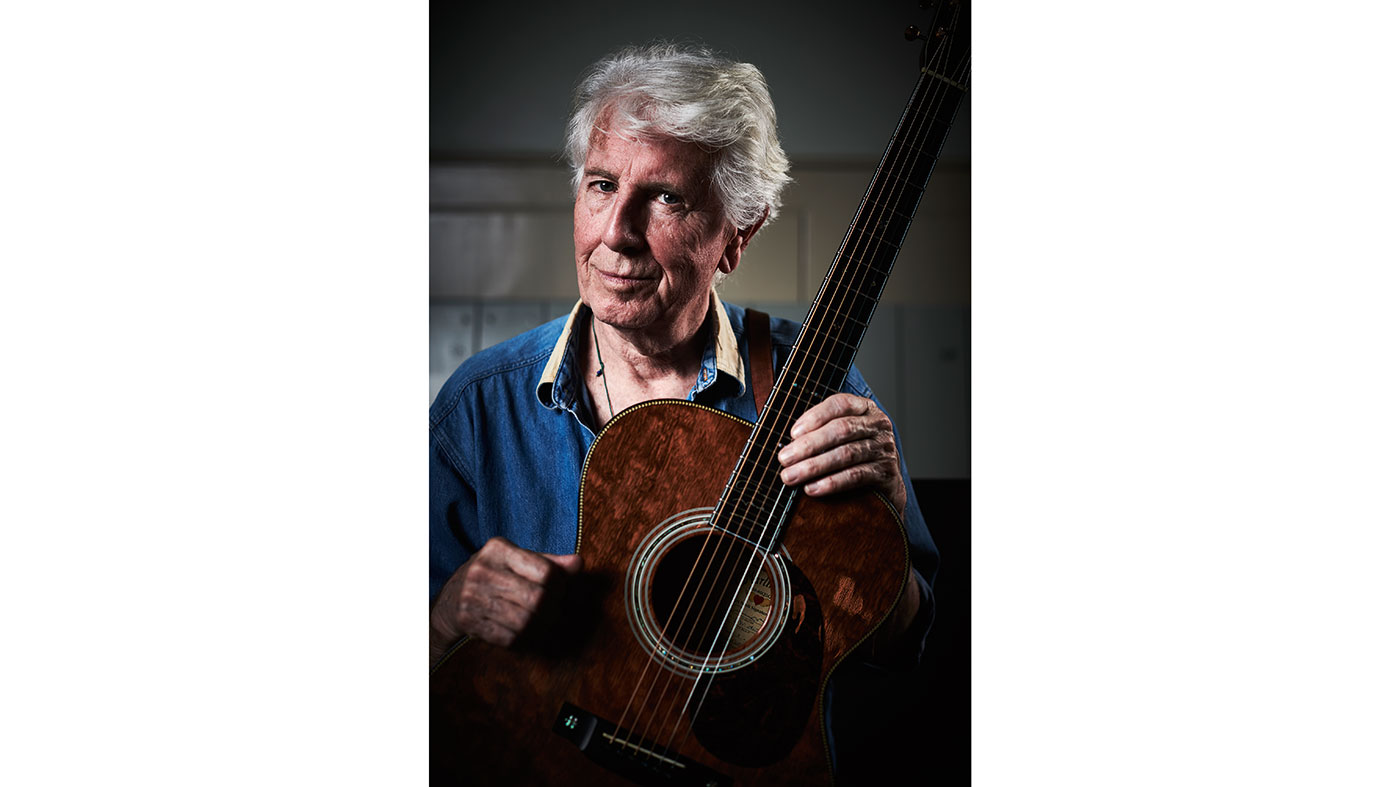

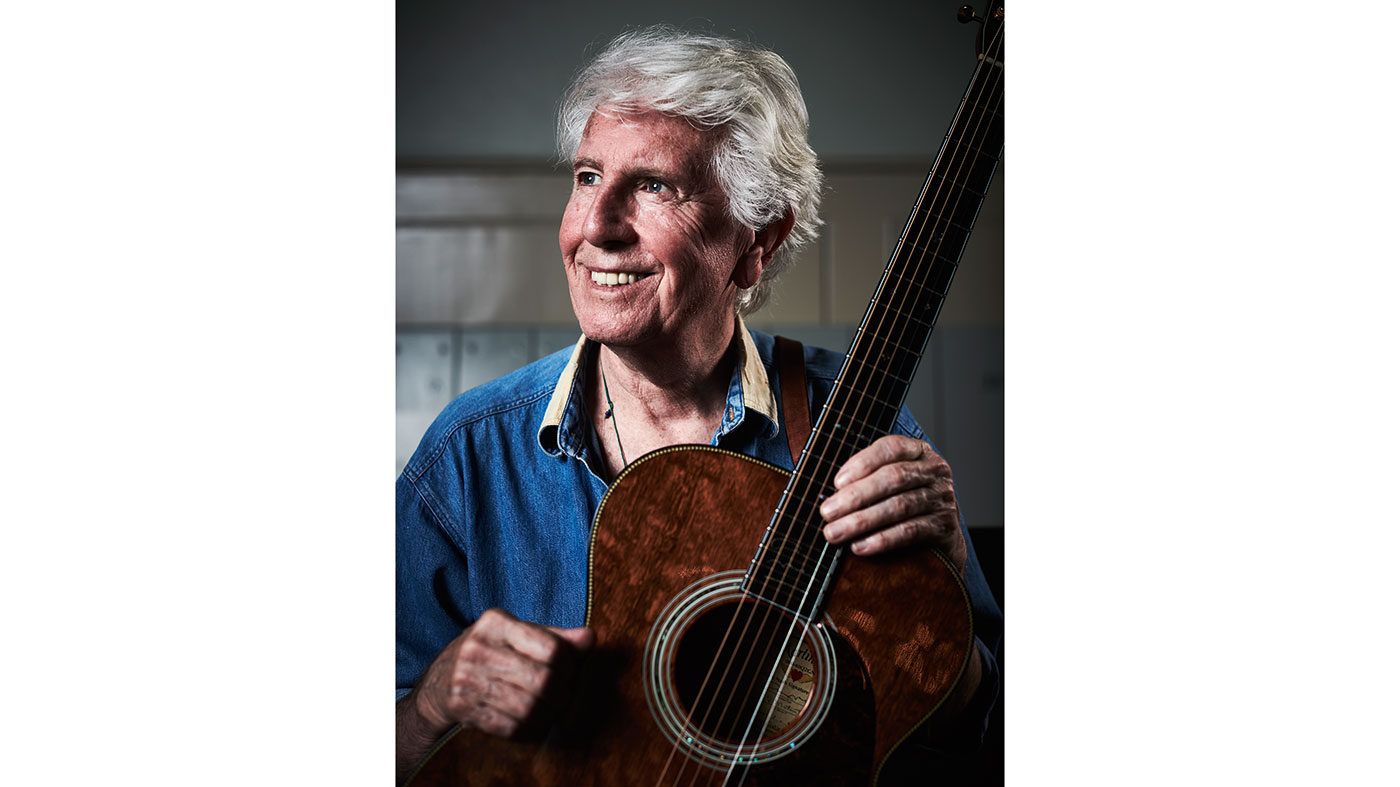

Graham Nash interview: “I’ve written songs every way you could possibly imagine”

The British songwriting legend on Crosby, Stills and Nash, writing and Woodstock

We revisit a 2019 interview with the Crosby, Stills and Nash icon…

Graham Nash, one of the most important songwriters of the '60s, is in town as the star attraction of an Americana-themed season of gigs.

It’s an oddly boomerang-like arc for the Blackpool-born artist, who first rose to fame with 60s hit-makers The Hollies, who were so prolific and successful that their songs spent 231 weeks in the UK singles charts during the 1960s.

Nash’s impeccable ear for radio-ready melody made him the sharpest knife in that band’s creative drawer and he penned some of their biggest hits, including 1967’s Carrie Anne - a sugar-sweet slice of harmony-vocal pop that shows why The Hollies were the era’s true rivals to The Beatles’ crown.

But like many artists maturing in the late-'60s, Nash was drawn west, across the Atlantic, to the kaleidoscopic revolution in pop culture that was happening in California. Joining forces with Stephen Stills and David Crosby, he became one pillar of the most magical vocal and songwriting partnerships in rock history.

From Woodstock to the Marrakesh Express, his has been a dazzling journey across the map of rock music that Nash recounts with the modesty of a pilgrim not the bombast of a conqueror. Now in his seventh decade, he tells us what he’s learned about songwriting, soul-searching and guitar playing along the way.

How are you enjoying the tour at the moment, Graham?

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

“It’s almost over. After six weeks of travelling in different countries and different cities and different bus rides it gets a little crusty. The reason for the tour, of course, is the music and the music has been fine. I’m working with two great musicians, Todd Caldwell on the keyboard and Shane Fontayne on lead guitar.

“We’ve been making music a lot together. Shane and Todd, of course, both being songwriters, they want to support the song, they don’t want to say, ‘Hey, my solo is flashy.’ They support the song and I appreciate that about them both. Shane watches me like a hawk and plays around my phrasing rather than a set pattern - so it’s different every night. I’ve never told him what to play, I just trust that they will support the actual song itself. Shane has always been that way, ever since I first met him.

“Do you know who Marc Cohn is? A songwriter in the United States, he did Walking In Memphis? Right, so David Crosby and I had sung on a couple of Marc’s albums and one day he came to the El Ray, which is a [live music] place in Los Angeles, and he called Crosby and said, ‘Hey, do you want to come down and sing?’ So, we did. Part of his band was Shane.

“At that same time, about a couple of weeks later, Crosby and I were supposed to tour Europe, but our lead guitar player Dean Parks is usually one of the first calls people make when they need a guitar player. But if you spend six weeks out of the country you might lose your place in that hierarchy of calls. Dean didn’t want to do that, so he couldn’t go to Europe, and we asked Shane because we saw how he played with Marc. I think Shane learned maybe 30 songs in two or three days. That’s how we knew straight off he was going to be our lead guitar player.”

Going for a song

How did your relationship with playing guitar begin?

“In a very strange way - somewhere in a pawn shop in Manchester. Let me backtrack a little. For my 14th birthday, I had a choice of either a bicycle or a guitar, and we couldn’t afford a bicycle. The reason I wanted a bicycle was my friend, Fred Moore, had ridden his bicycle all the way to Badenheim in Germany and met Elvis. I thought, ‘Wow, I want a bicycle.’ But we couldn’t afford one. But we could afford a £10 cheap acoustic guitar. That’s how I started my love affair.

“What happened is that in a pawn shop somewhere in Manchester I found a Rickenbacker Steel, with steel plates on the front. Of course, I thought that was what a regular guitar looked like and I tried to play it as a guitar. Of course, after my fingers were bleeding for a fortnight I gave up on that. I’ve always loved that when you play a guitar it is the star - because I wasn’t a songwriter and I wasn’t a singer then, particularly. I’d listened to all the early American rock ’n’ roll; I wanted to be like The Everly Brothers.

“I loved the effect the guitar had on the ladies, for instance. If you were playing at a party and you played a couple of Buddy Holly songs because you knew three chords, all of a sudden you became more interesting to the opposite sex, and I enjoyed that.”

How do you prefer to write? Do you write chord changes you like and then use them as inspiration for lyrics, or does it work the other way around?

Just A Song Before I Go was written on a bet, really. It was the biggest single hit that CSN ever had

“I’ve written songs every single way you could possibly imagine, from it appearing in my mind and me getting it down immediately, like Just A Song Before I Go or Our House, to a song like Cathedral that took me years to write, because when you’re talking about people’s religion you better make sure that every word is as truthful as you can make it.

“I’ve written songs from when I had a studio in my house, a kick drum, then put in a snare drum and then rhythms, and putting a guitar rhythm track on that. I’ve written songs every way you could possibly imagine.”

You touched on Just A Song Before I Go - it’s a beautiful track and a huge hit for Crosby, Stills & Nash. What was the story behind the writing session for that song?

“The origin was this: I was in the Hawaiian Islands and I had a couple of hours to waste before I had to catch a plane back to Los Angeles. I was at the home of a friend of mine, Spider was his name, and as I got up to leave he said, ‘You know what? You’re supposed to be a big-shot songwriter. I bet you can’t write a song.’

“I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘I bet you can’t write a song just before you go home.’ I said, ‘Really? You bet? How much do you bet?’ He said, ‘$500 you can’t write a song just before you leave.’ I still have his $500 because it was written on a bet, really. It was the biggest single hit that CSN ever had, I believe. Like my friend Joe Wall says, ‘If I’d have known it was going to be such a big hit I’d have written a better song.’”

You included Marrakesh Express on your recent retrospective compilation, Over The Years… Given that it was such a hit for Crosby, Stills & Nash, why do you think it was turned down by The Hollies and how did that factor into your departure from The Hollies?

“I’d written a song earlier called King Midas In Reverse. We made a good record of it. It was psychedelic, but we liked it at that time in the summer of love in the '60s… whatever it was - 1966.

“Normally, in The Hollies, we were used to getting in the Top 10 with every single. When I was with them we had, what, 15 Top 10 records? That’s what we were used to. But King Midas only made it into the Top 30 and I think they started to say, ‘Oh well, he’s losing his edge.’ Crosby had heard that song and thought it was a fine song, and in December 1967 I played that last show with The Hollies at the London Palladium for a children’s benefit. Crosby was there and obviously The Hollies had gotten wind of something else happening to me.

“I’d heard me and David and Stephen sing. There was no doubt where I wanted to go; I wanted to follow my heart and follow the sound that we had created. I think that’s why when I played Marrakesh Express they thought it was another hippy-dippy, bullshit song.

“In the tape vault is a recording of The Hollies trying to do Marrakesh Express. To me, it wasn’t great. That song needs the energy of a train through it. I listened to it less than two weeks ago; somebody had found it and put it on the web and, actually, I realised that I was right. It was flat, they weren’t into it - and that was obvious.”

Young town

How did Neil Young’s contribution change the dynamic in the band when he was collaborating with you as CSN&Y?

“I’ve always maintained that Crosby, Stills & Nash, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young are a completely different band. What Neil brought to us was, for want of a better word, darker. I don’t mean darker in a negative sense, but you know what I’m saying? When you look at Neil he brought an edge to it that we didn’t have.

“What had happened is that we created this vocal sound that we loved. All of a sudden, we realised when we finished the record - because The Byrds and The Hollies and Springfield were pretty good harmony bands - that this was something completely unique and we knew it was going to be a hit, or that’s what we felt. That this was not an acoustic album but more acoustic than Led Zeppelin or Jimi at the time. We knew that it was going to be a hit.

I had breakfast with Neil in the Village in New York City and by the end I was convinced he should be in the band

“Stephen played most of the instruments on that first record [Déjà Vu]. He played keyboards, he played B3, he played lead guitar and he played some rhythm guitar, he played bass, he played percussion. We had our drummer, Dallas Taylor, with us, so he didn’t play drums.

“If you think it’s going to be a hit, you obviously think you’ve got to go on the road with this hit, but what do you do when one person out of the three of us played most of the instruments? We obviously needed somebody else.

“Crosby and Stephen were at dinner at Ahmet Ertegun’s house in New York City - the president of Atlantic Records and our dear friend. In the middle of dinner, he says, ‘Hey Stephen, I know who you should get, man.’ Stephen said, ‘Really, Ahmet, who’s that?’ He said, ‘Neil Young,’ and of course Stephen said, ‘Wait a second, I just went through a couple of years of madness with Neil, you want me to go back?’ ‘Yes, man. Neil, that’s who you should get.’

“Because we had created that vocal sound and loved it and it was unique when we made our three voices into one voice, I said, ‘I’ve never met this guy we’re supposed to be inviting into the band. I don’t know if I can be his friend, whether I can tell him secrets or hang out with him. I know he’s a fine writer and a singer because I’ve heard the Buffalo Springfield record,’ so I said, ‘I have to meet Neil Young.’ Obvious, right?

“I had breakfast with Neil in the Village in New York City and by the end I was convinced he should be in the band. Particularly when I said to him, ‘Why the fuck should we invite you into this band?’ And he looked at me and he said, ‘You haven’t heard me and Stephen play guitar together, man?’ And I had, and I went, ‘Okay. You got it.’ He was in the band from that moment on. I do believe that they’re two completely different bands.”

The time they got to Woodstock

Watching the Woodstock performance of you sitting there on the stage and there are all these people, and it’s such an exposed place for an acoustic performance to be… What were your thoughts when you sat down on the stool?

“I think it’s well known that maybe Stephen was a little nervous, because, with all due respect, Woodstock was only the second time that we’d ever played in front of people. That was our second show. The first show was a couple of nights before at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago. We had Joni opening… how ballsy is that?

One acoustic guitar and only two voices to a half a million people, I thought, ‘Wow, man. We took a chance there’

“But it didn’t really bother me. I’ve been in certain situations, certainly not with that many people but with the screaming girls tearing your shirt and grabbing your tie, we’d been through that for six or seven years before I ever met David and Stephen. I was kind of cool with it. But in retrospect, thinking about it, the technology of side monitors wasn’t anything like it is today. It left a lot to be desired. We could hardly hear ourselves, but we knew what we were doing.

“I think there is footage of Marrakesh Express from Woodstock and it’s pretty damn good. I wasn’t particularly scared, but like I said, in retrospect playing Guinevere, which is a lot softer than the Suite, with one acoustic guitar and only two voices to a half a million people, I thought, ‘Wow, man. We took a chance there,’ but we did okay.”

How did you try to fit in with Stills and Crosby, guitar-wise? Or did you regard the guitar more as a songwriting tool than a musical instrument?

“Yes, that’s exactly right. I’m not a great musician at all. I played rhythm guitar enough to be able to write my own songs and play others when the chords are in front of me. I don’t jam - when people say, ‘Hey, come on down to the club and jam,’ I freeze. I’m just not one of those musicians, I never have been.

“But I’m in a band with Crosby who is an incredibly great rhythm guitar player, with Stephen Stills and Neil Young who are two of the finest guitar players in the world, and then there’s me. I have my role in the band and I understand what my role was, but I’m not a great musician.”

Writing up

Looking at the writers that you were close to, such as Joni Mitchell and David Crosby, what lessons did you take away from working alongside them?

“I’ll tell you exactly what lessons I learned. When I was in The Hollies, we had learned to be able to write a melody that you probably couldn’t forget if you heard it a couple of times, Carrie Anne, On A Carousel. But the words left a lot to be desired.

“We were making stuff up, ‘Riding along on a carousel,’ sure, when I was a kid I’d been on a carousel horse, of course, but we made up the words. There were a lot of ‘Moonin- June, screw-me-in-the-back-of-the-car’ kind of lyrics. The melodies were fine. But when I came to America and saw what David, Stephen, Neil and Joni were doing I said, ‘Wow, this songwriting thing is way deeper than I thought.’

When I saw David, Stephen, Neil and Joni, what they were doing, I realised that I just had to step up my game

“The Hollies had written, for want of a better word, a protest song in the mid-60s called Too Many People about the population explosion, but apart from that the lyrics in most Hollies songs were not great. Good pop, but not great.

“When I saw David, Stephen, Neil and Joni, what they were doing, the lyrics they were putting with their beautiful melodies, I realised that I just had to step up my game and that I’d have to start writing about reality, not making words up. I think that writers have to tell the truth as much as is possible and they have to reflect the times in which they live.

“Just as an aside, I’m really very honoured that my music seems to have lasted a long time. But at the same time, it’s amazing how a song like Immigration Man - a song I wrote 40-odd years ago - is still insanely relevant as we are sitting here now. And it’s the same with the song Military Madness and the idea that we can change the world. I realised I would have to step up my game and I am still trying.”

To be truthful as an artist involves opening up oneself and one’s private thoughts to the world. Do you find that a hard thing to get to grips with?

“No, I really don’t. I realised that when I did try and open up the emotional path that I was on… I only write about me. I don’t write for CSN or for CSN&Y, I only write for me. There is a lot of me inside here. That has to come out. I do realise that if you do open up your heart, then you will probably touch people in a deeper way.

“What is happening to me as a failed and flailing human being trying to make my way through this world… the words that I wrote… if they’ve happened to me, then they’ve probably happened to you, too. So, it really could be seen as courage to open up your heart and lay your emotions out for everybody to see. But no, I don’t find it difficult at all.”

Archives

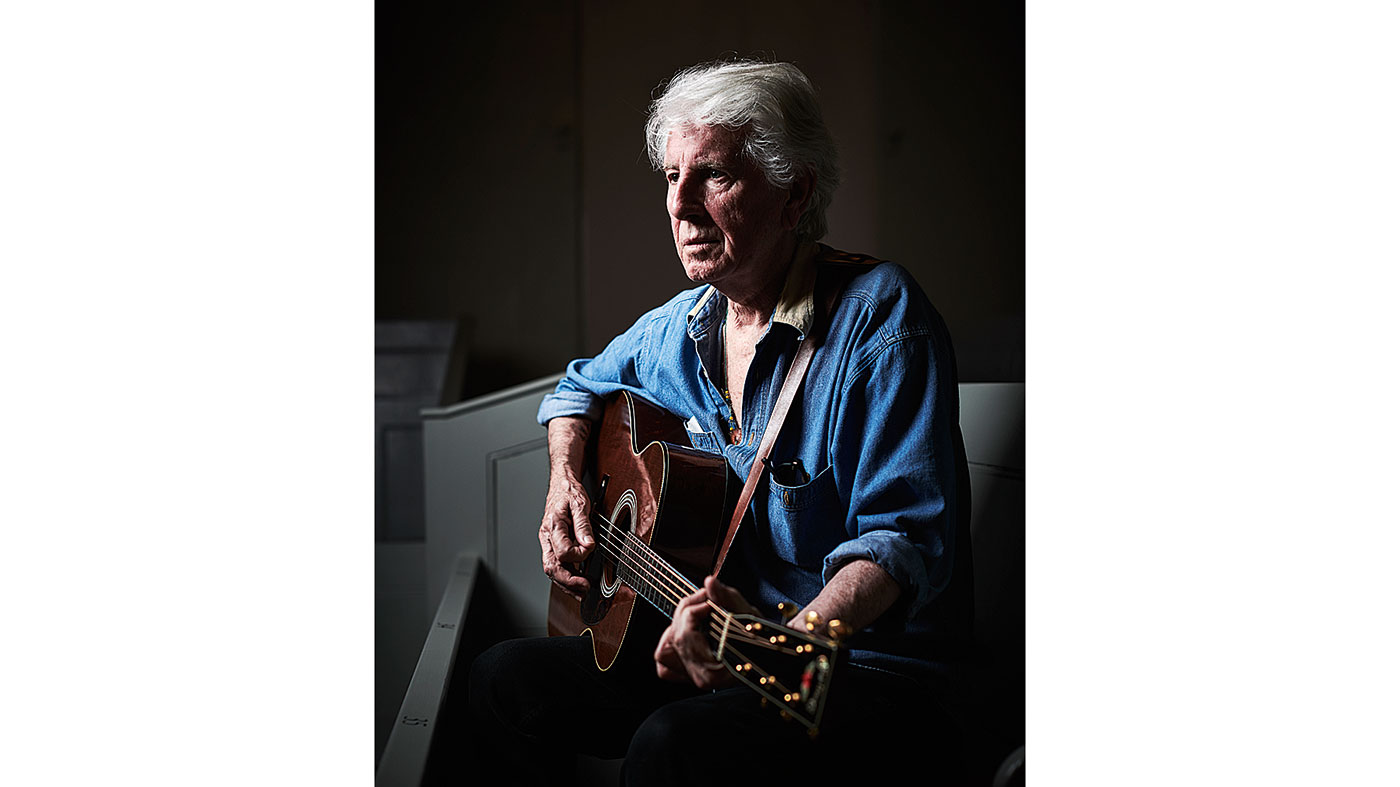

Which guitars have you brought out with you on tour?

“Well, first of all, I’m incredibly proud of the Graham Nash Martin model. My friend Alan Rogan, who has taken care of Pete Townshend for the last 30 to 40 years, and my guitar guy here, John Gonzales, helped design the guitar.

“I have to tell you, Martin did a fantastic job. It’s not some schlock guitar with my name written in mother‑of-pearl all the way down the neck. I’m not one of those people. But I brought a couple of my Martins. I love hand-built guitars. I recently bought three or four from a man in North Carolina called Bob Rigaud. Hand‑built guitars, I love them.

I love hand-built guitars. I recently bought three or four from a man in North Carolina called Bob Rigaud

“There are some songs that I need a bigger dreadnought style guitar on, or I’ve got a Gibson one where I take the bottom E down to D to give it more bass and stuff and a bigger sound. But I’m not a big guitar guy, I like parlour guitars. My Martin is not a big guitar at all.”

What’s next? Will there be more Crosby, Stills & Nash material from the archives?

“About five years ago we had an argument with our record company, Warner Brothers, and it went like this. At one point they said that they owned every single thing that we had recorded.

“I checked the contract very carefully with my lawyer and we told them, ‘Look, the albums that you paid us a fortune for are yours, we understand that. But if I recorded me and David and Stephen in my bathroom and we got a great track and I want to put out, you don’t own that.’ And they said, ‘Yes, we do. We own everything.’ Anyway, we went back and forth. They realised, of course, that they don’t own everything.

“My point is that I’ve been delving into our archives for the last five years. And there is a lot of interesting stuff there to do. What I am going to do now is we only have maybe four shows left on this tour, I’ll go back to America, take a month off. Answer all my emails and my letters and all that silly kind of stuff. Get my studio in better shape and then go back on tour in America on the West Coast.

“And in the meantime, I’ve got many things in my mind that I want to do - one of them being the Déjà Vu record. There were no CDs when we put out Déjà Vu. We had to fade a lot of the stuff because you could only get 20 minutes on the side of a vinyl album, right? But we’d often carry on and keep going for another 12 minutes just jamming, just fabulous. Several songs were like that.

“So, what I’d like to do is remix Déjà Vu from ‘one, two, three,’ from the count off to the drummer putting his sticks on the drums because it’s over. All of it, all 20 minutes, whatever length it was. Because we had to fade them to get them on an album. That is one thing I’m going to be doing.

“Also, me and Crosby have sung with many brilliant artists and we’ve never been paid at all. Not once. But I have been putting a list together in my mind and in my computer… I think there are 25 really very interesting tracks to work on here. From people like Jimmy Webb and Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, Kenny Loggins and Phil Collins - so I’m working on that one, too. It’s a little difficult because David and I are not talking any more, but I still think it’s worth doing.”

Graham Nash’s latest album, Over The Years…, is available now on Rhino.

Jamie Dickson is Editor-in-Chief of Guitarist magazine, Britain's best-selling and longest-running monthly for guitar players. He started his career at the Daily Telegraph in London, where his first assignment was interviewing blue-eyed soul legend Robert Palmer, going on to become a full-time author on music, writing for benchmark references such as 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die and Dorling Kindersley's How To Play Guitar Step By Step. He joined Guitarist in 2011 and since then it has been his privilege to interview everyone from B.B. King to St. Vincent for Guitarist's readers, while sharing insights into scores of historic guitars, from Rory Gallagher's '61 Strat to the first Martin D-28 ever made.