Bill Wyman on stage with his band, Bill Wyman's Rhythm Kings, in Monte Carlo, Monaco. © Pool/People Avenue/Corbis

"Most musicians play clubs and dream of being in stadiums," says Bill Wyman. "I was the other way around. Everybody thought I must've been crazy to leave The Rolling Stones, but it was something that was on my mind for a while. It was something I had to do."

When Wyman quit The Greatest Rock And Roll Band In The World in 1992, ending a 30-year association that produced some of the most vital recordings of the post-Baby Boom Era, he wasted little time in assembling a new band, Bill Wyman's Rhythm Kings, one which would allow the bassist to perform the music he loved in more intimate venues.

"For a long time in the Stones, I missed having contact with the audience," he says. "Standing there with your bass in a football field, you become isolated. With the Rhythm Kings, the band is totally engaged with the people who've come to see us. I quite like it."

Being an ex-Rolling Stone has its perks, of course, as evidenced by some of the A-list names that have popped up on Rhythm Kings recordings over the years: Eric Clapton, George Harrison, Mark Knopfler, Nicky Hopkins, Peter Frampton and fellow former Stone Mick Taylor - all have played with Wyman and company on their four studio albums.

And those discs now make up the five-CD boxset titled Collectors' Edition Box Set, due out 25 October, which neatly packages Wyman's stunning examination of 20th Century roots music, along with originals that suit the same period to a T.

MusicRadar sat down with Bill Wyman to discuss the Rhythm Kings and a few of the iconic musicians who have played with the band. In addition, we talked about bass playing and gear, as well as that other group he used to mess around with.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

So how does one become a Rhythm King?

[laughs] "Joining up in the beginning is probably the way to do it. Other than that, you have to hang out and wait for someone to get injured. It's like a football team: If some gets injured, or is called off to do something more lucrative, because we're a big band that plays small venues, you've got your shot.

"The great thing is, we're basically the same band now as when we started in 1994. I've got Georgie Fame on organ; Albert Lee and Terry Taylor on guitars; Graham Broad on drums; the same horn players, Frank Mead and Nick Payn; and my girl singer, Beverley Skeete. Occasionally, people come and go, so I guess you have a chance…if you're good enough." [laughs]

When you went back and listened to the albums for the boxset, did you like what you heard?

"I did, yes. Sometimes, when you do something like this, you hear a track and you wish you could change a part here and there. But I think these records are quite good. I especially like the double CD, Double Bill. There was a lot of material on that one, and so we had to make it a double record. The name fits - 'Double Bill.'" [laughs]

You're doing another tour soon. Don't you ever think of retiring?

"Retiring? What's that? [laughs] You mean sit around and do nothing? I don't think I'd know how."

Yeah. But you were in The Rolling Stones. You guys would wait three, four years to make an album or tour.

"That's true, but I would do other things. That's why I got involved in doing my own music and art projects and things like that. Otherwise, I'd go crazy.

"As for The Rhythm Kings, we usually do two tours a year, one in the spring and one in the autumn. Every time we go out, we usually try to get a guest artist. Over the years, we've had Eddie Floyd, who was fantastic. Then we had Gary U.S. Bonds, and he was great. I loved all the stuff he used to sing back in the '60s. The guy can still do the business, too. He gets it going.

"So for this next tour, we're going to have Mary Wilson from the Supremes singing with us. She's amazing, you know. I've admired her since I first met her in 1964. She's done some gigs with us before, so it won't be like breaking in somebody new. This should be a lot of fun."

Are you planning a new Rhythm Kings studio album?

"Actually, we've already started it. We've got about eight tracks done. Part of the process with it is finding some gems from the past that people have forgotten about. I don't want to do the same old songs that everybody's done. And then there's originals that I might have written with Terry Taylor or by myself that will sit nicely with the other tunes. We tend to do two-thirds covers and one-third originals."

When picking covers, how do you go about it? Do you have a lot of these songs committed to memory, or do you go through your record collection?

"Well, I'm always listening to music. I listen to iTunes and I tend to pick things out. Occasionally, something will leap out at me and I'll go, 'Wow! Bloody hell, we could do that.' [laughs] It's like that, really. I'll go, 'Yeah, Beverley can sing that, I can play that…' That's it, pretty much."

Let's talk about some of the guitarists you've played with over the years in the Rhythm Kings. What was working with Eric Clapton like?

"Eric's fine. I've asked him to do me a favor and play on a couple of tracks, because I've done a lot of stuff with him in the past, Howlin' Wolf tracks and things like that. I've also done some things with him for charities, which was always nice. I asked him to do some overdubs, so he said, 'Send me the tapes,' and that was that. His playing is great."

You've also had Mark Knopfler contribute to some tracks.

"Yeah. Mark actually came to the studio. It's always good when the person is there and you can have some interaction. I've known Mark for some years now. He's a very sweet man. We go out to dinner from time to time and all that. Our wives are very good friends, as well.

"That's the thing about some of us: We're a pretty close-knit community in London. You've got Eric Clapton around the corner, and you've got Mark Knopfler up the road. Then various members of the Stones are nearby. Charlie's local, I seem him quite a lot. Everybody's around. George Harrison was different, because he lived way up in Henley."

How did you come to work with George?

"Well, I hadn't seen him in a number of years. I wrote to him, and then I called him up and said that I had a track, this song called Love Letters, that I wanted him to do a solo on. He said, 'Bill, you've got Albert Lee and Martin Taylor in your band, two of the best guitarists in the world. Why do you want me?' [laughs]

"That's how George was, very humble. 'But I only play one note,' he said. And I told him, 'Well, that's the note I want.' He did a wonderful job. He died a year later. We did Taxman on the next record in his honor."

Since forming the Rhythm Kings, you've written some songs with Mick Taylor. When the two of you were in The Rolling Stones, did you write together?

"The Stones were a closed shop. No entry. That was the sign on the door: 'Do not enter.' So you didn't even try. This was quite disappointing for both of us, because if you had an idea, it got used on a track and became 'Jagger-Richards.' And that was always the case. I learned to live with it and did things outside of the Stones. Mick had to leave - he couldn't deal with the frustration.

"Also, towards the end of his time with the Stones, Mick got heavy into drugs. If you ask me, drugs destroyed his creativity. It's a shame. When I was doing the Rhythm Kings in the early 2000s, I asked him to do some stuff, to help him out, really. He had no money, no guitars… I had to loan him a guitar and an amp. It was all quite sad. We used him for three days, but all we could keep was a bit of a slide solo.

"Since then, he's improved a bit. I've seen him abroad, and he's been fine. He's come on stage with us a few times and was good. Recently, he joined the Charlie Watts Band with me and Ronnie Wood when we did the tribute to Ian Stewart. He played really nice. Still, I think it's a bit of a struggle for him."

For yourself and the band, do you have any dos and don'ts when it comes to recording?

"Yeah, get on with it! [laughs] Seriously Nobody believes me, but everything we do is either take one, two or three. We never go past a third take. Whether it's a Fats Waller tune or something by Creedence Clearwater Revival, in order to capture the essence of the song, it's got to be done fast. Play it well and be done with it."

Regarding your basses, what are you using these days?

"I play a Steinberger - the guitar body, not the thin body. I tried out one of those little Steinbergers in the early '80s, the one that looks like a machine gun. I didn't like the feel. The full-size ones are good. I like those very much.

"You know what's funny? I made a bass in 1961, before I joined the Stones, and it was a fretless bass. It was the first fretless bass ever made. I didn't know that at the time, and I didn't know that until 10 years ago. It predated fretless basses by about five or six years.

"I've just had a bass made that's a clone of the '61. It's called the Bill Wyman Signature Bass. It's short-scale, lightweight, it's everything I need. I used it during some summer festivals, and it was fantastic. I think it'll be a great bass for young people to learn on because it's small - it's not this big bass that's heavy and hard to manage."

What kind of amps do you use?

"Oh, I don't get too technical. As long as it's an Ampeg, I'm all right. It's got to be an Ampeg with an 18-inch speaker. That's all I care about."

Back in the day, you used Dan Armstrong basses.

"Yeah, they were all right. I liked most of the basses I played. As long as the bass wasn't too big, I was OK. The Fender Mustangs were good, but they were just a bit too big for me. You know, that's why I held the bass the way I did, because I had to get my hands around the neck."

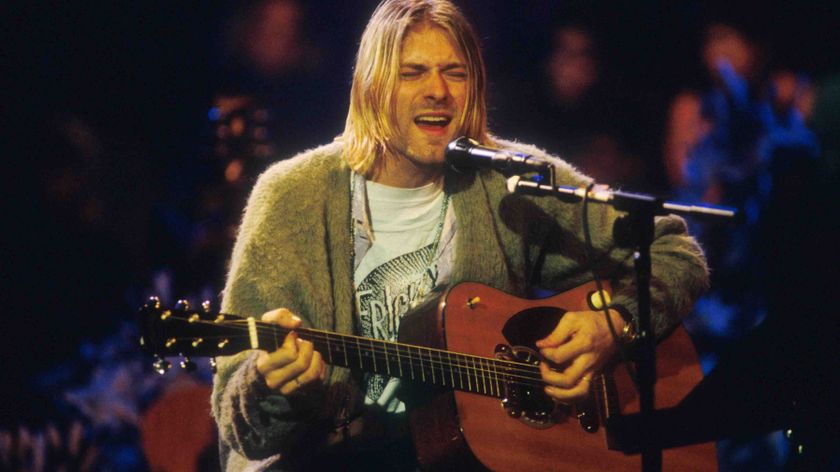

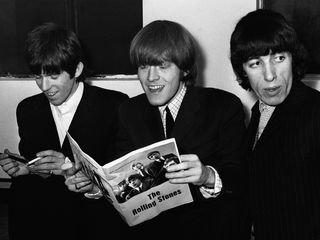

Wyman with a couple of 'weavers' - Keith Richards and Brian Jones - in 1965. © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

What about the Vox Teardrop basses? Were those OK for you?

"I didn't like those at all. [laughs] You know, they just made those basses and they put my name on them. They didn't ask me how I'd like the thing sized, how it should look, what it should be made out of - they just put it out and called it 'The Bill Wyman Bass.' I think they gave me an organ as an advance payment. I got the organ and never heard another thing about the basses." [laughs]

A couple more Rolling Stones questions…

"Uh-oh!" [laughs]

Oh, c'mon. Nothing terrible. The 'guitar-weaving' that Keith would do, whether it was with Brian Jones, Mick Taylor or Ronnie Wood - how would you fit into it all?

"Well, the only weaving I ever heard was Brian and Keith in the early days, when they would do some Jimmy Reed stuff. The two of them did play linking lines back then, and it was quite amazing. They could be quite brilliant, those two.

"As for myself…I didn't think about it, really. I just laid back, the same as Charlie did. I'm not a busy player, I never way. I just gave Keith and Brian the room to do what they needed to do. Playing clever lines and being all technical didn't impress me much - never did and never will."

In most great bands, it's usually about following the drummer. Is that what you did with Charlie?

"Yeah, but the only problem with that was, he was following Keith! [laughs] So if Keith fucked up, Charlie fucked up, and then there I was, following the two of 'em and trying to sort myself out. [laughs] But that's why we had that interesting wobble to our sound. Charlie was always behind the beat because he was listening to Keith, and I was ahead of Charlie because I was anticipating Keith. Somehow, it all worked out."

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.