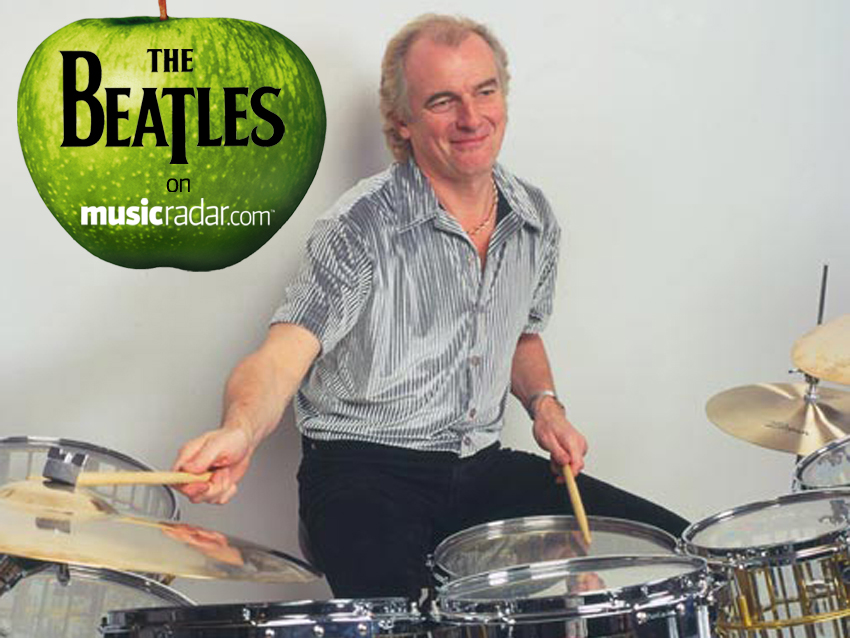

It's not every day a Beatle calls you and changes your life forever. But that's what happened to Alan White in 1969. Before he began his nearly 40-year-career as the drummer for Yes, White received a phone call from a man who said he was John Lennon. He thought it was a prank.

Only it wasn't. Lennon had just seen White play in a club and wanted him for a new group he was putting together, The Plastic Ono Band.

During the next few years, White became Lennon's go-to guy, and when Lennon introduced him to George Harrison, George was so taken by the drummer's immense skills that he used him on his triple- album breakthrough smash All Things Must Pass.

In the following interview, White recalls those heady days and talks fondly of his memories of performing with two of music's biggest icons.

So let's set the picture here, Alan. You're taking a shower, the phone rings and a guy who says he's John Lennon is on the other line.

"That's exactly right. I was sure it was somebody playing a joke, so I hung up. A minute later the phone rang again, and sure enough, it really was John Lennon. He said he'd seen me play the night before in a club - I was gigging with a local band - he liked what I did, and he wanted me to play in Toronto for this peace event. I didn't have time to think, but of course I said, 'Sure.' You don't say no to John Lennon."

Talk about a twist of fate.

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"Oh, the biggest. The next day, a limo arrived and took me to Heathrow Airport, and once there I was taken to the VIP lounge, where I met John and Eric Clapton, Yoko, Klaus Voorman. We talked about what we were going to play and we rehearsed on the plane. In mid-air we became The Plastic Ono Band."

Tell me the truth - were you freaking out just a little? Here you are, an unknown drummer about to play with rock royalty.

"Strangely enough, I took the whole thing in stride. It wasn't until years later that I went, 'Wow, what an amazing thing to have happened!'" [laughs]

"The plane ride to Toronto was something else: With a pair of drumsticks, I was playing on the seat in front of me and we ran down the numbers we were going to play, things like Blue Suede Shoes. One thing that always stuck in my mind was how John said to me, 'Now, remember, Alan, the way Carl Perkins played it, there's an extra beat after the line, 'Well there's one for the money - da-da-duh!' John was very conscious of details like that."

The gig went down extremely well, of course.

"It was wonderful. Aside from The Beatles' rooftop thing, John hadn't performed live for a few years, and I know he really enjoyed Toronto. He was elated, in fact. I think after the show he decided that he was really going to leave The Beatles. Or maybe he had thought it before, but that show gave him the confidence he needed. And I take no responsibility in that! [laughs] I'm sure The Beatles were going to break up no matter what happened in Toronto."

It's funny: You're known as a progressive-rock drummer, yet you've played on some very important records by Lennon and George Harrison. Did they ever tell you specifically what they liked about your playing?

"No. They didn't dole out compliments like that, nothing specific. That just wasn't their style. I think they were so used to Ringo, who always just knew what to do - to them, a drummer played the drums and that was that.

"The only thing that John ever said to me was, 'Alan, what you're doing is absolutely fantastic. Just keep doing what you're doing.'"

It takes a certain kind of drummer who can play the very intricate music of Yes, but yet you laid down a huge, straight-forward beat in Instant Karma! with genuine feel.

"Luckily, I never listened to any one type of music. I wasn't a jazz snob or a progressive snob - if the song was good, I liked it."

Working with Phil Spector on Instant Karma! - what was that like?

"Phil was a quiet guy. He never said too much. He and John would confer about things and I would be in the control room trying to figure out what they were saying. I tossed out some ideas for how the drum parts should go, and they ended up using them.

"The parts in the song where the drums kind of explode, the fills that I do - I came up with this idea of going off the meter, playing a fill and then going back into the main rhythm. I kind of sprang it on John and Phil and they loved it. Phil said, 'Alan, just keep doing that. It's making the whole song!' [laughs]

"It was interesting watching Phil do a bit of his Wall Of Sound technique: you didn't play one tambourine, you played 15 tambourines. Same with pianos: you didn't play one piano, you played four.

"Actually, I played piano along with John on that track. Plus there was Gary Wright and Klaus Voorman. The only thing that Phil didn't do multiple tracks of were the drums themselves - I did one pass and that was it."

Well, Phil must've liked what you did because next you played with George Harrison on All Things Must Pass.

"The Wall Of Sound really came into play on that one. It wasn't talked about, but it just seemed necessary. People always ask me if my drums are doubled or tripled on that album and the truth is, they weren't. It was one performance, one take, boom! We were working so fast that I didn't have time to think - I just had to go with the flow of the music.

"We cut the whole thing in three weeks, which is amazing when you consider how much material is on the album. It was mostly the Delany and Bonnie band, which included Eric Clapton. A really good bond between the musicians existed during those sessions."

"I got really close to George making that record. He was so sweet and open-hearted. Each day he'd come into the studio and run down a new song, and we got to work cutting it. There was no mucking around.

"George probably did have more definite ideas of what he wanted from the drums than John - I think he knew that this was going to be a very important album for him, so he wanted everything to be just right. I was amazed at how many songs he had - he must've been stockpiling them for years!"

When you were tracking My Sweet Lord, did it occur to you that it sounded like He's So Fine?

"No! There was never any talk of it, nor did I think it bore any resemblance. I was so surprised when that lawsuit came down. When you listen to the two songs back-to-back, they're not that similar. Totally different songs, different meanings."

You joined Yes in 1972, but before this you played with John again on the Imagine album.

"Another beautiful experience. I remember when were cutting the song Imagine, John came in, sat down at the piano and played it, and we were all taken aback - 'Wow, that's really special!'

"I came up with what I thought was an appropriate approach to the song, nothing really complicated, but that's what the song called for. After three takes, we all kind of looked at each other and said, 'Hey, that's a keeper!' [laughs]

Jim Keltner played on some cuts, but you tracked most of the album.

"Yeah. Jealous Guy, Gimme Some Truth…I remember, before we cut Gimme Some Truth, I said to everybody, 'OK, we all have to be very angry.' [laughs]

"The song was such a direct political statement, there was no way we could play it lightly, you know? We had to attack it. I played a straight four on the verses on the floor tom and the snare and then on the angry parts I played four on the bar on the snare, along with a very sloshy hi-hat part. The drums had to really cut."

How did you feel about playing on How Do You Sleep? It was John's unabashed dig at Paul.

"John did something interesting before we cut that song: He gave all the musicians the lyrics and said, 'I want you to read these. You can decide if you want to play on it or not.' I looked at them and said, 'Yeah, sure, I'll play on it. Why not?'

"I knew what the song was about, but it was a great number. He was saying what he wanted to say. I certainly wasn't going to tell him what he should or shouldn't do. That wasn't my place."

Very soon after, you joined Yes. Did John or George ever offer their opinions on Yes' music?

"I kind of lost contact with John at that point. I was off touring the world and he was starting to get involved in his whole 'Lost Weekend' phase. But we did speak once several years later and he told me he was a big fan of Yes. He loved the band."

That's kind of surprising. One would think he would've considered Yes' music excessive.

"You would think that, sure. But John had a lot of sides to him, probably more than he showed a lot of people, at least publicly."

When was the last time you saw either John or George?

"Wow…I think the last time I saw George was in a club in London, right after we finished All Things Must Pass. John, the last time I saw him…actually, I played one last show with him at the Lyceum Ballroom in London. That was the last time.

"They were both beautiful guys, and I have to say, playing with them were certainly highpoints of my career. They got me started professionally. I owe both of them a great deal. I wish they were still around. The world lost a lot when they died."

In addition to Yes, when he can fit it into his schedule, White, a Seattle resident, also performs with that city's Beatles tribute group Apple Jam.

Joe is a freelance journalist who has, over the past few decades, interviewed hundreds of guitarists for Guitar World, Guitar Player, MusicRadar and Classic Rock. He is also a former editor of Guitar World, contributing writer for Guitar Aficionado and VP of A&R for Island Records. He’s an enthusiastic guitarist, but he’s nowhere near the likes of the people he interviews. Surprisingly, his skills are more suited to the drums. If you need a drummer for your Beatles tribute band, look him up.