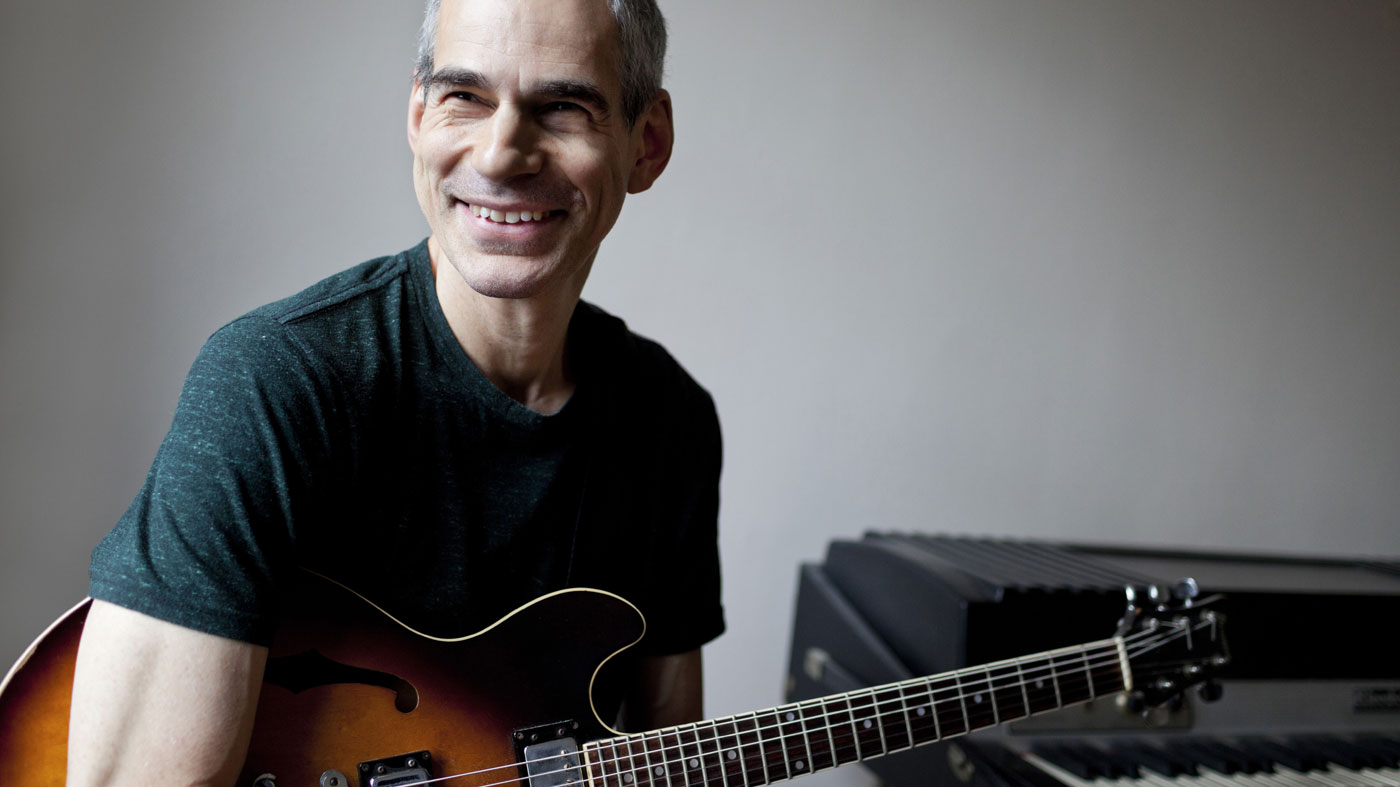

Ben Monder talks playing on David Bowie's Blackstar and the New York jazz world

The NYC guitarist reflects on a whirlwind year

Introduction

It’s a Cinderella story - you’re a jazz guitarist eking out a living in New York and then, one day, you’re invited to play on the new David Bowie album…

January 2016 saw the release of David Bowie’s final album, Blackstar. Typically anti-commercial in approach but as compelling as ever, Blackstar seems to hark back to what was arguably one of Bowie’s most creative periods, when the infamous ‘Berlin Trilogy’ - Low, Heroes and Lodger - turned rock music on its head and provided a formidable aftershock to what many considered to be the premature demise of the Ziggy era some years before.

For this new recording, Bowie had issued the edict that there were to be no rock musicians on the album. On Blackstar, he wanted to gather together the cream of the New York modern-jazz scene in order to summon a suitable musical landscape in which his new material could thrive. Enter Ben Monder, an NYC-based jazz guitarist with a track record for creating his own startlingly original music, very much on his own terms.

“I started playing when I was 11 and I’m 53. So there you go, do the math!” he laughs, in order to indicate that he’s no starry-eyed youngster who has been suddenly plunged into the twilight zone of musical adventuring. Quite the reverse, in fact. We thought that a little background information might be necessary before we ask the big question, however.

So what made you pick the guitar up in the first place?

In high school, a friend of mine played me [John Coltrane’s] A Love Supreme and that kind of blew my head wide open

“My first influences were, I guess, my parents’ Beatles records and various other types of pop music that was in the house or on the radio. I definitely started out as a rock player and I got interested in jazz, really, when I started taking lessons.

“The guitar teacher at the local music school was a jazz teacher, so kind of by default, I started learning jazz and that was at the age of 14, 15. But I’ve always had an interest and a love for playing rock, so that’s been a constant, even though I kind of immersed myself in learning jazz in my late teens, early 20s.”

Which jazz players have had the greatest influence on your playing?

“The first jazz record I ever bought was one of the first Joe Pass Virtuoso records and that was pretty mind-boggling for a neophyte like me - and I think there was a Barney Kessel record that I really liked… That was my entry into the jazz world. It was very straightahead type of music. And then, at some point in high school, a friend of mine played me [John Coltrane’s] A Love Supreme and that kind of blew my head wide open. But the early influences were definitely more the traditional stream of jazz playing.”

What form did your jazz studies take - did you work through transcriptions?

“I did some Pat Martino, some Wes solos, I soon got into John Scofield’s playing pretty heavily and I transcribed some of that. You know, I should probably say that my biggest overall jazz guitar influence would have to be Jim Hall, who I haven’t mentioned yet. Just because he’s such a complete musician on the guitar. He’s more than a guitarist, he’s the master of economy and treats the guitar like a little orchestra.”

So you were attracted to fusion players as well as the mainstream beboppers?

To my detriment, I was kind of a passive type of person and so I wasn’t really hustling to get jazz work

“Yeah, I love the Mahavishnu records, for sure. I guess, growing up, McLaughlin wasn’t as big an influence as someone like Allan Holdsworth or John Scofield, as much as I love his playing. Then I shifted over into being more interested in saxophone players. At the time, their harmonic sense was a little bit more interesting, more colourful, so I started transcribing a lot of sax solos, trying to figure out what they were doing. But guitar, at this point, has come a long way. There are people doing all kinds of amazing things. Back then, it was kind of the sax players’ domain - more harmonic explorations in a linear sense.”

When did you begin to play in the clubs?

“I didn’t really start playing in clubs until maybe the age of 20, 21. The drinking age was younger when I was that age. It used to be 18 and then they raised it to 21. I ended up going to college but I didn’t finish, I dropped out at the age of 22. I was then going part-time and I was playing a lot of weddings and a lot of R&B gigs.

“Most of my gigs were with this funk band I had, so not too many professional jazz engagements until a few years later. To my detriment, I was kind of a passive type of person and so I wasn’t really hustling to get jazz work, I was just kind of playing with friends and trying to learn the language and studying. But the R&B stuff kind of fell into my lap, so I just went with that - and I was working enough. Then, eventually, I just dropped out of school.”

You’ve lived in New York all your life. What’s your impression of the current jazz scene there?

“It was challenging then to get work - I mean, playing creative music - and I’m thinking it’s probably 20 times more challenging now because there are so many more people vying for the same spots. But it was, and is, really, a fertile place and a place to just learn a lot and I was able to see some really amazing live music. Also, at that age, I caught the loft jazz scene and it was just great; you could just pay a five-dollar cover, bring your own drinks or whatever and just stay for three sets of some of the most energetic, striking jazz that there was, so that was great.”

Don't Miss

David Bowie's guitarists on working with a rock 'n' roll icon

A new world

When did you begin writing and playing your own material?

“Let’s see, I’m kind of a late bloomer as far as that stuff goes. I had some kind of blockage against finishing a batch of original music. It just took me forever and so I didn’t end up making the first record under my name till I was about 32.

I listened to David Bowie’s records when I was growing up and my roots are in rock and pop, so it felt pretty natural to fit into that

“I had tried before that; all my friends made records before me and I thought, ‘It’s time for me to make a record,’ and I made a couple of demo tapes. I think my first demo tape, I sent 70 cassettes to various labels. I wrote an eloquent-sounding cover letter and just tried to talk myself up, which was very uncomfortable for me. I got about 35 rejections and 35 silences, so it was kind of discouraging.

“At the moment, I’m a little bit in between projects. I do trio gigs under my name, but I don’t have regular personnel at this point. We get together and I’ve been playing a lot of covers going back to my pop roots, but improvising over them and some standards and some of the easier originals that I’ve written. The closest thing to an original project is the duo I have with the singer Theo Bleckmann. We do a lot of my tunes. I’ve also been doing more and more solo gigs and so that’s something I’m probably going to pursue more than I used to.”

How did you come to be invited to play on the new David Bowie album?

“The Bowie thing started with his project with [jazz composer and band leader] Maria Schneider, who I’d played with for about 20 years. As you probably know, they collaborated on a single [Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime) from Nothing Has Changed] and so he met [saxophonist] Donny McCaslin through that band and then, I guess, Maria took him to see Donny play. He decided to hire Donny’s band and I used to play with them, when Donny had guitar instead of keyboards, so he thought it might not be the worst idea to hire me for the Bowie project, which I was very grateful for!”

Did you experience a kind of culture shock, commuting from the jazz world to the higher reaches of rock?

“Well, you know, not so much, because like I said, I started out listening to that stuff. I mean, I certainly listened to David Bowie’s records when I was growing up and my roots are in rock and pop, so it felt pretty natural to fit into that. I didn’t think I’d have to adapt or change my aesthetic too much - and I had an excuse to bring my S-type guitar, which I play maybe once every couple of years. It’s got a Fernandes body and an ESP neck. It’s had some old pre-CBS Fender pickups put on it and so it sounds really good, I really like it.”

Players who have worked with Bowie in the past says that he tended not to direct the musicians too strongly - some, in fact, have said that he could be vague on occasion…

“I wouldn’t use the term ‘vague’. I had a lot of freedom to create parts and to add what I thought was appropriate. So yeah, he was not dictatorial at all; he definitely had a clear vision of what he wanted. When something wasn’t working he would say so, but he was also really open to our contributions, and so it was a really nice supportive and creative environment.”

How long did the sessions run?

“The rest of the band did a total of three weeks - separate weeks, spaced apart - and I joined them for the final week. I guess we were all there for four days, then I did the last day by myself, just doing overdubs and basically just trying to come up with parts, trying to invent stuff over some of the tunes that had been laid down already.”

You’ve already mentioned your S-type hybrid guitar. What other gear did you use for the sessions?

I would leave the studio every day in a state of elation. I certainly had no idea I would be participating in his final project

“I went stereo through two amps that I own: a ’65 Deluxe amp and a ’68 Princeton. They work pretty well in stereo, they complement each other. Then I have an Ernie Ball volume pedal, my reverb is a modified [Lexicon] LXP-1, I have an MXR Carbon Copy Analog Delay, a couple of nice Walrus Audio pedals - I have a Deep Six compressor and a distortion called the Mayflower, they make some great stuff. I also have a modified RAT, so two different distortions. Sometimes I use them both together and sometimes separately. I also have a [Fulltone] DejáVibe and a [Strymon] Blue Sky reverb pedal. It has this cool shimmer effect, so I occasionally use that, but try not to overdo it.”

Was the whole experience like some kind of weird dream for you?

“I wouldn’t say that. Of course, in a way, it was kind of a dream come true! It was such a great opportunity to do it and I really loved the material. I thought the songs were all really strong. I know they recorded 12 of them and seven are on the record and I think the songs are great. But, you know, you’re in the studio and you just go in with the mindset of a professional just trying to do a good job and so I wasn’t too weirded out by the situation.”

How does it feel to have played a part in Bowie’s final album?

“The experience of working on Blackstar was a great one. David was such a joy to work with, a really great guy, and of course I loved the songs he was bringing in. I would leave the studio every day in a state of elation. I certainly had no idea I would be participating in his final project. There was a darkness to some of the material but I never read anything too dire into it. The news of his passing has come as a total shock to me. He was unquestionably one of the most brilliant creative minds of our time, whose music has meant a great deal to me since I was a kid.”

For information on Ben Monder’s latest solo studio album, Hydra, head to the official Ben Monder website.

Don't Miss

David Bowie's guitarists on working with a rock 'n' roll icon