Gavin Rossdale talks us through Bush's platinum hits: "These songs were not written with a view to any degree of success… I had toiled for many years and nothing had worked"

From unemployment in London to 20-million album sales and US stardom, the songwriter recalls a remarkable rise – "I was pretty rubbish at first, but I had a knack"

Hailing from London in the early-to-mid-'90s, Bush first hit the scene when Britpop was well on its way to becoming the dominant guitar-based genre of the decade. Meanwhile, on the other side of the pond, grunge had gone mainstream and was enjoying/writhing in the discomfort of unprecedented levels of commercial success.

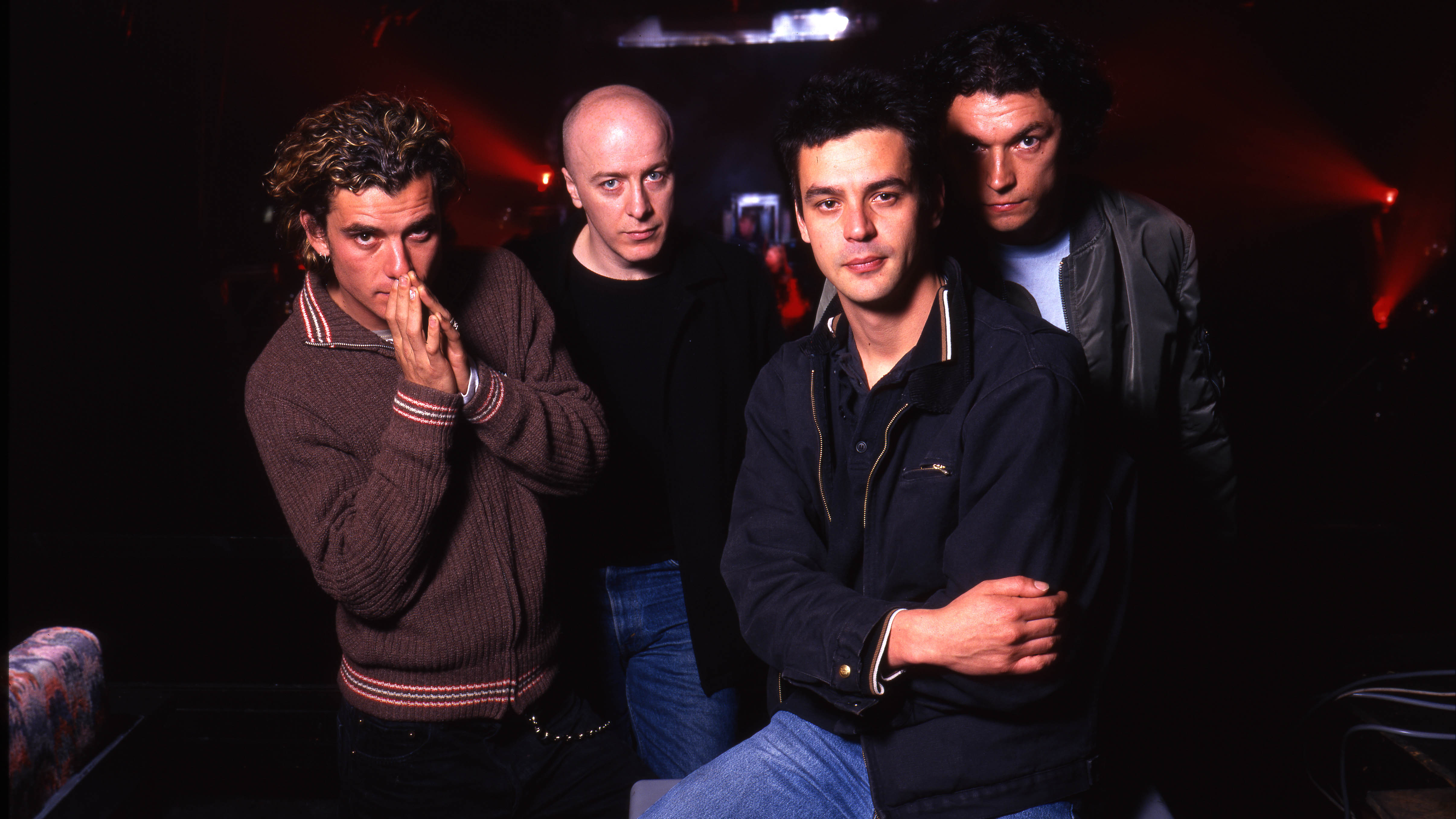

With their in-your-face fuzz riffs and self-described “angry young man” of a frontman in Gavin Rossdale, Bush connected much more instantly stateside than they did on home soil, and their 1994 debut ascended to 6x multi-platinum levels of success within three short years of its US release.

Now, as the 30th anniversary of debut Sixteen Stone approaches, the band gives us Loaded: The Greatest Hits 1994-2023. Stacked with stand-out tracks from each of their nine studio albums as well as Mouth (The Stingray Mix) from the 1997 remix album Deconstructed, a relatively obscure cover of the Beatles’ Come Together from 2012, and the group’s latest single Nowhere To Go But Everywhere, it delivers a panoramic view of a band that has always refused to settle into a stylistic rut.

Discussing how he keeps the musical creativity fresh, Rossdale – also a keen chef – boils it down for us with a tasty culinary metaphor. “For me, it’s just about being interesting all the time,” he explains. “It's like a bite of something spicy and hot and then a simple something that mellows you out and then goes to another different texture. To me, it’s about how you stop people getting bored.”

Subtle sonic reinventions, governed by Rossdale’s evolving musical tastes, permeate and distinguish each of the first four records: 1994’s Sixteen Stone, 1996’s Razorblade Suitcase, 1999’s The Science of Things and 2001’s Golden State. But it was the band’s break-up in 2002, followed by its subsequent reformation with a refreshed line-up almost a decade later, that provided the most seismic shift in Bush’s sound. Most notably, original lead guitarist Nigel Pulsford departed and was replaced by post-hardcore specialist Chris Traynor.

Now, commonly residing down in the depths of Drop-C tuning, Bush forge ahead heavier than ever, embracing modern tones and a contemporary production edge. Speaking from his Los Angeles home, Gavin Rossdale looks back at a handful of cornerstone tracks from the last three decades…

Everything Zen – Sixteen Stone (1994)

‘Everything Zen’ is the track that kicks off Loaded and it kicked off your career too, especially in terms of getting you noticed in the US. What kinds of recollections do you have about that time and the excitement surrounding this particular song?

Get the MusicRadar Newsletter

Want all the hottest music and gear news, reviews, deals, features and more, direct to your inbox? Sign up here.

When I wrote that song, I was pretty unemployed

"For me, writing songs - still, even up to yesterday - are ways for me to apply my self-learning and to learn music. So, there’s something about Zen. When I wrote that song, I was pretty unemployed. I was trying to get a record deal. Britpop was really massive and I was just trying to break into the pub circuit in Camden. I wrote that song and I felt this weird frustration while everyone was fawning over Britpop. I was going this anti-commercial route, making rock music for the Mean Fiddler or for Dingwalls or wherever else we would play back in London.

"I was just ranting in that song and there are so many references in there - like to the David Bowie interview on how much he loved Suede. I was just being jealous. ‘Sex Is Violent’ was the Jane’s Addiction line. I didn’t agree with that so I wrote, ‘There’s no sex in your violence.’ Then there’s the Elvis thing. I was just a sort of angry young man making rock music in my bedroom.

The record got rejected by the distributor. We made the record and then we lost the distribution deal, so I went back to work. I was just painting some offices near Selfridges in London. They called me up and said, ‘Everything Zen has been picked up by KROQ-FM. They’ve fallen in love with it.’ I didn’t know what KROQ was and I didn’t know what that meant. Then, when I went on tour and played CBGB in ‘95, that was the first song where people would know it at my shows.

"Everyone looked cooler than the next person: there were biker dudes and tattooed chicks and everything was happening. Everyone seemed like they were part of the scene. So, walking out into a sold out crowd at CBGB, was when I realised my life had a different, new sense of momentum.

What guitars were you using around that time?

"I only had one guitar and that was my purple Jazzmaster that I got for £900 from Vintage & Rare in West London. I played it through a Vox AC30 with some pedals. It didn’t sound as good in the studio. In the shop, it sounded better with their Marshall cabs. It was Joe Walsh’s guitar and, when I got it back to the studio, my band didn’t believe that. So, I just used that. It’s just over there, about five feet away from me."

Glycerine – Sixteen Stone (1994)

Glycerine, from that same album had quite a different sound - a lot sparser and raw in a different way. Do you recall what your influences or inspirations were for that track?

"I mainly remember writing that song in maybe one or two goes and mainly being struck by the fear that I had nicked somebody else’s song! Again, I’ve got to tell you that these songs were not written with a view to any degree of success. I had toiled for many years and nothing had worked, so there was no guarantee. Even more ignorantly, there was no concept of the potential of the song.

I was pretty rubbish at first, but I had a knack

"It’s really good to be 18 or 19 because you’re so dumb, but you’re just so sure that you’re not. I didn’t know anything, but I didn't want to be told anything, so I just forced my way through. I was pretty rubbish at first, but I had a knack. I don’t know, maybe it was all the reluctant years going to f**cking church every morning for school before assembly, where you’d just sing hymns. You’d feel terrible the night before, but you’d hear all these hymns and these natural cadences. I really think that’s the only place I would’ve heard that, and is why I have any sense of melody.

"Jerusalem was probably a bigger influence than the band Television! It’s just in there, in my DNA.

"So, I wrote that song and just couldn’t believe that I’d worked my way to that song falling out of me. It felt like a sense of accomplishment, just the quality of my writing. It was nothing to do with deals, success, units, sales - any of that - it was just like, ‘Okay, that doesn’t sound terrible. It sounds legitimate!’ So that way my sense of excitement about that song."

Greedy Fly – Razorblade Suitcase (1996)

Bush then got very big, very quickly. The next album, Razorblade Suitcase is one that you’ve previously compared to The Beatles’ Help, in the sense that you were learning to deal with that rapid success…

You go from nobody giving a shit and every door being bolted shut, to people pretending to give a shit, and every door opens

"You get swallowed up by it. People have said a thousand times that there’s no training for being a real rock star. There’s no training for it. You go from nobody giving a shit and every door being bolted shut, to people pretending to give a shit, and every door opens. So, you can go many different ways. Some people let it go to their heads and become really arrogant and annoying. I really felt that there had been so many years of struggle that I finally felt that I could just be myself in my work.

"So, I felt a sense of relief that the doors were finally open. But you’re essentially getting swallowed, no pun intended. With Greedy Fly, I had that."

"It’s funny, I did a podcast the other day with Corey Taylor from Slipknot and Bert Kreischer. Bert goes to us both, ‘What song do you wish you’d written?’ and Corey goes, Greedy Fly. I hadn’t been playing it on tour for a couple of years. I’d just rested it for a bit. The next night, I was like, ‘F**k! We’ve got to play ‘Greedy Fly’!’ If it’s good enough for Corey and he wanted to write that song, I’m missing something. I really enjoyed playing it.

"I was just getting tired of playing it because I felt that it did too much sitting back in the verse and then going for the chorus and that thing it did. So, I’d felt more connected to some of the more recent things I’d written. But because he loved that song, I began to play it again."

What was it like working with Steve Albini on that record?

We’d really become such a layered band and more interesting than I felt we were given credit for

"Brilliant! The decision behind it was that I loved a PJ Harvey record [1993's Rid Of Me]. We’d been on the road for three years. We’d been accused of so many things and the idea of being this ‘instant’ band because we’d had ‘instant success’ after many years of struggle, of course. But, it felt like we’d really become such a layered band and more interesting than I felt we were given credit for.

"So, I thought with Steve, he’d just record you as you are. There’s no artifice with him. He bases his life off of literally no suspension, no artifice. He’s not a comfortable chair in any shape or form! Therefore, if you record with him - and he’d done The Breeders, The Jesus Lizard, Fugazi - he just got those bands and got them intrinsically. That’s what those bands sounded like."

In some ways, it was the worst decision to make, having been so unfavourably connected to Nirvana

"In some ways, it was the worst decision to make, having been so unfavourably connected to 2. It seemed such a suicidal move to not placate people, but just incense people. But I thought in a funny, weird, perverse way, it would actually illuminate the differences because, again, it takes away all the artifice. If Albini had a trick that he’d always give to me, The Jesus Lizard, Nirvana and PJ Harvey, you’d hear it. But, he didn’t have that.

"Well, he does actually. It’s his drum sound and his specific approach to drum recording is his sound. I just was so in love with that.

"I think, where it could have been a better record is that it was a bit baggy. The number of times I’ve wished I could edit those songs and just make them a bit more tight. Steve was always very hands-off about it. He’s a really good friend of mine, so I love him, but I probably would have been in a bigger band if I had done the record again with Clive Langer and gone for something more like Sixteen Stone.

"Sometimes I think about that in my life, and still, I chose a much more difficult route and then kept on changing."

Letting The Cables Sleep – The Science Of Things (1999)

On the subject of changing sounds, The Science Of Things saw you broadening your sonic scope and tapping into some different guitar tones and a different production feel. What was the aim with that record and, in particular, the song Letting The Cables Sleep?

It was the height of Britpop, everyone was really proud about England

"I had done the very visceral, raw Steve AlbinI no-overdubs-record. It was very bare bones. I lived in London opposite the pub where it was Primal Scream and Blur and Mayfair Studios and Oasis – everyone who was in that Primrose Hill lot. It was a very fun time. It was the height of Britpop, everyone was really proud about England – Liam and Patsy were on the cover of Vanity Fair and the British were taking over.

"I was like, ‘Why have I got to make these raucous rock records? I want to bring in a little bit of programming and something a bit more modern.’ It’s what I grew up with. I was friends with Tricky and Massive Attack, so I just wanted to do some programming. I tried to make this hybrid with my London influences. So, I did half the record traditionally with Clive Langer. Then, the other half, I did with Tom Elmhirst, who became a really successful mixer. He’s like a 14-time Grammy winner with Adele and that whole lot. He’s one of my best mates that I grew up with and he did Letting The Cables Sleep.

"I just wanted to do something along the lines of being more trippy, more London, more late night. I wasn’t just about being in a raucous rock band. I liked other things too."

"I wrote this song for a friend of mine who was HIV positive. That was at a time when the stigma was still pretty horrific. Any mention of it would mean that he wouldn’t work anymore and he battled for a couple of years with it and then ended up actually shooting himself. At that time, it was a death sentence. It was just really sad. A very, very, very painful song and an interesting, kind of weird arrangement.

"There was a Nightmares On Wax version of it that was really good. People love that. I love that and I might do it on the tour coming up because we haven’t played it for a while. Whenever we do, people really connect to it."

What would be a deep cut that’s not on Loaded that you’d recommend people go and check out to get to know the band even better?

‘English Fire’ [from 1999’s The Science of Things]. It’s one of my favourite songs and I need to play it again. So, the more people that hear it, the more chance I get that it’ll be requested at shows.

The People That We Love – Golden State (2001)

You then went back to your roots a bit on 2001’s Golden State, with lots of abrasive riffs and aggressive guitar on songs like The People That We Love.

"I actually thought about it yesterday because I wrote that song originally about the Magdalene homes. That’s the lyrical beginning of it. I was reading about the homes and what they were doing with children born out of wedlock in Ireland in the ‘70s. It was horrific. I don’t know what happened. But my sister had gone on a trip to Bali, so suddenly I got this whole new thing about my sister being away and I don’t know how that stayed in the song. Nowadays, I’m really uptight about editing and wouldn’t have let it go that far.

That song didn’t have the success it deserved melodically and musically because I failed to make the lyric as strong as I had on other songs

"It’s a weird song because it’s the one song that sticks out like a sore thumb that pokes me in the eye because I didn’t get that lyric as clear and as good as the rest. That song didn’t have the success it deserved melodically and musically because I failed to make the lyric as strong as I had on other songs. It’s like a stone in my shoe, that song!

"It’s funny, with every single other song I have, I can get lost in it. But, when sing that song, I’m always like, ‘Where’s the f**king Magdalene homes?’ I’m always really distressed by that song."

At this point, Nigel Pulsford moved on and Golden State was the last record you did with the original line-up. Do you guys stay in touch and is there anything you miss about his guitar playing?

"No, he checked out of life and checked into being a dad, which was admirable in some ways because I’m also a dad, but I wasn’t when he made that decision, so I didn’t quite relate. But he’s a fantastic guitar player. A wonderful guitar player and he had an amazing, intrinsic, brilliant, genius choice of notes. He would always find the right notes to play.

"Funnily enough, he’s a very different guitar player to Chris [Traynor] because Chris is actually more angular and much more measured. Chris’s forte is finding notes and finding parts – he has a savant way with parts. He’s an incredible architect, but a different player. Nigel would just play over the stuff and improvise. Chris doesn’t improvise as much, so there’s different qualities. Both amazing, but in different ways."

More Than Machines – The Art Of Survival (2022)

The current line-up has perhaps steered the band into heavier territories, making use of drop tunings and big, hooky riffs. What do you think a newer song like More Than Machines says about Bush in its current form?

I don’t write anything in standard anymore

"I got really into that as I sort of experiment and learn on the voyage of music. I’m in a world of detuned guitars. I don’t write anything in standard anymore. I haven’t written a song in standard for about five years. So, that’s just allowed me a different world to inhabit, a different jungle to navigate.

"This [song] is Chris. It’s actually Chris’s riff and it’s just really exciting. I like that. My aesthetic is finding melodies on top of progressive riffs, progressive music and it’s always detuned - always in a darker, weirder forest than I’ve ever been before.

"It was the last song I wrote for the last record and the Roe vs Wade judgement had just gone through here, which, being an Englishman in America, was really hard. Obviously, I’m from London, so it’s incredibly progressively minded, very open and very inclusive. So, an archaic concept of having control over womens’ bodies is just an abhorrent idea. I was annoyed at myself that I hadn’t referenced it in the songs. I thought: ‘What kind of social commentary is that? To sit in silence, you’re complicit, you’re a piece of sh*t, you’ve got to say something!’

"‘Girls, you’re in control / Not the government’ is one of my best lines. Then there’s reference to climate change in there and I just think that if you can not try and lead – you know, I can’t bring solutions – but I think that in music, it’s really good to have the zeitgeist in there and have what’s going on in there.

- Bush – Loaded: The Greatest Hits 1994-2023 is released on 10 November via Round Hill Records / Universal Music Group. More info at bushofficial.com

Ellie started dabbling with guitars around the age of seven, then started writing about them roughly two decades later. She has a particular fascination with alternate tunings, is forever hunting for the perfect slide for the smaller-handed guitarist, and derives a sadistic pleasure from bothering her drummer mates with a preference for “f**king wonky” time signatures.

As well as freelancing for MusicRadar, Total Guitar and GuitarWorld.com, she’s an events marketing pro and one of the Directors of a community-owned venue in Bath, UK.

"No one phoned me. They never contacted me and I thought, 'Well, I'm not going to bother contacting them either'": Ex-Judas Priest drummer Les Binks has died aged 73

"At first the tension was unbelievable. Johnny was really cold, Dee Dee was OK but Joey was a sweetheart": The story of the Ramones' recording of Baby I Love You