Anatomy of an acoustic

ACOUSTIC WEEK: Ever wondered what’s inside your acoustic guitar? We open one up to help explain what’s going on in there and how it affects your sound.

Helping to unravel the DNA of an acoustic guitar for us is veteran guitar builder Patrick James Eggle. Pat and his team make beautiful guitars at his Oswestry workshop.

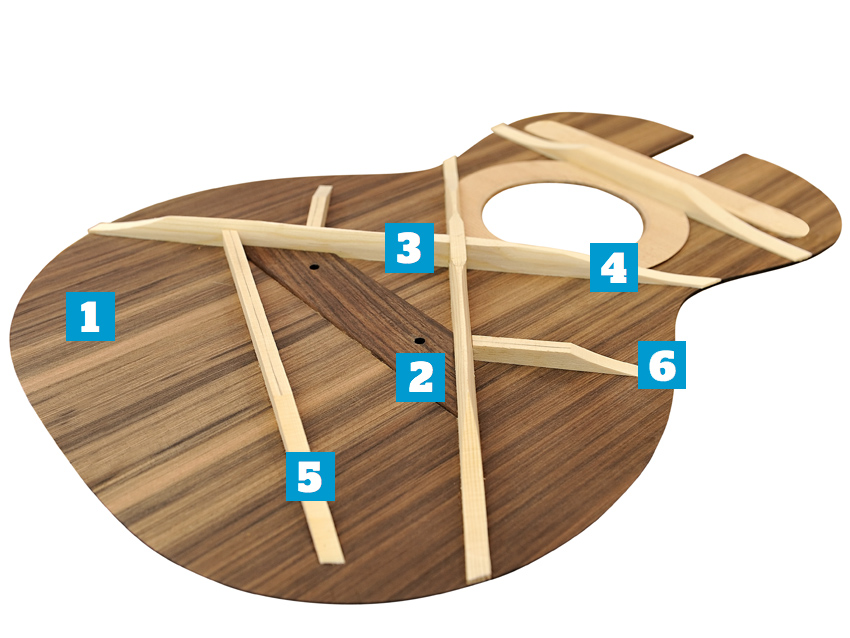

The top

1. Soundboard

“In very general terms the top is the ‘speaker cone’ of the guitar,” offers Eggle. “It’s the thing that responds to the vibration of the strings and beats in and out, which starts the air moving.

“When we’re selecting a top, one of the first things that we do is check the stiffness. I’m after tops that are stiff across the grain. With a weaker piece of wood, you’d have to leave it thicker to give it sufficient strength. But that extra thickness would also make it less responsive, meaning it would take longer to react to vibration from the strings.

“By contrast, a stiffer, stronger piece of wood can be made into a thinner top so the response is more immediate and dynamic. What you’re looking for is a ’board that’s perfectly quarter- sawn; the growth rings will lie at right angles to the top of the guitar.

"A slab-sawn ’board is often a lot more pretty to look at, with more figure exhibited – but it’s also less stable and won’t have as much strength. Some pieces of wood are just naturally better, acoustically, than others. Generally, if you get a bright, glassy, resonant sound just by tapping it, that will translate into the instrument.”

2. Bridgeplate

Underneath the top will be glued a (usually) maple bridgeplate that is there to strengthen and protect the softwood top where it’s drilled to accept the string- anchoring pins. Guitar makers have used different materials over the years; size and material drastically affect the tone of the guitar (Martin’s 1970s rosewood bridgeplates are often cited as the ‘bad’ example.

The company returned to using maple and continues to use it to this day). This bridge itself is glued to the top, ideally to a section of bare, unfinished soundboard. Its size and material affects tone significantly, in the same way it does for fingerboards.

3. Forward shifting

You’ll see this term used to describe where the whole X-brace is shifted forwards so the centre of the X is roughly one inch from the edge of the soundhole (instead of two, which is broadly speaking ‘standard X-bracing’).

In theory, forward shifting enables the top to vibrate more because the bridge isn’t sitting directly above the very strongest part of the X: so it’s louder and bassier. That’s how Martin used to do it on the fabled pre-War models. It’s very reductionist to talk tonal attributes as a result of measurements in isolation, but this at least explains the term.

4. X-bracing

There are many approaches to top bracing. The most popular for flat top steel-string guitars is the classic X-brace introduced by Martin in the mid-1800s (classical guitars are usually fan-braced). “The top’s nowhere near strong enough on its own,” explains Eggle, “so it needs bracing. A set of 0.012 strings on a standard scale acoustic generates around 180lbs of pull. That’s the weight of an average bloke – imagine that being supported by a bit of spruce 2.5mm thick for 40 years! That’s a big ask, really.

“I keep coming back to the traditional X-bracing – it works for us. Each brace is tapered: that’s a strong shape. We could leave them square, but that would retain a lot more mass [and deaden the sound] without adding strength; each brace gets its strength from its height, not from its width.”

5. Tone bars

In addition to the main X-brace, most steel-string flat-tops will have two tone bars behind the bridge, to support the back of the top. The position of these and the extent to which they are shaped or scalloped has a big influence on the vibration of the top, and therefore the sound of the guitar, just as it does with the other remaining braces.

6. Scalloping

An extension of the tapering that Eggle describes above, many quality steel string flat- tops have carefully scalloped bracing. That’s where meat is removed along the length of the braces – it’s enough to ensure the top is free to vibrate fully, not so much to compromise structural integrity.

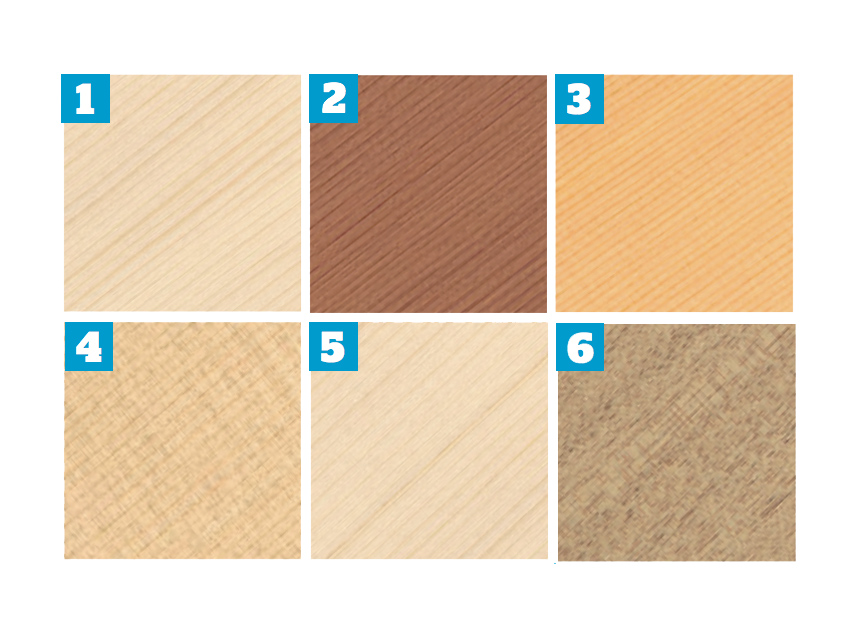

Woods

1. ADIRONDACK SPRUCE

(Picea rubens)

The King Of Top Woods (also called ‘red’ spruce) hails from eastern North

America and Canada. It can be driven hard, but remains dynamic and toneful right across the spectrum. It’s also the most expensive option.

2. WESTERN RED CEDAR

(Thuja plicata)

Darker in colour and generally ‘softer’ sounding than spruce. It usually

offers more dynamic range to lighter fingerstyles. The trade off is reduced dynamics and compression when played hard.

3. SITKA SPRUCE

(Picea sitchensis)

Found in North America and Canada, this is the most common wood

for tops. A good mix of strength, clarity and dynamic range over a variety of styles and looks.

4. ENGELMANN SPRUCE

(Picea engelmanni)

Native to western America and Canada, this is usually an upgrade

from Sitka, albeit ‘different’ rather than ‘better’. It’s lighter and less stiff; it can give a subtly richer sound than Sitka.

5. GERMAN SPRUCE

(Picea abies)

Not to be confused with Engelmann, but it exhibits similar tonal qualities. Also

called European spruce (as are other European spruces), and is popular for classical guitars.

6. MAHOGANY

A group of species, the best of which is/ was from Central and South America. It’s a

hard wood (unlike the others), and is more dense, which often means a more direct sound.

Back and sides

1. Back & sides

“The back and sides really do influence tone,” says Eggle. “You want the sides to be very stiff and solid because you don’t want energy from the strings to dissipate into them. You want that energy to be directed into the top and then for the top to be banging up and down and getting air moving. The back of the guitar will then reflect sound toward the listener.

“Our guitars are built with a 15ft radius on the back and the tops have a 30ft radius. So the top’s got an arch to it but it’s very nearly flat – while the back arch is more pronounced. I’m actually making my backs thicker and thicker these days. If you stiffen up the back you seem to get more projection and more volume out of the front end of the instrument, which seems to be what people want.”

2. Bracing

The back of the guitar also needs to be braced for strength. Unlike the top, it tends be in a ladder pattern in most steel-string flat-top acoustics; it’s less complex than the top bracing because tonal effect is not as critical and there’s no soundhole to consider.

The strip down the middle covers up the join in a two- piece back. Some guitar designs – such as Taylor’s 100 series – have no back bracing at all as the laminate back is arched (much more radically than Eggle mentions above) to provide the necessary strength.

Inside the sides

1. Neck block

The neck block is a critical component of the guitar body into which the neck is either screwed, glued or both. Its design will differ depending on the type of neck joint

(see over the page).

2. Lining

This joins the top and back to the sides. In days gone by, it would be a long strip of wood with slits (kerfs, hence the term ‘kerfing’) cut along the whole length. These days, the kerfs are usually CNC machined to provide a light and flexible surface to which back, top and sides are glued. Some guitars have solid lining.

3. End block

Joining and strengthening at the rear, the end block also houses the rear strap button/endpin. Put the guitar down too heavily on the endpin and these blocks can split, which is a nightmare to repair – one reason that Martin, for example, ships its guitars without the endpin installed.

4. Side struts

Not all acoustic guitars have these; they’re there simply to add strength to the sides, helping to prevent splits.

Woods

1. BRAZILIAN ROSEWOOD

(Dalbergia nigra)

The Big One. These days, Brazilian or ‘Rio’ rosewood is protected to the

point where it’s almost unusable and untransportable. Martin stopped using it for ‘normal’ backs and sides in 1967, but it is still available as custom order from certain manufacturers. Expect to pay massive money for this rich, warm-sounding and often breathtakingly beautiful piece of arboreal history.

2. OVANGKOL

(Guibourtia ehie)

This is a rosewood variant/alternative from Africa, usually lighter in colour and

less expensive. More and more companies are starting to use it for guitar making. An all-rounder.

3. MAPLE

(Acer genus)

A group of species including eastern and western American varieties. It can look

fantastic thanks to heavy figuring, and tends to exhibit a bright, punchy character; less warmth in the mids than rosewood or mahogany, but with good, solid bass. A strummer’s dream, if we’re allowed (yet another) generalisation.

4. KOAS & WALNUTS

There are plenty of other hard woods used for backs and sides, often as much

for aesthetic as tonal reasons. Koa (Acacia koa) is, loosely, tonally somewhere between mahogany and maple; walnuts (Juglans genus) between mahogany and rosewood.

5. ‘NEW’ WOODS

With increasing environmental concerns and legislation over the

use of tropical hardwoods, a number of manufacturers are looking for more sustainable timbers. Mariner Guitars is an example of a modern brand doing just that with its use of the paulownia species.

6. LAMINATES & HPL

Despite generally negative press, laminates can share some of the tonal

stamps of their solid counterparts. Quality, two- and three-piece approaches are a credible option. High-pressure laminates (HPL) are modern, sustainable and environmentally aware materials gaining popularity, if not ultimate critical acclaim for sound and looks.

7. OTHER ROSEWOODS

(Dalbergia genus)

The species within the Dalbergia genus are many and varied: Indian tends to be

dark in colour; Madagascar often lighter; Cocobolo can be very highly figured. Whatever, they tend to be ‘warmer’ sounding than mahoganies due to more tonal colour in the lower mids and mid-range. Trebles have more sizzle and presence than mahogany in general.

8. MAHOGANIES

Due to the way Martin and Gibson have used/priced it since the 1930s, mahogany

is often considered the ‘lesser’ tonewood to rosewood. Not so: it’s often ‘cleaner’ and more direct than rosewood with fewer mid-range overtones. The best stuff has deep, powerful bass and direct, strong trebles with superb, piano-like string separation when partnered with spruce. Genuine mahoganies are from the Swietenia genus, but the term mahogany is also (confusingly) applied to lots of related woods from Asia, Africa and the Americas.

9. SAPELE

(Entandrophragma cylindricum)

An African species seen more and more in recent years, it’s similar to mahogany

in many respects, albeit in more plentiful supply and more sustainable. Not as traditionally pretty to look at, and a little more zingy sounding to our ears.

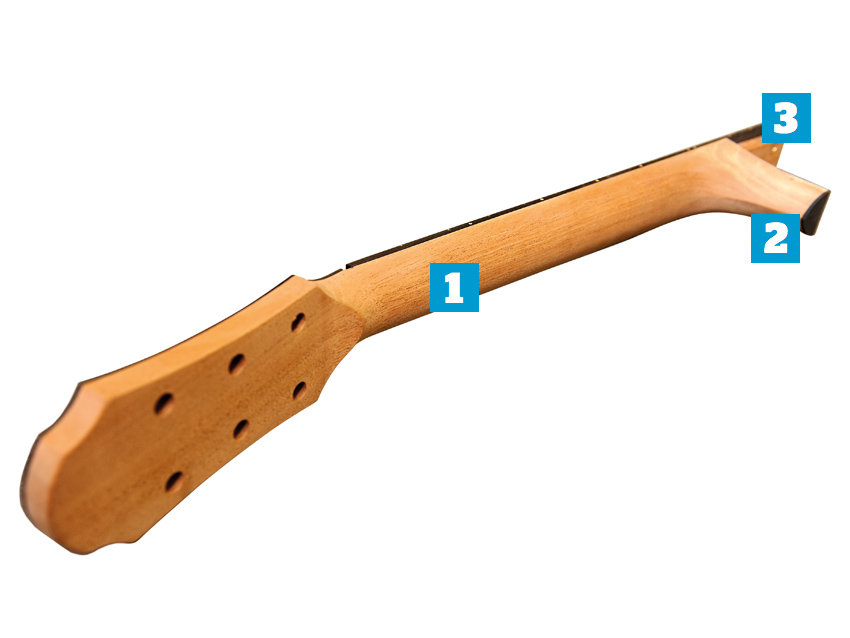

The neck, part one

1. Neck

Mahogany is the most common neck wood and, increasingly, Spanish cedar (Cedrela odorata; very similar to mahogany and not to be confused with western red cedar on p63). Maple and maple laminates are also used.

“You want the neck to be stiff,” says Eggle. “Once you hit the string, that kinetic energy has to go somewhere. If you’ve got a very thin, whippy neck then a lot of the energy can be dispersed through it, which isn’t doing anything for the sound. You want all the energy to go into the bridge, to get the top working.”

2.Heel

As with the headstock, on very high-end/vintage-style guitars, this will be hewn from the same piece of wood as the neck. Most manufacturers, though, will build the lower heel out of separate pieces. Heels vary in shape and size, but it’s here, slightly towards the lower bout, that is the most structurally sound position for your second strap button.

3. Neck joint

Dovetail, glued: the traditional method for attaching neck to body. A shaped ‘tail’ is cut into the neck block, into which a corresponding ‘pin’ on the end of the neck heel is fitted.

“Purists will say it’s got to be a dovetail,” comments Eggle, “because that’s the best join. If it’s good then yes... but most of the time they’re not. I’ve done a lot of neck resets on vintage guitars, and not-so vintage ones, and what you’ll normally find when you take a dovetail neck off is a load of bits of veneer and glue – and fresh air!” Mortise and tenon, bolted: Martin, Taylor and Collings, to name just three, use their own variations of this method. Eggle explains his...

“There are two holes for M6 bolts that go into the neck,” he says. “There’s also a fretboard extension and under that is a mahogany block that has small brass inserts, which are bolted from underneath. It’s a solid joint, but you can still take the neck off in a couple of minutes, which is great if you want to do a neck reset or anything.”

The neck, part two

1. Headstock

Carving both neck and headstock from a single piece of wood is wasteful and expensive, so many makers use a separate headstock, attached with a scarf or finger joint. The same is true for the outer edges of headstocks: the ‘ears’, which are often simply stuck on.

Angling the headstock back creates down pressure as the strings go across the nut, which is beneficial to vibration and sound. You may also see a volute on the rear, a small protrusion of wood that was originally there for strength at this weak juncture. These days, it’s more likely to be purely for aesthetics. Many acoustic headstocks will have a decorative wood overlay, often to match the fingerboard and bridge.

2. Nut (slot only shown)

“The nut can be made of various materials,” explains Eggle, “synthetic ivory, plastic, bone, Corian... It must be hard so it doesn’t wear through, and it shouldn’t bind the string when you’re tuning. The nut and the saddle material on an acoustic can greatly alter the tone; bone sounds very different from brass, from Tusq, and so on.”

As for nut widths, serious fingerstyle players tend to go for a ‘wide’ nut option (more than the relatively ‘standard’ 44.5mm/1.75 inches. Pure strummers tend to prefer something a little tighter.

There are no rules, especially as the neck back shape has a big effect on feel too.

3. Fingerboard

Most acoustic ’boards are ebony or rosewood, though man-made materials such as Richlite are becoming more popular. Ebony ’boards accentuate the high- and low-end clarity of the tone (it’s a more dense wood) compared with rosewood. Ebony sounds ‘brighter’, generally.

Acoustic guitar fingerboard radii tend to be between 15 and 18 inches, much flatter than on most electric guitars.

4. Frets

Acoustic guitar frets tend to be a little thinner than those fitted to many electrics, because there’s less string bending going on.

5. Truss rod

The same as on an electric guitar, the truss rod is there to counteract the tension of the strings on the neck. The truss rod is usually adjustable from either the headstock end (underneath a truss rod cover), or through the soundhole.

Guitarist is the longest established UK guitar magazine, offering gear reviews, artist interviews, techniques lessons and loads more, in print, on tablet and on smartphones Digital: http://bit.ly/GuitaristiOS If you love guitars, you'll love Guitarist. Find us in print, on Newsstand for iPad, iPhone and other digital readers

“For those on the hunt for a great quality 12-string electro-acoustic that won’t break the bank, it's a no-brainer”: Martin X Series Remastered D-X2E Brazilian 12-String review

“Beyond its beauty, the cocobolo contributes to the guitar’s overall projection and sustain”: Cort’s stunning new Gold Series acoustic is a love letter to an exotic tone wood

“For those on the hunt for a great quality 12-string electro-acoustic that won’t break the bank, it's a no-brainer”: Martin X Series Remastered D-X2E Brazilian 12-String review

“Beyond its beauty, the cocobolo contributes to the guitar’s overall projection and sustain”: Cort’s stunning new Gold Series acoustic is a love letter to an exotic tone wood