A history of nylon-string guitars

From cat-gut to chart top

Introduction

For many of us, the nylon-string guitar was the cheap one you dispensed with as soon as you got your hands on some steel. Perhaps it’s time to think again: join us on a whistle-stop tour of nylons to date, and see if you might have room in your life for something truly wonderful.

We have World War II to thank for the nylon-string guitar, or at least its nylon strings, which first appeared in 1948 after a wartime shortage of ‘catgut’. Feline fans stand easy; it was in fact a material made from cattle and sheep intestine that had been used previously for the classical guitar strings. The guitar bit, of course, goes back a lot further...

Back to Torres

Antonio de Torres (1817-1892) is referred to as the ‘father’ of the modern classical guitar. He turned the smaller-bodied instruments of the day - that had begun to resemble what we now recognise as the guitar from around 1500 - into the basis for the modern classical instrument.

By the early 1850s his concert guitars were approximately 20 per cent bigger and, anecdotally at least, based on the figure of a young women he saw in Seville. Romance was a fundamental part of the classical guitar from the off.

Back to the facts, Torres certainly created the domed top and fan bracing that forms the basis of the instrument as we know it today, along with a bridge design that featured a separate saddle, as well as an overall austerity in decoration.

Those of us who are generally obsessed with electric guitars might assume that all classical guitars are the same, in a similar way that the untrained eye might assume all violins are identical.

But from the Torres ‘blueprint’ the great makers of the 20th Century - Ramíerz, Hernádez, Bouchet, Rubio, Hauser, Kohno, Fleta and many more - added their own style and techniques, creating often very different instruments in terms of feel and response.

Hitting the pit

As the classic guitar repertoire expanded, thanks in part to Andrés Segovia, the guitar became a solo ‘orchestral’ instrument, presenting classical makers with the same dilemma as steel-string and archtop makers: how to increase volume and projection? It’s a challenge that continues to this day.

In today’s classical world, the guitar remains very much acoustic, and aesthetically at least, the guitars tend to closely resemble those of 150 years ago. Yet modern makers such as Greg Smallman, for example, are still pushing the design, in his case using a thick solid-wood back and sides and a ultra-thin top braced with a lattice of carbon-fibre and balsa wood. They can be as heavy as a Les Paul but they certainly project.

It’s the guitar of choice for current classical poster-boy Milos Karadaglic who, at the time of writing, has three albums in the UK Classical album chart: Latino, The Guitar and Aranjuez that in combination have been there for the past 210 weeks.

A name many more of us will know, John Williams, has had his Spanish Guitar Music album in the chart for 185 weeks. Some would say the classical guitar is doing just fine. And let’s not forget the world of Flamenco, which uses a subtly different version of the classical guitar and has produced some of the most explosive and expressive music created on the nylon- string: just check out the late legend Paco de Lucía.

Going modern

The sound of the classical guitar is very much in rock and pop music, too, though practicalities for its use in more ‘electric’ musical environments has necessitated some modifications in its design.

Today’s electro-acoustic nylon-string guitar, as played by the likes of Rodrigo Y Gabriela, solves the major problem of the unamplified instrument: volume. Just like Charlie Christian proved with a Gibson archtop, once the nylon-string could be successfully amplified it could be utilised far more easily in a diverse range of musical genres and styles.

Until the early pioneers of the piezo pickup (such as Baldwin and Ovation in the late 60 and early 70s), the nylon-string remained acoustic - its nylon strings don’t work with a magnetic pickup - and could only be amplified with a microphone into an amp or PA system.

Charlie Byrd, a key figure in the crossover use of the classical guitar in jazz and Latin music begged Ovation’s founder Charlie Kaman to make him a piezo-equipped nylon-string.

“I’m playing in a trio with Barney Kessel and Herb Ellis, and they’re swamping me out. I’ve got to have an electric [nylon-string] on this set. What can we do?” Ovation built him an acoustic-electric Classic.

Nevertheless, it was initially the microphone that allowed influential players’ classical guitars to be heard, for example Brazilian-born Laurindo Ameida with the Stan Kenton Orchestra from 1947.

A South American Byrd

Bill Harris was another classical-playing jazz pioneer in the mid-50s and Charlie Byrd, of course, who’d studied with Segovia in 1954, eschewed his electric guitar to focus on the classical instrument in a jazz setting.

Touring South America in 1961, Byrd heard the different harmonies and rhythms of Brazilian music that featured primarily the nylon-string classical guitar, and in early 1962 recorded Desafinado with saxophonist Stan Getz exposing ‘Latin jazz’ or bossa nova to a huge international audience.

Byrd and Getz’s Jazz Samba (1962), on which Desafinado featured, was a huge-selling record introducing an international audience to Antônio Carlos Jobim (the key composer of the bossa nova movement).

Subsequently bossa nova guitar pioneers such as João Gilberto, via Getz/Gilberto (1964) and its most successful track The Girl From Ipanema - allegedly the second most recorded song in pop history after the Beatles’ Yesterday - achieved global acclaim.

It might be lounge, lift or simply easy listening to many, but the classical guitar in the jazz world was now accepted and numerous greats would use the instrument for recordings and live performance: from Kenny Burrell and Joe Pass to Al Di Meola, Path Metheny, Lee Ritenour and many more.

Heading West

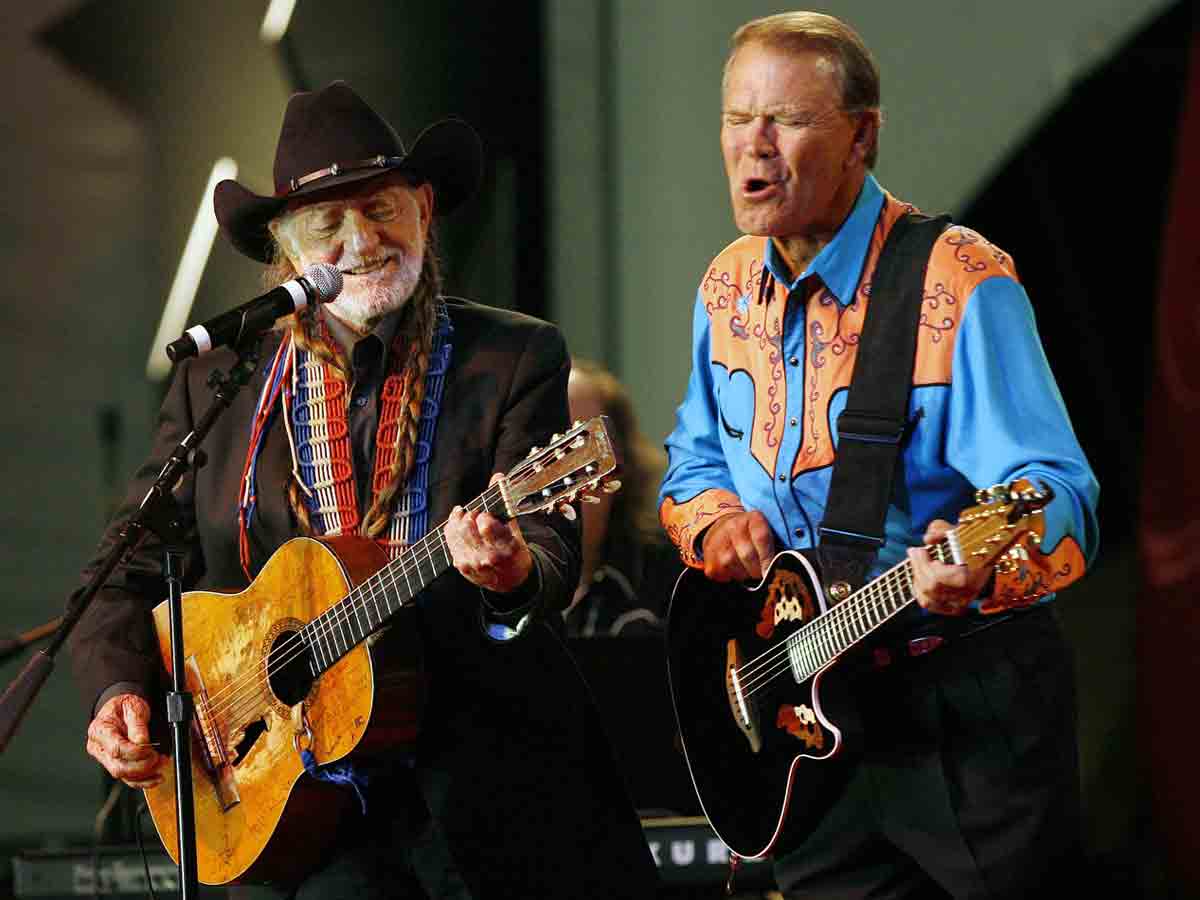

While Brazil has given us numerous great fingerstyle players such as Luiz Bonfá and Baden Powell, let’s not forget country greats including Jerry Reed and Willie Nelson, plying their trade with nylon-strings - a theme that continues today with Taylor-toting players such as Zac Brown.

Chet Atkins has his own part to play in the development of the modern ‘crossover’ nylon- string guitar. He came to Gibson with the prototype for a mainly solidbody nylon-string electric guitar with an ‘acoustic’ sound: the first of its kind.

The Gibson Chet Atkins CE and CEC models debuted in 1982, nylon- string cutaway ‘classical’ guitars with a chambered ‘solid’ bodies and a piezo pickup. The CE had a narrower nut width of 46mm (CE); the CEC was a more classical-like 51mm.

Mark Knopfler’s use of an original CEC during Dire Straits’ mid-80s heyday proved the nylon-string - on tracks such as Private Investigations - could be heard at huge stadium volumes.

In 1989 American luthier Kirk Sands took one of his nylon electric guitars to Nashville for Chet to try; he immediately took the guitar to Gibson and Kirk’s design was added to the CA line of amplified nylon-string guitars and named the Studio Classic.

This thinline, lighter and more hollow electro-cutaway has undoubtedly become the blueprint for the modern nylon-electro guitar, which has been echoed in numerous designs from Ibanez to Godin and plenty more.

Canadian maker Godin remains hugely significant in the modern nylon-electro market, not least popularising synth-access Multiac nylon- and steel-string instruments, arguably taking the nylon-string electro further than any other mainstream maker.

Pop and beyond

Occasionally, the nylon-string has been at the forefront of pop music too: Mason Williams’ Classical Gas was initially released in 1968, and for guitar players of a certain age, whatever their instrument type, it was a rite of passage.

José Feliciano’s spirited Latin-style version of the Doors’ Light My Fire is the definition of a massively successful crossover hit; Eric Clapton’s Tears In Heaven had many a rock and blues player pondering a nylon-strung purchase.

Buenos Aires-born Dominic Miller, in his role as Sting’s guitarist of choice since 1990, has certainly contributed to the cause in mega-selling form on tracks like Fragile and Shape Of My Heart, which he co-wrote.

He’s even managed to impact on the classical charts, in 2004, with his solo album Shapes, a reversal, if you like, of concert classical guitarist John Williams who’s Cavatina (theme from The Deer Hunter), back in 1978, became a Top 20 hit and is still a popular choice for the wedding/function soloist.

More recently, in 2003, José González’s album Veneer spawned the track Heartbeats, which featured in TV, film and most notably a Sony advert.

World domination

Move away a little from the mainstream into the melting pot of ‘world music’ and the nylon-string is pretty much everywhere; from traditional and modern Portuguese fado, to the ubiquitous use in both new and old-style Brazilian samba and bossa nova.

Whether the nylon-string is used to add some albeit often clichéd ‘Latin’ to a pop recording - Madonna’s La Isla Bonita springs to mind - there’s little doubt the modern nylon-string is far more than either a cheap starter guitar or an instrument for just the classical player.

For the numerous guitarists that switch effortlessly to and from steel and nylon instruments, be it Pat Metheny or Antonio Forcione, it’s an instrument that provides another colour: a Les Paul to an ES-175, perhaps.

We’ve just scratched the surface of the nylon-string guitar’s charms in this piece. If you’re new to the idea, or indeed returning to it after many years away, perhaps it’s time to consider what countless players already know: the nylon-string is more than cool... even played with a pick!

Dave Burrluck is one of the world’s most experienced guitar journalists, who started writing back in the '80s for International Musician and Recording World, co-founded The Guitar Magazine and has been the Gear Reviews Editor of Guitarist magazine for the past two decades. Along the way, Dave has been the sole author of The PRS Guitar Book and The Player's Guide to Guitar Maintenance as well as contributing to numerous other books on the electric guitar. Dave is an active gigging and recording musician and still finds time to make, repair and mod guitars, not least for Guitarist’s The Mod Squad.

“Beyond its beauty, the cocobolo contributes to the guitar’s overall projection and sustain”: Cort’s stunning new Gold Series acoustic is a love letter to an exotic tone wood

“Your full-scale companion. Anytime. Anywhere… the perfect companion to your full-size Martin”: Meet the Junior Series, the new small-bodied, travel-friendly acoustic range from Martin

“Beyond its beauty, the cocobolo contributes to the guitar’s overall projection and sustain”: Cort’s stunning new Gold Series acoustic is a love letter to an exotic tone wood

“Your full-scale companion. Anytime. Anywhere… the perfect companion to your full-size Martin”: Meet the Junior Series, the new small-bodied, travel-friendly acoustic range from Martin