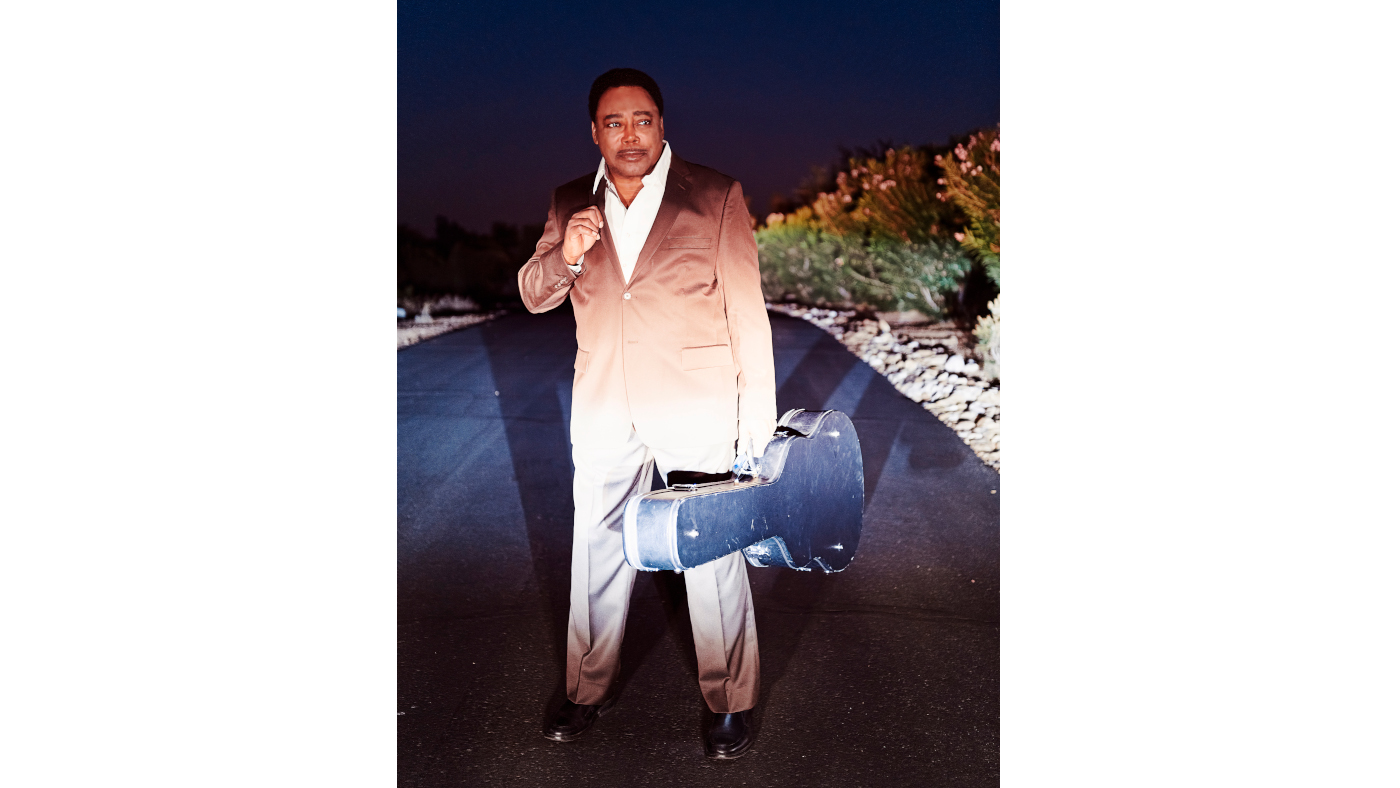

George Benson: “I’ve always been an experimenter. When I was young, I thought I was going to be a scientist”

The jazz legend discusses his famed style, rock ’n’ roll and how it’s all about the audience

It’s been 55 years since the release of George Benson’s explosive debut album, The New Boss Guitar Of George Benson, and this year, the jazz legend released an album dedicated to two of his childhood heroes, Chuck Berry and Fats Domino.

Walking To New Orleans may seem somewhat of a departure for someone known for his jazz prowess and his string of pop hits in the 80s, but as it turns out, it’s just another day at the office for this open-minded and genre-busting legend...

What prompted you to make the new album, Walking To New Orleans - your tribute to Chuck Berry and Fats Domino?

You go to a jazz concert and you don’t really know what you’re going to hear because the jazz guy doesn’t really know what he’s going to play... until he plays it

“When I was coming up, it was the late 50s into the early 60s, and that’s the time period I was most familiar with regarding these two guys. They dominated the radio and jukeboxes at that time. They were both superstars with completely different personalities but equal and as good as each other in what they did.

"They had fans that anybody would envy - not just for sheer numbers, but for the fact that nobody ever said anything bad about them. They were both heroes to us kids at that time.”

What were the differences for you between the rock ’n’ roll stars and jazz musicians around at the time?

“Well, the pop and rock ’n’ roll musicians had a specific commercial audience that they were trying to reach. It’s different for jazz musicians; it’s a lot more open. You go to a jazz concert and you don’t really know what you’re going to hear because the jazz guy doesn’t really know what he’s going to play... until he plays it.

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

"There was a lot about that that interested me. When I heard Charlie Parker play, I learned what an instrument could be capable of, so I reached out for that and, through jazz, I could make that happen. At the time, though, I was attracted to both concepts, which served me well later on.”

Aside from Charlie Parker, what other direct jazz influences did you have?

“There are so many, but Nat King Cole - he was a great jazz improvisor on the piano as well as having an incredible voice. In fact, my last album, Inspiration [2013], is a tribute to Nat Cole.”

Roll over

There are parallels between your career and Nat King Cole’s, in the sense that you were both jazz prodigies who went on to huge commercial success. Was that a conscious career choice?

A lot of the jazz musicians weren’t into rock ’n’ roll, they figured it would pass quickly then go away

“No, because I was already connected with a lot of jazz musicians with the same vision, some famous and some not so famous. However, some of them were die-hards and felt that anything that encroached upon the idea of what jazz was, and should be, was not acceptable to them, so I heard the argument from both sides.

"A lot of the jazz musicians weren’t into rock ’n’ roll, they figured it would pass quickly then go away. I didn’t feel like that. I heard it every day, loved it, and could see it getting more popular every day. I knew rock ’n’ roll wasn’t going away.”

Were you conscious of crossing from one musical world to another? And were you aware that you’d open yourself up to criticism from the jazz community?

“Several of the critics at the time were jazz musicians themselves and were obviously biased towards commercial genres, which is understandable, but once I figured those things out I opened my mind and didn’t insist on my music being one particular way. Because, you know, in life, we can go anywhere and - like life - you gotta be prepared for it.

"I found that my musicianship was the key. If you have good musicianship, you can talk to any genre of music, so I went for that. I found out that the way I could be the best musician was to listen to the best musicians in the world, so I started listening to everybody, especially John Coltrane, Wes Montgomery, Grant Green, Hank Garland and many, many others.

"All I wanted to hear was good musicianship. I can’t define what it is about cats like that, but you know it when you hear it. That was an incredible lesson for me, because it taught me to trust my ears and nothing else; it wasn’t about whether it was jazz or not.”

It’s interesting to hear how you play and sing on the new album. It sounds like trademark George Benson despite the rock ’n’ roll backing...

“Well, I found something out when I was with CTI Records, just before the Breezin’ period [1976]. I was working with people that were jazz musicians but had a commercial ear: Stanley Turrentine, Hubert Laws, Pee Wee Ellis and people like that. I learned that the improvisational skills I’d picked up in the jazz world worked with any kind of music. It could be a blues, a ballad or R&B - the way I played worked with all of that, so I am very comfortable playing things that aren’t necessarily jazz. I even did some things with Chet Atkins and he loved my playing and I loved his - it worked together.”

Audience interaction

When you released New Boss Guitar in 1964, there were a lot of great guitarists around such as Wes Montgomery, Grant Green, Kenny Burrell and Joe Pass. Were you all aware of what each other was doing, musically?

“Of course, but I was slightly behind those guys - they were a little older than me [laughs]! But I was learning from them, because they had ‘the secret’. They had what it took, because once you heard them, you couldn’t forget them and that’s the way I wanted to be.

"I used to hang out with Tal Farlow and, man, it was like going to an incredible school that I couldn’t afford to go to otherwise. I got all I could get from him. But just being around those guys was special. It was a culture thing, too, big time. If I was playing around New York, I would go to the clubs where they were playing and soak up all of that incredible stuff. That was another school for me - that’s how I learned to play.”

Would you consider yourself a self-taught musician, then?

The main thing is the audience. Ain’t much point playing if you ain’t got no audience!

“Yes, basically I am. My father started me off with the first few chords and I quickly got into listening and just trying things out. I’ve always been an experimenter. When I was young, I thought I was going to be a scientist, but I guess the closest I got to that was to be a musical scientist.

"I listened to Wes and thought, ‘What would it sound like if he’d added this note in?’ and I tried it and it started to work for me. For about seven years I worked on that particular formula - listening and trying. I didn’t get really comfortable until one day, on a recording session, it felt like a moment to try some of these things and the producer and the band all went, ‘Wow!’ and I thought, ‘This is going to mean something to my career if I trust my ears and do my own thing.’

"There were two or three things I started doing that turned out to be very beneficial, such as developing Wes’s octave technique to incorporate a note between the octave, and learning to sing while I was playing.”

After your stint at CTI you developed a more commercially viable sound in the mid-to-late 70s with albums such as Breezin’ and In Flight. Did you feel you were compromising in any way?

“Well, maybe compromising, but for the better, because the main thing is the audience. Ain’t much point playing if you ain’t got no audience! You need people to be listening and to get them to listen, you need to speak in a language that they know.

"People would come to me in the clubs and say, ‘There ain’t enough blues for me,’ or ‘There ain’t enough rhythm for me,’ so I started adding these things like ingredients in a recipe. Just a little here and there to make people feel comfortable when I played and then they knew that you were there for them. I mean, I could play - I knew that. And I had confidence that I could play, but I had to let them know that I was playing for them.”

Make it talk

How about the singing? You seem to have as much commitment to that and get as much musical satisfaction from it as when you play the guitar...

“Most definitely, although it’s a little more effort for me to sing. My singing career came later - I was almost an old man by then! Now, I had been singing since I was a little boy, but in my mid-30s when I started using my voice seriously, I found myself competing with, basically, youngsters on the pop scene. These were people in their teens and early 20s, and that was in addition to all the established stars, so that was a tough one for me.

The guitar can do things the voice cannot do and vice versa

“If I was to compete not only with the likes of Nat Cole but with all the great young singers making records at that time, I had to pay a lot of attention to my vocals. You know, whether my phrasing was right and stuff like that.

"You can’t be bothered by asking yourself those questions while you’re performing. You have to ask yourself that stuff before you go on stage. Then you have to learn how to present it.”

One of your trademarks is to sing in unison with your guitar. Are you singing what you play, playing what you sing, or a combination of both?

“[Laughs.] It depends on which one is sticking out. It’s tough, because the guitar can do things the voice cannot do and vice versa. The guitar can play very fast or tight phrases or very wide phrases, but the voice is more driven by melody, so they are both dependent on each other. I realised that I was humming the guitar lines anyway, so I thought, ‘Let’s see what happens if I sing out when I’m playing.’”

How is your guitar playing affected by your voice when it’s in tandem?

“I would say it’s more conversational, because there are things that I can play on the guitar that my voice can’t do. I have to leave some stuff out. In other words, it’s more melodic.”

How about your signature Ibanez guitar? How did your relationship with Ibanez come about?

“I first tried the new wave of Japanese guitars when they started to appear in the 70s. A lot of guitar players turned their noses up at them [at the time], but they were incredible. For a start, they didn’t break. With all my other guitars, I’d have to go into the store at least once a week while I was on the road to have them taken care of; they were always falling apart.

"So after a while, Ibanez came to me and said they’d be interested in having me as one of their representatives. I told them what I needed from a guitar and they came up with the first two guitars for me - the GB10 and the GB20 - and I’m proud to say that guitar has now been in production for about 42 years. I still have the originals. It’s a great road guitar; I don’t have to worry about it breaking up on me. Of course, that’s very, very important to me.

"I do use the new models, which, in a way, are better because they’re more refined now, but there’s not much difference between that and the original guitar.”

George Benson’s latest album, Walking To New Orleans, is available now on Provogue.