A-Z of classic rock guitar

From Aerosmith to ZZ Top

Introduction

Music styles don’t come much wider, cooler or more inspirational than the behemoth that is classic rock.

Join us as we chart the biggest players, the most important techniques and landmark gear in the electric guitar’s most important genre...

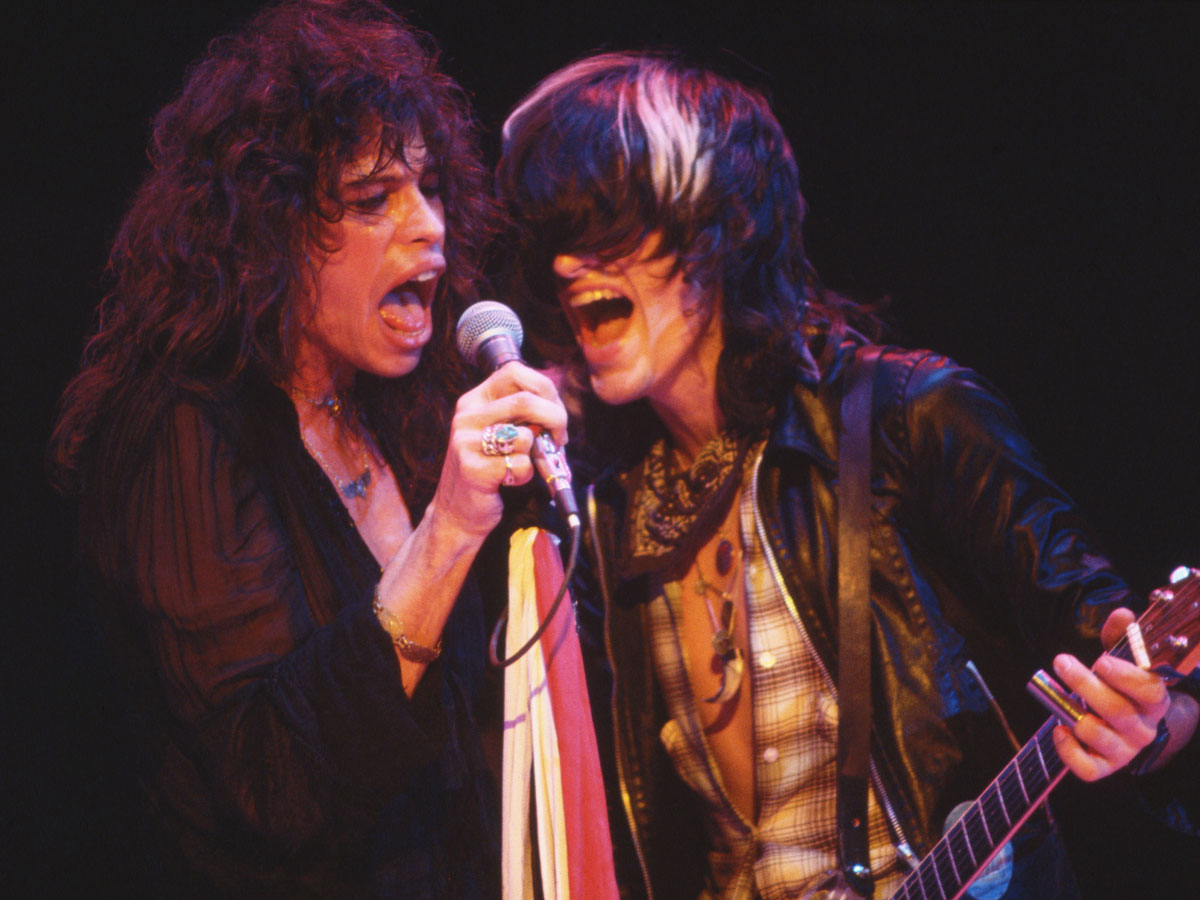

A is for... Aerosmith

We can’t think of many other iconic rock bands who have managed to be even more successful with their second crack of the whip after splitting up and going their separate ways. But then, Aerosmith are just a little bit special.

You may know them as arena-stomping rock titans with tongue-in-cheek anthems such as Dude (Looks Like A Lady) and Love In An Elevator, or even as trailblazers of the rap/rock movement with their Run-DMC collaboration, Walk This Way. But all of that came after the band’s second coming.

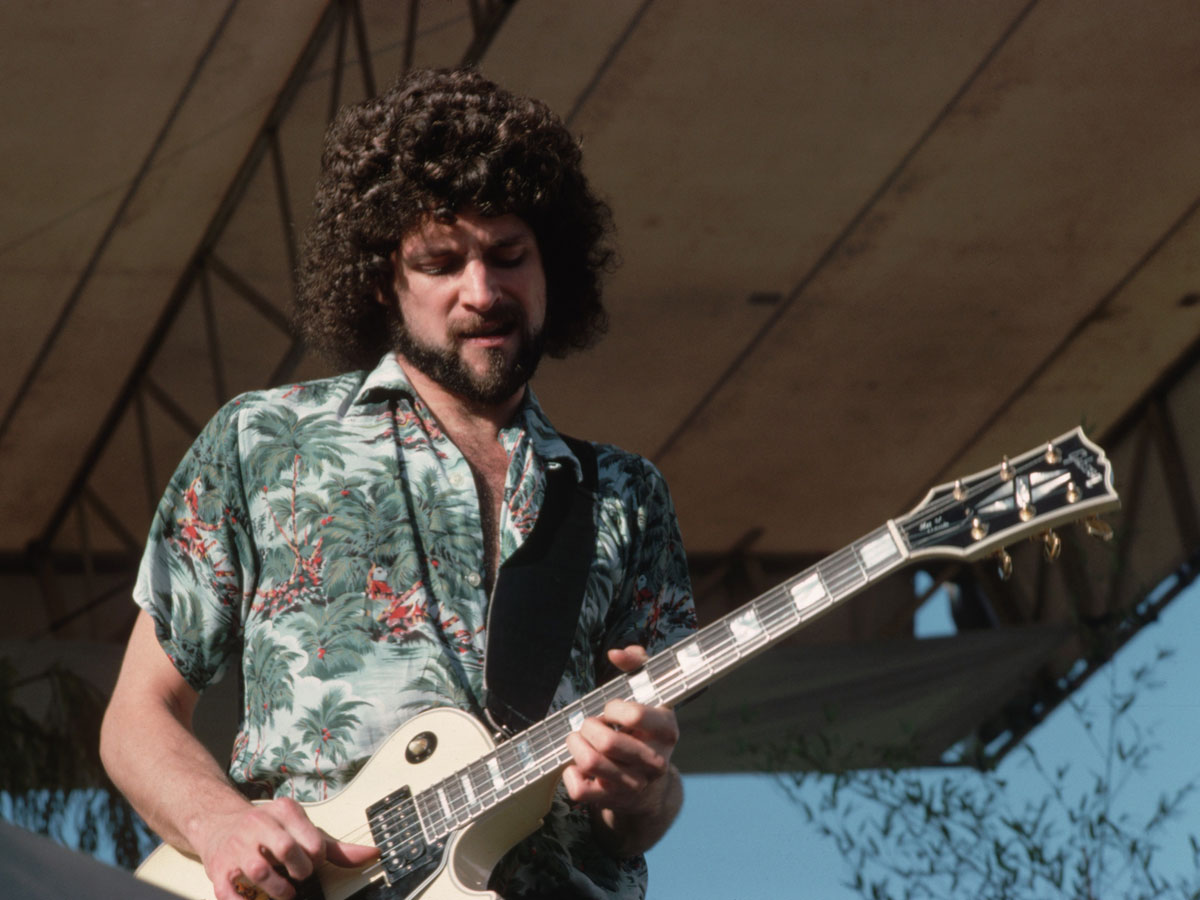

"Joe Perry and the consistently underrated Brad Whitford were blues-rockin’ barnstormers"

Back in the 1970s Joe Perry and the consistently underrated Brad Whitford were blues-rockin’ barnstormers with the added edge of embracing English rock influences; tickling a young Saul Hudson’s ears with their greasy licks before he became the Slash we love today.

As Perry told our sister magazine Guitarist in 2004, “We appreciate our roots - even though they wove their way from the Delta to Chicago, to London and Liverpool and back here to America.”

By 1975 and third album Toys In The Attic they were refining the blend, and 1976’s Rocks remains their classic album; helmed by the primal howl of Perry’s one-time Toxic Twin Steven Tyler with the band’s raw groove and interplay backing him every step of the way.

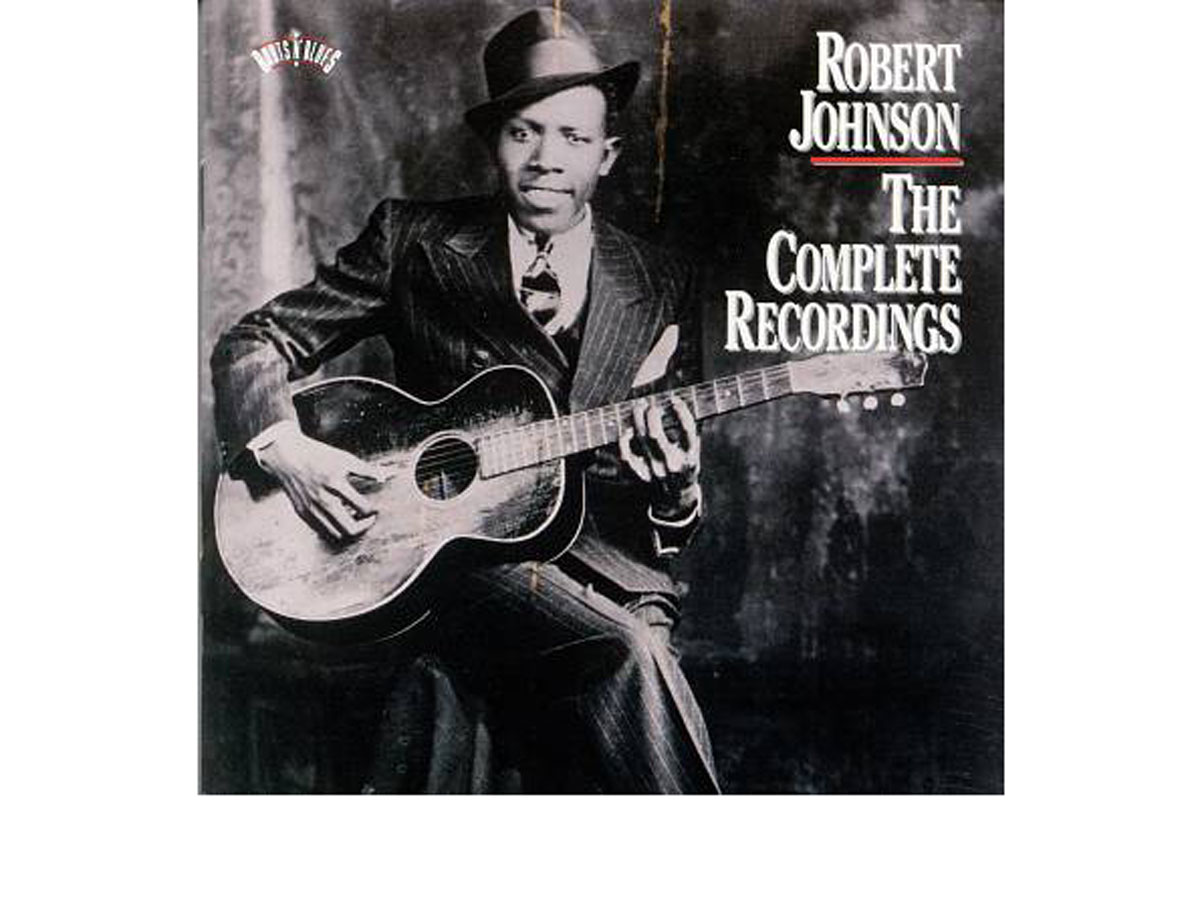

B is for... blues

Throw a stick in a 60s record shop and you’d have hit a future guitar god as he rifled through imported Blind Lemon Jefferson 45s.

In a pre-X Factor world, Britain’s pubescent rock hopefuls were all in thrall to the dusty, scratchy, haunted laments of the Delta dons, from Robert Johnson to Elmore James.

"This new generation played it harder, heavier and hairier"

The critical difference - exemplified by albums such as the Beano album (1966), Cream’s Disraeli Gears (1967) and Led Zeppelin I (1969) - was that this new generation played it harder, heavier and hairier, with Clapton noting that his studio approach was to crank an amp “as loud as it would go until it was about to burst”.

Rocket-fuelled blues covers were everywhere, from Zeppelin’s thunderous take on Willie Dixon’s I Can’t Quit You Baby to Cream’s spin through Skip James’ I’m So Glad.

Even when the rockers branched out into originals, it didn’t take a musicologist to spot the genre’s impact in the pentatonic-based soloing and 12-bar structures.

“I owe it to all of them,” reflected Jimmy Page this year. “The blues was an undeniable element of everything that was going on in Led Zeppelin. But when Led Zeppelin do a blues, it’s not like anybody else.”

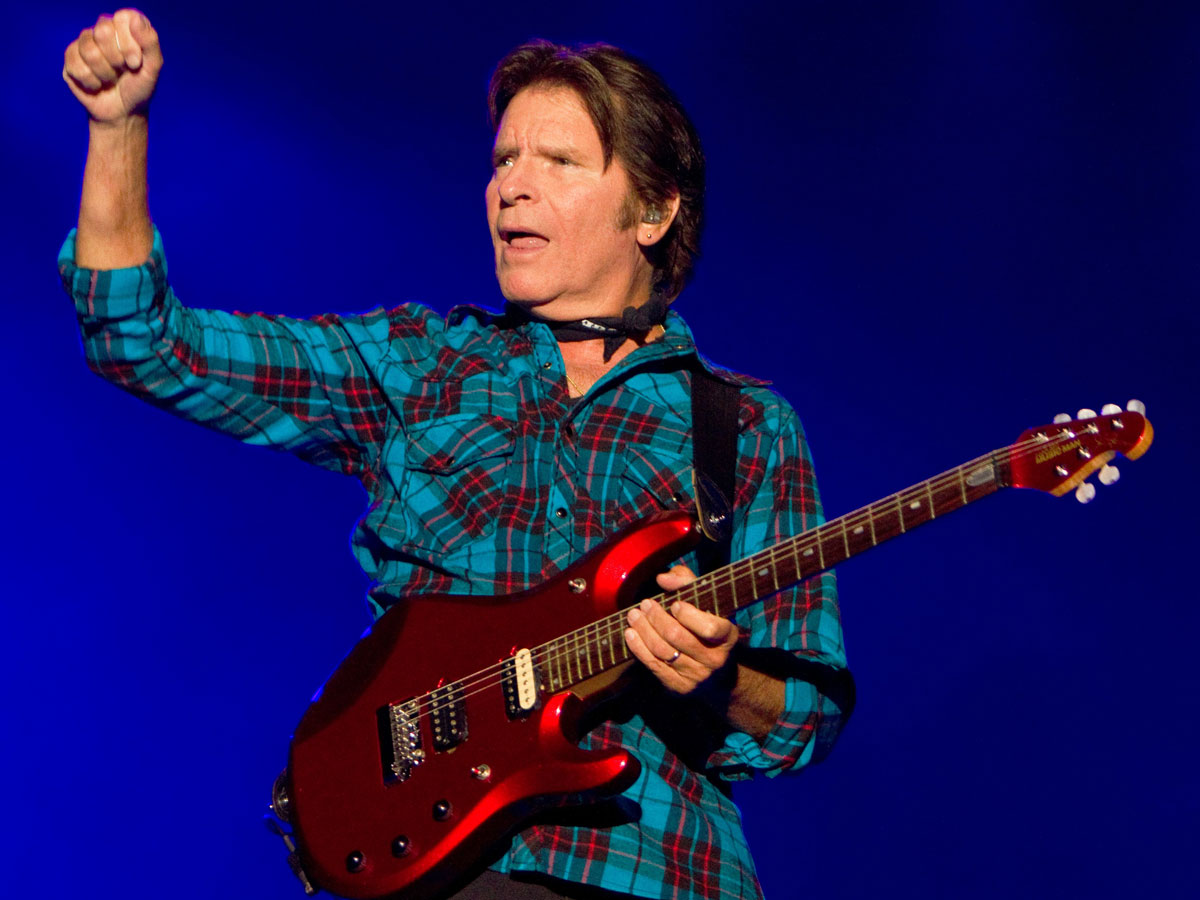

C is for... Creedence Clearwater Revival

Whatever John Fogerty was having for breakfast in 1969, we’d like some, please.

Creedence Clearwater Revival’s 22-year-old songwriter, guitarist, producer and manager wrote three albums of songs for the band that year (Bayou County, Green River and Willy And The Poor Boys), just part of a four-year, seven-album run for the remarkable American band.

"There’s a wealth of great music to be found in CCR’s legacy"

There’s a wealth of great music to be found in CCR’s legacy. You don’t have to look far beyond their titanic hits Bad Moon Rising and Proud Mary to discover that John and brother Tom were really onto something good; the songwriter was an Americana revivalist who bucked the ‘cool’ psychedelia of his time to channel his own roots heroes from Elvis guitarist and rock ’n’ roll pioneer Scotty Moore, to Delta bluesmen like Lead Belly and folk hero Pete Seeger.

The resulting lean but soulful Southern rock sounded like it had boogied straight out of a Louisiana swamp (even though the Fogertys were actually Californian).

They could be vitriolically political (Fortunate Son), poetically melancholic (Lodi, Long As I Can See The Light) and go toe-to-toe with any hard blues rockers on the planet. They could also play a mean cover: check out the band’s mesmerising 11-minute take on Heard It Through The Grapevine to hear John’s innate sense of lead expression in full force.

D is for... Deep Purple

Before he embraced the doubleneck lute and its associated minstrellian action, Ritchie Blackmore was a bona fide guitar god, who made smashing his Strat into a Marshall stack often the only logical conclusion that could follow his incendiary live performances with Deep Purple.

"Blackmore's work with Purple would have huge impact on heavy rock and metal"

Weston-super-Mare’s most famous son may have looked to Hendrix as his hero, but he brought plenty of his own chops to the feasting table with his band after time playing as a session man. His work with Purple would have huge impact on heavy rock, metal and even neoclassical instrumental virtuosos (Mr Malmsteen, please stand up).

Blackmore was writing meaner riffs than anyone else by the dawn of the 70s, but the kind of dynamism he forged with fellow maverick, organist Jon Lord - all the way through Purple’s tenures with three different frontmen - had never been witnessed in rock before.

They’d break out of their rhythmic and riff work for dogfighting solos that equally demonstrated their classical leanings and rock abandon to lift songs such as Burn, Speed King and Highway Star up onto a higher plain.

E is for... Eagles

Great songs, sublime harmonies and a singing drummer - blah blah blah.

Okay, if you’re still not sold on the Californian band from their hits, check out these lesser-known gems...

1. Tryin’

Album: Eagles (1972)

This three-minute poprocker could have been a Boston song with different production, and bucks the idea the early Eagles were a country rock proposition.

2. Bitter Creek

Album: Desperado (1973)

Think the Eagles are all about slick studio sheen? This is them stripped down acoustically to a vulnerable core, letting the vocal harmonies shine even brighter.

3. Out Of Control

Album: Desperado (1973)

There’s a surprising British glam strut to the heavy 12-bar boogie here.

4. Visions

Album: One Of These Nights (1975)

Don Felder sings his only Eagles lead vocal here, but the two solos are the biggest draw, featuring the twin-harmony work that would later immortalise Hotel California’s closing section the following year.

5. Journey Of The Sorcerer

Album: One Of These Nights (1975)

This symphonic banjo instrumental barely sounds like them at all, and more Jimmy Page’s vision than Gram Parsons. The TV, radio and film adaptions of The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy would later use it for its theme.

6. Teenage Jail

Album: The Long Run (1979)

The Black Eagles? Certainly the heaviest they’ve ever been. The doomy riff from Teenage Jail could easily have been an Iommi creation, and coupled with Frey and Henley’s harmonies, it adds up to a fascinating, eerie oddity with an excellent Frey synth solo before Felder lets rip, big time.

F is for... Fleetwood Mac

Acid trips, religious cults and affairs - there have been woes and misfortune as nine players have passed through the varying line-ups of Fleetwood Mac over the years, as they moved from British bluesers to stadium straddling American favourites. But here are three of the key players in their lineage.

Peter Green (1967-1970)

The Bluesbreaker

Green founded the band with drummer Mick Fleetwood and guitarist Jeremy Spencer, after initially replacing Eric Clapton in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers.

A prodigious blues talent with soulful vibrato, the Les Paul player (his famous ’59 ’Burst from the time, ‘Greeny’, is now owned by Kirk Hammett) expanded his songwriting horizons beyond the genre during his tenure with Mac.

He penned undisputed classics Oh Well, Albatross, Man Of The World and Black Magic Woman, later covered by Santana.

Danny Kirwan (1968-1972)

The Underrated

Peter Green was so impressed with a teenage Kirwan’s playing and vocals that he convinced the band to bring him into the fold to become a five-piece with three guitarists.

Kirwan’s precise, strong bending technique and powerful vibrato refl ected an emotional connection with guitar and he would share writing and vocal duties for 1969’s Then Play On.

He soldiered on with Spencer after Green retired from music, helping take the band beyond the blues to a more commercial rock, but was acrimoniously fi red on a US tour.

Lindsey Buckingham (1975-1987, 1997-present)

The Fingerstyler

The band became a very different proposition when Californian guitarist/ vocalist Buckingham and then girlfriend, Stevie Nicks, joined the ranks.

Within two years, they’d help create the multi-million seller Rumours and Mac became a global arena band. The fact that the writer of stone-cold classic Go Your Own Way is a self-taught fingerstyle player goes some way to explain his unique approach; he took his song literally.

There are elements of folk, bluesgrass banjo and flamenco technique with an interesting approach to blending in a piezo tone in with his sound, and huge feel in those wailing fingerpicked lead lines.

G is for... Guns N' Roses

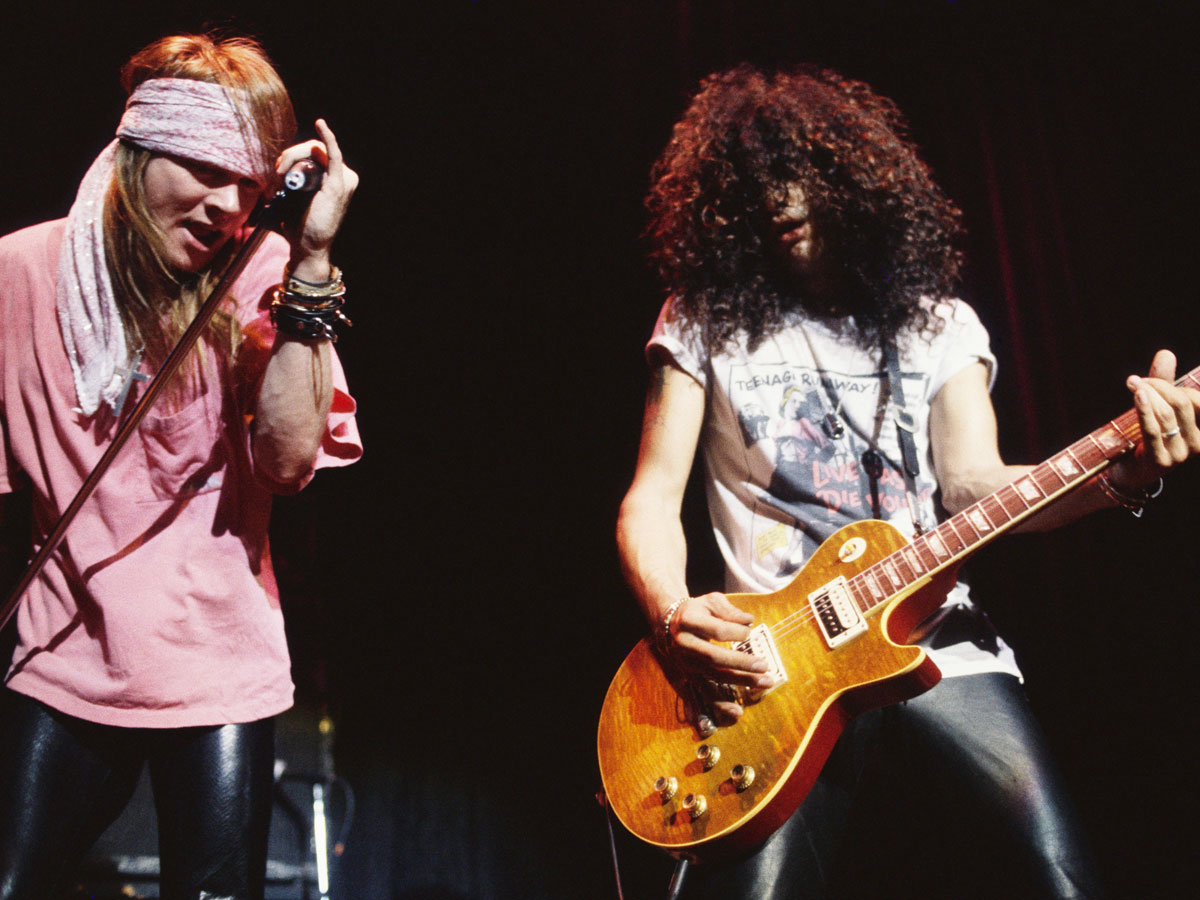

Just listen to Appetite For Destruction. As soon as Slash’s opening delayed line starts, you know you’re in for something special.

What follows is 51 minutes of life-changing rock that delivered one of the genre’s great guitar partnerships in Izzy Stradlin and Slash.

"Slash - reviving the guitar hero image with his low-slung Les Paul, top hat and half-smoked Marlboro - was only 21 when he recorded Appetite in 1985"

Then consider that Slash - reviving the guitar hero image with his low-slung Les Paul, top hat and half-smoked Marlboro - was only 21 when he recorded it in 1985.

Much has been made of the album’s guitar tone, with Slash rumoured to have used a non-Gibson clone of a ’59 Les Paul through modded Marshall JCM800, hired from SIR Studios. Both pieces of gear have since been replicated with the Gibson Appetite Les Paul and Marshall AFD100.

By the time 1991’s Use Your Illusion I and II rolled round, the dynamic had shifted as much as the excess. Izzy left during the world tour, followed by Slash three years later.

It’d be easy to dismiss GN’R after that, given the 15-year wait for Chinese Democracy, but let’s just think about the guitarists who have taken a desk at Rose Industries since then: Robin Finck, Buckethead, Paul Tobias and the current line-up of Richard Fortus, Bumblefoot and DJ Ashba.

Slash also continues to rock, and his solo career’s taken off since Slash in 2010. The smokes are gone, but the top hat and LP remain, and we wouldn’t want it any other way.

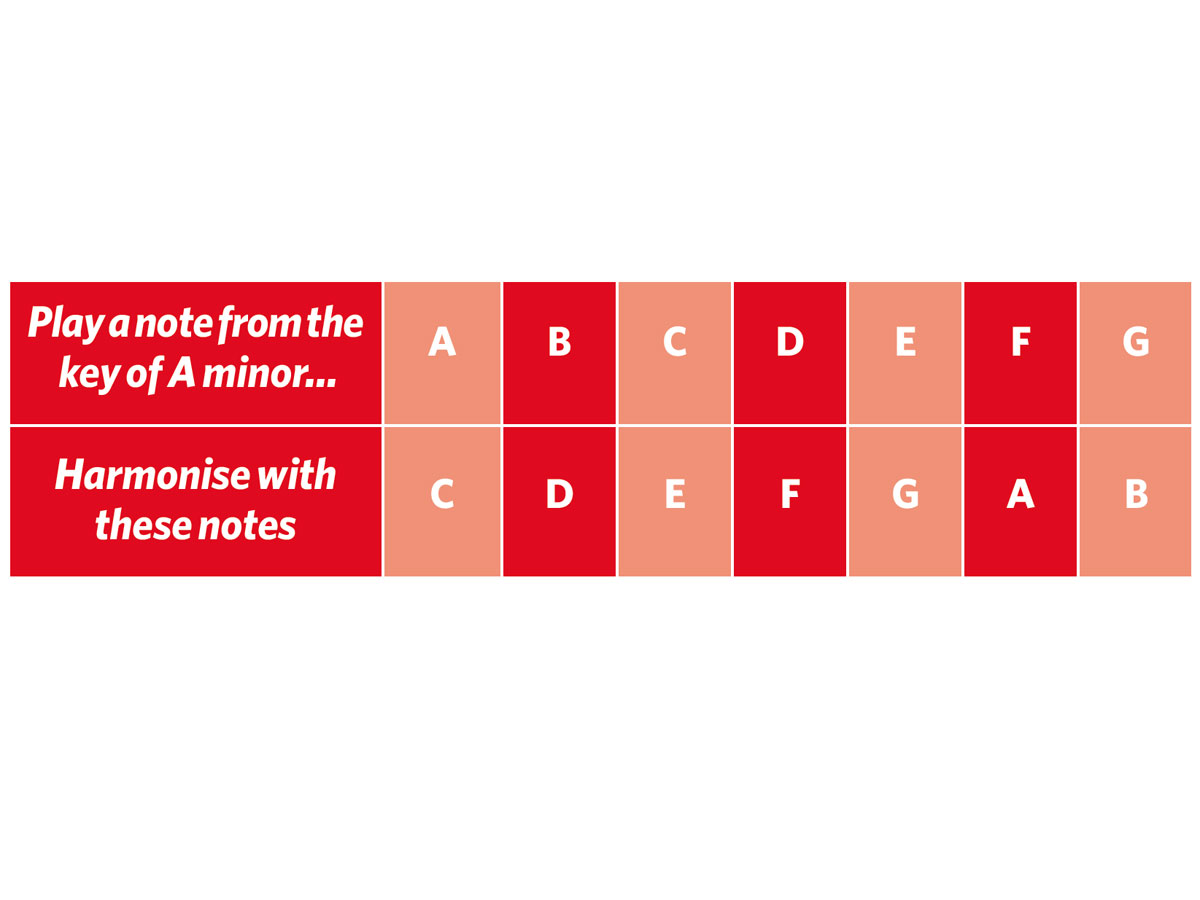

H is for... harmony lead

Harmony lead guitar was pioneered by bands such as Thin Lizzy and the Eagles in solos from The Boys Are Back In Town and Hotel California.

"To start harmonising your own solos, you just need to know the notes of the key signature you’re playing in"

Other key players are Iron Maiden, Wishbone Ash and The Allman Brothers Band. To start harmonising your own solos, you just need to know the notes of the key signature you’re playing in (we’ve used A minor). Oh, and a second guitarist…

The notes of A minor are A B C D E F G. When you play an A note in your solo, the second guitar should play C; when you play a B, harmonise with D; C harmonises with E, and so on. It is called ‘3rd harmony’ because the first note of the scale harmonises with the third, but 4th, 5th and 6th harmonies can sound great, too.

I is for... Tony Iommi

You know about the synthetic fingertips and the down-tuning, but here are five pearls of wisdom from the man himself on the creation of the heavy-rock guitar sound.

1. Hank Marvin inspired his darkness

“Hank Marvin - I like the sounds he was getting, the darkness in some of it. With Apache and Man Of Mystery, it created a dark image and I liked the sound. It was very important for me.”

2. Being The Only Guitarist Forced Him To Play ‘Big’

“Because I was the only guitarist, and there was previously always a rhythm guitarist in the different bands then. Everybody had to have a rhythm guitar then. But with us because we only had two guitars [including bass guitar] I was trying to get a bigger sound by making the bottom E ring by playing a chord, then Geezer would do the same to make that sound as big as it could be.”

3. A great riff is often a simple riff

“Well, a riff doesn’t have to be extremely technical to be great. Iron Man was a very basic thing. Something you can hum or whistle - memorable. You can get very complicated ones, but I don’t tend to go for them. I like the simpler ones you can remember.”

4. You need some light to be heavy

“I’ve always looked at it a bit like the calm before the storm. Certainly on the early albums, I’d do a little passage of something and then when the riff comes in it sticks out more. It just gives a bit of light and shade.”

5. It has to be an SG

“I like the shape, I like the size of it and I like the fact that you can get up to the top frets. With Les Pauls and stuff - I’ve got some Les Pauls - for me they’re not… especially as I took the ends of my fingers off, I can’t reach the top notes very easily. So the SG was ideal for me, as was the Strat.”

J is for... Jim, Jimi, Jimmy

Jim Marshall

The former drum teacher from London had a lasting influence on rock music. He designed his first amp in 1962, but it was three years later when, aided by The Who’s Pete Townshend, Jim came up with the idea of the stack.

It comprised the first Super 100 head and a gargantuan 8x12 cabinet, the latter soon sawn in half to make a pair of 4x12 cabs. It sounded and looked great, and it still does. Jim sadly died in 2012.

Jimi Hendrix

Such was Jimi’s influence that his unmistakeable technique and style can be heard everywhere. His influence is more obvious with the likes of SRV and John Mayer, but the chord voicings and phrasing Hendrix used are common throughout much of today’s guitar music.

His effortless control of a wailing Stratocaster still beggars belief, and his use of both feedback and lighter fluid captivated millions. We wish he were still playing today.

Jimmy Page

Led Zeppelin are among the biggest rock bands of all time, and their impact is largely down to a certain James Patrick Page.

He’s written more timeless rock riffs than just about anyone else and it’s still difficult to comprehend that he came up with Whole Lotta Love, arguably the greatest of them all, in 1969. Even the merest glimpse of a Gibson EDS-1275 double-neck, let alone a late-50s Les Paul, evokes Pagey. A true living legend.

K is for... KISS

1. They’re your favourite guitarists’ favourite band

For American kids growing up in the 70s, it was all about KISS. They were massive on a truly global scale and millions took the KISS mantra to their juvenile hearts: having a good time, women, blowing things up and shouting it out loud. Still not convinced?

You can’t get three cooler guitar players than Dave Grohl, Dimebag Darrell and Slash, and each of them would chat at length about the first time they saw KISS live, the first time they met guitarist Ace Frehley and how much the music means to them. And remember: what Slash says goes.

2. The songs

KISS could mix three-chord punk ideals with melodic hooks sufficiently weighty to snag a whale, and adding four distinct personas into mix meant they just couldn’t fail.

The lyrics were great fun, with barely concealed double entendres littering every couplet and chorus. Love Gun? We’ll leave that one with you, but rock anthems don’t come much bigger than Rock And Roll All Nite.

3. The guitars

Each of Paul Stanley’s axes are swathed in mirrors, be they cracked or part of the scratchplate, while Ace Frehley had a light-guitar that flashed on and off from within.

He also worked out how to get his three-pickup Les Paul to not only spontaneously combust, but also fire rockets from the headstock.

When the band launches into Shock Me, you know it’s coming, but you’ll scream like a kid when the first rocket smashes into the lighting rig. We did.

4. The stage show

From the very beginning of their career, it was all about the live show.

Even today, KISS provide the ultimate live rock experience that includes levitating drum risers, flying band members and a lighting truss shaped like a spider. Add in more pyro than Bonfire Night and you’re certain to have a good time.

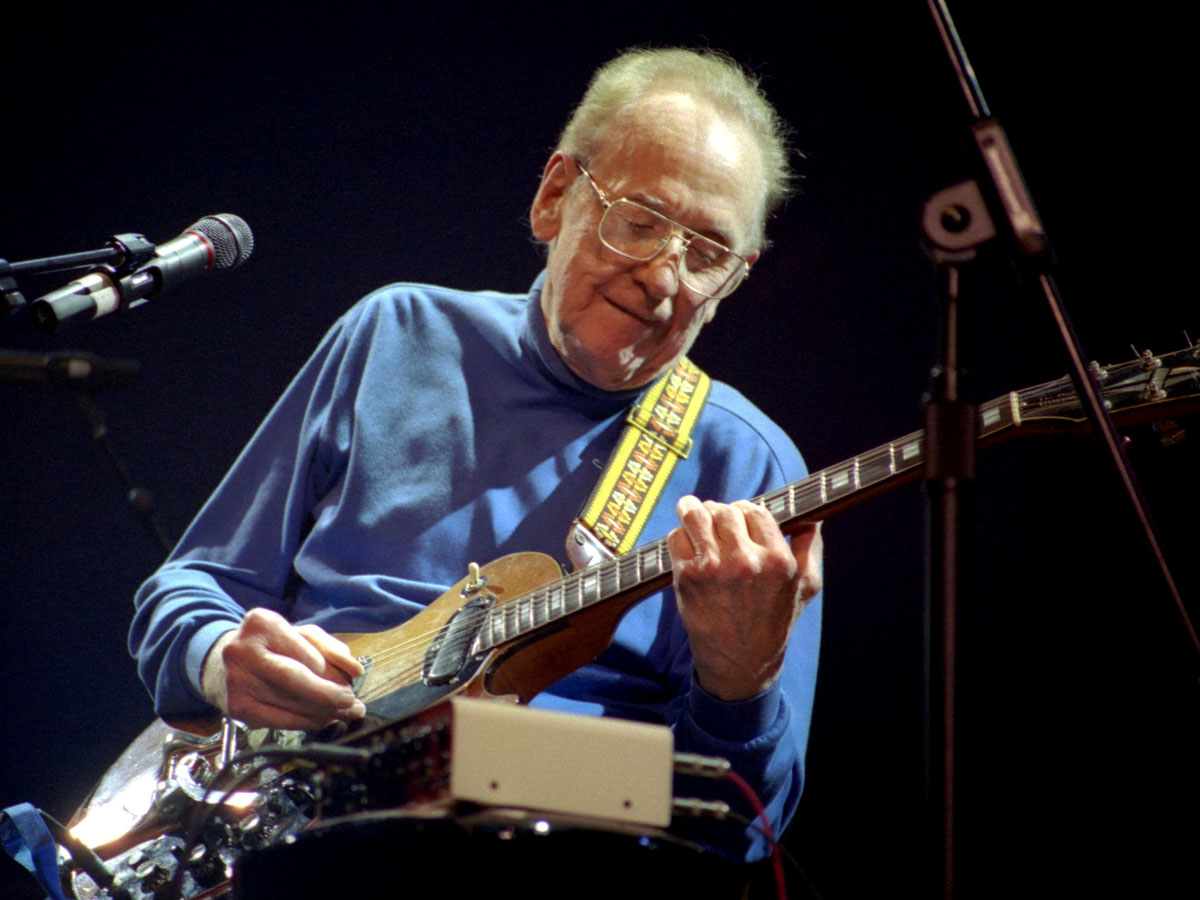

L is for... Les Paul (the man and the guitar)

Few things scream ‘classic rock!’ louder than a Les Paul and a Marshall, and it’s easy to forget that the most iconic rock guitar is actually a signature model.

In 1950, the Fender Esquire had created a brand-new market for players who wanted to perform loudly. By way of a reaction, Gibson - who had previously rejected Les Paul’s ‘The Log’ solid design in the 40s - enlisted Les to work with Gibson’s Ted McCarty to create a solidbody guitar. The ‘Les Paul’ model was born.

"As well as giving us the guitar that bears his name, Les contributed hugely to the progression of music technology"

Luxurious by comparison to Leo Fender’s design, the Les Paul feature a trapeze tailpiece and McCarty’s P-90 pickups, offering a thicker sound than Fender’s standard single coils, while the top was adorned with a gold finish.

The Les Paul went through a few changes over the next six years, before becoming what we know as the classic-rock machine today. 1954 saw the addition of the tune-o-matic bridge and tailpiece, 1957 brought Seth Lover’s PAF humbucking pickups, and in 1958 the first Sunburst Les Paul Standards were released.

A year later, these revisions converged with a thinner neck profile and jumbo frets to create what has become the Holy Grail of rock guitars: the ’59 Les Paul Standard.

Gibson is thought to have produced anything between 650 and 1,900 Sunburst Standards in 1959, and this critical mass of design has made a ’59 ’Burst one of the most sought-after guitars on the planet.

As well as giving us the guitar that bears his name, Les contributed hugely to the progression of music technology. His experiments with ‘sound on- sound’ recording via disc-cutting lathes in his garage helped give birth to multitrack recording, plus he invented tape echo by modifying magnetic tape machines along the way!

Les sadly left us in 2009, but the legacy of Lester William Polsfuss will resonate throughout music forever.

M is for... Gary Moore

By the time of his Les-Paul-and Marshall-driven high-octane reinvention of the blues on 1990’s Still Got The Blues, virtuoso Irish guitarist Gary Moore had already accrued 20 years of thoroughbred rock pedigree.

"Gary’s impact and legacy reach farther than pure blues"

Following stints with Irish blues-rockers Skid Row in the early 70s, Gary joined fusion act Colosseum II (he always had the lead chops to cut it with the jazzers) and toured with harmony-lead legends Thin Lizzy, eventually recording on the band’s acclaimed 1979 album Black Rose: A Rock Legend. Blues-rock, modal fusion or melodic twin lead... Gary could do it all.

With this high-profile leg up into the mainstream, Gary pursued his solo career and in 1978, breakthrough single Parisienne Walkways hit the streets - a live favourite famous for Gary’s ‘infinite’ sustain (he’d locate the feedback sweet spot during soundchecks).

In the 80s, a commercial rock and heavy metal turn showcased Gary’s technical skills at new levels. He’ll likely be remembered for his later work as the consummate blues guitarist, but with technical whizzes Paul Gilbert, Gus G, Zakk Wylde, Kirk Hammett and Randy Rhoads all citing his influence, Gary’s impact and legacy reach farther than pure blues.

N is for... new blood

The last decade has seen a resurgence of new bands influenced by classic rock carrying the torch into the 21st century. Here are three of our favourites.

Rival Sons [pictured]

One of the best in the ‘new breed’ is Rival Sons. Sounding like an audio equivalent of the retro filter on Instagram, Scott Holiday’s riffing, chord pushes and wah-tinged solos are matched with a taste for classic hardware, from Firebirds to Jazzmasters and NOS-looking Fano guitars.

The Temperance Movement

UK blues-rockers The Temperance Movement - with guitarists Luke Potashnick and Paul Sayer - fuse everything that’s good in classic-rock guitar, from bluesy melodies to groove-laden country picking and Hendrix’s chordal rhythm style. Their self-titled debut is a masterclass in tone and tasteful technique.

Royal Blood

2014’s biggest new rock band, Royal Blood, came from outta nowhere (Brighton, actually), and out-riffed the world with a bass. Mike Kerr’s pitch-shifted low-end riffs earned them critical praise, a No 1 album and heavyweight celebrity fans like Dave Grohl, Lars Ulrich and Jimmy Page.

O is for... odd time signatures

From the 7/4 vamp of Pink Floyd’s Money to the deceptively tricky 11/8 part in Here Comes The Sun, to the fluid timings in Led Zep’s Black Dog, classic rock - and its modern derivatives - is steeped in odd time signatures.

Far from the contrived bean-counting of prog, though, these odd meters are often implemented with a groovy looseness that seamlessly catches the listener unaware.

"Thankfully, stepping out of the 4/4 march is not as hard as you might think"

Thankfully, stepping out of the 4/4 march is not as hard as you might think. It’s just a case of knowing how many beat subdivisions there are in a bar of music. For example, 4/4 means four crotchets (quarter notes) to every bar.

A bar of 3/4 only lasts for three quarter-note counts, while a bar of 5/4 lasts for one extra. Not all music is evenly divided by crotchets; some tracks have additional or fewer crotchets, quavers or semi-quavers, which is why you end up with complicated-sounding time signatures like 11/8. Here’s the easy way to work one out...

1. Listen

If you’re stuck trying to work out what time signature you’re in, the first thing to do is listen out for the start and end of a repeating phrase.

It’s fine to go by feel at this point; listen to notes and accents that stick out to help you. Once you know where the passage starts and ends, it’s on to the next step.

2. Tap

Now, you need to find out the note value that each bar is divisible by (4, 8, 16, etc). Try tapping to the natural pulse of the song from the start to the end of the phrase.

Does the phrase repeat on a down-beat? If so, move on. If not, try tapping a smaller division (twice as fast) until the phrase repeats on a ‘tap’.

3. Count

Sounds silly, but that’s all there is to it. Once you’re locked in with the loop points of your phrase, it’s just a matter of figuring out how many taps of the division you’re using it takes before the loop starts again. So, if you’re tapping eighth notes and the phrase repeats after seven of them, you’re in 7/8.

P is for... pentatonics

We don’t think we’re exaggerating when we say that rock guitar might not even be a thing without the minor pentatonic scale and its close relative, the blues scale.

Whether you’re playing ballsy, low string ear-worm riffs or blazing solos that melt faces, some combination of minor pentatonic scale notes is bound to fit your needs. Need evidence to support these claims? How about riffs from Layla, Black Dog, Purple Haze and Back In Black?

Seriously, don’t get us started on lead - Tony Iommi, Eric Clapton, Angus Young, Jimmy Page, Joe Perry and Slash have all spent most of their careers soloing with this scale.

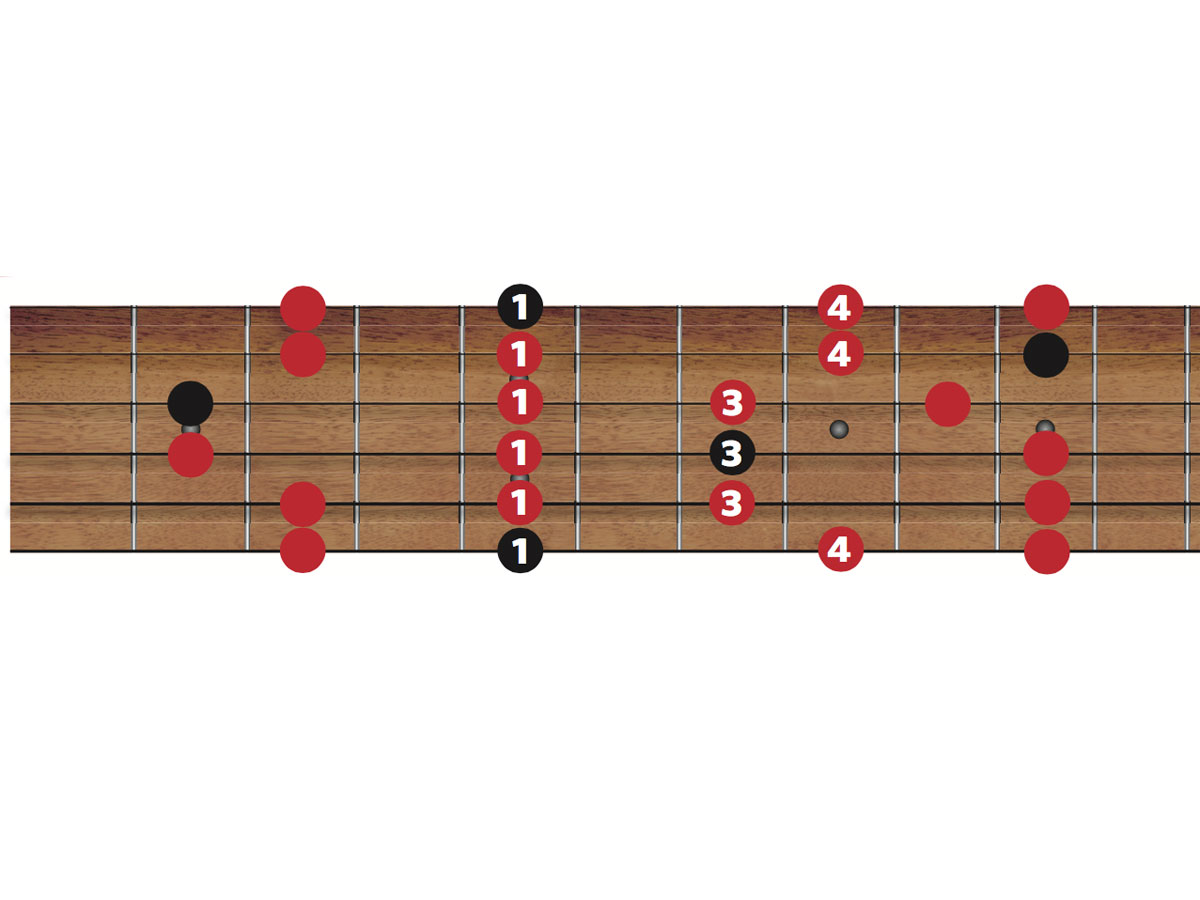

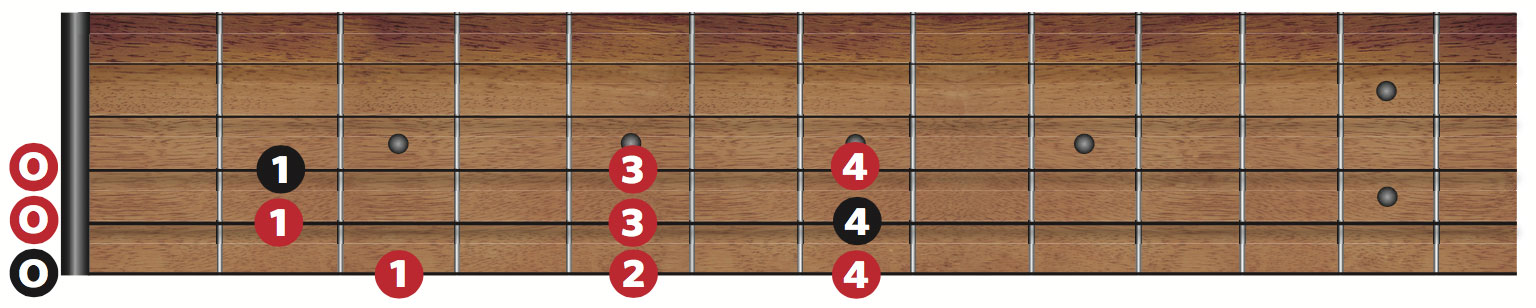

If you need a shortcut, use the next shape shown here as a framework for riffing and the second shape [above] for lead playing.

Riffing with the E minor pentatonic scale

This set of notes is ideal for low-string riffs in E minor. Move the whole shape over to the fourth and fifth strings and you’re in another guitar-friendly key of A minor.

Soloing with the E minor pentatonic scale [pictured above]

The main shape is the well known E minor pentatonic scale in 12th position. Use your first, third and fourth fingers to play it (remember, black dots are root notes).

Make up your own lead ideas with this shape and use the blank dots as a pool of extra notes (also from the E minor pentatonic scale) to extend your licks across the fretboard.

Q is for... Queen

Queen are one of England’s most successful and revered bands, and while the focus has often been on the flamboyant Freddie Mercury, it’s Brian May who’s the cornerstone of the band’s unique sound.

"May'siconic guitar solo in Bohemian Rhapsody? “I could just hear it in my head,” he says"

He forged his way to the top using a guitar he and his father designed and made, from scratch, in 1963/’64. Using a treble booster to send a Vox AC30 into overdrive heaven, he utilises a sixpence as a pick to add colour to what would otherwise be a rather indistinct tone.

He also came up with the idea of using delays to play three-part harmonies with himself on stage, something that no other guitarist has done.

However, it’s his technique that demands the most attention. His clever use of emotive vibrato, unusual scales and differentpickup selections sets him apart - and his iconic guitar solo in Bohemian Rhapsody? “I could just hear it in my head,” he says. Clever clogs...

R is for... Rolling Stones

It’s hard to imagine any rock band, at any point in history, having more mojo than The Rolling Stones circa ’68.

Having got the early R&B covers out of their system, this was the moment when British rock’s deathless national treasures hit an imperious run of form.

"During a four-year hot streak, the 'Stones spat out Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers andExile"

During a four-year hot streak, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards’ songwriting partnership spat out Beggars Banquet, Let It Bleed, Sticky Fingers and the splendidly seedy Exile On Main Street, giving us the songs that punters sing in stadiums to this day.

Granted, founding guitarist Brian Jones’s tragic 1969 drowning wasn’t in the script. Yet Keef rose to the challenge, introducing the open tunings that drive classics such as Honky Tonk Women and Brown Sugar, ditching the sixth string, layering and capo-ing like a bastard, and hooking up with the eternally underrated Mick Taylor to perfect the push-pull twin-guitar interplay that he dubs “the ancient art of weaving”.

Not bad for a man who was dosed up to the eyeballs on heroin at the time. “I did Exile... when I was heaviest into smack,” the Human Riff once reminded us. “And that was a fucking double album...”

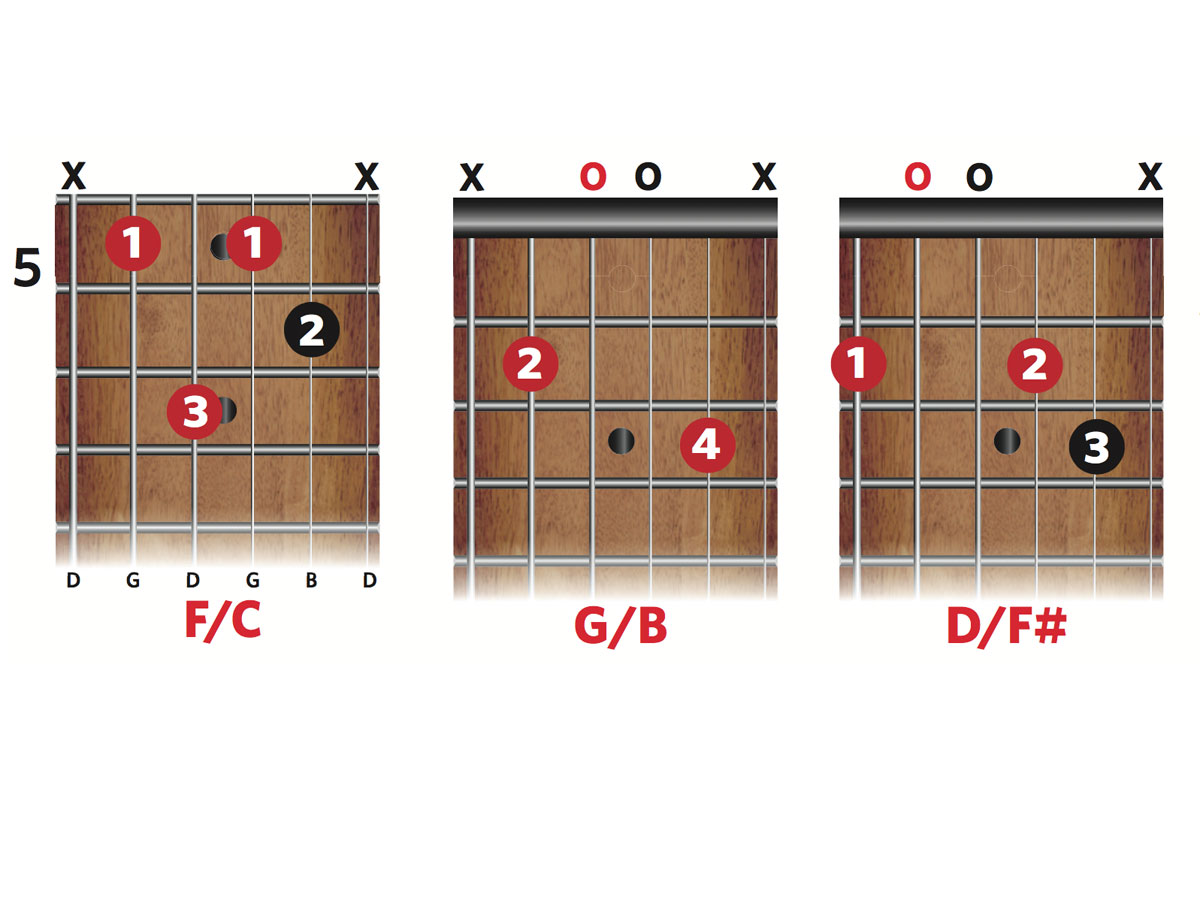

S is for... slash chords

Slash chords are all over many a classic-rock belter, and they probably cause more confusion among guitarists than any other type of chord, most likely because the way they are written suggests two possible chord names (try D/F# or A5/G, for example).

"Aslash chord is a chord that has a different bass note instead of the root"

The explanation is actually very simple: a slash chord is a chord that has a different bass note instead of the root.

So, D/F# is a D chord over an F# bass note. A5/G is an A5 chord over a G bass note. It’s easy to experiment and come up with your own slash chords and you may just find those ordinary open shapes gain new life once you’ve slashed them up over new bass notes.

T is for... tone

In the days before technology allowed musicians to get into every single nook and cranny of a recording, players had to be on the button in the studio.

That included getting their sound and equipment together and, as such, many classic-rock songs owe their fame to the tone of the guitarist in question. Here are just two for you to try...

"Van Halen’s ‘brown sound’ is responsible for turning many a guitarist’s head"

Van Halen’s ‘brown sound’ is responsible for turning many a guitarist’s head and, in the days before dual-cascading preamps, he simply turned his 1967 100W Marshall head up all the way. He also hooked up a Variax, a device that lowered the voltage that was going to the amp, thus causing it to go into a fat power-tube overdrive rarely attained previously. Check out the whole of Van Halen I or Mean Streets from 1981’s Fair Warning for aural proof.

Eric Clapton used a specific setting on his Gibson SG to create his famous ‘woman’ tone. Most famously heard on Cream’s Sunshine Of Your Love, Eric manipulates the guitar’s pickups and controls to create his thick, wailing overdrive sound.

U is for... unsung heroes

1. Terry Kath, Chicago

Hear: Chicago II (1970)

WHY? Hendrix once told Chicago’s sax player, “You guitar player is better than me.” Kath tragically died in 1978, aged just 31, but in his time he had serious chops that incorporated jazz, bebop and funk into his rock.

2. Buck Dharma, Blue Öyster Cult [pictured]

Hear: Secret Treaties (1974)

WHY? Buck could shred through a Fender Twin before shredding was even a description for guitar playing, and he’s been doing it with taste for years now.

3. Frank Marino, Mahogany Rush

Hear: Frank Marino And Mahogany Rush - Live (1978)

WHY? A true players’ player. Marino burns blues-rock pentatonics fast, but without ever losing feeling; the results are powerful.

4. Vito Bratta, White Lion

Hear: Big Game (1989)

WHY? White Lion didn’t change the world with their hair-rock, but before he retired unexpectedly from music, Vito was capable of recording rhythm and solos together in one single take. And how those solos sang.

5. Audley Freed, Cry Of Love

Hear: Brother (1993)

WHY? A former member of the Black Crowes, Freed has played with Joe Perry and Peter Frampton, but his own 90s band channeled Skynyrd and Free. His slinky licks really deserve to be enjoyed by more guitar fans.

V is for... Van Halen

One minute and 43 seconds. That’s how long it took for Eddie Van Halen to change rock’s trajectory and put the old guard against the wall.

As the second track on the California band’s self-titled 1978 debut, Eddie’s belief-beggering solo spot Eruption was short but earth-shattering: a technical showcase that announced the next evolutionary step for the human finger.

"Eddie’s belief-beggering solo spot Eruption was short but earth-shattering"

Divebombs, warp-speed tapping triads and quicksilver legato made the 60s gods sound like tortoises (even if EVH was an unabashed disciple, admitting that he got the tapping concept from Led Zeppelin’s Heartbreaker solo and citing Townshend, Hendrix, Clapton, Page and Beck as “five unique mothers”).

If Eddie’s chops tore up the rulebook, then jaws dropped a further few inches at the anarchy of his gear. In a world of vintage Les Pauls, the Van Halen sleeve introduced the Frankenstrat that kick-started the DIY craze.

From there came the Kramer 5150 that powered 1984, the Peavey amp of the same name (that lives on under EVH’s own brand) and the effects that together created the near-mythical ‘brown sound’.

The revolution had repercussions. Soon, EVH clones were everywhere, leading directly to the overblown pomp-rock scene that fully deserved to be punctured by grunge. Even so, Eddie Van Halen gave us the most thrilling ground zero for the electric guitar since Hendrix.

W is for... windmill (and other stage moves)

If you're an indie thumbsucker, it's probably sufficient to stare at your Converse while joylessly fretting a barre chord.

"The Who man managed to impale his hand on the whammy bar at a 1989 show in Washington"

Classic rock has always demanded a little more razzmatazz, with a slew of showboaters pushing beyond the mere application of finger to fret. Chuck Berry's duckwalk and The Shadows shuffle set a genteel standard in the 50s, but it was the posers of the 60s and 70s who patented the best stage moves, with Hendrix chowing on his Strat, Pete Townshend slithering across the stage on his knees and Angus Young spasming like a swatted bluebottle.

If you're too wary of knocking out the front row's teeth to attempt the whirligig (that is, spinning your guitar around your body on the strap) then make like Townshend and try the windmill, revving your strumming arm like Tyson on tartrazine, and clanking a chord on each cycle.

That said, you might want to take it a bit easier than the Who man, who managed to impale his hand on the whammy bar at a 1989 show in Washington, and admits it’s a painful ritual at the best of times: “Flesh flies off. Blood runs under my fingernails. When I windmill, I fucking windmill, right...?”

X is for... cross-overs

Yeah, we know it’s cheating but we don’t want to talk about xylophones. From the earliest of days, classic rock has always been a huge melting pot of styles, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

"Skynyrd brought country to the mix, and Aerosmith proved rock can rap"

Clapton, Hendrix and pretty much every guitarist ever since incorporated blues, GN’R punked it up at times, while Journey added jazz.

Skynyrd [pictured] brought country to the mix, and Aerosmith proved rock can rap with their joint reprisal of Walk This Way with Run-DMC, some would say paving the way Run-DMC and Aerosmith: keeping it real in 1986 for Kid Rock’s Skynyrd (and Warren Zevon-sampling) All Summer Long.

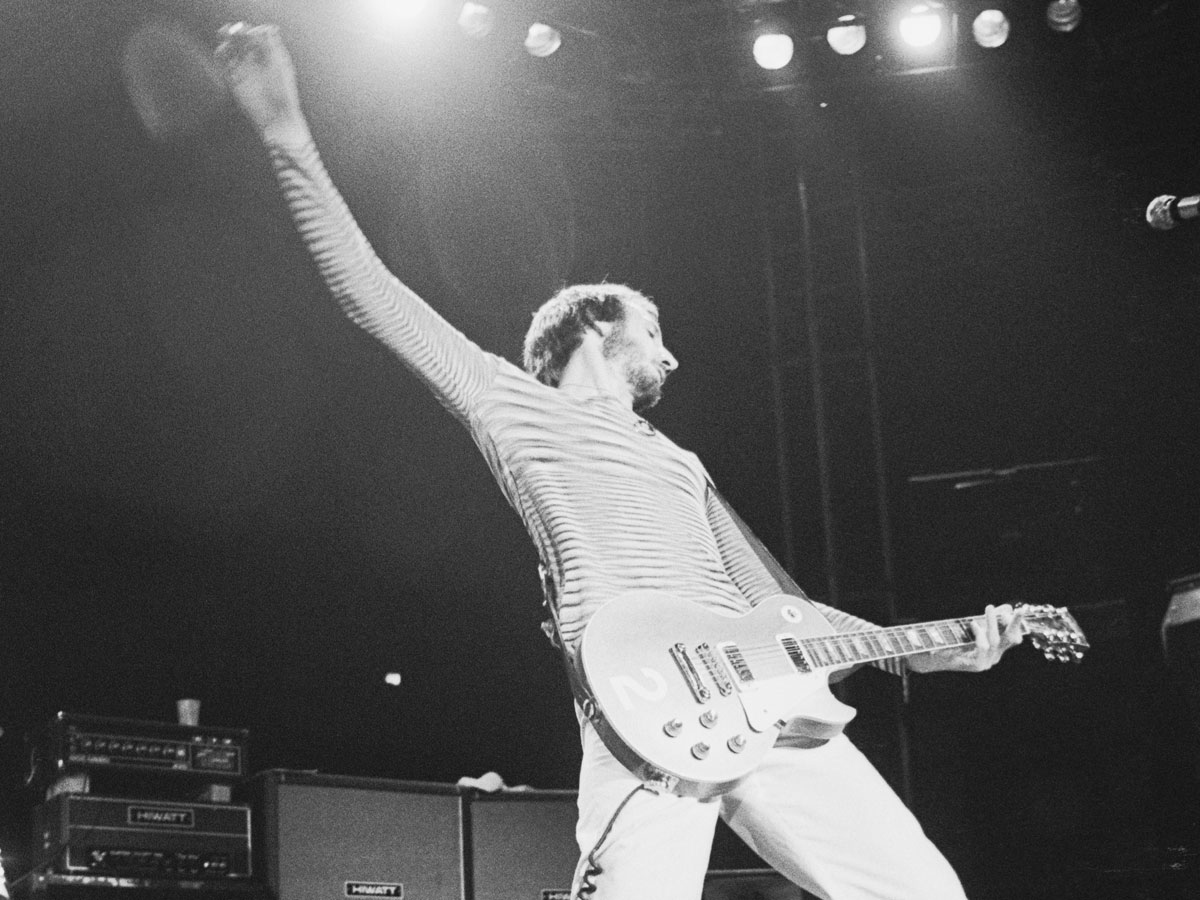

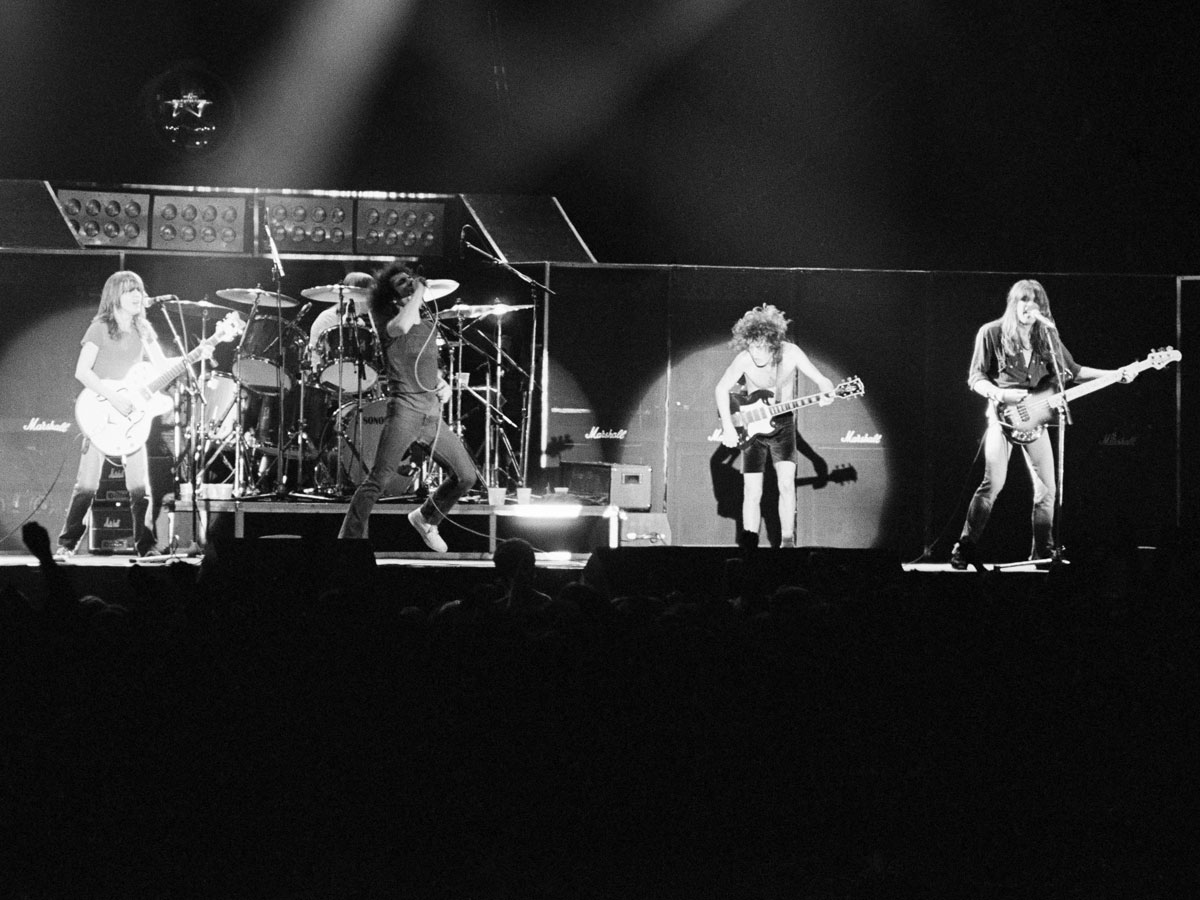

Y is for... The Young brothers

On a fateful day in 1973, Malcolm Young decided that his lead-guitar duties were interfering with his fun, and relinquished the role to his kid brother, Angus. So was born the greatest guitar tag-team in rock history - albeit one built on an unlikely chemistry.

"Mal was the engine-room who brought inimitable swing and muscle to deceptively simple riffs like Back In Black"

Shunning the spotlight to punch out airtight rhythm on his Gretsch Jet Firebird, Mal was the engine-room who brought inimitable swing and muscle to deceptively simple riffs like Back In Black and Shoot To Thrill (“He’s got the best right hand in the world,” noted Angus of his older brother. “I’ve never seen anyone handle the instrument like that, not even Keith Richards”).

With that bedrock in place, meanwhile, Angus was free to go batshit crazy, spitting out hyperactive blues-based leads on his 1968 Gibson SG and skedaddling across the stage like there was a hornet in his school shorts.

Last year’s announcement of Malcolm’s retirement due to dementia was the cruellest of ends to a partnership that pumped a million fists, and though AC/DC roll on with the excellent Stevie Young replacing his uncle, there won’t be a fan in the house who doesn’t feel the absence of the band’s lynchpin and de facto leader. We salute him.

Z is for... ZZ Top

Although the Texan trio had been peddling their unique brand of down ’n’ dirty blues since 1969, it was 1983’s Eliminator album and videos that sent them stratospheric.

"It was the sheer tone emanating from the impossibly cool guitars of Billy Gibbons that caught our ears"

As well as the songs, the beards and the fact that drummer Frank Beard had a naked chin (oh, our sides...), it was the sheer tone emanating from the impossibly cool guitars of Billy Gibbons that caught our ears.

Strangely, it’s a little tricky to get into the ins and outs of Billy’s gear, but things such as his now retired ’59 Gibson Les Paul, named Pearly Gates, a Gibson Explorer covered in white fur, and the Lap-Dog Of Distortion, featuring six Bixonic Expandora pedals for extra juice, are the stuff of legend.

He also uses skinny gauge-seven strings, plus a Mexican peso for a pick, and the resulting wonderfully harmonic- laden, fat tone comes from God himself.

Chris has been the Editor of Total Guitar magazine since 2020. Prior to that, he was at the helm of Total Guitar's world-class tab and tuition section for 12 years. He's a former guitar teacher with 35 years playing experience and he holds a degree in Philosophy & Popular Music. Chris has interviewed Brian May three times, Jimmy Page once, and Mark Knopfler zero times – something he desperately hopes to rectify as soon as possible.