ He plays traffic cop.

“Howard’s my friend, and he’s worked with me on two very difficult albums, Adore and Machina. He saw me really struggle to find a particular voice on those albums, and he also watched me when those albums weren’t particularly well received – in their time. I don’t know if that’s changed with time. Howard has a very personal interest in me being relevant and contemporary. He understands the frustration of not being able to translate ideas that he believes in across the aisle, so to speak.

“I do need someone like Howard. I need someone to remind me what’s going on in the world, because honestly, I don’t listen. I don’t pay attention. Sometimes we’ll be fussing over something, and we’ll say to Howard, ‘Play us something you think is great that illustrates the point you’re trying to make.’ And he’ll play us some contemporary track and we’ll kind of laugh – ‘Are you kidding? That’s what you think we should be doing?’ Six months ago it was four-on-the-floor kick drums; now it’s half-time epic drums.

“But when he demonstrates those things to us, it’s not like we go, ‘Yeah, we’ve got to do that.’ In my eyes, we’re finding a way so that Pumpkins music can relate to or supersede that feeling in much the same way as when we heard the rock bands of our time, and in the early ‘90s we set out to destroy them by being bigger, faster, bolder.”

The Smashing Pumpkins sound

Regarding the band's sound, it's there on the new album, and it's always been present on the band's recordings, but you don't sound married to it. You don't try to ape or recreate, say, Siamese Dream.

“The old Pumpkins sound is dated. People keep calling for it, but in many cases what they want is over 20 years old. The fact that it’s remotely relevant, mostly because of contemporaries of mine who continue to make the same kind of music – and have success with it – doesn’t mean it’s not stale. I wouldn’t try to pass it off as fresh.

“It’s a tricky thing, but I don’t think the Pumpkins’ style circa ’92 to ’93 is contemporary. It’s just not. Some bands transcend the need to change because what they do is perfect. AC/DC doesn’t need to change because what they do is perfect. I’ve never thought that what I did was perfect. If I did, I’d keep doing it. A lot of people cite Siamese Dream as being a sort of perfect statement, but if I weren’t willing to move off of that, you’d never have an album like Mellon Collie, and so on.

“You pick your road. Some people make one type of cabinet, and that’s what they’ll do till the day they die. I was never like that. To quote Pete Townshend, I’m a seeker. If I’m wrong, I’m wrong. I don’t sweat it as people think I do. It’s just music, as my father would say.”

Is there a ballpark release date for Day For Night? Where are you at it?

“That’s a tough one. To be honest, I’m struggling. It’s really hard to say. I think we learned a lot with Monuments, and we tried to apply those things we’ve learned, but we just haven’t succeeded. We could go backwards and pick up where we left off with Monuments and make a pretty good record, or we could keep doing what we’re doing, which is to find this spot on the other side of this rainbow. There are signs and moments where I go, ‘It’s there,’ but I haven’t been able to put it all together as a writer. It’s a struggle, but it’s the right struggle.”

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.